When Bong Joon-ho won numerous Oscars earlier this year for Parasite, it was a milestone for world cinema. The South Korean comedy-thriller about a family of hustlers was the first non-English language film in the awards’ 92-year history to take home Best Picture, a left-field surprise for many award season pundits. With Parasite’s American success, South Korean cinema was hailed as finally breaking into the western mainstream — something that had been gathering momentum for years with films like Snowpiercer, Train to Busan, Okja, Oldboy, The Handmaiden, Burning and The Good, the Bad and the Weird all being warmly received by Anglo-American audiences.

Most art house cinema-goers in English-speaking countries can probably name a handful of South Korean filmmakers — Bong Joon-ho, Park Chan-wook, Lee Chang-dong, Na Hong-jin and Hong Sangsoo all have had varying levels of success in the western world — but I imagine even the most self-proclaimed film buff would struggle to name more than a single female filmmaker from South Korea.

But while Korea’s female filmmakers have yet to break into the western market, that doesn’t mean there aren’t numerous women directing in the country. “In the independent sector, female directors are very active in making drama films and documentaries,” says Lim Sun-ae, who has just released her debut film, An Old Lady, which is currently playing at the London Korean Film Festival. “But the number of women directors is much lower than of men, so without thinking [people] resign themselves to the idea that it’s really difficult for women to start out as commercial film directors.”

Based on a true story, Lim’s film is about a 69-year-old woman who, after being raped by her physical therapist, struggles to get anyone to believe her. While recent American films responding to the #MeToo movement — The Assistant by Kitty Green and Promising Young Woman by Emerald Fennell — have been about young, middle-class protagonists, Lim wanted to focus on the many sexual assault cases where the victim is elderly. “There have been a lot of films dealing with sexual violence, yet not where the victims are elderly women,” she explains. “I was interested in stories yet untold — in this case, the elderly women sitting in a ‘blind spot’ amongst sexual violence crimes. The issue of sexual violence opened the door to the story, but what I really wanted to talk about was the prejudiced and discriminatory gaze through which our society looks upon the elderly.”

