When an artwork from Lucien Smith’s graduate collection resold for $389,000, two years after his graduation, it sent art critics into a frenzy.

Some were fascinated. “He’s just 24, but Lucien Smith has arrived,” opened a T Magazine profile in 2013. Here was an artist who had ascended “from filling scrappy galleries with broom ready-mades to creating monumental oil paintings for blue-chip galleries and bigwig collectors” in the span of a few solo shows, wrote The New York Times a couple months later.

Others were less enthused. Art critic Walter Robinson coined the phrase ‘Zombie Formalism’ in 2014 in an essay for Artspace, referring to the surge in collectors buying and flipping the work of emerging artists like Lucien, for prices that did not reflect their quality. Regardless, to be experiencing more visibility than most artists could expect in a lifetime, Lucien’s proverbial arrival was undeniable.

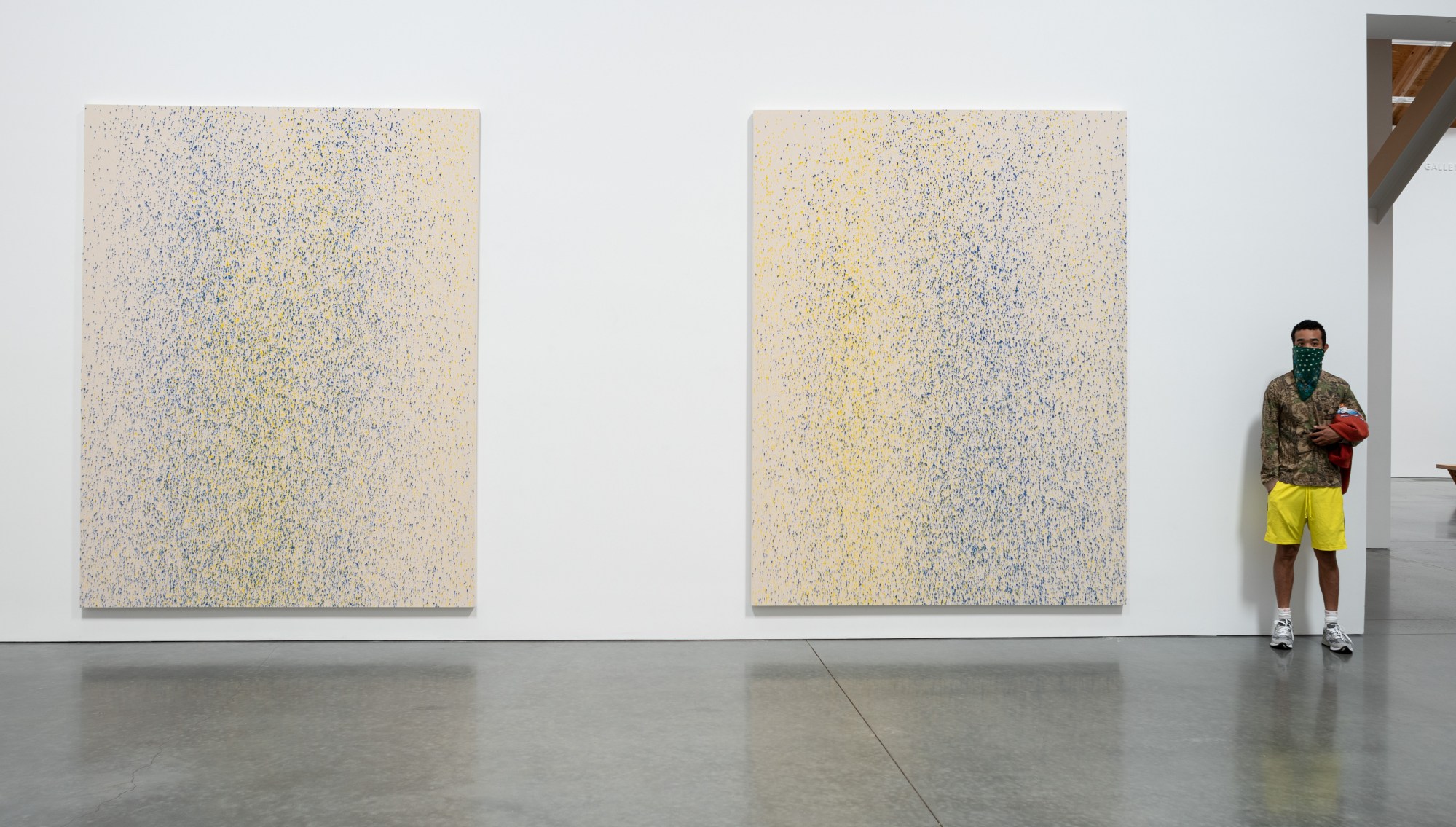

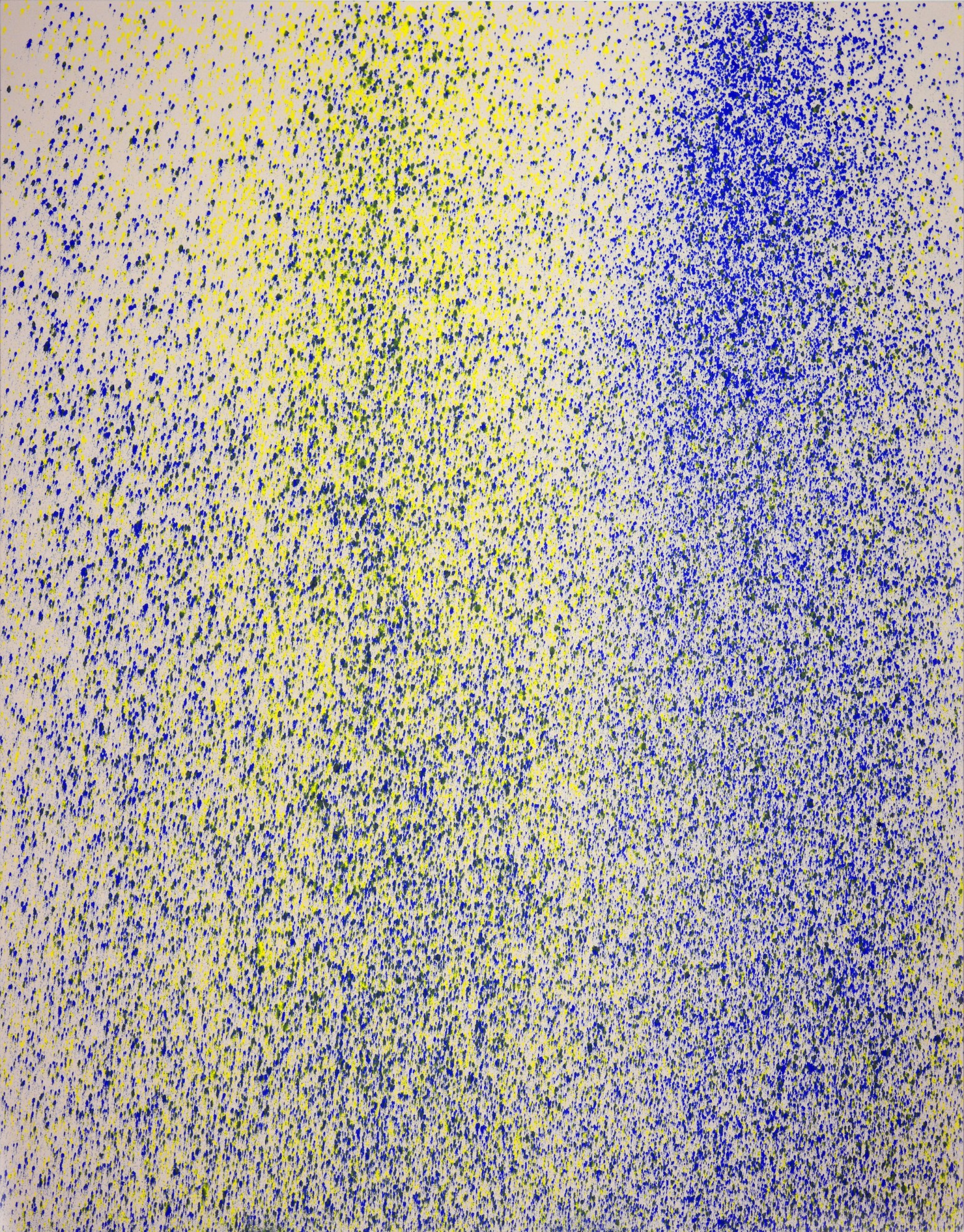

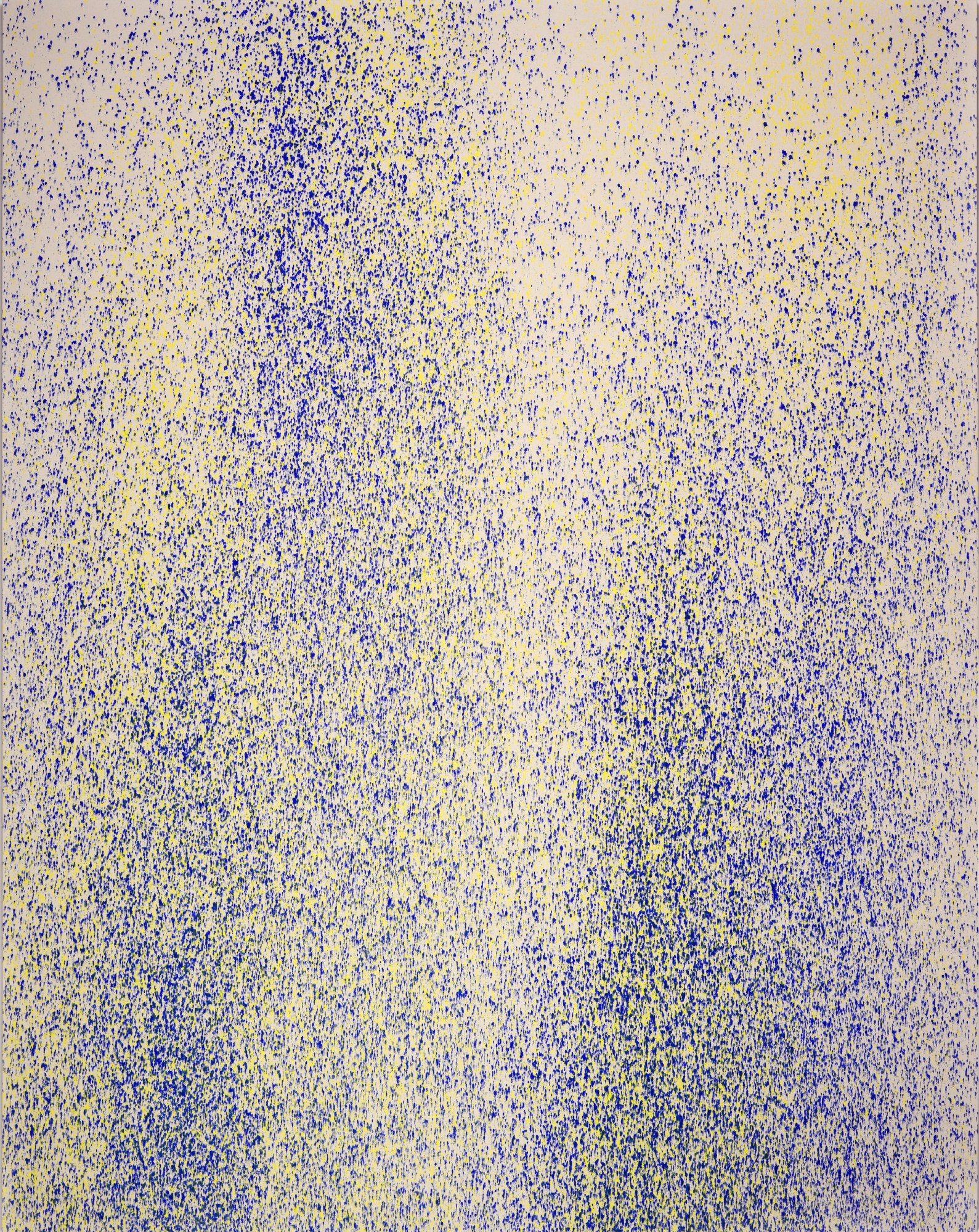

The Zombie Formalism ‘apocalypse’, as Artnet called it, has long since passed, and still Lucien’s work remains a feature of solo and group shows across New York, Los Angeles, Paris and London. A small number of artworks from his breakout Rain Paintings series, in which large canvases were sprayed with acrylic