“There are many advantages of having the experience of being both an outsider born somewhere else and an insider,” said artist Lubaina Himid, who was born in Zanzibar, Tanzania, but moved with her mother to the UK as a baby. “One of the most obvious is the ability to see both sides, and act as a cultural broker between those on the inside and those on the margins.” Himid’s work, collected by the Tate and awarded the prestigious Turner Prize in 2017, is now heading across the Atlantic to be featured at the New Museum in New York in “Lubaina Himid: Work from Underneath” (on view June 26 to September 22).

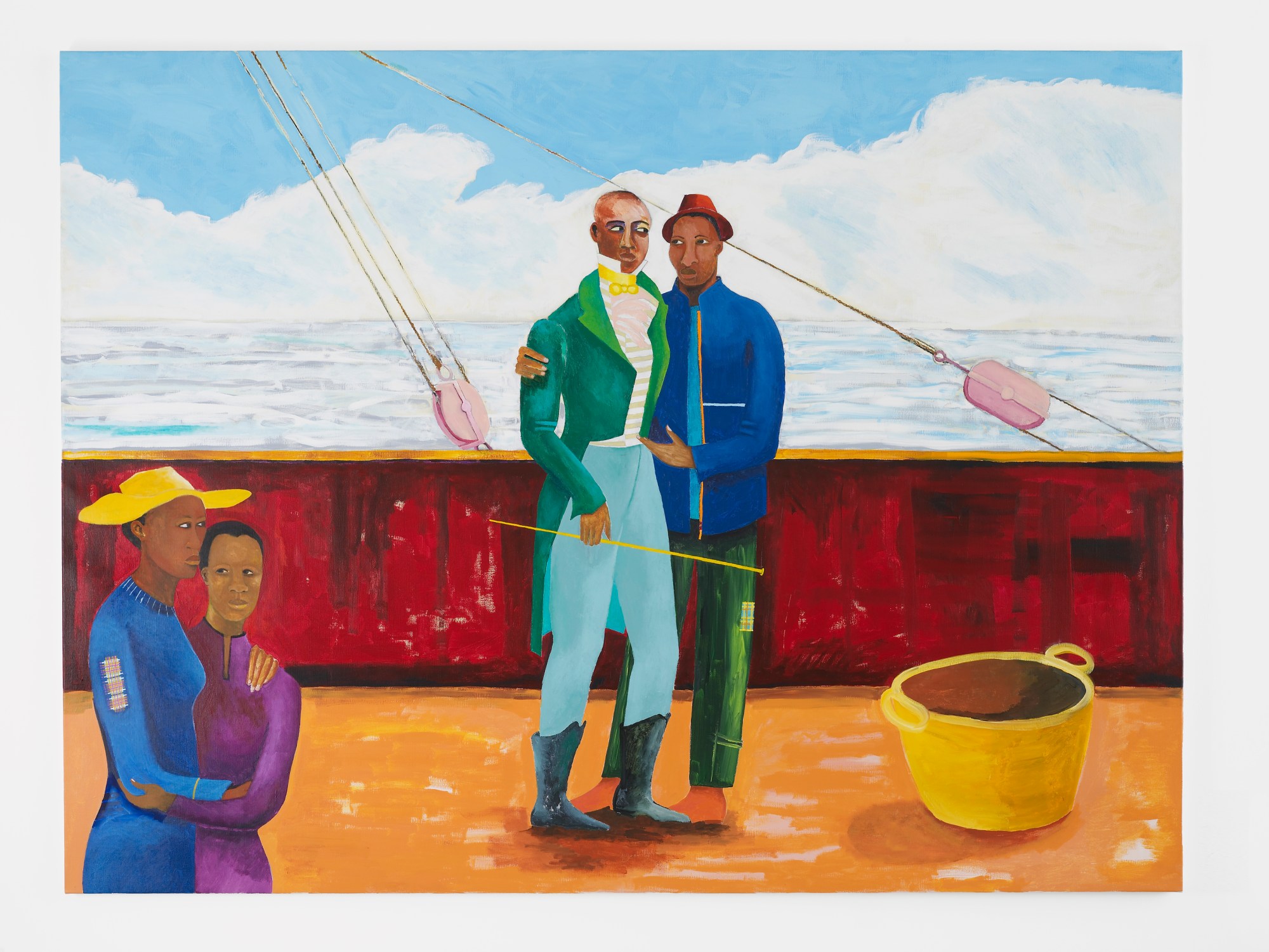

Championing black voices and visibility, Himid’s work explores the influence of the African diaspora on British culture and widening this understanding has been a motivator throughout her career. Himid’s art — often laid out in an immersive mise-en-scène rather than passively hanging on the walls — confronts the legacy of colonialism and puts racial identity squarely in the public forum. Her paintings are bright and graphic, and she repurposes quotidian items by adding visuals and by extension, fresh meanings. The show’s centerpiece is a 15-foot wooden ship wedged within the building.

