As quickly as Masahisa Fukase found new subjects to shoot, he lost them. As if by a process of elimination, the Japanese photographer ended up being his only subject. In 1989, at the age of 55, Masahisa began travelling through new and familiar landscapes, documenting himself as a strange shadow-presence intruding into the frame. In 1992, these snapshots found their way onto the black walls of Ginza Nikon Salon in Tokyo, where Masahisa staged a flabbergasting show consisting of 444 overlapped proto-selfies — or, as he called them, “piles of tombstones”. A few months later, Masahisa, blind drunk, tumbled down the stairs of his favourite haunt and spent the next — and final — 20 years of his life in a coma.

“That final exhibition was an extravagant photographic funeral which Masahisa organised for himself,” explains Tomo Kosuga, the founder of the Masahisa Fukase Archives. “Having fired at those close to him in the name of photography, he finally turned the barrel of the gun on himself.” Masahisa’s biography was in constant crossover with his photography — an extraordinary visual narrative chronicling his most private memories, moments and relationships. “His work is essentially a reflection of his life,” says Tomo.

Born in the town of Hokkaido in 1934, Masahisa was the son of a successful local studio photographer. He moved to Tokyo in the 50s, and began increasingly exhibiting and publishing his own photography. In 1974, he co-founded the Workshop Photography School with Shomei Tomatsu, Eikoh Hosoe, Nobuyoshi Araki and Daido Moriyama, all of whom were included in a milestone MoMA exhibition that same year, catapulting Japanese photography onto an international stage. “What distinguished Masahisa from the rest, in my opinion, was his utter dedication to photographing everything through himself,” explains Tomo, who has just co-curated Masahisa’s first Japanese retrospective, now up at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum. Consisting of eight chapters and 117 works, it lays out the life and work of the polymorphous genius.

