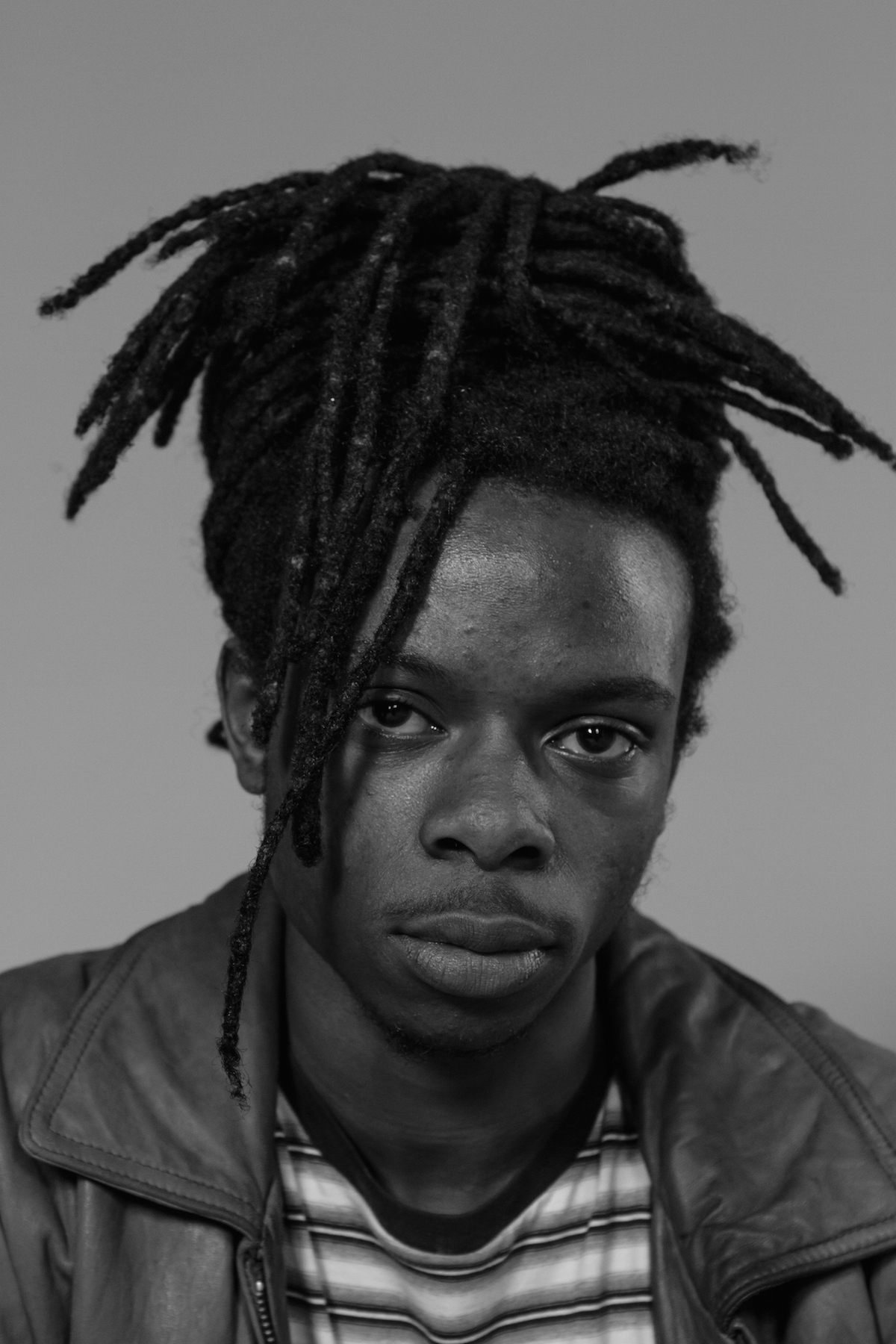

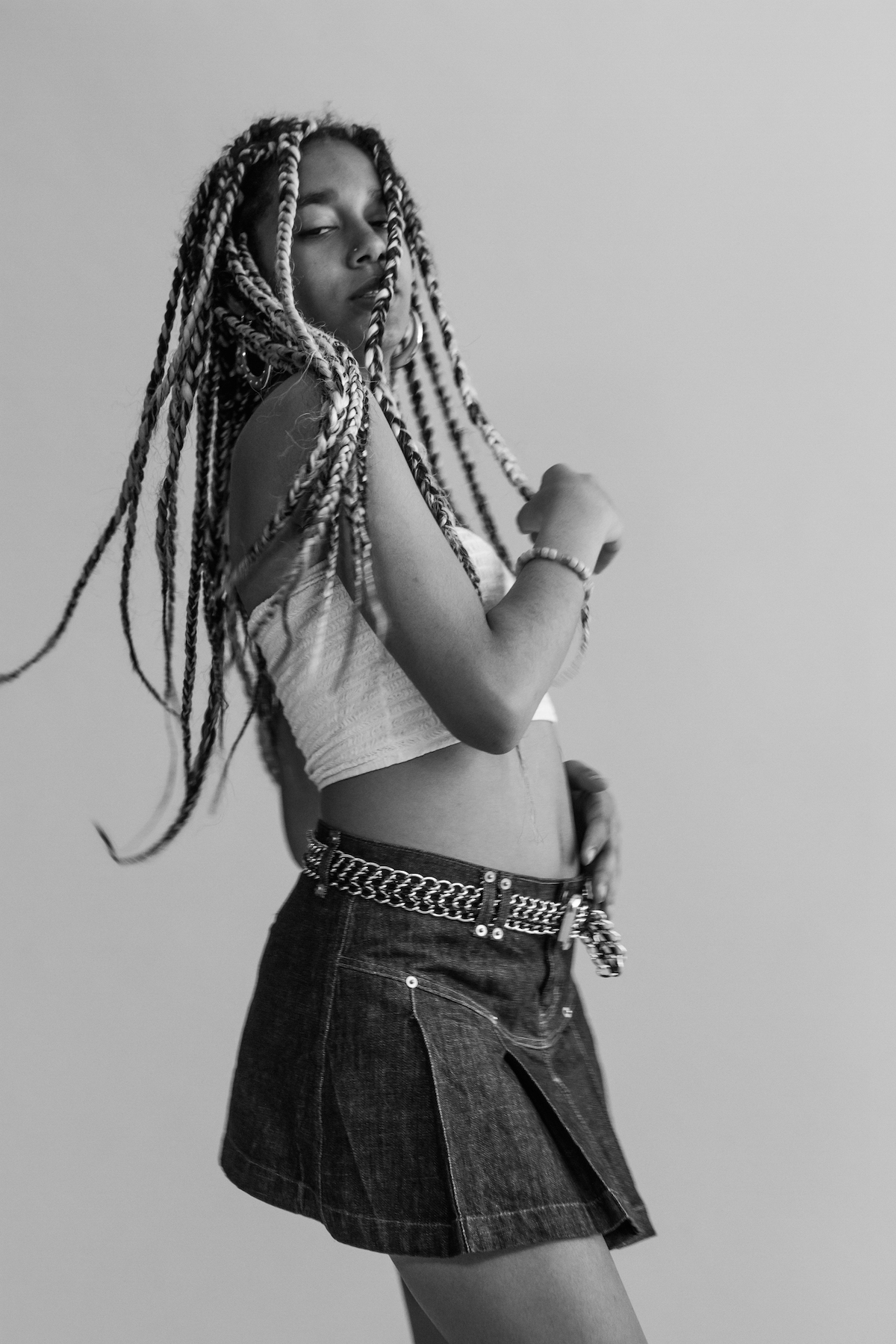

Lula Hyers, the 19-year-old Instagram star and artist, has invited me to Chelsea to check out her shoot of New York’s queer youth, and I’m 37 minutes late (weekend rail repairs, cab-less streets).

My last glimmer of hope, the one arguing that I’m not horribly late, dissolves when the guard outside the photography studio explains that kids — just like the ones waiting outside with long, tangled hair and skateboards — have been coming and going since the morning. Past the big black doors, I see that he’s right, that the space is full. There are snacks, drinks, Kanye singing out of the speakers, and a myriad of teens gathered in hoodied clusters.

