“Everybody wants to be black.” You often hear this from young people in the Brazilian art scene, who seek both to claim legitimacy (45% of the population of Brazil is black or brown) and to protest the appropriation of African diaspora culture. Thanks to the internet, we’ve witnessed the birth of a pan-African movement in art, politics, and culture, which has helped us to rethink aesthetics and embrace our roots.

Gen Z’s digital afrofuturism plays an important role in reversing the whitewashing of Brazil, and the rebirth of a genuinely Brazilian art scene influenced by black history. The cosmopolitan cities of the South-East, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro grab the most attention globally. But it’s in small cities that we find the most avant-garde work, much of it made by queer youth. It connects with nature, ancestral spiritual life, and inherited wisdom to reflect the now, and foretell the future: one without fear.

i-D talked to three young people who were born and live outside the country’s big cities, and produce contemporary Brazilian art.

Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro, 22, artist, researcher and psychology student. Vitória, Espírito Santo.

Please describe your work.

I investigate how the violence created during slavery built a genocidal nation. I study the processes of colonization of African countries and its unfolding in Brazilian territory, making my body the main focus of these works through performance and photography.

What is your creative process?

In my “Body-Flower” project I present an anatomy that enables plants to be born throughout the body. Medicinal plants, used for healing, and also poisonous plants, used for cruelty. Plants of blessing, wizardry, sorcery, and witchcraft.

You are far from the cosmopolitan axis of contemporary art. How does that manifest in your work?

I live in a state ignored by national policies to encourage art. Here, there are few commercial galleries. There are few opportunities. I’ve heard from art teachers, “In Vitória there are no artists.” They said to me, “Who do these gays think they are? They will never leave Vitória.” In the last year, I have preferred to create installation works and I realize that this desire is a response to my intention to live in a safe place for myself.

Instagram is your main form of exposure. What are the advantages and disadvantages of internet art?

The advantage of the internet is that I can expand my network of friends, and the disadvantage is that I intensify my vulnerability. The more people know about my existence and work, the more vulnerable I become.

There are very strong spiritual and mythical themes in your work. Where do you think this comes from?

I’m a witch, I’m an enchantress, I’ve done capoeira, I’ve been part of a congo band, I’m a member of the community of the oldest samba school in Vitória. “Body-Flower” is me and all those people who have unlearned the institutionalized ways of using our limbs, organs, and cavities.

How do you see contemporary Brazilian art?

There is no novelty in contemporary Brazilian art, but rather continuity, improvement, upgrades of hierarchical systems and emancipation practices. So I understand contemporary art as a symptom of a society that is sick.

Davi de Jesus, 21, visual artist and performer. Pirapora, Minas Gerais.

Please describe your work.

Conceived on the banks of the São Francisco River, I work documenting riverside ancestry and perceiving “almost rivers” in the arid landscape. One of my greatest interests for painting is the earth, the initial mother. In photography I use the body as a measuring instrument of the world. An aquatic, muddy and silent nature that can be read as a bait, fish or stone.

Describe your creative process.

I work in several mediums: photography, painting, drawing, object-sculpture, performance, and text. After my mother’s death, I inherited the family’s analog photographs, and worked on curating the records which documented our riverside daily life.

What are your main childhood memories and how do you believe they affect your work?

I come from a family of washerwomen, fishermen, carpenters, and carranqueiro masters. I grew up bathing in the raging waters of a mythical river. “Barranqueiro” is the name given to the riverside population of São Francisco. I am a “Barranqueiro” and everything that I create is part of the experience in the backyards, camps and fisheries. When the river rose, it flooded my family’s house and a sucuri snake broke my neighbor’s arm in front of me.

Instagram is the main tool of exposure of your work. In your opinion, what are the advantages and disadvantages of art on the internet?

The advantage is in the ease of drawing people’s attention to my work. I like being able to be ephemeral too. The discomfort may lie in having to post what I build so quickly before it matures.

There are very strong spiritual and mythical aspects to your work. Where do you think this manifestation comes from?

A great part of this manifestation in my work comes from the carrancas — figureheads that adorned the front of the boats of the São Francisco River, with the purpose of opening the way, protecting and attracting fish. They warned when the vessel was at risk of shipwreck, by moaning loudly three times.

How do you see the future?

I like to say that if before we had the carrancas with us, now we will be our own carranca.

Vitória Cribb, 22, artist and industrial designer. Brazil/Haiti.

How would you describe your work?