paint-filled fire extinguishers are now the subject of a new solo exhibition — Southampton Suite — his first in a museum. Like all good artworks, they remain as divisive now as when they were when first presented.

But Lucien’s main passion these days isn’t his own work, it’s that of others. Unenthused by the scene that he was once so inextricably linked with, speaking to him you get the impression that he couldn’t care less what other people think of his work either. Success has awarded him the chance to to start Serving the People, a nonprofit talent incubator set up in 2015, which provides young artists with support, programming and a commission-free sales platform and, for the first time since it began life five years ago, he believes it’s truly beginning to work.

You’re at home in Montauk on Long Island. What has your lockdown experience over the past few months been like?

I was actually speaking about this with someone earlier, not much has changed for me. I think I’ve been practising socially distancing and quarantining over the last few years. I mean, I obviously have to wear a mask when I go grocery shopping, but my day to day really isn’t that different.

I think of you as an artist who is quite integrated into the New York art scene. What do you think of it with a bit more distance?

It’s different. It’s definitely changed from like 2011-2012, I think it’s dispersed even, a lot of great New York artists aren’t even living in New York anymore, sadly. And from the younger generation of artists that I meet, it’s still there, I don’t think it’s as cliquey as it used to be. I think a lot of people now sort of — with social media and Instagram — are definitely spread much wider.

I definitely spent the majority of my early twenties very much involved in the New York City art scene and things like that. I still try to have some sort of presence, but I mostly have a digital involvement at this point. I haven’t actually been in New York City for a while. The stuff we’re doing with Serving the People or meeting with other artists it’s normally through Zoom and whatnot.

Tell us a bit more about Serving the People.

It’s about five years old, but this is pretty much the first year that it’s really started to work. I think a lot of that has to do with the social climate, and with people wanting to be more active in their communities, and doing more social engagement. This year, we’ve really started attacking our mission to be a creative incubator-slash-digital platform. We’ve been able to do a bunch of programming that has been helpful to younger artists. Even from launching our editorial and blog section to doing sort of shows with different universities. I think it’s been going well.

This year in particular, art has lent itself to being valuable in aiding global activism and charity. What do you think is an artist’s role in that space?

I guess I see it a little bit less formal than that. The artists are definitely artists on their own. I do think that we’re kind of moving into a territory where art isn’t necessarily about like, the tangible anymore: the painting or the object. It’s more about the effectiveness or the reach it has on an audience. It’s great when artists are donating their work to charity, or those sales for charity and things like that, but I’m more interested in what ideas those artists have about doing programming, or community engagement that isn’t necessarily revolving around an artwork per se.

Could you talk a little bit about Southampton Suite as a collection, and it being your first solo museum exhibition?

They’re works that I made in 2013. They’re pretty much the highlights of a body of work, the Rain Paintings, that kind of got the ball rolling for me. So to see them years later in an institutional context is definitely rewarding — a dream of mine come true. And it also is kind of pushing the ball forward with STP as far as me having confidence and believing that we can do great things without the gallery support. Without being part of the art world, or the art market.