Queer kids deal with more than straight kids, of course. But when you look at the numbers, New York is the gayest, queerest place to be — with more openly gay people than any other city in the US, and many more, and with greater density, than London. The stats imply that New York is a downy pillow on which all queers can rest their weary heads — including the young. There are so many queer-focused services for a kaleidoscopic community, and the annual Pride parade is one of the biggest cultural events of the year. There’s also a flourishing broader discourse around queerness in 2016, including voices like Rowan Blanchard and Jazz Jennings, that encourages all young people to define themselves by their terms, in their own time. Talking to the kids at Lula’s shoot, I first ask them if they identify as queer, and then a couple follow-up questions: When did you come out? Do you feel discriminated against as a queer person living in New York?

A girl named Jo with a sun-shaped afro greets me first, letting me know Lula is busy but will talk later. (I peer over the white room dividers and see Lula’s ponytail swishing as she snaps pictures of two boys smacking each other with roses from the floor, then hugging.) A boy and girl named Ben and Maria dip in. Ben rotates between pronouns because he’s a non-binary gay male, and Maria identifies as pansexual. They learned they were queer at different ages: he met a boy that he liked in sixth grade at summer camp and Maria fell for a friend in eighth grade; and none of their parents completely accept who they are, even in New York. Jo’s parents, both conservative Christians and Jamaican, taught her that it’s her responsibility to heal herself by uprooting corrupting demons. Maria admitted that her Russian-American mother is so homophobic, that she’d probably marry a man to “make life safer and simpler.” Ben’s parents are non-religious New Yorkers, and they’re content with his sexuality as long as he squeezes into binary, heteronormative roles: “Whenever I talk to them about gender issues, they always dismiss it like, ‘These crazy millennials!’ — like it’s a trend.”

The boys who fought with roses earlier now sit on the ground over bent legs, eating. Sebastian and Jonas are gay cisgender males who came out the exact same way — initially in fifth grade, when having a “crush” suddenly carried social significance. Sebastian began, “It’s very ongoing. You never stop coming out, or there is never really a coming out moment because it’s so fluid,” and Jonas interjected, ” I knew in fifth grade that I liked boys in skinny jeans more than girls, but it was never really a moment like: I know. It was a gradual process.” Sexuality is not a hat you jump out of bed, deciding to wear; it’s a natural stage of development that you grow into, with age, whether you’re queer or straight. “But every time I meet people there’s always this assumption that people are straight and that’s the norm.” So, throughout his life, he has to come out again, and again, and again.

Jonas, with quarter-sized eyes and soft cheeks, was teased as a kid for being who he is, despite all the anti-bullying legislation that passed in the state. “Our experience of being queer is subjective…. But I dunno, there are a lot of misconceptions about sexuality as if it defines someone’s character or interests.”

Ten minutes later, Ben swings back with some friends to talk about The Network, a city-wide group with a 999-strong Facebook following that offers queer youth in New York a chance to meet other queer youth. “First, it’s inclusive,” Ben says. “The media puts up these rigid narratives that are nothing like us, pretending it’s what it means to be queer, like the gay best friend… just throwing stereotypes around, but being queer is everything not straight: gay, lesbian, transgender, bisexual; and, we’re all in this together.” The Network meets up regularly in the apartment of any kid whose parents are happy to host over 60 teens in one night. “But it’s getting to be too much,” Ben admits, “We’re looking for a space.”

There’s a huge need for organizations like The Network because GSA — Gay Student Union or Gender Sexuality Alliance — isn’t enough for girls like McKenna, a bisexual high schooler with Cher-from-Clueless cuteness, who worries about coming out in school because “it feels like people will judge you.” “There’s not that many people who are out,” McKenna says, “The funny thing is I know a lot of queer people but I know only two who are openly queer in school.” Health classes don’t cover queer sexualities and genders, leaving students to find the information they need on the internet. Someone else pipes up, “Um, I’m 15 now? I was 13 when I came out and I say, ‘If you’re queer, go on Tumblr,’ because I still haven’t figured out.”

