Oh, to get on a plane going somewhere, anywhere! To most of us, the idea of jetting off seems like a distant fantasy. For Virgil Abloh, it is the ultimate nostalgic throwback. Before the pandemic hit, the fashion designer and all-round polymath travelled 310 days of the year, racking up infinite air miles and bringing his panoramic view of the world to his vision for Louis Vuitton, arguably the most luxurious purveyor of travel luggage. To say that Virgil was a jet-setter would be an understatement, least so because the idea of crossing borders and breaking down barriers — whether that be of countries or, more figuratively, genres, aesthetics, cultures and race — has been central to his vision for the monolithic French brand. The Chicago-born designer’s AW21 menswear collection continued to explore those very notions of travel and escapism, both from the confines of our homes and the societal structures further afield.

Set in a luxe malachite marble-floored airport lounge (first-class, of course), the show took place in Paris and was presided over by Saul Williams and Yasiin Bey (AKA Mos Def), who both performed as models hurriedly crossed paths en route to their departure gates. The idea behind the collection was to explore the symbolism of the way we dress, and the biased presumptions we make about people based on their clothes. “The collection strives to illuminate and neutralise the prejudice we create around people by keeping the dress codes related to certain archetypes, but changing the human values we associate with them,” read Virgil’s show notes. “The message is humanitarian: creating the same opportunities, dreams, and freedom for children of all races, genders and sexualities when asked the question, “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