While Himid feels there is still much institutional discrimination to fight, she noted: “The next generation of artists are already extremely clever about working together, making themselves more visible and taking on the establishment in a way that we could only dream of.”

We spoke with the artist about navigating between past and present, the power of caricature, and how small gestures ultimately fuel larger-scale activism.

You’ll be showing new pieces. Are there any notable differences between your current and past body of work?

I have been making and showing work on a continuous basis since 1981. In the past, I have made work which uses the found object—plates, tureens, jugs, jelly molds, even farm carts, and newspapers—as a basis for my paintings. This exhibition will be primarily paintings on wood, canvas, and metal. The new work asks questions and tries to find answers about how it is possible to build something meaningful for the future while we are still surrounded by the heavy and unresolved burdens of the past. The space will be one in which the trauma is ever-present, but where the road to resolution will attempt to emerge triumphant.

How does integrating words complement what you share visually?

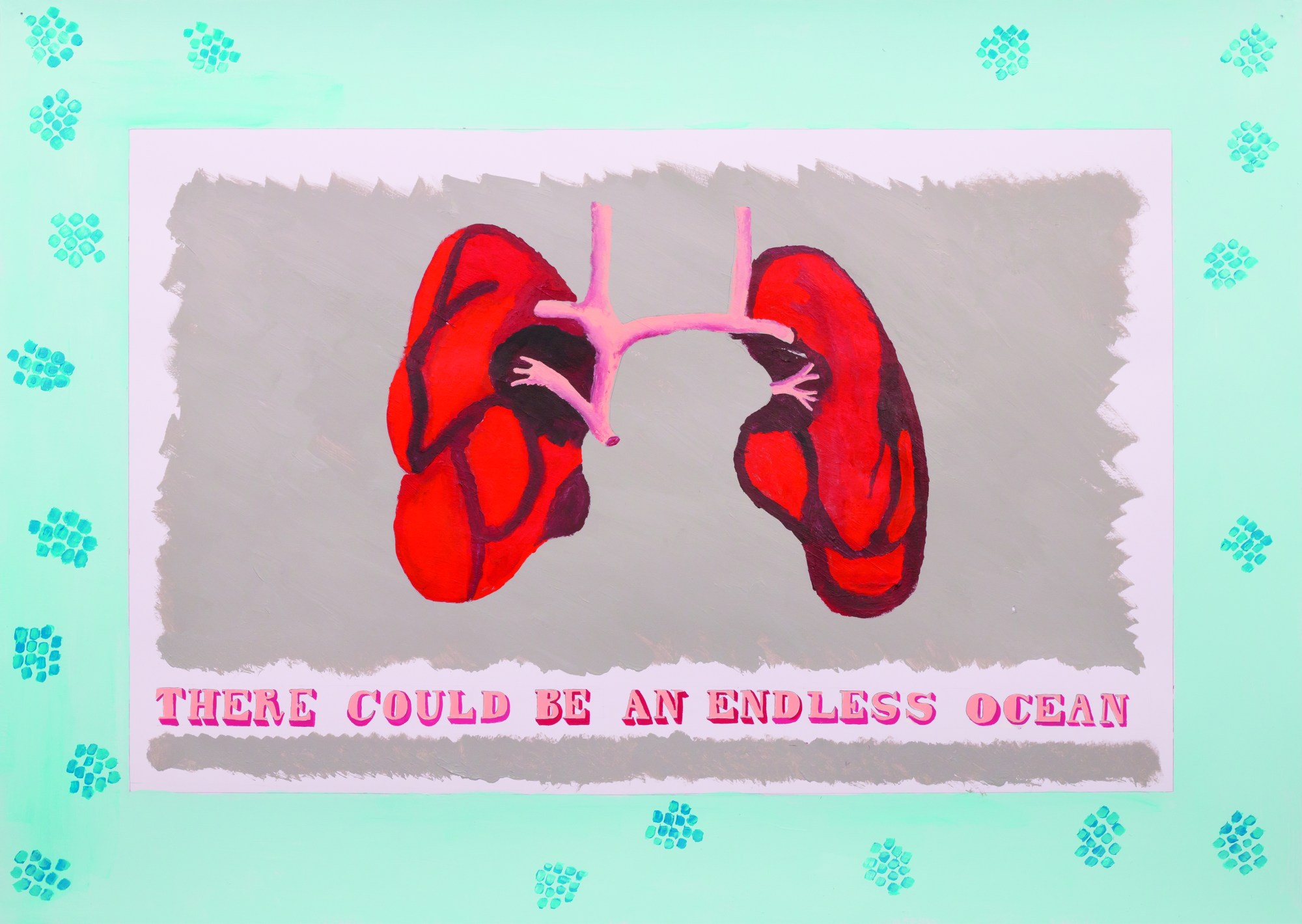

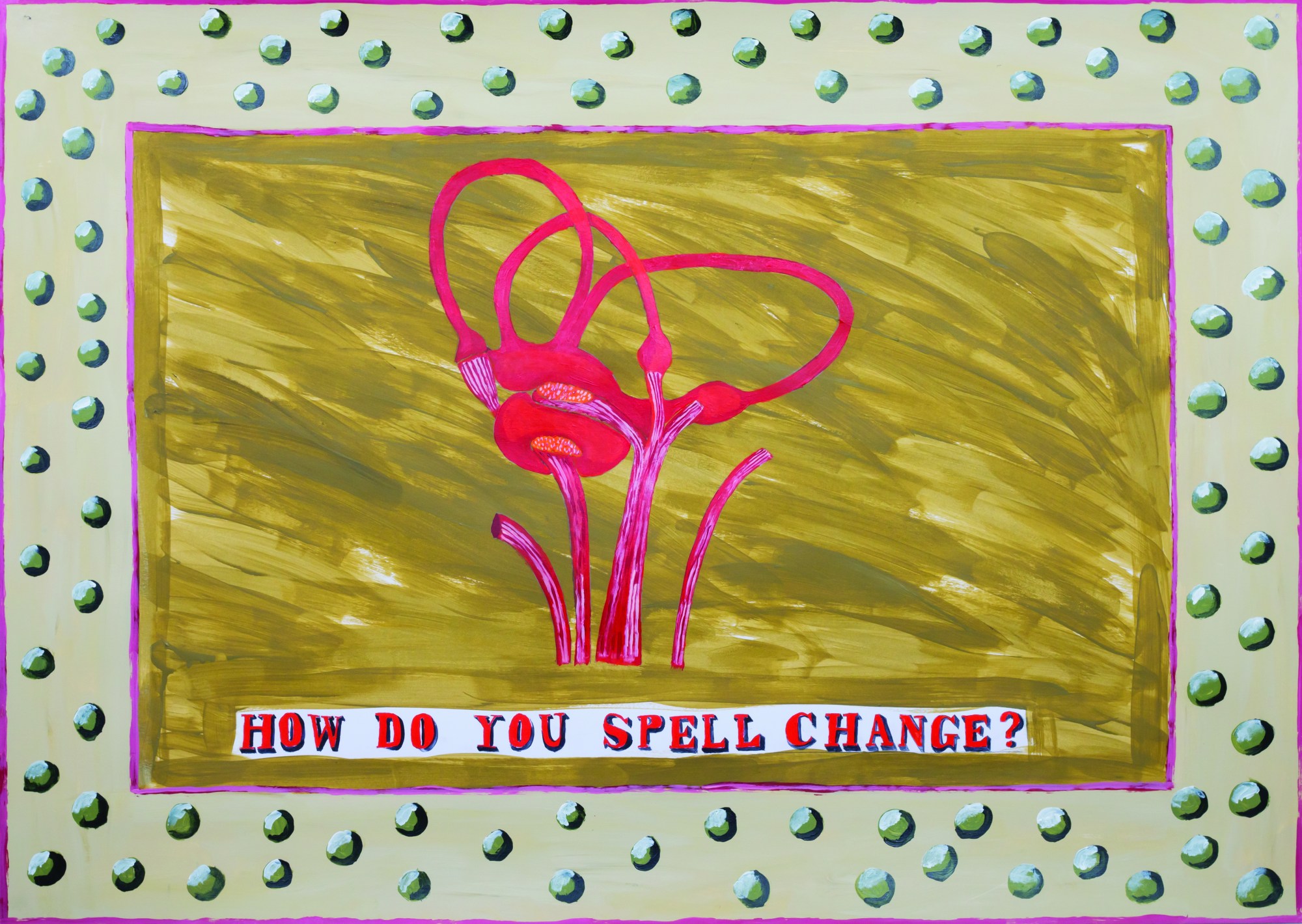

In this exhibition, the words depicted in the series of nine paintings on metal embedded into the wall—“Metal Handkerchiefs,” loosely based on the East African basic design of the Kanga—are taken from British health and safety guidelines. These are typically authoritarian, controlling, and over-cautious. But isolated as part of this series, they read more poetically and perhaps provide some amusement for those people who are obliged to be careful about how they negotiate their way through the everyday.