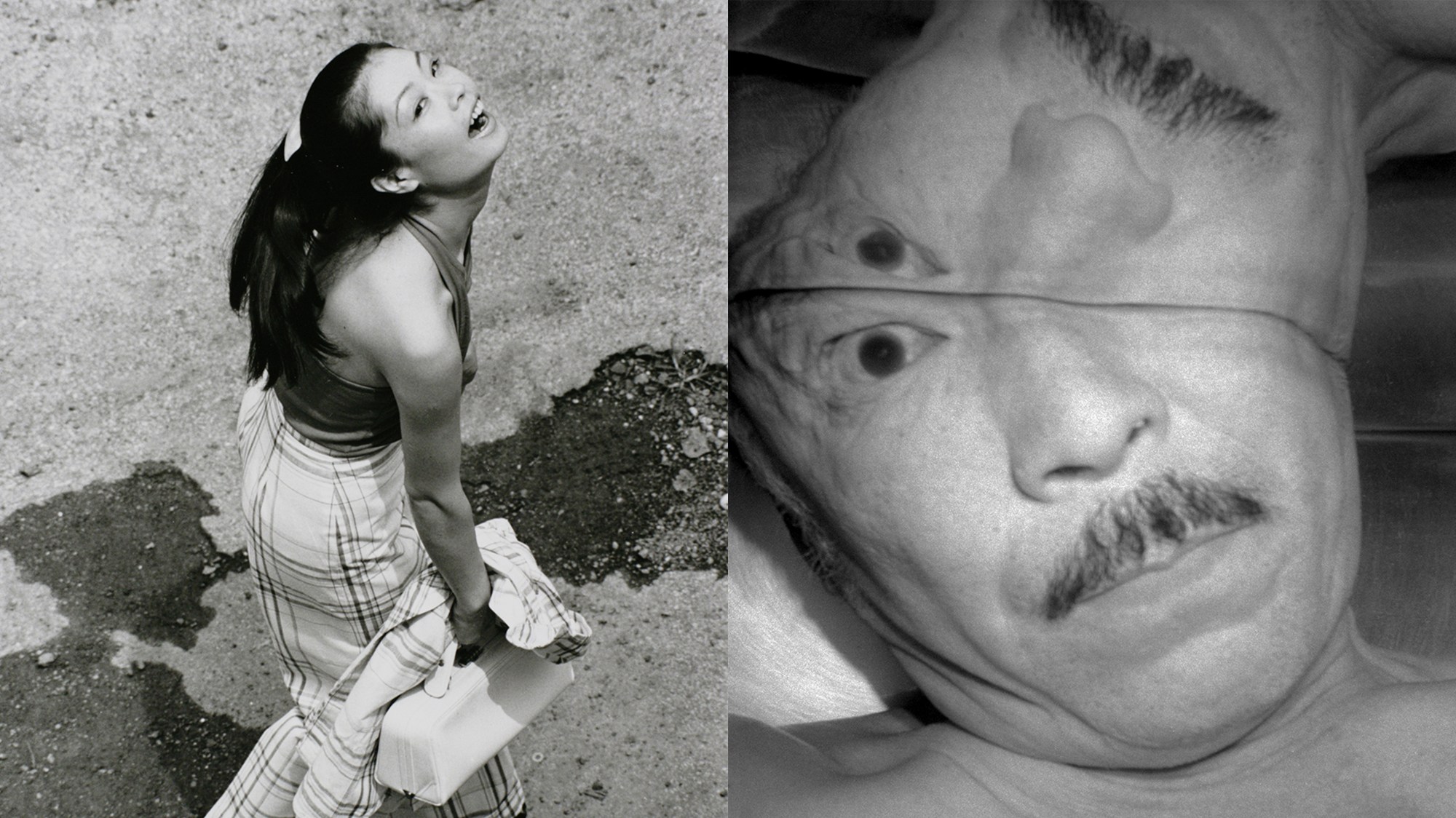

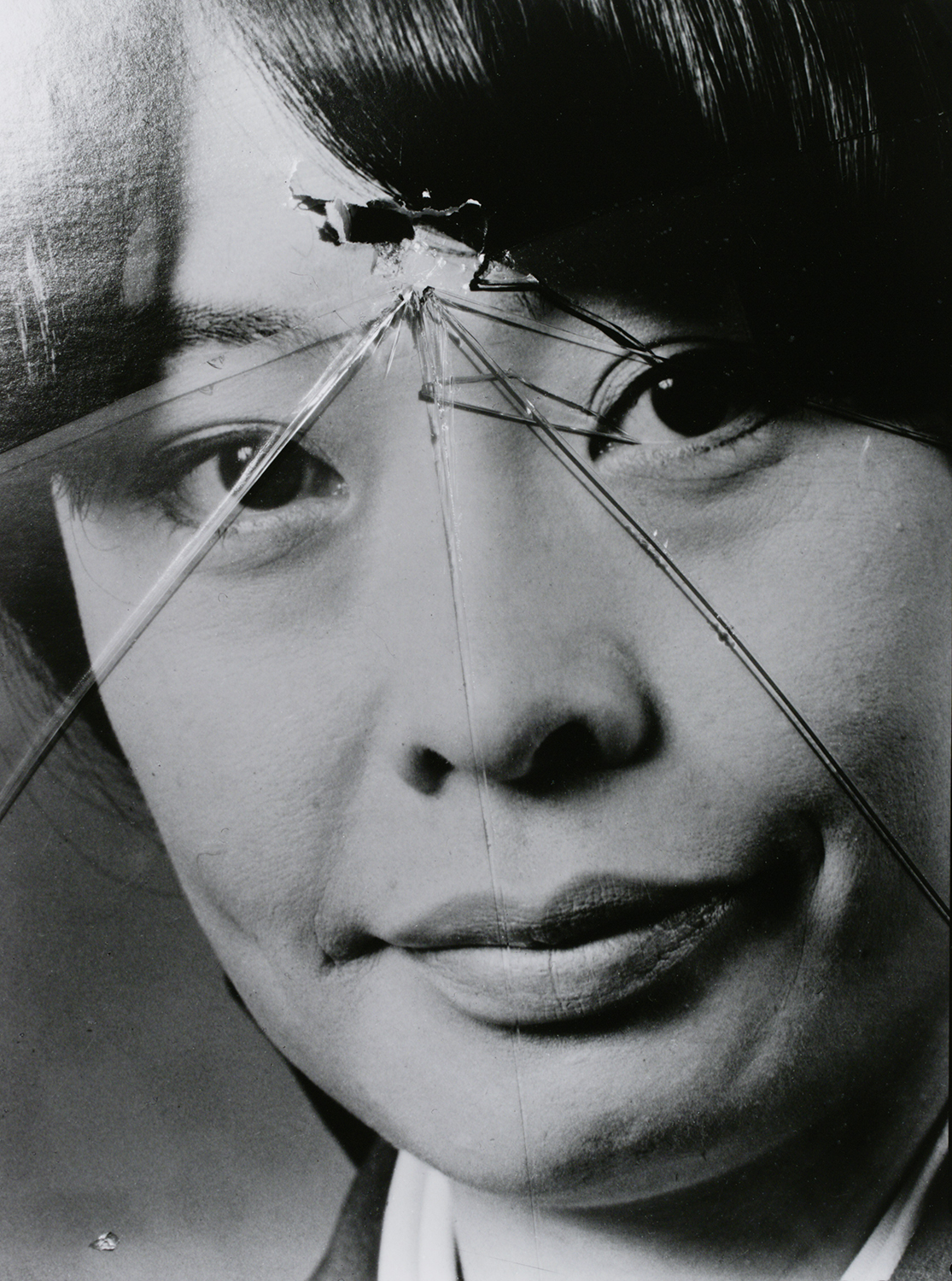

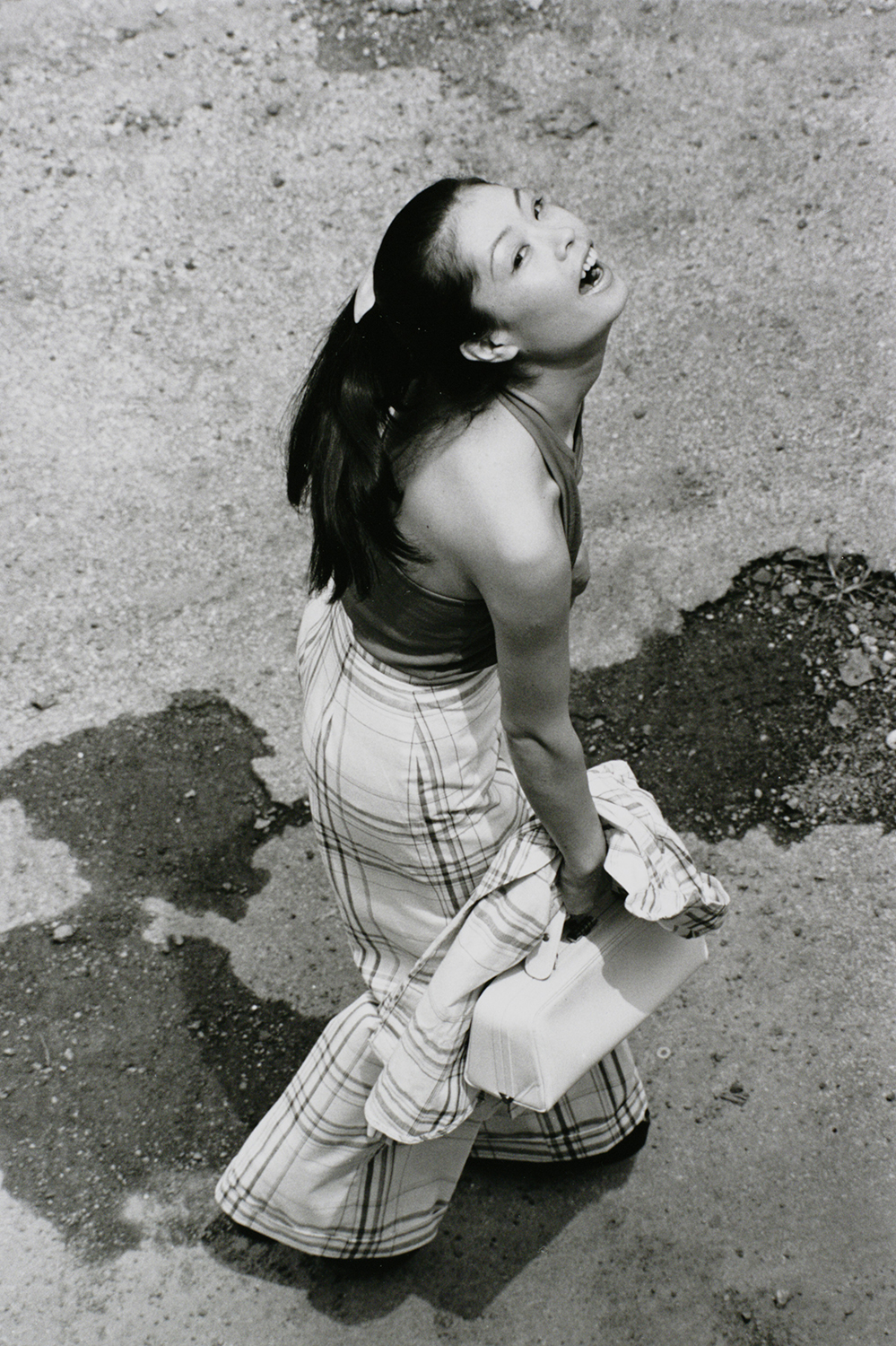

Masahisa’s first great subject was his wife and muse, Yōko. She fell into his life following the disappearance of his former partner, Yukiyo. Both women appear in Masahisa’s first book Yugi (Homo Ludence) (1971), a turbulent meditation on the interconnected forces of life and death. “The oeuvre of Masahisa would look very different if he never met Yōko,” Tomo says. “Their relationship was intense and difficult.” Yōko would later star in From Window (1973), a series in which she squirms, shouts and sticks her tongue out at Masahisa, who photographed her leaving for work each morning with a telephoto lens. Their games turned their private lives into art, leading to a paradox in which they appeared to be together solely for the purpose of Masahisa’s obsessions. “His desire to superimpose himself onto Yōko was so great that it drove her to the point of mental exhaustion,” explains Tomo. “After 13 years, she left.”

Yōko’s termination of their marriage plunged Masahisa into a dark, alcohol-fuelled depression. He returned to his native village — the very source of his being — and chased down the ravens that flocked the grey bowl of sky overhead. The photographs he took are imbued with a hair-raising dread, projecting the solitary soul of a man who had careened into a compulsive artistic practice which bordered on the edge of madness. What followed was Ravens (1986), hailed as the greatest photo book of all time.

