Louis Vuitton, L’Audacieux – ‘the audacious one’ – is a new book by novelist Caroline Bongrand, charting the life and times of Louis Vuitton, the French trunkmaker whose namesake house is now synonymous with the highest echelons of luxury. Its subtitle, ‘A Story’, hints at what is to be found inside: part-biography, part-fiction, it recasts Vuitton’s life as a kind of 19th-century fairytale – or Dickensian bildungsroman – seeing him rise from childhood poverty to the Emperor’s court, outfitting The Empress of the French, Eugénie de Montijo, with luggage to house her vast collection of gowns. (The book even comes complete with evil stepmother.)

At the heart of the tale though is the idea of travel: from a young Vuitton walking solo to Paris to find his fortune, to his role as packer and box-maker for wealthy tourists who arrived in the city on grand European tours, the idea of luggage – both physical and metaphorical – has long defined the house. This stretches all the way to present day, as creative director Nicolas Ghesquière and the late Virgil Abloh interpreted these roots for a new era of shoppers. “I want to use Louis Vuitton’s history with travel to really look at different cultures around the world to help make all our humanity visible,” the latter said, when he was appointed to head up the house’s menswear. He used this idea to theme his campaigns, photographed around the globe.

But how much do we really know about Louis Vuitton himself? Despite the ubiquity of his name, the finer details of the house founder are little-known – something Bongrand teasingly explores in the novel, melding previously unpublished facts with an eye for fiction, “turning his own life into an epic tale”, as the blurb describes. Here, eight things you might not know about the life of Louis Vuitton, unpicking fact from fiction.

1. He grew up poor

This much is true: Vuitton was born in Anchay, Jura, a mountainous region on France’s eastern border. In the book, a young Vuitton and his siblings live in a tiny one-room mill owned by his father – Vuitton’s mother does not appear in the book except as a tender memory, having died when he was 10 – ruled over by an “evil stepmother” who puts the children to work and takes the prime sleeping spot closest to the fire. Though the legend of this Cinderella-esque villain has been documented prior to Bongrand’s novel, we will never know the true extent of their relationship – what we do know, though, is that Vuitton felt compelled to leave home with nothing to his name in 1835, aged just 13 years old.

2. And walked 400 miles to Paris on foot

In the novel – not unlike a fairy story – Vuitton enters the woodland of Jura with the aim to walk to Paris on foot, wearing only a pair of wooden clogs. The time in Bongrand’s dark forest leads him to think of a younger brother, also called Louis, who died before he knew him. “Was it up to him to fill the gap left by the lost life? But how do you live two lives? By living more intensely? By experiencing more?” Bongrand writes, with plenty of foreshadowing. The 400-mile journey sees him pick up odd jobs along the way, and in reality took two years, with a dishevelled Vuitton turning up in Paris in 1837.

3. He came up in a moment of change

The Paris he encountered was one on the verge of change: the king, Louis Philippe I, had come into power in 1830, taking over from his cousin King Charles X, who had fallen after a deeply unpopular reign (“it was a family betrayal,” writes Bongrand on the takeover). Louis Phillippe’s own time in power would prove unpopular, too, with the citizens of Paris unhappy with a lack of improvements in their lives, eventually leading to riots as poverty ravaged the city. A young Vuitton was an apprentice at the atelier of Monsieur Maréchal – a trunk-making and packing company – and Bongrand shows him watching as the city sparks into revolt around him. The riots would lead to Louis Philippe’s own abdication, and the advent of the Second Republic, which was eventually ruled by Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte (Napoleon III) as emperor after a coup d’état.

4. He befriended an Empress

Working at Maréchal, he began to encounter the city’s elites, who needed packers and trunks to transport their belongings between their various homes. Bongrand shows a young Vuitton seduced by this new world – at one point literally, depicting him losing his virginity to a duchess in a three-day affair (“nothing but sweat, screams and voluptuousness,” writes Bongrand). But it is his relationship with Eugénie de Montijo, who would go on to marry Napoleon III and become Empress of the French, which is central to the novel and more grounded in fact: Bongrand depicts his relationship with her as one of ongoing confidante, though all we really know is that Vuitton was made official packer and trunkmaker for her household in 1853.

5. Fashion was important from the beginning

A year later, in 1854, Vuitton founded his eponymous store. “Securely packs the most fragile objects. Specialising in packing fashions,” read the sign at 4 Rue Neuve-des-Capucines. Vuitton had noticed the necessity for a means to pack the increasingly luxurious gowns of Empress Eugénie, and the women of her court. Much of his fascination with fashion, Bongrand writes, came from his relationship with Lincolnshire-born designer Charles Frederick Worth – known as the father of haute couture – who taught him the changing needs of fashion. Vuitton knew that women would need help transporting these creations, a feeling compounded by a surge in travel, as new hotels in Paris began to welcome wealthy tourists from around the world.

6. Vuitton was an inventor

In the acknowledgements to Louis Vuitton, L’Audacieux, Bongrand thanks the staff of the Louis Vuitton workshop in Asnières for teaching her the art of building a trunk – in the novel, these details provide one of the narrative arcs, as Vuitton seeks to continue to innovate his luggage for his clients’ changing needs. From brushing canvas with resin to make it waterproof (Bongrand shows him delighting in “mistreating the trunk” by dousing it with water) to the eventual creation of his signature rectangular “flat” trunk, created to be convenient for journeys by train, Vuitton was an innovator at heart.