At queer-friendly spaces like The Network or Lula’s shoot, young people can open up about all their unique complexities, and daily challenges — like people who don’t believe in bisexuality. “A lot of people hate when people mention mono-sexual privilege, which is being attracted to only one gender,” says a girl named Avery, tucking her sky blue hair behind her ears. She’s still grappling with her bisexuality and how everyone views her because of it. “I feel like I’m going to mess up, or — oh shit! — fall into the slutty bisexual stereotype, and I’m scared to express my fears because I want to be confidently queer.” Sometimes straight guys belittle her and fetishize her identity; worse, other queers might accuse her of disingenuity, because “being bisexual means the option’s always there to cheat.”

It’s dangerous to argue that one kind of queer person is privileged, because all sorts face discrimination, as I’m continually reminded. But I hear repeatedly that queers of color battle darker issues than white queer people. Arahi’s friends with Avery and Ben and a part of The Network. She’s bisexual, too. “I hate getting my picture taken,” she says, hunching her shoulders, “but I noticed that Devon [a lesbian who’s unsure of her gender identity] is often the sole Asian that shows up [to queer events]. I have a lot of friends who are queer and white and are accepted but when I talk to my mom, who’s Japanese, she tells me being bisexual is a phase. And back in Tokyo, I’m sort of alienated as the girl who went wild in America and that I’m white-washed.” According to Arahi, Japan favors conformity over all else; since being queer is considered different, it’s taboo to even discuss. “My friends from back home don’t even invite me over.”

Lula joins the conversation as everyone begins talking about all the other things that make them who they are: some are artists, actresses, and music producers. Ben’s attending a magnet school and can’t wait to leave for college in the fall. Avery quips, “I’m just fun.”

Lula, like Maria, identifies as pansexual. When she came out in high school — a teacher encouraged everyone who wasn’t straight to come forward in class and Lula stepped up — she called herself bi, but then “felt that was a false representation because that meant I believe there are only two genders. Pan suits me because right now; I’m attracted to all people.” Like this event, it’s about breaking free of the heteronormative, the gendered seesaw, and the slotting of queer identities into neat cubbyholes: gay, lesbian, bisexual.

Lula paid for the studio herself, only asking her subjects to bring food to share, and there were tables’ full. To her, being queer is an identity that joins her to a movement.

“Heteronormativity is a plague,” she says. “At times I’m privileged to walk down the street and pass as a heteronormative woman, and not be harassed… but queer kids do experience violence.” The beauty of queerness, according to Lula, is supporting each other through all of that.

“It’s beautiful that kids are accepting themselves younger and younger [she hates the phrase coming out the closet because it implies that there’s something to be ashamed of] and finding community, because that means the movement is getting stronger.” And, that’s what this photoshoot is about.

Even in the Western mecca of queer culture, New York City, kids get caught in a labyrinth of potential adolescent pitfalls and identity-shame: bullying, queer-phobia, peer judgement. Lula describes her first lunch with her first real girlfriend as gutting. She worried that people would say she was queer even though she is queer. If her health class was queer-friendly (instead of leaving her to the Internet) and her English class included books with queer characters, she might have known how to accept herself.

Queer kids need community support and accurate representations of people like them as guides because queerness shapeshifts the world around you. While our predominantly binary-locked world sees everything as one or the other, male or female, to be queer means living in an explosion of other colors. Leaving the studio, I feel a shift from a lighter, looser energy to something stagnant and congested.

“This project was made for queer youth.” Lula asserts. “Yes, it might help other people to understand queerness but this is about representation and celebration for us, by us.”

Lula takes scores of selfies for her popular Instagram account, so I ask what a self-portrait of her own queerness would look like. She describes herself arranged in some weird position, switching through an array of crazy outfits — “because I love to dress up,” she says, as if to show off each lovely facet of her identity.

To participate in the project, and for more information, visit Lula’s Instagram.

Credits

Text Kristin Huggins

Photography Lula Hyers