How did you decide on this exhibition title, “Work from Underneath”?

The title is practical [advice]: if you are working to fix a fragile roof, ‘work from underneath.’ It is about being strategic, about how to move forward from disaster. It also refers to the fact that traces of past histories lurk beneath the surface of everyday objects: in the fabric of buildings, in the nooks and crannies of furniture. We have to reveal these histories, scrape back the surfaces. If there is danger of some of this heavy history falling on top of us… the paintings I’m showing try to help us think of ways to work around the danger and understand the wisdom of negotiating, and feel what it might be like to have someone else’s life, in order to empathize.

You’ve been working as an artist for decades. How significantly have artistic institutions opened up their perspectives over the course of your career?

Artistic institutions have changed in part because there are new people running them: younger curators, more women in important positions. It’s debatable how long or how secure these changes are set to be, but while there are opportunities to be had for conversations, I am happy to try to build serious relationships with people who really want to encourage audiences to share the rich experience of engaging with art. There have been more opportunities through showing in art galleries, as opposed to historical museums, to broaden my audiences and this in turn has been influential, as I learn new languages of making and showing.

In the past, you’ve described your art as coupled with activism. How do you blend these effectively?

It’s important that audiences who engage with this show come away with the belief that even the small everyday actions that they carry out in collaboration with friends, family or colleagues can make a difference and could shift the balance of life in favor of positive change. I’d like people to feel that they might see ways to be more capable of being less risk averse.

The charged history and discussion around race in the U.S. is distinctive from the one in Britain. Are there things you could address differently in a New York context?

The history and discussion around race in the UK has been raging since at least the 1500s as this tiny maritime nation began to build its incredible wealth, power and global influence via the exploitation of people and land all over the world. Many of the issues we talk about in the UK—such as the lack of acknowledgement of the cultural contribution by people of the black diaspora, despite the very obvious physical evidence of present buildings and monuments at the heart of wealthy British cities—can be addressed with equal vigor in New York, where there are millions of traces of this historic presence and traumatic past still coursing through the veins of every street and building. What is different is that there might be more people passing through the gallery space who are used to engaging with how to tackle a future strategy than in the UK, where generally there is a national obsession with a selective version of the past. The idea that solutions for change might lie in ‘collective making’ as opposed to ‘individual striving’ are paramount in my work, as is the power of conversation and negotiation. These ways of being are relevant, whether we are in London or New York.

How does the role of satire or caricature complement aesthetics and historical themes in your work?

