During the early days of the pandemic, Liz Johnson Artur was left to face her immediate surroundings. Luckily, that approach is a core part of her practice, which has evolved over a nearly four-decade career interwoven with photojournalistic work and editorial photography. This might help to explain why, when the racial uprising erupted during the summer of 2020, she was eager to step into the streets of Peckham — her home of 25 years — to both join the protests and record history unfolding in real-time. That impulse resulted in a new book from Tate, titled Time Don’t Run Here. It’s part of the museum’s “Tate Photography Series”, which will highlight four photographers each year threaded by a common theme. This year, that theme is “community and solidarity.”

Raised between Bulgaria, Germany and Russia, Liz took a trip to Brooklyn in 1985 that prompted an exposure to Black culture that she’d yet to experience growing up. She has said that the camera she carried during her stay provided a way of understanding who and what she saw, setting her on a path of religiously documenting Black life in all its shapes and complexities throughout her life. Beginning in 1991, she began assembling her photographs into a collection she named the Black Balloon Archive, using her eye to center and uplift Black perspectives, experiences and communities spanning the African diaspora for over thirty years. From her studio over video chat, Liz explains that Time Don’t Run Here is an extension of this archival work.

We spoke to the artist last week ahead of the book’s launch about activism, the physicality of her images and the joy of shaping narratives.

How did the collaboration with Tate come about, and how did you decide on the theme of this new book?

It was in this funny time that we all lived in — I think it was around the beginning of corona. They came for a studio visit. I thought it would be nice to give them something that is also accessible to people. That’s what my work is about.