“You really get a sense of Masahisa’s self-identification with the ravens, whose ink-black forms seem to possess the shadow of Yōko,” Tomo says. “Masahisa became the sole raven frozen by his camera and immortalised on the book cover.” With Ravens, we are no doubt dealing with the most sorrowful set of photographs ever made. However, Tomo is keen to remind audiences that Masahisa had a sunnier disposition too. “Masahisa was a self-confessed cat lover, and turned to them with greater intensity following his divorce. He said he trusted cats, not humans, and his unique brand of feline photography reflects his joyful side.”

If Masahisa’s moody corvids represented love lost, his cats represented love regained. The story goes like this… In the summer of 1977, Masahisa was gifted a calico kitty, who he named Sasuke. Soon afterwards, Sasuke — you guessed it — disappeared. Heartbroken, Masahisa pasted “missing cat” posters all around town, scouting the side streets day and night until he fortuitously found a lookalike (or reincarnated) Sasuke. Masahisa took him in and chronicled their rollercoaster friendship in Viva! Sasuke (1978), a flawless feline collection in which you can basically feel Sasuke’s whiskers tickling your face. Uninterested in the “cuteness” of cats, Masahisa possessed a profound feline affinity, later confessing that he felt himself “becoming” a pussycat. If that wasn’t enough, Masahisa would go on to snap himself touching tongues with people in bars around Shinjuku one year before his fatal fall. “The tongue is an extremely powerful sensual organ,” he declared.

For Masahisa, taking photographs was an expression of love for his subject. From the 70s onwards, Masahisa began to reflect on his roots and the work of his father and grandfather, both of whom had been photographic technicians. “Masahisa incorporated traditional artisan craftsmanship with a contemporary approach,” Tomo explains. These pursuits materialised in his book Family (1991), a playful parody of the family portrait. Across two decades, the Fukase family is pictured against the same white backdrop, growing up and growing old. “In the end, Masahisa’s father dies, signalling the death of the family unit,” Tomo says. “It is a memento mori. Masahisa was always committed to living through the thought of death.”