7. His daughter was born in the store

Or so Bongrand’s story goes – after his marriage to Clémence Emilie Parriaux in 1854, Vuitton’s daughter was born the year after in the back of the store on Rue Neuve-des-Capucines (records show her place of birth simply as Paris). Whether true or not, it serves as a metaphor for the importance of family to Vuitton: after his retirement, his son Georges took over, and would be the one to introduce the house’s now-signature LV monogram.

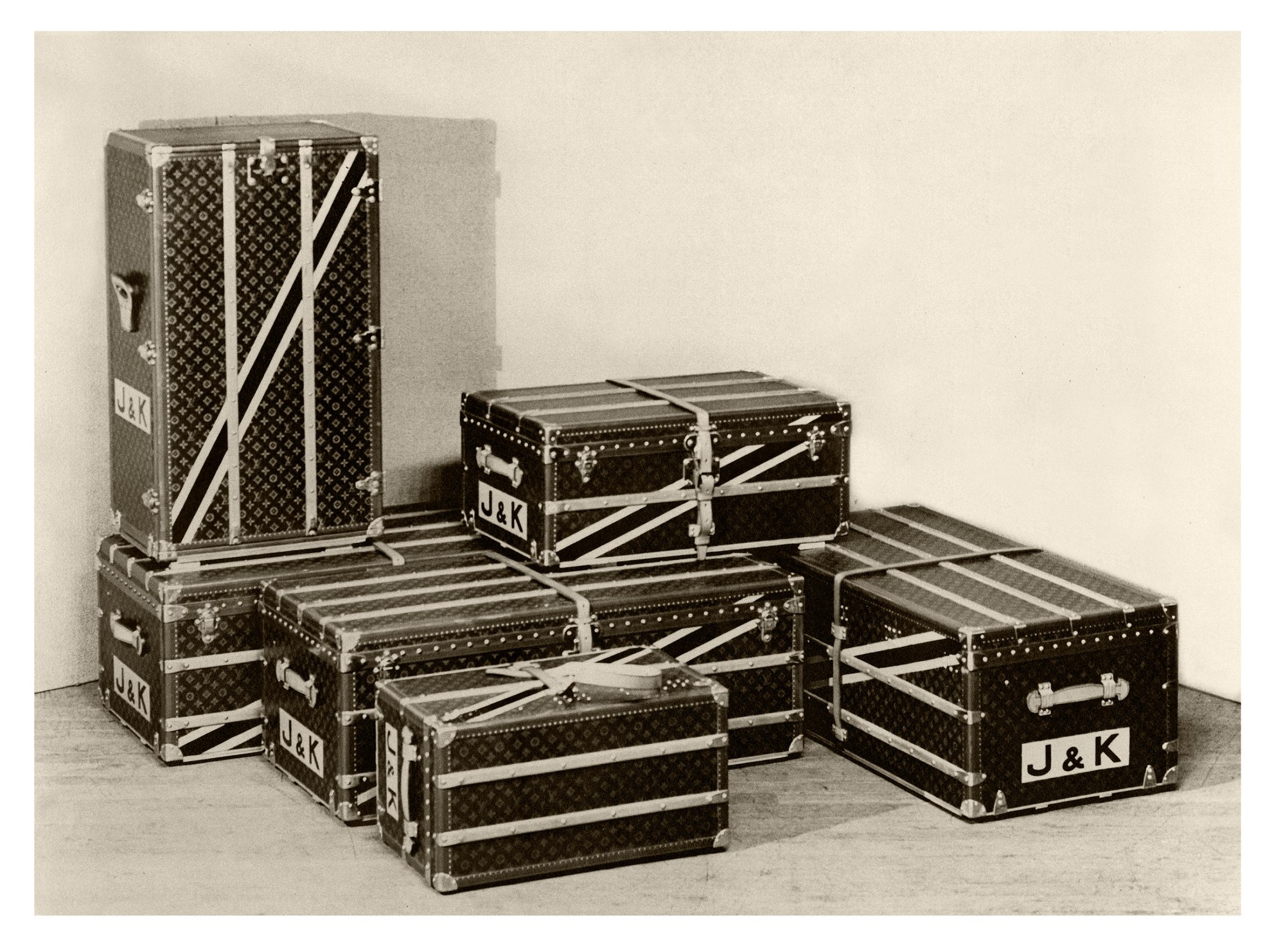

8. The Vuitton workshop was invaded

Part of the reason we know so little about the early years of Louis Vuitton was due to the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war, and the subsequent invasion of Vuitton’s Asnières workshop by Prussian troops, who occupied the factory for four months. Trunks and equipment was stolen or ransacked, his workers fled, and most of the documents about the company were destroyed. Vuitton himself was left with nothing. Over the next years, he slowly rebuilt the factory, and shifted from packing trunks to luggage – eventually creating portable wardrobes, as well as Louis Vuitton’s very first handbags. They would ensure the survival of his namesake house long after his death on February 27, 1892, in Asnières, the Parisian district where he’d built his now centuries-spanning empire.