Then what happened was the Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

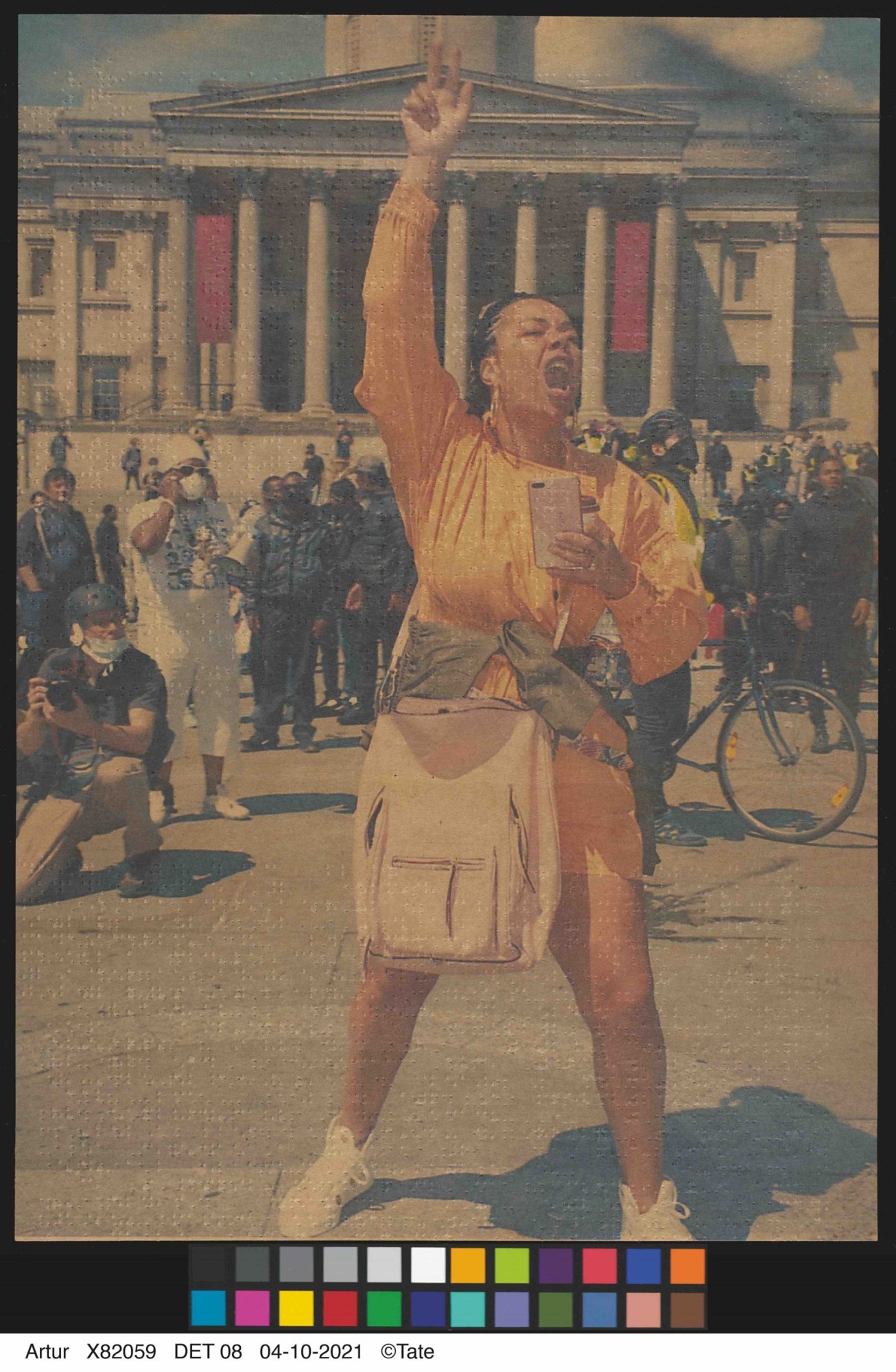

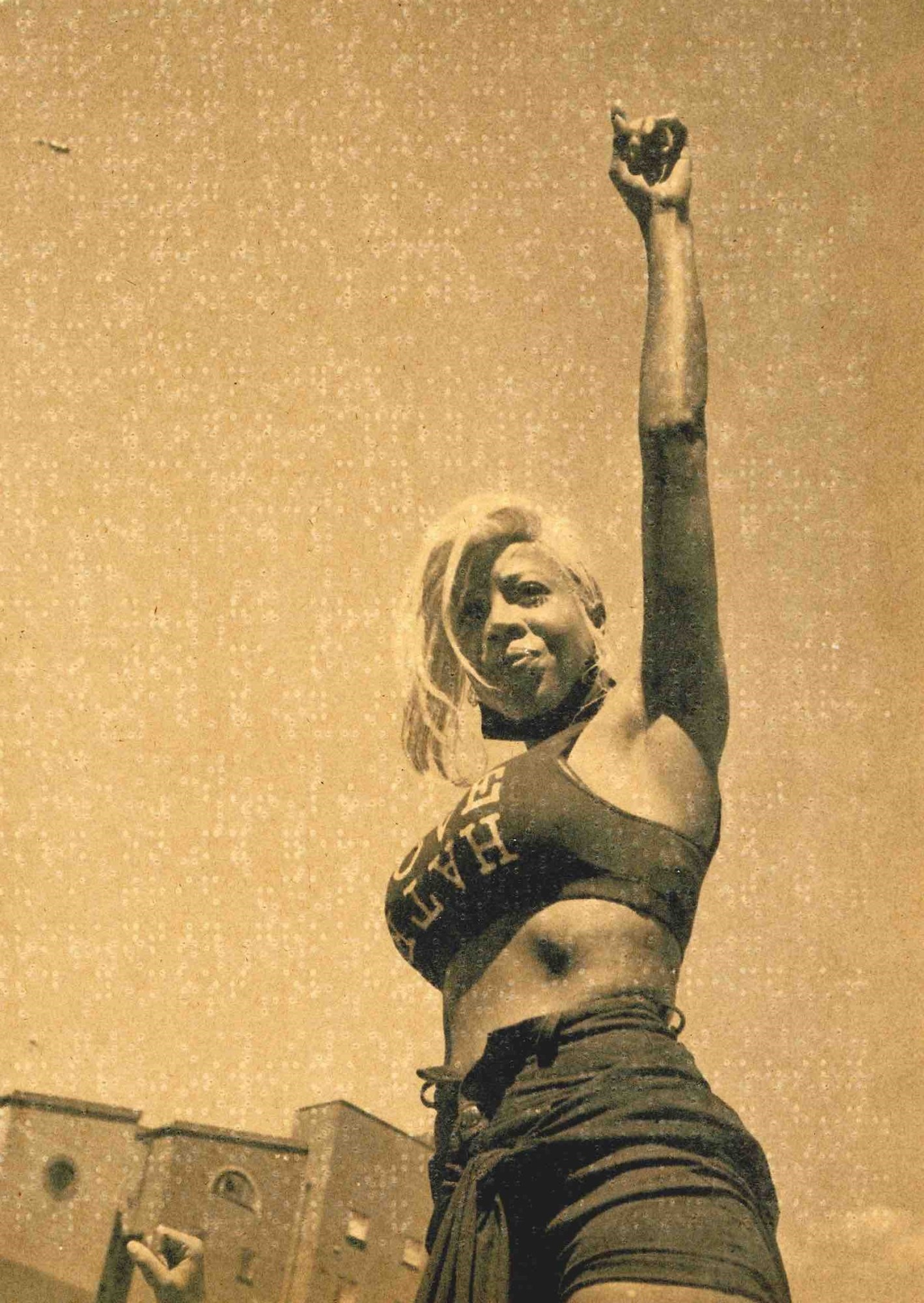

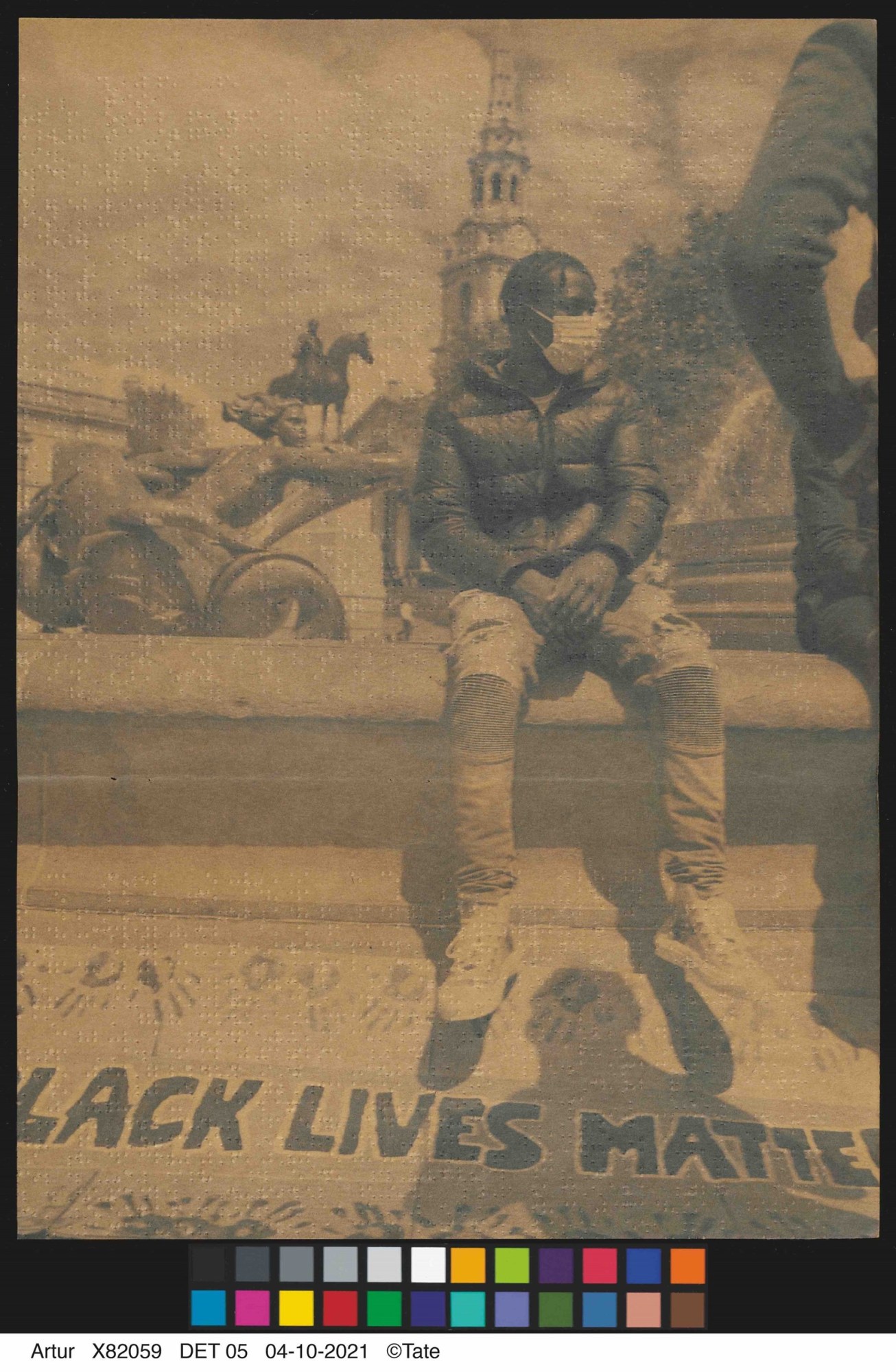

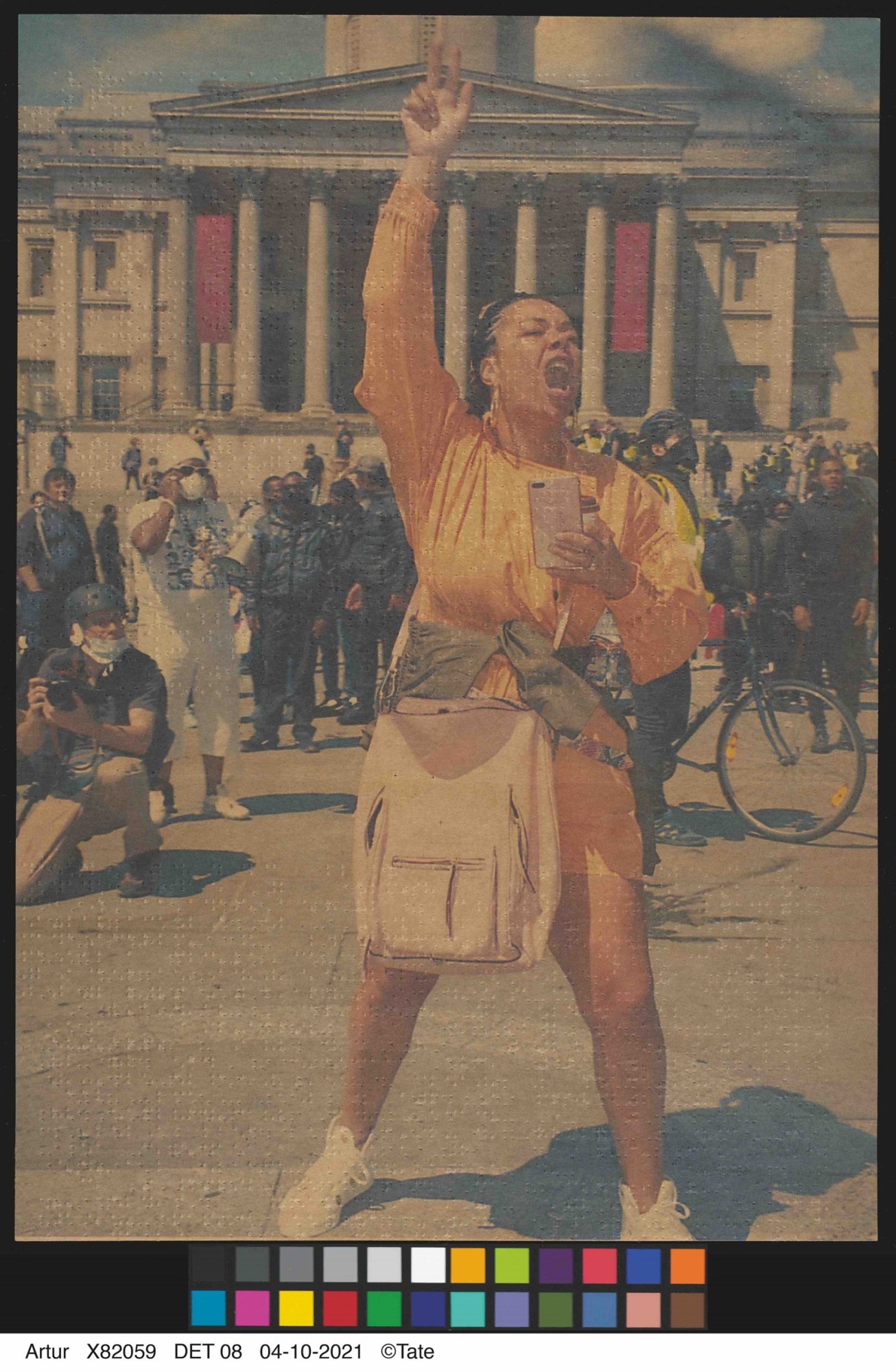

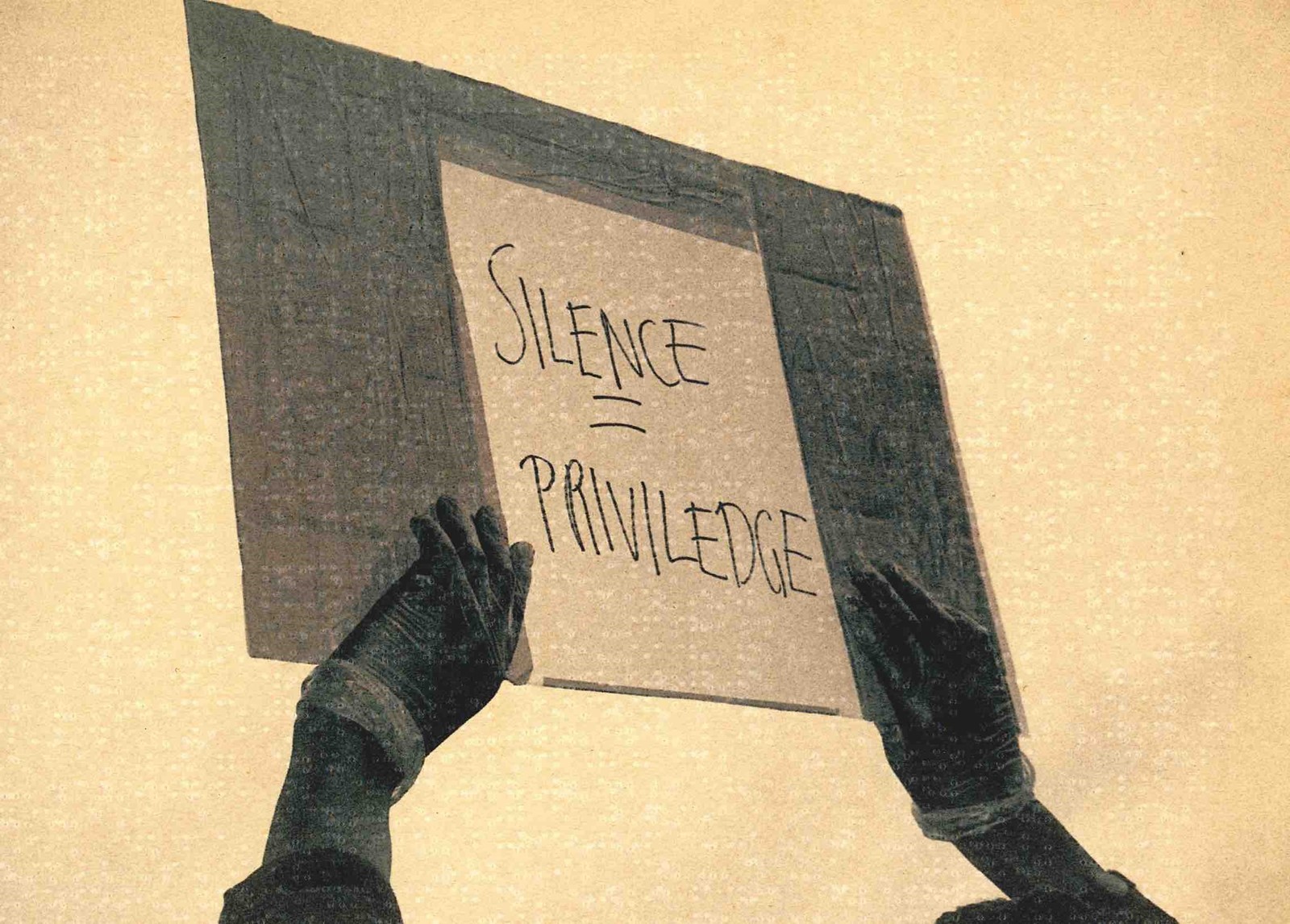

