This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Summer! Issue, no. 372, Summer 2023. Order your copy here.

It’s the day before staging the Marni show in Japan – the second chapter in a pair of travelling shows, starting in New York and ending in Tokyo with global ‘activations’ along the way – and, when I arrive to speak to Francesco Risso, he seems to be meditating. He’s sitting, totally still, in a stark white room within the main chamber of the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, the geometric sports venue built by the architect Kenzō Tange for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics: his signature bleached curls are freshly shorn, his demeanour zen and his typically colourful wardrobe swapped out for an all-white outfit made predominantly of paper. It’s eccentric, to say the least. Someone had whispered to me earlier that he flew his shaman out from Bali to be on hand for the show prep. Is he OK?

“Exercising control and rhythm,” was how he described his state. “It’s about finding a rhythm between something that feels quite rigorous and creativity,” he expanded. “A rigour that feels delicate, reflective, and makes you think; a creativity that feels comforting and not just made for the algorithm.” Having recently read Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention, which explores how our brains are overloaded with information in modern society, Francesco was thinking about precision, discipline and focus – all typically Japanese virtues. During the pandemic, he learned to play the cello, a hobby that reminded him how much diligence it takes to get better at a chosen métier. And, like all of us, he is increasingly fed up with the gimmicks and distractions we are bombarded by in the fashion landscape, often as a decoy from what really matters: the clothes. “I’ve been struggling with this imprisoning algorithm, which is harsh and brutal,” he huffed, slightly worn out. “I think what we’ve been working on, gradually, is about really trying to have a dialogue with what we make – which, to me, is the thing that I love the most.”

