Michèle’s story originally appeared in i-D’s The Faith In Chaos Issue, no. 360, Summer 2020. Order your copy here.

“Here you are!” exclaims a warm Gallic voice down the line, its timbre as smoky as a cup of Lapsang Souchong. It belongs to Michèle Lamy. She’s at the Paris home she shares with her husband Rick Owens – five chicly spartan storeys that were, in another life, the French Socialist Party’s HQ, a stone’s throw from the left bank of the Seine. For someone who’s been living under one of Europe’s more restrictive lockdowns, she’s in bright spirits. “I’ve been in the house with Rick for two months, which never happens. Also, we have the studios here, so it’s possible to have ideas and create things,” she says. “And I’ve been able to plant my garden, so it’s been a good time for me.”

As far as confinement situations go, it’s certainly an enviable one – something she’s acutely aware of. “I’ve had a great time, but if I was living with five kids in a small apartment in Paris, and could only go out for an hour a day, I would see things in a very different way.”

For Michèle, the past months have been punctuated by many such moments of empathic reflection, and thoughts on the state of our world and the roles we need to play in it going forward. In an attempt “to find answers to difficult questions about what we’re here for,” she’s been speaking with friends and collaborators on Instagram livestreams, with each conversation centring on the question: “What Are We Fighting For?”