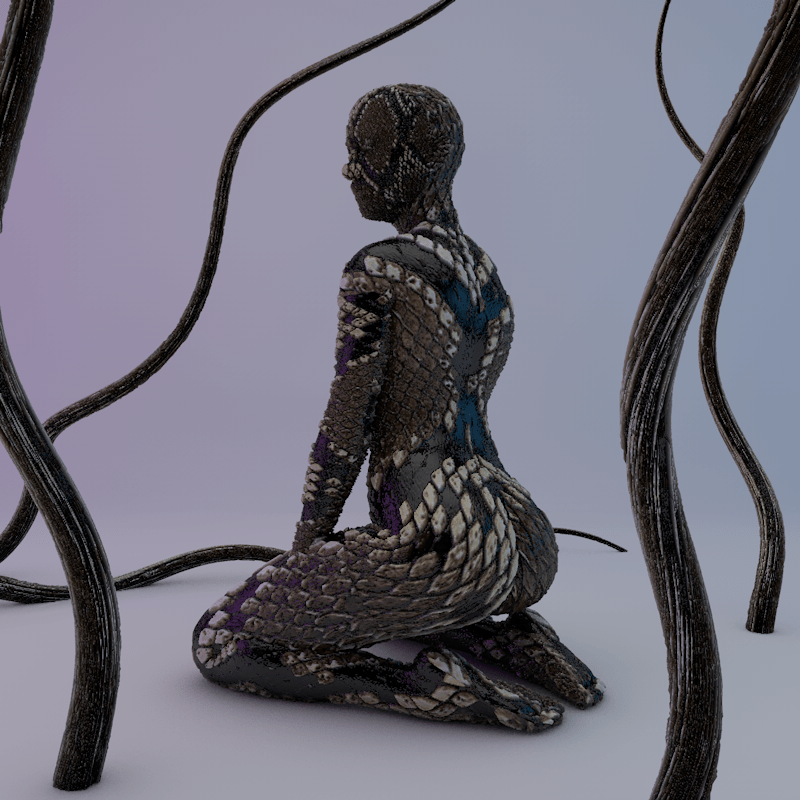

My work as an artist touches the imaginative, sensory, and interactive universe. My main media is digital, more specifically 3D modeling, and scenography where I create dystopian and parallel universes. I am constantly observing what is happening in the real world, in everyday situations where black people are treated as insensitive and invisible beings.

How would you describe your creative process?

My creative process is always part of some personal anguish, insecurities, questioning, and dissatisfaction with this apartheid bubble in my head. I always try to discuss this with black women and men around me, to understand how this affects them and start focusing on common points. For example, when I ask myself about the vision projected on me about being a strong woman, I begin to explore how to break this stereotype.

What are your main childhood memories and how do you believe they affect your work?

I remember how the family environment and the neighborhood did me good. I remember the Haitian songs that my father used to play and the dances with my mother and sister. It was an environment where I felt protected and happy, where I expressed myself expansively.

But there is the other side of the story: school, where I felt repressed from childhood to adolescence. A private school, where white students reproduced the racism they saw at home. European philosophy swallowed me up and I saw myself as abnormal. This, of course, affected my whole relationship to freedom. It was cruel and I wonder about a lot to this day.

You are far from the cosmopolitan axis of contemporary art. How does that manifest in your work?

I explore my pains, and the daily pains of black people. For example, the violent police treatment of black men, abusive and racist relationships that affect black women, toxic friendships, and university, that does not consider non-white world views as valid.

How does the digital world influence your work?

Knowing that I can create universes and invent narratives in another world fascinates me. What I love most is knowing that these stories and scenarios can be incorporated into the real world through new technologies such as virtual and augmented reality .

There are very strong spiritual and mythical aspects to your work. Where do you think this manifestation comes from?

Although I was a computer addicted child and teenager, I grew up in a family that has a very strong connection to nature. My father is an Agronomist and my mother a Zoologist, so the connection with land and animals has always been present in my family.

How does your understanding of art as a political tool influence your art?

First of all we need to talk about black women and girls in technology. Society still does not accept us and we are always discredited. We need to think about how technology and new media reflects the experience of being black. New media will have more influence on culture in the future so this is urgent.

How do you see the future?

Like a pot boiling over. The digital age has allowed people who do not have access to major centers of culture and art to expose themselves to new imagery research. With new media platforms and distributors, I believe that a cultural and economic revolution will happen within the fields of art and media. I hope to see it.