The portraiture work of American photographer Mary Ellen Mark centred on inclusion, trust and intimacy. Her personal contact with her subjects, mostly marginalised women, had a lasting impression on her. In her lifetime, Mary revisited the people who appeared in front of her camera time and time again. She once said: “Every photographic project that I have produced lives with me forever.”

Mary, who passed away in 2015, left behind a diverse body of images. While she worked as a unit photographer on film sets like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Apocalypse Now, but was predominantly known for her personal projects. In Ward 81, she photographed women in a psychiatric hospital. Falkland Road saw her spend time with sex workers in Mumbai. Meanwhile, her critically acclaimed series Streetwise saw Mary capture photographs of the children she befriended, ones who lived on the streets of Seattle. It was this connection to her protagonists that set her apart from her contemporaries. She took a deep dive into getting to know them by visiting them repeatedly over her career and, in the case of Ward 81, living next to them. Mary stayed in Ward 11; only a door stood between her and the women she lensed.

Works from these series — as well as a handful of others, among them Mother Teresa’s Missions of Charity and Indian Circus — make up Mary Ellen Mark: Encounters at C/O Berlin, the first major retrospective of her work, co-curated by Sophia Greiff and Melissa Harris with participation from the Mary Ellen Mark Foundation. “In German, we have this term, ‘helicopter journalism’,” Sophia says. “Journalists fly into a faraway region, approach communities that they themselves are not necessarily familiar with, take photos and leave.” But what Mary did was different, she says. “She had this immersive strategy. By spending time with the people, she got to know them, and they got to know her and trusted her. If they would not have accepted, she would not have had access.’’

