This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Voice of a Generation Issue, no. 356, Summer 2019. Pre-order your copy here.

When he was 11 years old, Félix Maritaud happened upon a book on his grandmother’s shelf. At the height of the pandemic, Cyril Collard’s Les Nuits Fauvres was considered the French masterpiece on AIDS and the modern man. Collard died March 5th 1993 at the age of 36, 72 hours before the film version of the text he wrote and directed won four Césars, the French equivalent of the Oscars. Maritaud was born the previous December. 11 years later, he read and devoured every word of it.

Collard’s inscription at the start of the book is as good an introduction as any to it: “What I write about is dirty: the street, mud, sex, illness. French cinema is a petite bourgeois which is scoured of all that is dirty, or at least, of what it believes is dirty.” If only Collard had lived to see Félix Maritaud as the nameless hooker in 2019’s first visceral counterculture classic, Sauvage.

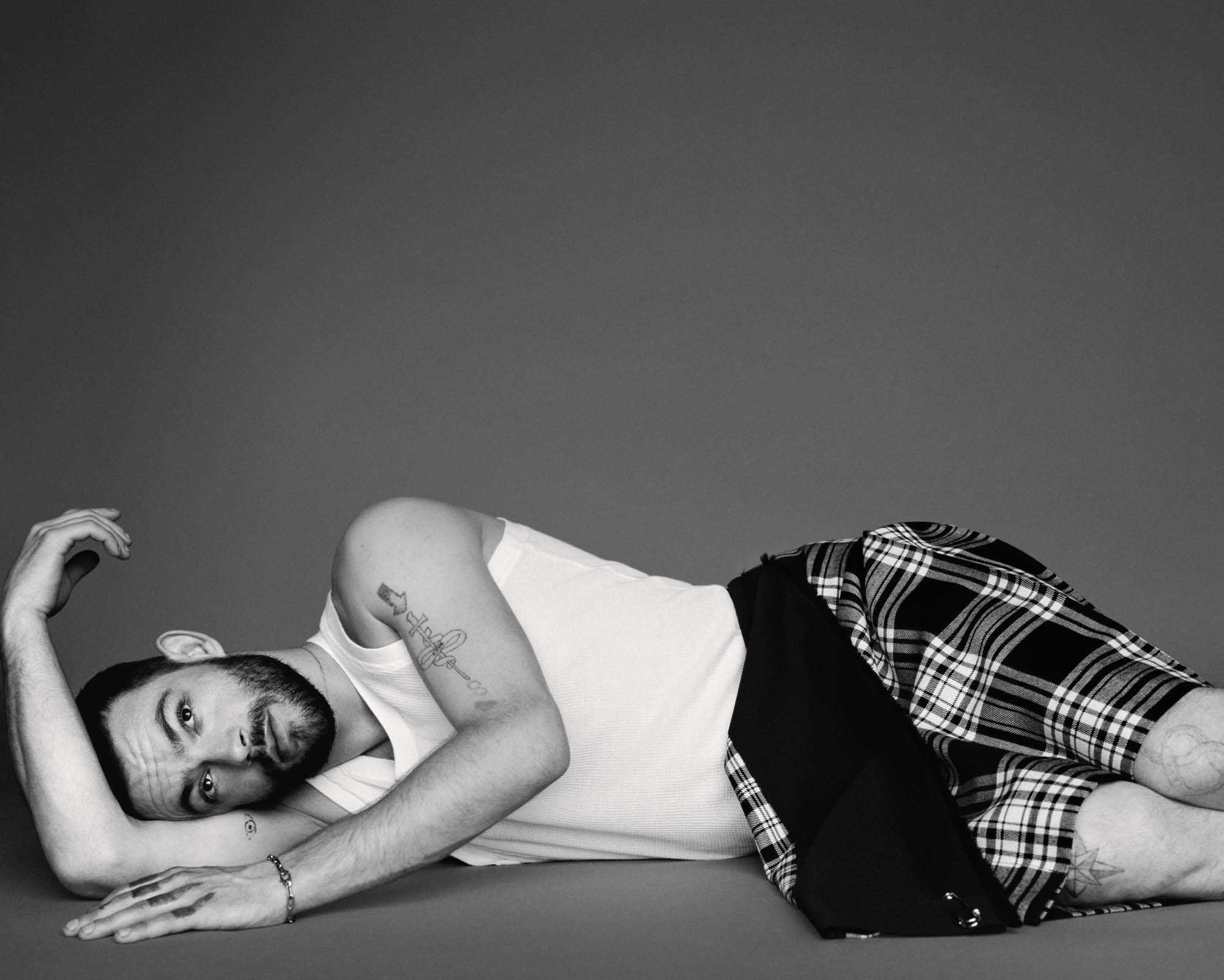

“I was very young to read it,” Félix says now, sitting on the patio of a Covent Garden private member’s club, chewing diligently on a succession of Marlboro Lights. “But even then, I could feel all of it, the desire.” Félix is wearing a fetching combination of distressed lilac leather trousers, black t-shirt and crystal pendant. He looks like one of those men Demna Gvasalia has directly in mind when designing for Balenciaga. His impeccable English is mostly learned from watching American TV and bad boyfriends.

He exudes a pleasingly salutary and mystical air when it comes to talking about his first starring role, but his confidence in the performance shouldn’t be mistaken as arrogance. He’s an indisputably beautiful man, on screen and off. “So yes, I was really young to read it,” he repeats, “but this is how I created who I am. By just accepting.” Les Nuits Fauvres was his first active interface with gay culture, a text with which he seems to have made a pact to honour later in his working life.

Maritaud’s performance in Sauvage is the heartbeat at the centre of the picture. It is his second major feature film, after a supporting role in Robin Campillo’s perfect evocation of the birth of the Parisian wing of the international force for AIDS activism, ACT-UP! In 120 BPM, he was street cast while training to be an artist. Now he is the strangest calibration of global film star, one whose work reflects his own radical philosophy. Félix is a find, a deeply physical actor for whom emotional and bodily boundaries appear to be all but invisible.