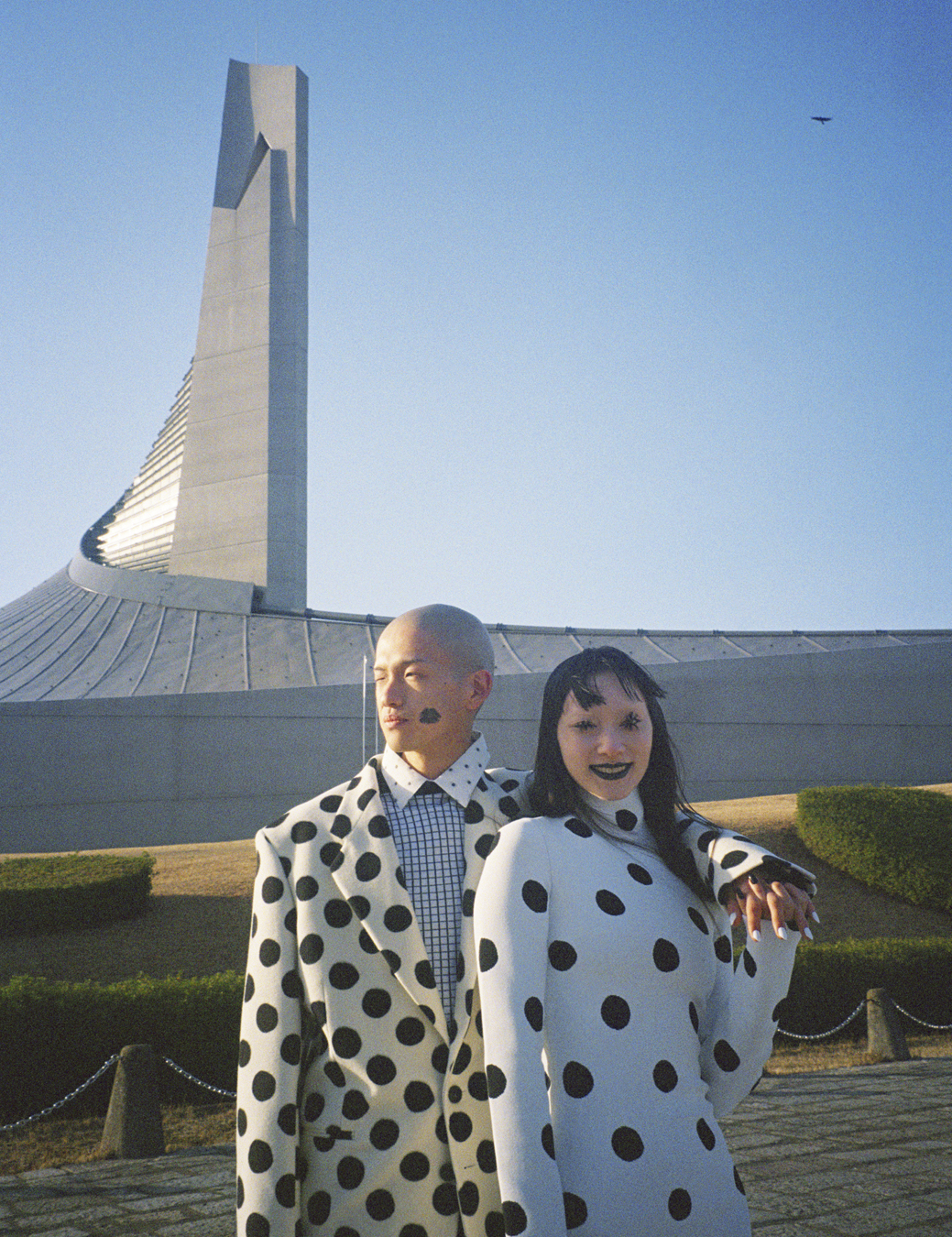

The show he presented the next day was a radical departure from the blueprint he had set for Marni in 2016: ethereal and hand-painted, upcycled and chaotic, a sort of bohemian love affair between romance and decay. This was remarkably calm: the vast show arena was entirely wrapped in crisp white paper, the centrepiece of which was the Tokyo Chamber Orchestra wearing the same white paper pyjamas as Francesco. Marni’s musical director, Devonté Hynes, scored the soundtrack, which kicked off with the dramatic banging of drums. Then, the predominantly street-cast models appeared in a collection that signified carte blanche: a sharpened focus on graphic, direct clothes with a juxtaposition of polka dots and bulbous silhouettes in four key colours – red, yellow, white and black. Clean direct, and comprehensive. It also felt more grown-up, a classic wardrobe of serious clothes, from beautiful Crombie coats to neat shift dresses; buttoned-up shirts down to ladylike pumps; LBDs, scarves and two-pieces. Often proportions were exaggerated, blown up into bubbled, chubby shapes courtesy of padding (and a collaboration with young Chinese designer Ding Yun Zhang), but then shown alongside mod-ish svelte dresses and tailoring.

The end result felt like a childlike idea of grown-up clothes – almost like cartoons. Against the white paper set, and in front of an audience of almost 2000 people (many seats were made available to students and the public), the clothes stood out for their starkness and singularity, like manga on the page, the flatness of Hokusai, or even Takashi Murakami’s Superflat art movement.

So, why Japan? Francesco wanted to connect with the community of like-minded creatives here who were sequestered from the rest of the world during the pandemic – but also because he found that the discipline and clean rigour of Japanese art, architecture and culture spoke to his new mood. The country was also home to the very first global outpost of Marni in the late 90s, and still accounts for 23 percent of its sales: not to mention the brand’s highly successful collaboration with Uniqlo, which perhaps also served as a lesson in how to communicate an aesthetic message to a wider audience.

The collection Francesco showed in Tokyo seemed to signal a kind of reset, chiming with a wider call in the fashion world for less gimmick, more substance. Arguably, it began with Marni’s previous show in New York, which saw a more graphic sensibility and marked the first time Francesco worked with i-D’s fashion director Carlos Nazario, who styled the show. “I think we are overloaded by information and wanting to influence people to be a bit more contained or bring some clarity,” Francesco reflects a couple of months later. Now, we are sitting in his book-lined office in Milan, an antique Olivetti typewriter at his desk and worldly curiosities scattered around him – a stark contrast to the clinical minimalism of his Tokyo set-up. ‘Marni’ is scribbled on a raw-bricked wall, just like the hand-drawn branding on his collections. “I think we miss clarity in the world right now: everything feels so scattered and so chopped up.”