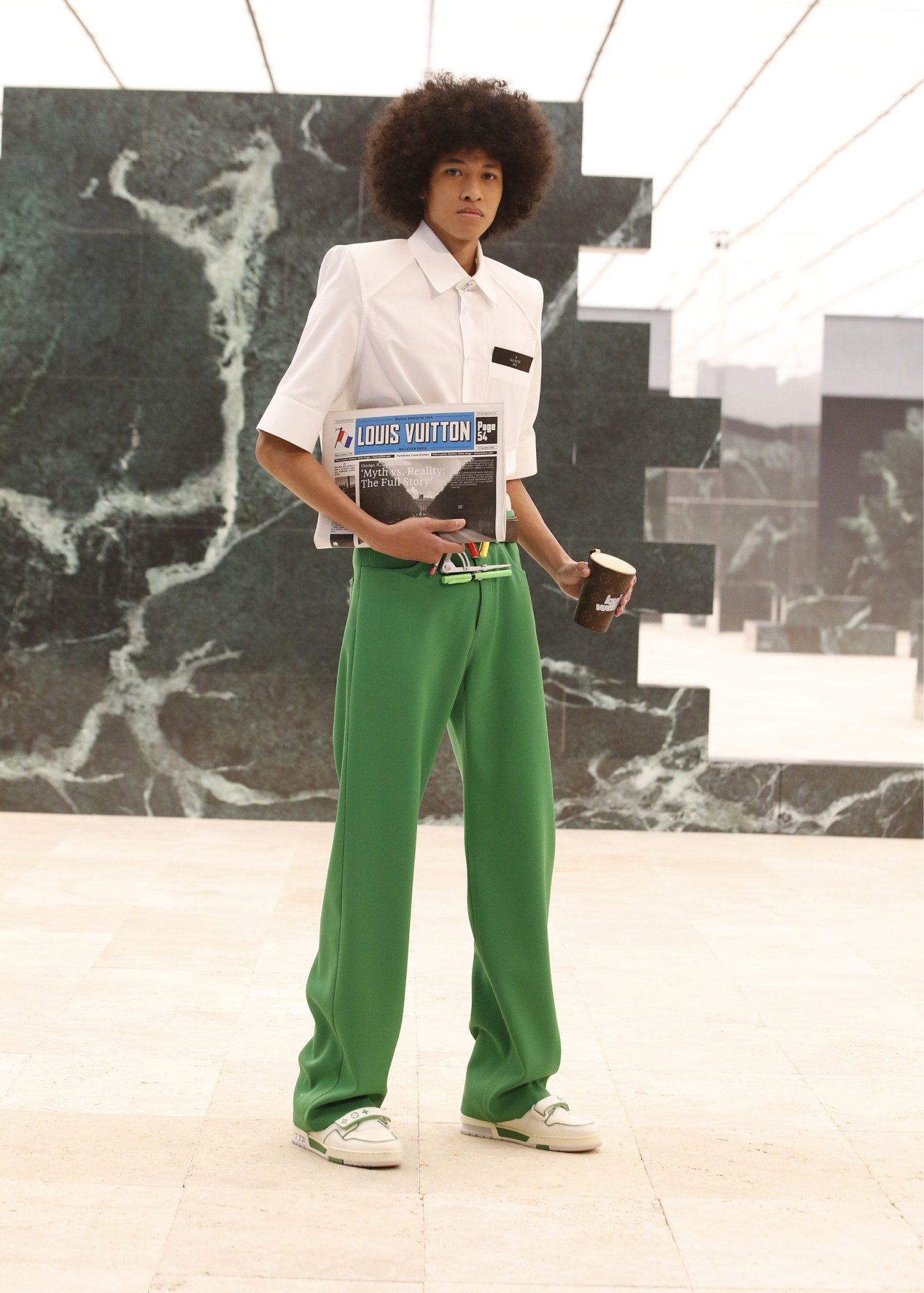

There were nods to classical sartorial tropes: cowboy Stetsons, city-slicker tailoring, security-guard vests, collegiate varsity jackets, Cuban-link chains, pimp coats, quotidian denim and baseball caps. In other words, clothes that inherently signify an identity, uniforms that indicate a profession, clothes that are ciphers for who that person is and what they might sound like, what music they may listen to, or the beliefs they may hold. Often, those presumptions relate to cultural background, gender, and sexuality — or, as Virgil puts it, “the unconscious biases instilled in our collective psyche by the archaic norms of society”.