Sauvage traces his character across several unflinching professional appointments, in and out of doctors, to the disco, peddling his trade street-side, around a circuitous and unrequited love and into a fleeting moment of hopefulness with a suicidal man he meets on a bleak footbridge who believes he can save him. The sex is often hard, uncompromising and abusive. Wandering through it, Maritaud gives his hustler the freedom of ambivalence, even smudges of romance in his work.

“In Sauvage we are in the character always,” he says. “We are within him.” He talks about the character as if it is almost a fantastical version of what he can do with his body. “The camera in Sauvage is like a guardian angel for the character. Looking at him, caressing the body. It’s not a movie that speaks about something. It’s a movie that speaks from someone.”

During the filming Félix would frequently lose himself in the rhythms of the person he had become. Perhaps because he is untrained as an actor, the verité aspect of the work can feel like documentary. He describes his character as “kind of an angel, because he doesn’t belong to anything material. He has no materialistic things to bring into the world. He is only living through his feelings, through his tenderness and love. In mythology angels are not human beings. They are just feelings, emotions.”

At one point, his character is told by the rent boy he most desires that “We were made to be loved. This is the best we can do. Find an old guy. A nice one.” Of several heart-stopping moments in the film, Félix’s passive reaction to the observation cuts deepest and stings hardest. He wears the wildness of its title in every frame. “I wasn’t in control of what he was doing,” he says. “I think I just made my body available for him to live in.” The character research was minimal, by design. “We didn’t talk about his psychology, only about what his sensations are. So, I was just the body that was here to transmit the emotion of the character. I wasn’t in control of it because I don’t want to control somebody.”

Félix was shown a script of Sauvage in 2016. The director Camille Vidal-Naquet had written his debut feature film without ever intending it to be made. Filming happened over several weeks in Strasbourg in April 2018, taking care to anonymise the city. “Camille wanted the whole situation to show that in every European big city this happens,” Félix explains, “to let people into kind of a dream, to get out of the social issues beyond prostitution.” It is a rich, present work in which we feel every inch of the actor’s body as it offers itself as passing trade. “It’s a movie about the character, about humanity, tenderness and freedom.” In the making, he could touch something transcendent happening between subject and self.