A quote from the show notes reads “A lot of people doubt I could get here without a gallery and without playing ball with the art world”. For those who don’t know much about the inner mechanics of the art industry, what does “playing ball” actually involve and how does it limit an artist’s freedom?

The way that it’s set up is that an artist is really an employee of the gallery. And that’s something I really trouble dealing with, because I think the gallery system, art advisors and curators, these are people that have figured out how to monetise and create jobs for themselves based in the creative world. I think a lot of that power has been taken away from the artists, and so what I mean by ‘playing ball’ is that artists will have to do and make artwork at the beck and call of the gallery in order to satisfy its clientele. [They’ll have to] basically manipulate the lack of transparency.

A lot of times, for example, institutional support will increase an artist’s prices, give them a wider audience and have them taken into a more serious context. But a lot of times that support is generated by leveraging clientele. The gallery will say there’s a waiting list for this artwork, but you can get it if you buy a second one and you donate that to a museum. That’s not very transparent; what we’re really trying to fight for at STP is that transparency. Because otherwise, the artists that you see in museums, the artists that you should praise or follow, it’s all been very heavily manipulated and I don’t think that is an honest way. I don’t think that’s really what the arts are about.

There seems to be a much greater scrutiny on big institutions and their practises right now than before. What do you think of this change in opinion to these big institutions?

During this whole racial pandemic a lot of the, how do I say, negligence taken by the institution and the gallery system has been spotlit and I don’t even think they’ve done a really great job of even trying to pretend like they care, which is not gonna go unseen. I think a lot of artists are seeing that, seeing how much the gallery system, the museum system, doesn’t necessarily support their cause. I think that’s a good separation to have because I think it gives institutions and gallery systems less power.

I was really surprised by a lot of the conflict caused by the last Whitney Biennial, but it was kind of like a lot of people having your cake and eating it too. A lot of artists who were selected to be in the exhibition, were in the exhibition, but then later on spoke up against the museum, and I think that’s a very calculated approach. If you really want to highlight some of those inequalities and some of those issues, then don’t be in the show, curated by the Whitney, and state why you’re not doing that. I think it’s a start, [but] it’s definitely happening all over.

In the seven or so years since you’ve made the Southampton Suite pieces, what would you say has changed most about you as an artist?

I think I definitely romanticise painting a lot more. My experiences with the art market and art world had created a jadedness and STP — and working with younger artists — gave me new hope. My interests don’t lie now with a painting or a sculpture, but more the opportunity that something like that can create. You know, a lot of the money I make from art, if anything, goes into STP and goes into great programming and being able to figure out how to get STP to support itself. I guess for me there was a point where I didn’t really believe that the work I was making was doing much for anybody else except for myself. I figured there was a point in my life where I could maybe take on something that had a more socially-conscious role.

You say that a lot of great artists don’t get recognition until late into their careers or even in their lifetimes. You’ve had yours so early on, allowing you to create STP. How do you feel about the success you quickly gathered upon graduation, and what do you think the effect of that has been on the work you make?

I think it has both its negative and positive effects. I think if I hadn’t gotten the recognition that I got early on, I probably would have developed into a much stronger studio artist. I would have had to work a little bit harder on my ideas and what I was doing. I guess the plus side of that was I was just given an amazing amount of resources and an audience to be able to carve out something that I believed in — maybe more than I believe in my own work. It’s really just circumstantial, but obviously I wouldn’t change anything now. Had I had to wait until my forties or fifties to really have my work taken seriously, I’m sure it would have matured a lot more, and been a lot stronger. I probably would’ve devoted my life to studio art. Whereas now, I am an artist, but I think a lot of my focus is in using the resources and the people I have around me to do something that I believe is a little bit more effective.

Southampton Suite is on view from August 2020 through January 2021 at the Parrish Art Museum.