Designers are often directed by personal whims that swing in the direction of an unfixed pendulum, but something about Francesco’s demeanour suggests this move has been a long time coming. You could say the seeds for change were planted during the pandemic, when he blazed a trail in how he presented Marni’s collections, namely by working with creatives from around the world – Sasha Lane, Crystallmess, Paloma Elsesser, Yves Tumor, Deem Spencer, Szela, Mykki Blanco, Mimi Xiu and Moses Sumney, to name a few. They were invited to photograph themselves in the clothes while making art in their homes, offering a platform for their work at a time when galleries, music venues and indeed fashion shows were on pause.

That work evolved into a wider tapestry that Francesco coined “the Marnifesto” – orchestrated with the help of creative consultant Babak Radboy, best known for his work with Telfar in New York – which offered a sense of individualism and reality to the off-kilter, quirky clothes that Marni had been showing for a few years. It made them make sense in the real world; Francesco’s hand-painted, rag-tag designs – known for their raw edges, exposed seams, preloved fabrics, and kindergarten craftiness – were recontextualised as joyful expressions of radical individualism at a time when everything seemed uncertain and the world was demanding more from fashion houses.

“It really was a moment for us to regain and strengthen that unity, and to think about it going beyond these walls, you know,” Francesco reflects. “There was a necessity of bandying together.” Post-pandemic, the spirit of the community didn’t leave him. Though he jokes that, at this point, the word ‘community’ has been turned into marketing jargon, he laid the groundwork for several one-off projects at Marni including capsule collaborations with Paloma Elsesser and Erykah Badu, as well as unconventional campaigns around its partnerships with Uniqlo, Carhartt WIP and even Serax, the Belgian interiors label. Often, Francesco’s creative process starts with group discussions among friends and the Marni studio, an antidote to the pyramidal, egocentric dynamic between creative directors and their employees. “I would say that more than community, what really creates value is this living interaction,” Francesco explains. “That’s what really makes me feel alive. The work that I do, I don’t think I would be able to do it differently. It’s a collective work and I get joy from that because there’s a continuous curve of learning, you know? It’s not that way of working where we just take an artist’s work and Photoshop it onto a piece of clothing. It’s part of a long, long conversation of working together and experiencing each other. It’s almost like diving into each other’s hands.”

Francesco’s upbringing does a lot to explain his approach. Born on New Year’s Eve on a sailboat just off the coast of Sardinia – during a stint in which his father moved the family to sea – Francesco had an eccentric childhood, the youngest of a Von Trapp clan of several children with different sets of parents and grandparents. Eventually, they all ended up living together on land at his father’s pile in Genoa, during which Francesco describes himself as being constantly in “observation mode”. “There was a point when we were all living together and it was literally like a crazy commune,” he laughs. “Being very young, I was kind of silenced by these very loud characters.”

You can see how it informed his current status as a ringleader for a global group of freewheeling creatives. A childhood spent getting into trouble for taking scissors to his relatives’ clothes was a clear signal for a career in fashion. At sixteen, Francesco moved to Florence where he enrolled at Polimoda, then transferred to FIT in New York, before completing his studies on the MA course at Central Saint Martins in London under the notorious star-maker Professor Louise Wilson. “I came from New York and had a weird American accent because I learned my English there. She didn’t like that at all,” he recalls. Soon, he was scouted by Blumarine and moved back to Italy, before landing a job at Prada where he would spend a decade – that he describes as one of the brand’s most creative – before emerging from the shadows to the driver’s seat of Marni in 2016.