The rhythm of the film has a stop-start quality that plays upon and subverts audience intrigue in the life of a hustler. “With sex work,” Félix says, “you have the feeling of desire and unease at the same time.” But the story is not about a profession.It has nothing to offer as a moral valedictory on the subject, as if foreshadowed by Cyril Collard’s ambiguity to the correlation between sex and death in Les Nuits Fauvre.

Félix’s amazing transubstantiation in Sauvage is to turn his character into a blush, a penetration, a promise and a deflation. “I don’t know who he is,” he says. “I don’t know his story. I don’t care. I just think he’s a vibration of life. He’s not information. I think it’s beautiful. It was quite special connecting to something that doesn’t exist at all. It was really true.”

Talking to Félix about acting, he makes it sound more like alchemy than science or skill. Sometimes he finds it funny even referring to himself as an actor. “Yeah, but in a way, it surprises me because I’m good at it.” He laughs. As his two accomplished debut performances reverberate with global audiences, he has no time for modesty. “I can understand why I’m here now. Because of the way I am and the way that I connect to things. I’m going to try and do better and better. But after being in something like this?” He lets the thought hang.

After first interacting with the force of intellectual and physical gay culture at such a young age, inevitably the reality turned out to be something of a disappointment as he made footsteps into millennial gay life. As a teenager he was a bona fide punk. “And there are gay elements in that culture.” But it wasn’t until he met a first boyfriend at 19 that he started going to gay clubs in Nice. “It was horrible,” he says flatly.

Félix doesn’t have a boyfriend. “Oh no. It’s quite difficult to fall in love with a man. I mean, I love a lot of people. But I don’t want a relationship like heterosexual people, a reductive, capitalistic relationship. Maybe as I get older, I’m going to need to share my life with one person. Not now.”

Some interesting twists have emerged since Sauvage’s release in the personal life of Felix Maritaud. He says the radical French Working Class writer Eduard Louis has been flirting with him on Instagram. “‘I like him,” he says, “because he’s one of the white homosexual guys who is the most interesting politically. We have a lot of views in common. We are sharing messages. But we’ve never met.”

He draws a connection in both of their work back to the godfather of French queer radicals, Jean Genet. “I like [Louis]’s point of view on racism issues in France. It’s really important that white people step in. Jean Genet once told that when black people are beaten and you don’t feel beaten, when a worker or a woman is taken down and you don’t feel taken down then your whole life you have been a fag for nothing. This is just the way I am. I think we have the opportunity by knowing what discrimination is because of our sexuality but we have the privilege of having a voice by being white people and men. We really have the responsibility of working with that.”

He intends to act on it, in all available ways. “These homosexual capitalist guys who stay on their own, they only do gay stuff, living a gay life,” he says. “These guys, I respect them the same way I respect homophobic or racist people, not at all.”

The reason the central character in Sauvage is not a selfish person is because the actor channelling him lost his sense of self. “I’m not into myself,” Félix says, with conviction. “I don’t care about myself. There are so many things to do in the world. France suffers from a big institutional racism problem. If you’re not able to watch that as a white guy, I think you are a jerk. Maybe you’re more a jerk than racist people, because you are a hypocrite. It’s horrible. How can those people stay like this?”

The best compliment he’s received so far on Sauvage is from queer artist and auteur Bruce LaBruce, who perhaps before the film had the final word in set texts on male prostitution with Hustler White. “He said it’s the best hustler film that has been done,” Félix says proudly. “That blessing means everything.”

Credits

Text Paul Flynn

Photography Alasdair McLellan

Styling Alice Goddard

Hair Ryan Mitchell at Streeters using KEVIN MURPHY. Make-up Lynsey Alexander at Streeters using Lancôme cosmetics. Nail technician Pebbles Aikens at The Wall Group. Photography assistance Lex Kembery, Simon Mackinlay and Peter Smith. Styling assistance Anastasia Xirouchakis, Georgia Pellegrino and Milena Ianniciello. Make-up assistance Phoebe Brown. Production Ragi Dholakia. Production manager Claire Hush. Production co-ordinator May Powell.