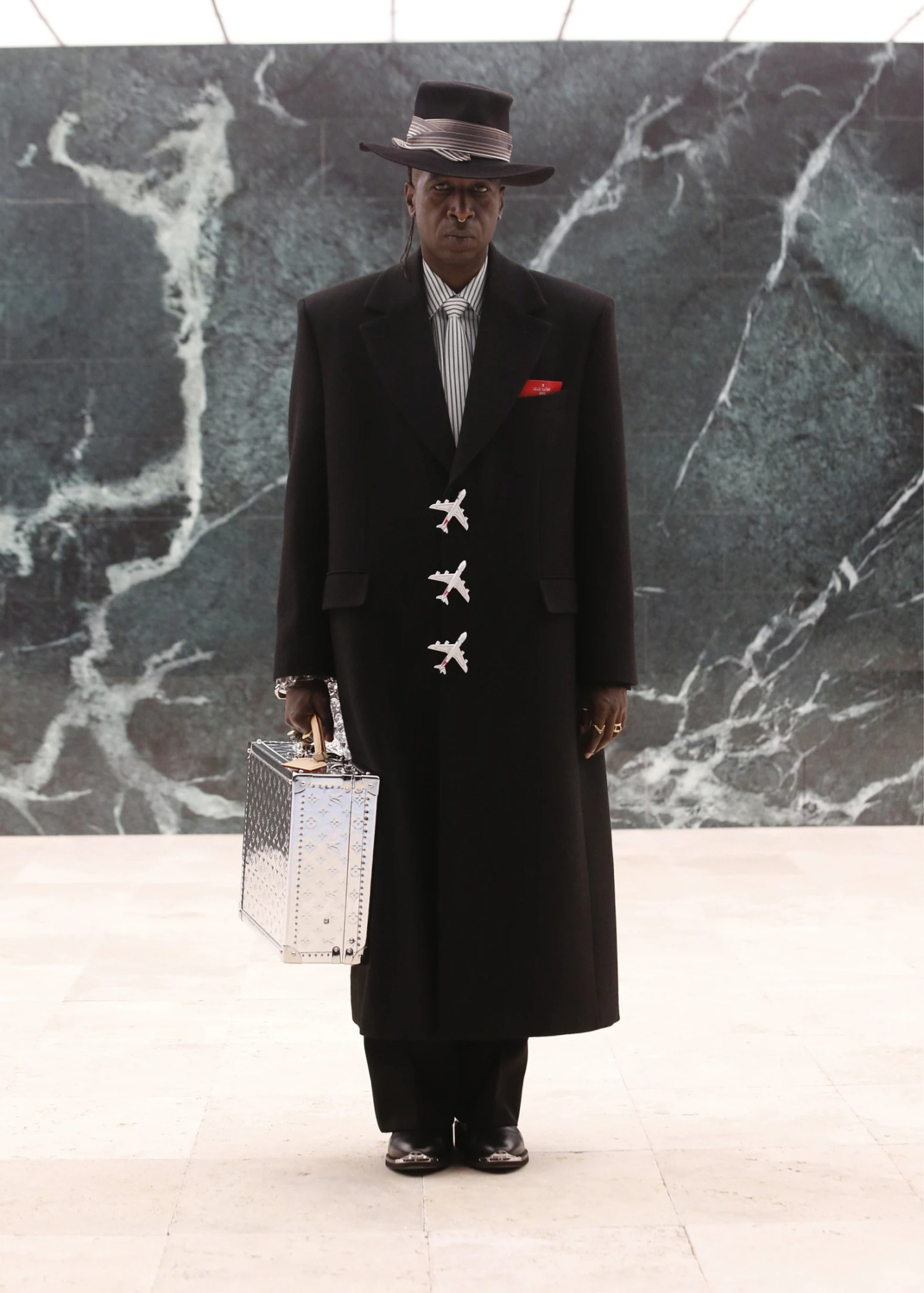

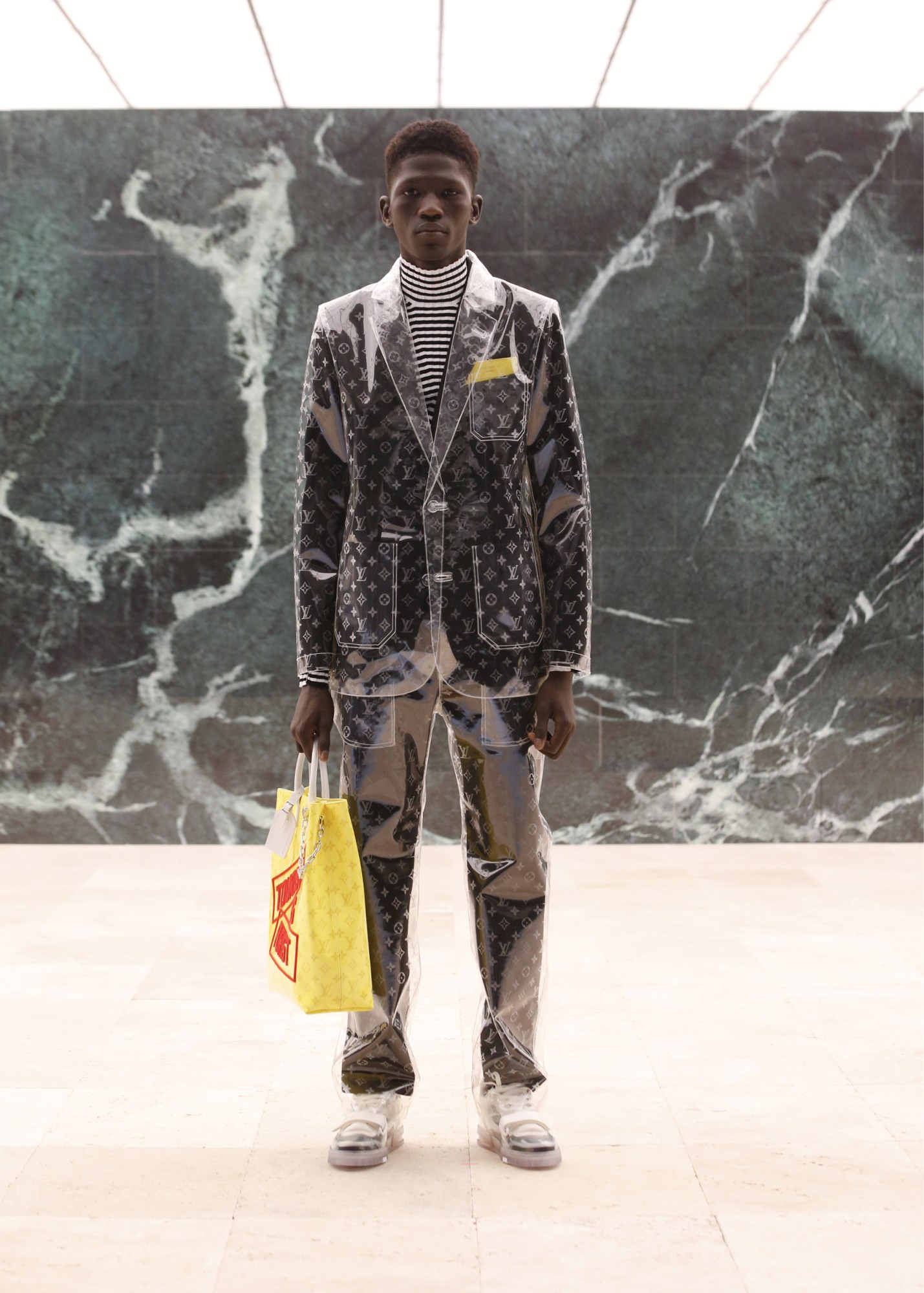

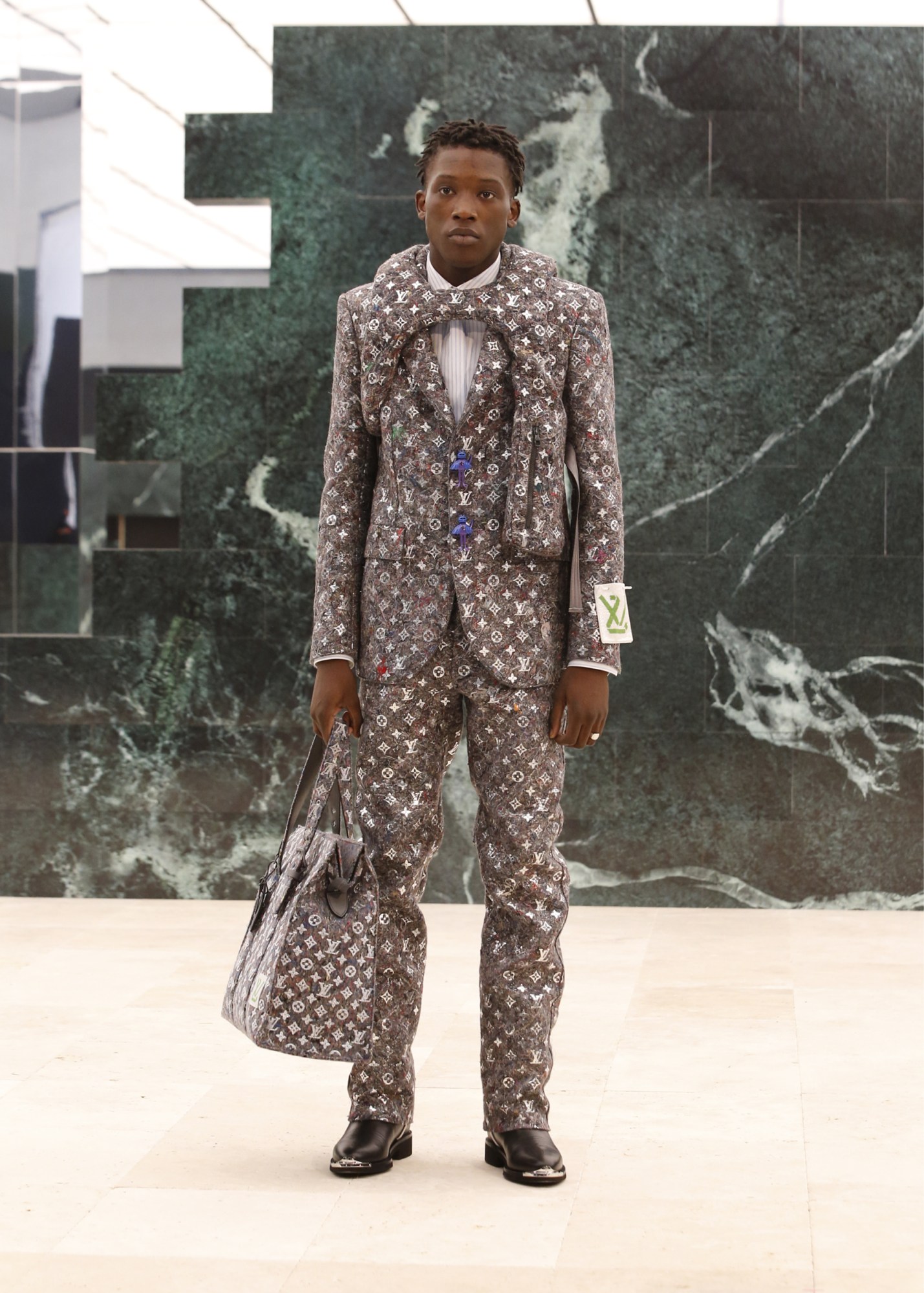

Put simply, he sought to fuck it all up and re-contextualise the archetypal tropes — his new versions are called “neotypes” — playfully mismatching them to create a tapestry of idiosyncratic characters who can’t be instantly pigeon-holed. There was no one precise look, but rather a curation of individual styles and enigmatic characters, each one given the stamp of LV’s monogram, and decked out in ultra-luxe fabrics and blinged-out bags brightly emblazoned with aphorisms conceived by artist Lawrence Weiner. Kente cloth, a nod to Virgil’s Ghanaian heritage, was remixed with Scottish tartan, draped across hoodies, denim and tailoring. Giant flower corsages were worn on lapels, while tiny aeroplane figurines replaced the buttons of coats and jackets. There were a million things to look at, but none of them could leave you with an overall impression of the person wearing them — except, maybe, that they’re someone who doesn’t need your judgement.

As one of the few Black designers at the helm of a major European house, the events in the months since his last show have not been lost on Virgil. Around the world, Black Lives Matter protests have made it clear how much is left to be achieved in the fight to end racism. One of the key references for Virgil’s collection was James Baldwin’s 1953 essay Stranger in the Village, which explored the parallels of his experiences as a Black man in both America and a small Swiss village (a prologue to the show featured Saul Williams crossing the snowy Alps, followed by a cast of Black figure skaters). “Baldwin’s essay also deals with what it feels like to be a Black artist in a world of art created from a white European perspective,” the show notes continued.

It’s difficult not to read into that as a personal vindication of Virgil’s own experiences, and it prompts some interesting questions: Why are people so quick to dismiss him as a fashion designer? Why do certain clothes mean certain things? Why do those meanings change when worn by different people? Is looking ‘normal’ a preserve of the privileged? As the show notes put it: “After the events of 2020, the collection proposes the notion that society has the opportunity to create a ‘new normal’ in which we free ourselves from the prejudice we create around people, ideas and art.” In other words: keep the clothes, change the values.