The formidable women he was mentored by – Louise, Mrs Prada, and Anna Molinari – coloured his approach to design. “Louise didn’t want you to make fashion until you had developed your creativity around any object, any possible inspiration, for a big amount of time so that you would build this innate curiosity for how something is made from every perspective, without immediately having to translate it into fashion,” he remembers. “Mrs Prada had this capability of really understanding the world, culture and humanity, and we would often have dialogues around an idea for months, and then the collection would be made in a week,” he marvels. From her, he also learned the importance of merchandising. “She had an understanding that you have to express the idea and there is a balance between creativity and product, which has always been her thing: you have to have the clothes on the streets, not just hanging there in a boutique.”

This is why you’ll find shoppers flocking to Marni stores for furry sliders, accordion-like leather bags, and striped mohair sweaters – even if they’re often sidenotes to the more directional pieces on the catwalk. When he first joined, he was careful not to follow what he calls “the Prada recipe”, instead choosing to emphasise rawness and upcycling. Often his kooky, DIY designs were made in his image, which at various times has included a painted face, talismanic jewellery, Liberty-spiked hair, vintage fur hats and patchworked shirts. Truth be told, it took a while for his rebrand of Marni – founded in 1994 by Consuelo Castiglioni as an offshoot of her family’s fur business that quickly became known for its bold prints, eclectic colours and chunky accessories beloved by art-world types – to get off the ground.

Consuelo exited the brand in 2013, after a majority stake was acquired by Italian businessman Renzo Rosso. It is now a part of Only The Brave, a mini conglomerate of fashion houses that now includes Diesel, Maison Margiela, Viktor & Rolf and, most recently, Jil Sander. Luckily, Renzo allowed Francesco ample time to develop his vision, and even evolve it. Some of his shows have been so out there that clothes have been intentionally falling apart as they traipse through dimly-lit warehouses with standing audiences. In 2021, he staged a show in which he not only dressed models but the entire audience, with each guest individually fitted in the ateliers in hand-painted deadstock clothes from the archives. “I remember people would come to me and say about the hand-painted pieces: ‘Oh, you’re not going to be able to sell this!’” he smiles. “But actually, we made a structure where the hand painting became a part of our mechanics, and the capabilities of what we can do with craft were huge. Every piece has the mark of a hand.”

You may be asking: where does that sentiment sit within the graphic new direction of Marni, all monochrome polka dots and straight lines? Well, it’s still there. Look closely and you’ll notice that the ostensibly sharp, high-waisted trousers are actually knitted; the classic coats given glitched Op Art checks; the accessories and clothes carefully mismatched to appear ever-so-slightly trippy. “It’s funny because everyone was asking about the hand paint and where it’s gone, because it has become such a part of what we do here,” Francesco says of the collection. “But actually, it is there – every dot, every check, every straight line was hand painted, but in a much more subtle way. It was not necessarily immediately visible to the eye.”

It goes back to that book he had just finished reading: Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention. In our attention-deficit age of speed-scrolling, Francesco just wants you to look a bit closer and really pay attention to the clothes. There is, in the most minute of details, still plenty to discover at Marni.

Credits

Photography Fumiko Imano

Fashion director Carlos Nazario

Hair Holli Smith at Art Partner

Make-up Yadim at Art Partner

Fashion assistance Loreto Mancini

Hair assistance Sayaka Otama and Cindy Kamtche

Make-up assistance Paloma Romo and Joseph Rios

Casting Midland and Bobbie Tanabe (HYPE)

Models Fumiya Imabashi, Seidai Fujii, Jeff Zotorvi and Shunsuke Sano at Exiles, Kai Newman at The Society, Saki Nakashima and Mona Kawasaki at Tomorrow Tokyo, Serena Motola at Box Corporation, Hayato Kurihara at Stanford, Nina Utashiro at Far East, Saunders at Premier, Yihan Zhang at Wizard, Nodoka Usami at Unknown, Efron Danzig at Midland, Paloma Elsesser at IMG, Giorgio Galgano at Persona, Elina Zhuravleva at Magma Tokyo, Hoshi Hijikata, Riku Furuta, Kadeem Spencer and Isami Nasu

All clothing and accessories MARNI AW23