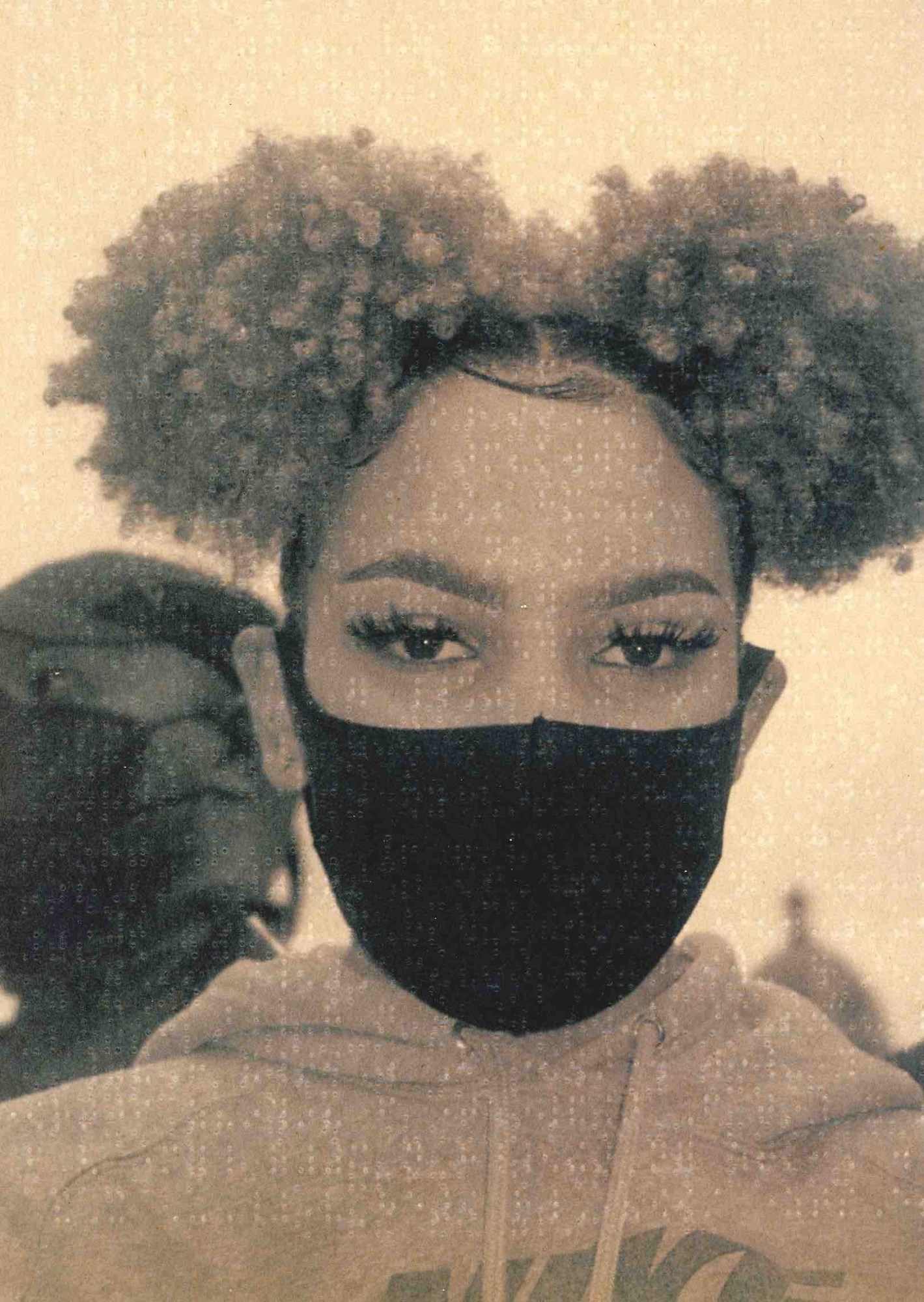

I went to these marches simply on my own. It wasn’t just young Black people — there was a kind of presence that I haven’t seen. It felt quite special, and my first reaction to things that I encounter is to take pictures. I saw it as a record of time, and I didn’t think much further than that.

How did you make decisions around materials, like printing the photographs on braille?

When it came down to how to print the pictures, I decided to print them on braille, on these particular books that I had, because I think one of the things about what you can do with art is create symbols.

I had these photographs as a record, and I thought I’d like to print them on something that has a record too. And the record in this case was a novel by Iris Murdoch, which deals with British history from the Irish perspective. To me, that was enough. I think that thought process brought the work together.

The book was actually printed in 1968, which also is a symbol. I thought, why not bring all these things together? I think all these elements fit together and I personally don’t feel they need to be written and told, you know. I feel that the work should be able to present itself.