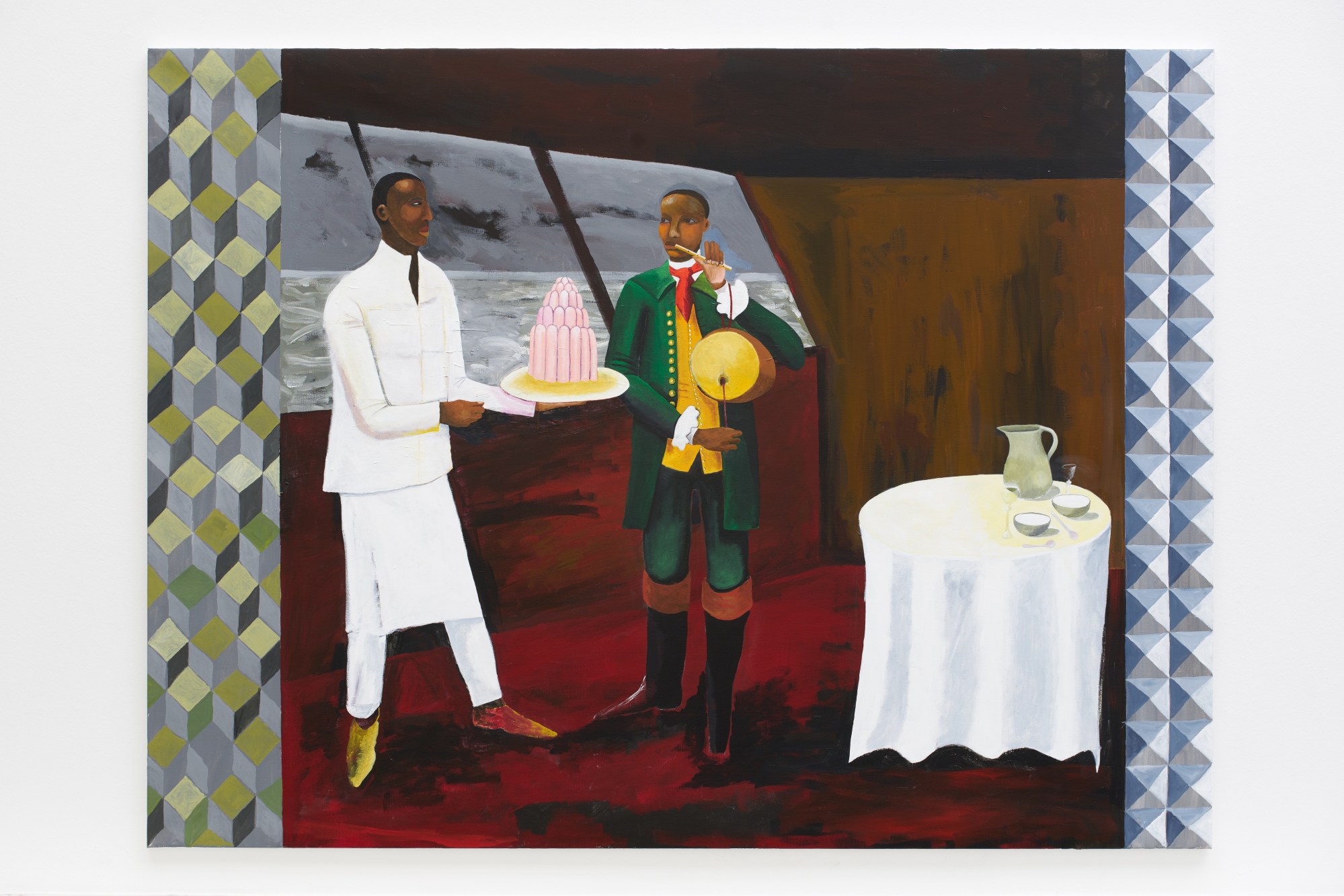

My interest in 18th and 19th century British caricature is at the center of an understanding of my more satirical work, such as “The Lancaster Dinner Service” and “A Fashionable Marriage.” This popular cultural form of the satirical mass-produced print was outrageous and cruel: the artists were allowed to mock and ridicule everyone in Britain, from tyrannical and vain members of royalty, greedy politicians and aristocrats, to enslaved and freed Africans, the poverty-stricken, and everyone who wasn’t British. Indirectly, these caricaturists left visual evidence about who populated the streets and theaters, drinking houses, and political arenas of their day. I am rather more selective; I use the aesthetics of the historical caricature to make people laugh and to see how it might be possible to disempower, if only for a moment, the vain, the pompous, the incompetent and the chronically greedy.

You use a variety of media… how do you decide on the right way to articulate an idea? Do you let ideas gestate or are you very spontaneous?

I trained as a theater designer as well as a cultural historian, and this means that I always have a plan! I’m constantly aware of the potential for everything. Anything can be the starting point, or even the actual surface, for a series of paintings. Ideas can gestate for years because I make new work all the time, which means that some of these ideas have had to wait in a queue. I make drawings, make notes and think things through at every possible opportunity: waiting for a kettle to boil, traveling on long train journeys. In recent years, I’ve been able to ask [my assistants] to spend months testing the feasibility of future projects while I work on the current ones. This method enables me to be quite spontaneous, albeit within my own tight parameters in the studio. I often make preliminary drawings and paintings on paper and usually have a plan as to how the work will look… I argue with myself over color in the studio, in front of a work, in the midst of the process. I mix colors as I go, building layers where needed but then erase and replace huge swathes of painted surface as I add others.

Having done a residency at The Guardian’s London offices, where you examined problematic or negligent juxtapositions within print media, what do you think is the way forward at a time when misinformation and sensationalism doesn’t seem to be slowing down?

There has always been misinformation, negligence, and sensationalism in the press and the media. Media works to tight yet often self-imposed deadlines and is racing against the new technology culture of rolling breaking news. The bottom line is that being fair and clear and honest and ‘inclusive’ is not what sells papers. There are many communities across the globe who are very used to living their lives in the best way that they can manage while being totally misrepresented or ignored or distorted. The only way to counteract this unfortunate established method for keeping social control is… to tell your own truths and to listen to others’ narratives. We have to be better at imagining and understanding other peoples’ lives, and try not to be indifferent to other peoples’ difficulties.