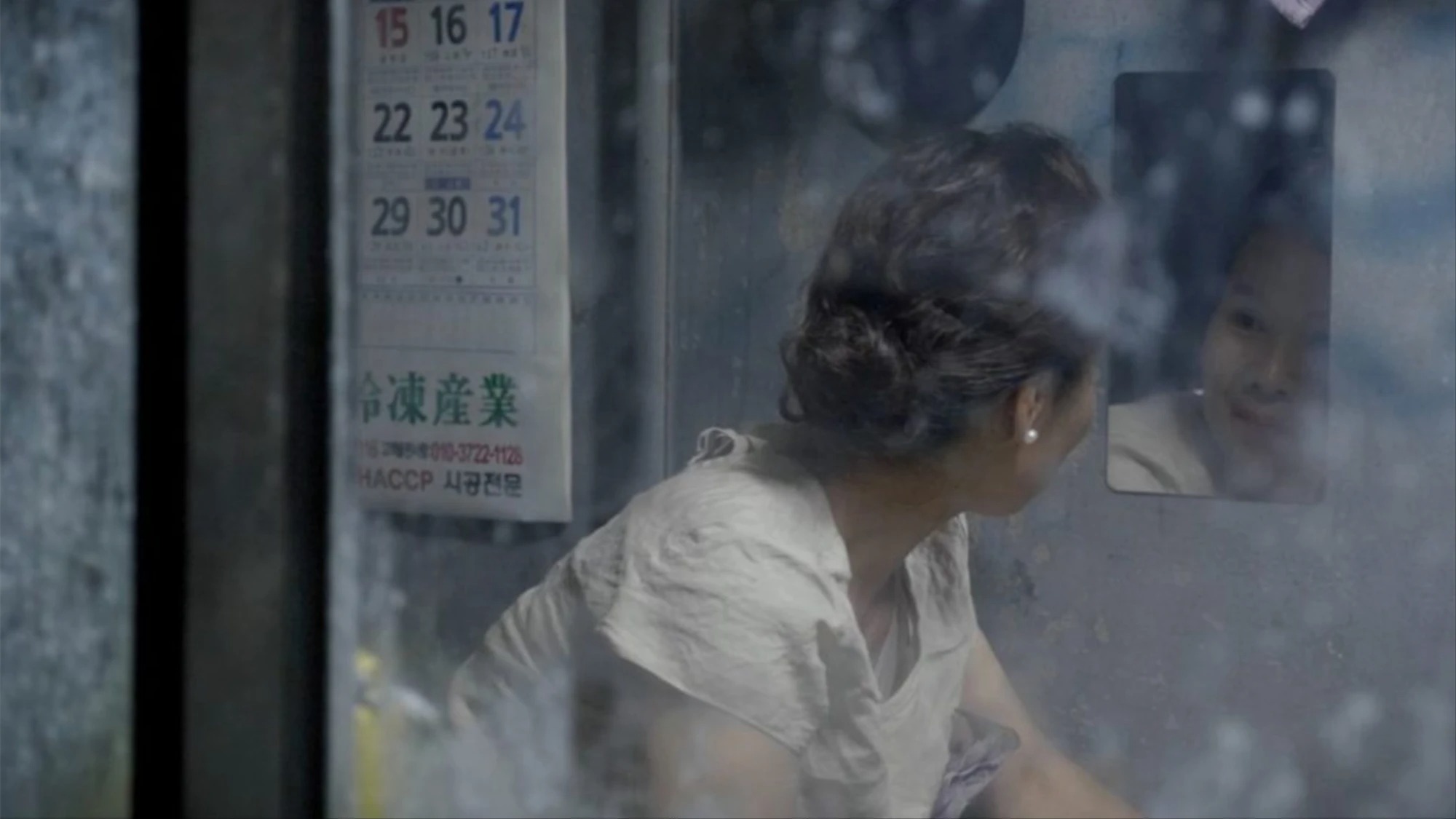

Another film that looks at sexual violence at the London Korean Film Festival is Kim Mi-jo’s Gull. Similar to An Old Lady, Kim’s film is a character study about O-bok, a middle-aged, working-class woman who is assaulted while drinking with her fish-market colleagues. Like Lim, Kim was inspired by the same incident when a woman in her 60s was raped by a nurse. In reality, that woman committed suicide, but Kim wanted to not only “depict reality but, at the same time, an alternative response to [it].” In Gull, O-bok slowly recovers from her assault which Kim calls a “fantasy element” to the film. “If this happened in real life she would leave the market and choose a life in seclusion. That would be more probable within Korean society.”

The South Korean film industry is currently undergoing what many are calling a “female film new wave” with more and more women working behind the scenes and moving into the director’s seat. “There are a lot of other women directors around me who within the space of two to three years of releasing a film, have signed the contract for their next one and are writing the script,” says Lim. “I don’t think it’s a fleeting phenomenon — it comes from firmly implanted roots. In twenty or thirty years’ time, I believe they might even surpass the men in numbers.” While some female filmmakers, like Lim and Kim, are directly tackling attitudes around gender inequality in their work, this new wave of female directors are making films about a wide range of subjects — just like their male peers. Yoon Ga-eun’s divorce drama The House of Us, Yim Soon-rye’s millennial comedy Little Forest and Lee Hyeon-joo’s lesbian romance Our Love Story are recent stand-out examples of the diversity of this new wave.

In 2017, South Korean film auteur Kim Ki-duk was accused of assault by an anonymous actor, and the next year accused of sexual misconduct by three more women. These allegations led to an outcry that parallels Hollywood’s #MeToo movement and a more frank discussion about gender inequality in the industry. “It is now obligatory to undergo training on sexual harassment and sexual violence prevention before commencing filming, and sensitivity to gender issues on set has definitely improved,” explains Lim. Recent works like the book Kim Ji-Young, Born 1982 have sparked more open conversations about sexual inequality and gendered violence in South Korean society, but Kim Mi-jo thinks there’s still a long way to go. “Prejudice against victims of sexual violence still lingers around,” she told Variety. “Seeing the woman as a contributor in sexual assault, or a bias that older women can’t be a target of sex crimes — these are typical examples.”

But Lim and Kim are just two of the many filmmakers pushing back against these internalised beliefs with deep roots in Korean society. And, as more women are given a seat at the table to make their films, attitudes are changing, albeit slowly. As Lim says: “We can’t just wait for people to change their attitudes — it is only when we bring these issues to the public eye, enforce measures, and propose new legislation that people’s attitudes finally begin to change.” Not only is this new wave of Korean female filmmakers helping to change society, they’re also enriching the Korean film industry with their art, and cinema, across the world, is all the better for it.

The London Korean Film Festival 2020 runs from 29 October – 12 November with online screenings available to audiences across the UK. For further information and tickets: koreanfilm.co.uk