With Family, Masahisa produced a peerless masterpiece, but it wasn’t his last. In 1991, he turned the camera on himself for the final time, and he did it in the bathtub. “Anyone can easily take a self-portrait today, but I believe Masahisa demonstrated this act in the realm of art,” says Tomo, who draws a connection between Masahisa’s poignant underwater selfies and his 1964 film of Yōko goofing around in the sea. “We can see an afterimage of Yōko in the bathtub series,” he explains. “Masahisa ultimately photographed himself by replacing himself with his subject, in turn superimposing his true self.”

“Where am I? Who am I?” Masahisa asked in a diary-like text stuck on the walls of his final exhibition. “One might think that wanting to make people ill at ease by exhibiting my face with unpleasant expressions derives from a form of sadism, but let us not forget that, originally, sadism and masochism were two sides of the same coin, as were genius and madness.”

Distinguishing the genius and the madness of Masahisa is tempting but futile. Here was a man who saw his life almost entirely through his lens, finding fragments of himself in everything he loved and lost. It is hard to disagree with his wife Yōko, who tagged him the “incurable egoist”. Then again, to have “cured” him would have been a real pity indeed.

‘Masahisa Fukase: 1961—1991, Retrospective’ runs at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum until 4 June 2023.

Credits

All images courtesy of the Masahisa Fukase Archives, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum and Michael Hoppen Gallery.