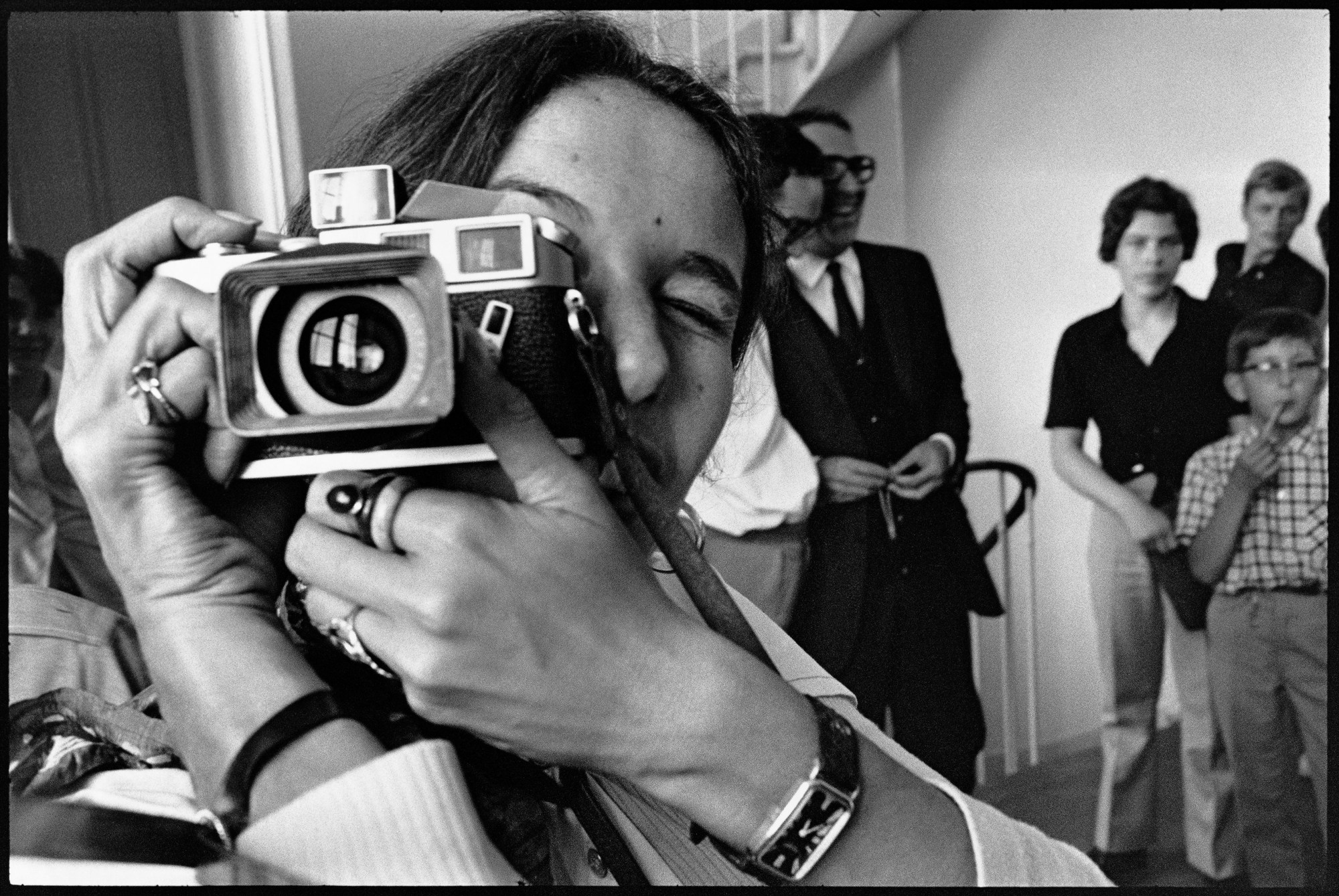

Mary often plunged herself into her work, blurring the lines between photographer and subject and underlining her closeness to the individuals she shot. She managed to be invisible yet obviously present as she stood behind her lens, wanting to embrace more of an active approach to her art. “I don’t want to be an illustrator… I want to have a chance to be a real part of the creative process and not just a technician who clicks the camera.” She expressed this sentiment later in her career as she became disenchanted with her magazine commissions and their specific notes on what she should photograph. Mary preferred her own method of social documentation: she got so close that the casual observer could notice it in her prints.

In Streetwise, for example, Erin Charles (also known by her nickname Tiny) stares intensely at the lens in her Halloween costume in a black-and-white portrait. This initial photograph was the beginning of a long relationship: Mary continued to visit Tiny and, later, her ten children, over the three subsequent decades after that first meeting in Seattle.

This was a common occurrence for Mary: she visited India in the late 60s to create the images that would become Falkland Road. A group of women working at a brothel caught her attention, and though they pushed her away initially, she came back 10 years later. She stuck around until they became fascinated by her. Eventually, they gave Mary permission to take their photograph, and she stayed there for three months. “It was something about her personality, her character, that showed people she was interested,” Sophia says. “That it was about understanding and not [just] having a good story she could sell to magazines.’’

Mary was born in Philadelphia in 1940 and earned degrees in art history, painting and photojournalism from the University of Pennsylvania. She spoke of using a camera for the first time as a sort of epiphany: “When I became interested in photography, which was in 1963, I didn’t think: ‘Should I do still-life photography? Should I be a landscape photographer? Or should I do commercial work?’ I knew that I wanted to photograph people, and I wanted to do documentary essays on social situations.”

In the late 60s and early 70s, she covered a range of news stories, from the civil war in Bangladesh to drug users in Britain. Later, themes relating to women kept appearing in her portfolio: pregnancy, motherhood and prostitution. Melissa Harris wrote about the social climate Mary captured in the eponymous book accompanying Encounters: “Coming of age at the apogee of feminism,” she said, “it is no wonder, perhaps, that she so often turned her gaze to women and girls.”

In her obituary, a journalist for the New York Times reiterated the time she had told the New York Times Magazine that “she had two main ambitions in high school: to become the head cheerleader and to be popular with boys.” The journalist added: “She succeeded at both.’’ Though those on society’s fringes were her main subject, she also dedicated time to photographing the classic high school experiences, like prom. What’s striking about the cross-section of Mary’s subjects is the sympathetic understanding with which she approaches everyone.

’’The title Encounters says it quite well,’’ Sophia says. ‘’[Mary] has said that she wanted her photographs to be about the basic emotions and feelings we all experience. I hope when visitors leave the exhibition, they have this feeling. Maybe we’re all not that different. I could have been them. They could have been me.’’

C/O Berlin presents the retrospective ‘Mary Ellen Mark: Encounters’ from 16 September 2023 until 18 January 2024.

Credits

All images © Mary Ellen Mark, Courtesy of The Mary Ellen Mark Foundation and Howard Greenberg Gallery