I think choosing vintage paper, also because of the quality of the paper, there’s certain preservation there. I feel all those elements I put into it without thinking.

You’d spoken in a conversation with Yasufumi Nakamori, curator of this series, about moving from 2019 into 2020, and noticing a desire to “feel” more into your work. I wonder if you could say more about that.

My work in a certain way has always existed as part of how I move about life. My work is stored with me. I also try to physically engage with my work, which means I print from a dark room. And I think in those processes, I bring in how I feel about the world.

Once you have a picture and it means something to you, you let it go. In my case, I let it go into something that is physical. That’s how I look at my pictures. If I can, I print everything, and I engage with it. This engagement is really where I also understand what I’m doing, you know. Because in that process, I can put things next to each other. I can create surfaces.

We had the pandemic and a lot of things suddenly, basically, reduced to what’s around you. I kind of liked that. There was a particular sense of tactility. All these kids came out, they’d written signs and there was a presence there. I wanted that to be part of the work.

That’s why I thought braille is actually quite interesting, because it’s something that really only reads when you touch it. I can work through material into ideas. I feel that my work starts with the photograph, but then it takes a journey for me to find the right place.

You’ve created a terrific amount of work photographing Black people. Do you see it as liberatory? Do you see it as documentary? I feel like this can be an oppressive question sometimes, or can feel like a burden — having to carry our historical realities with us on our backs. Do you think with these particular pictures, that there is an intersection with activism? How do you think about that?

I think there’s two ways to read this when someone asks me a question like yours. I don’t think activism is the right word, but I go to a lot of demonstrations where I support the cause, and I usually take my camera with me. I feel like I’m not a proper activist because I was there to take pictures. But I think what it is for me is — and that’s why I said it before — it’s important how I feel about it. It’s important how I engage with it because that’s the priority to me in my work and my relationship to my work.

I considered it great privilege that I’ve survived for a very long time doing what I’m doing and not having to explain it to no one. I could say, yes, a lot of these things could fit into how I work, but they don’t influence my work. There’s always the possibility of being spontaneous. There’s always the possibility of being open to whatever comes to you. The pictures that I have, I collected over time, but I also lived over that time. I see a lot of things through looking at people. Once my work goes out, people can take it to many places.

I wouldn’t call it a private enterprise because I’ve been doing it for too long, but it has a certain integrity for me where I don’t really want to speak to nobody. You know, I think the things that I look at for me are very obvious. If I photograph a person, I look for the thing that makes them represent themselves. I try not to put anything on them. Essentially, it’s an experience of other human beings. And I find that terribly interesting, where people take it. I can only hope to good places, but I’m not dictating where they should go.

This thing of whether that’s a burden for me, there’s no question I’m enjoying myself. As human beings, we are so much more than a picture can tell.

I want to ask you about word choice, and the way that you name things. Like your archival series Black Balloon Archive.

I work a lot in sketchbooks. There will be a show actually in the Tate, I think in July, where they will show some of my sketch work. I call it sketch work, but really it’s books where I’ve put all the pictures in. It’s kind of one of those things where I didn’t realize what I had. Up to then, I just did what I did, and that was it. I said “Okay, I need a name,” but I never work very much with words.

I actually started with writing. I worked as a journalist for a little bit, but I gave that up completely. In fact, I developed a certain kind of phobia towards writing, so I worked everything out in pictures. When I decided I needed a title, I just took from the things that were around me. I was listening to this song, “Black Balloons” by Syl Johnson. So the title came from the songs that I was listening to at the time, and ‘Archive’ simply because I thought I need to take myself seriously. And if I need to take myself seriously, if I look at the boxes and boxes that I need to start sorting out, it means there must be a purpose.

I have actually, through this engagement, learned to create narratives, which I’m very interested in. I thought, yes, I liked narratives. When I do my shows, I feel that the narrative is the title, like in the South London Gallery my show title was If You Know The Beginning, The End Is Not Trouble. That was simply a good way to enter the place, without being burdened, just to take things in.

And how about Time Don’t Run Here?

For Time Don’t Run Here, I wanted something with time. This idea of time and running. No one really knows what it means. “What does it mean, Time Don’t Run Here?” I liked that quality. It interests me, using words, because they usually come out of being open to the question, “What do I need?”

“Time Don’t Run Here” is now available through Tate’s website.