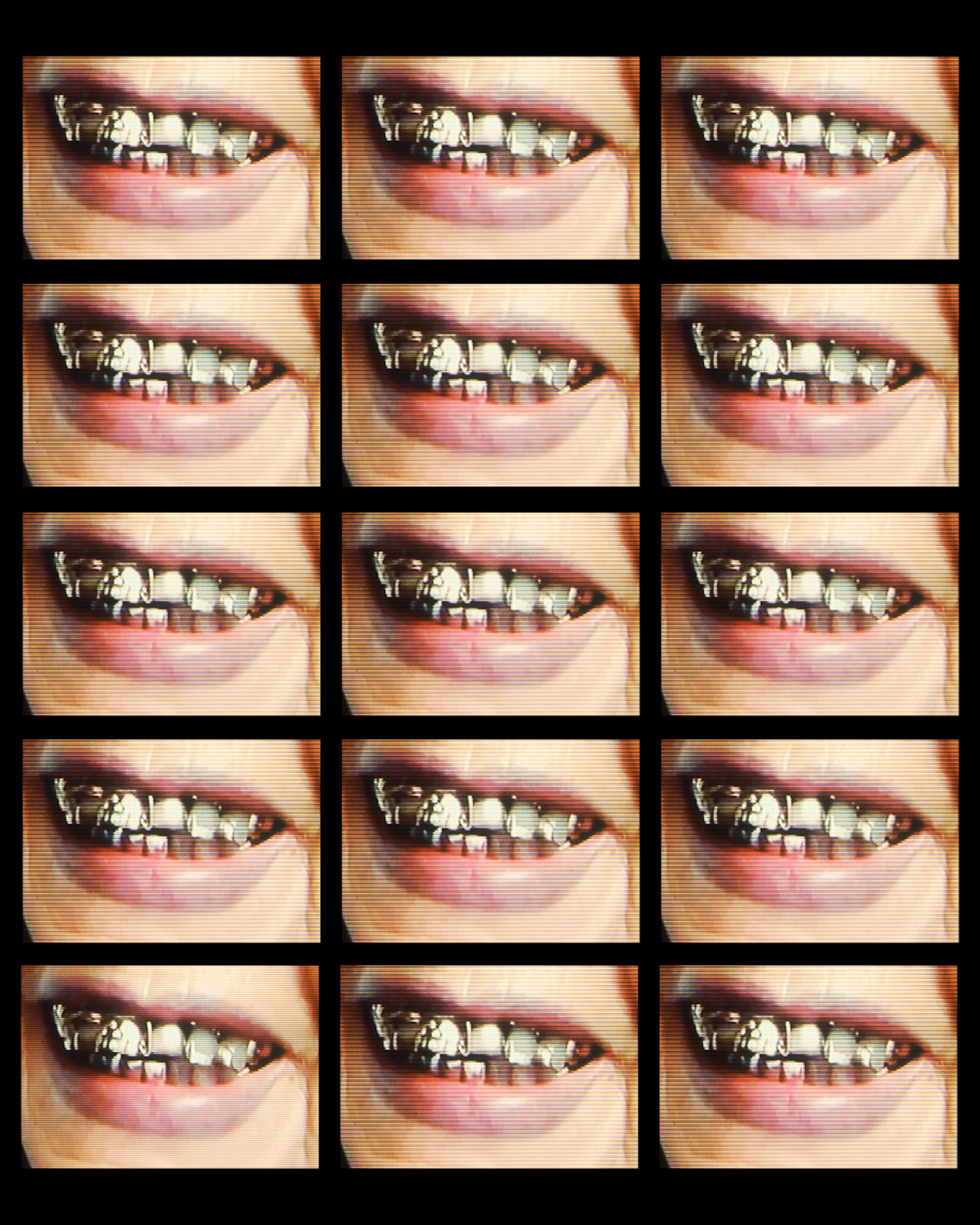

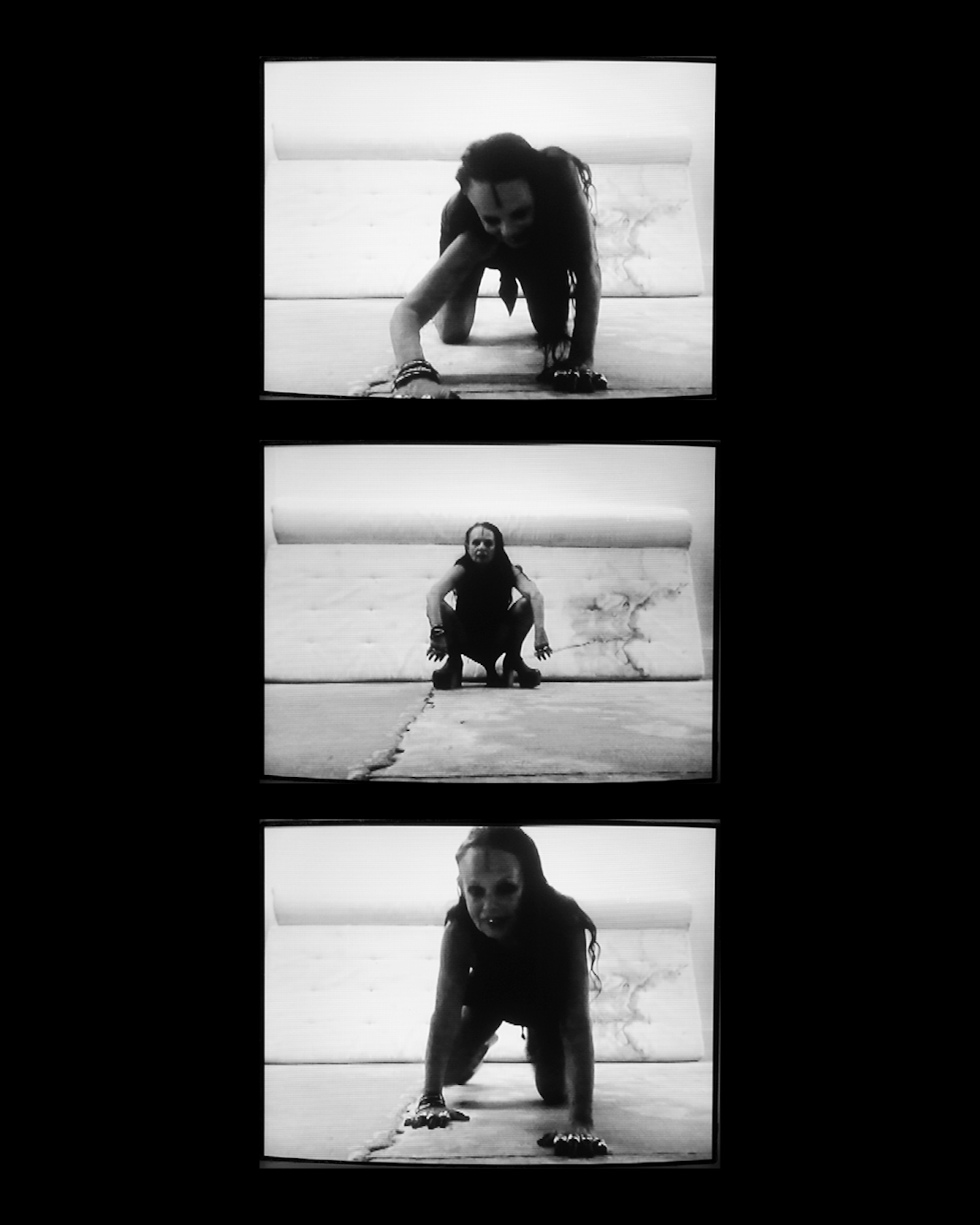

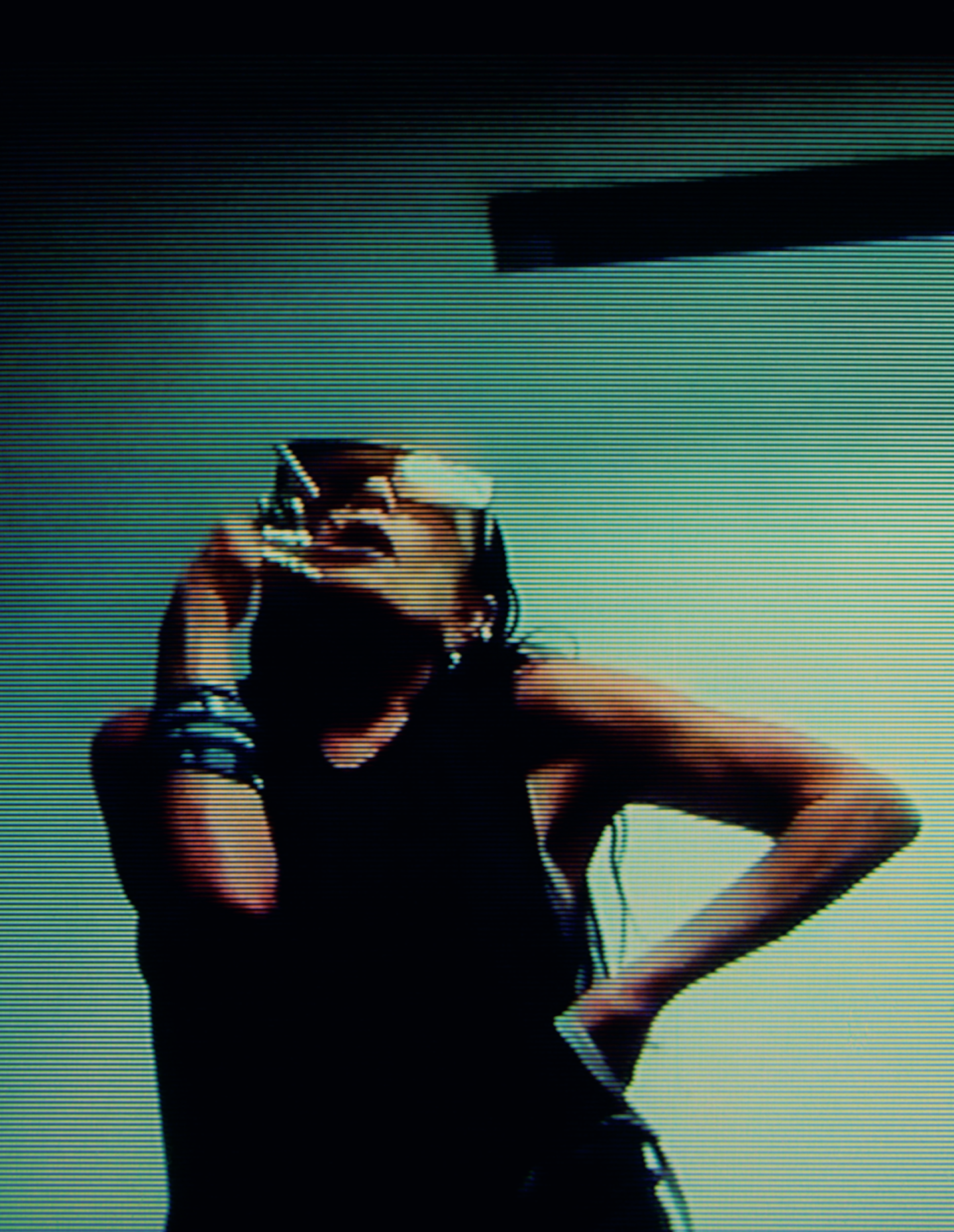

There’s a pun at play here. Yes, the question invites pontification on the paths we might take to overcome the hand-wringing existential angst that currently looms over us. But, as those who know Michèle know, the fight it refers to is also pretty literal. Though much attention is paid to her henna-hued hair, dye-stained fingers and gold-capped teeth, just as essential – if not more so – to the constitution of her character is her zeal for boxing. She first tried her (de-ringed) hand at “the noble art” just over 35 years ago, at the Wild Card Boxing gym off Hollywood’s Santa Monica Boulevard. What’s fuelled her passion since isn’t the rabid bloodlust often associated with the sport, but rather its central doctrine of focus and discipline. “There are rules. It’s a bit like chess,” she says. “It’s about learning how to look people in the eyes, and guess where they’re going to move.”

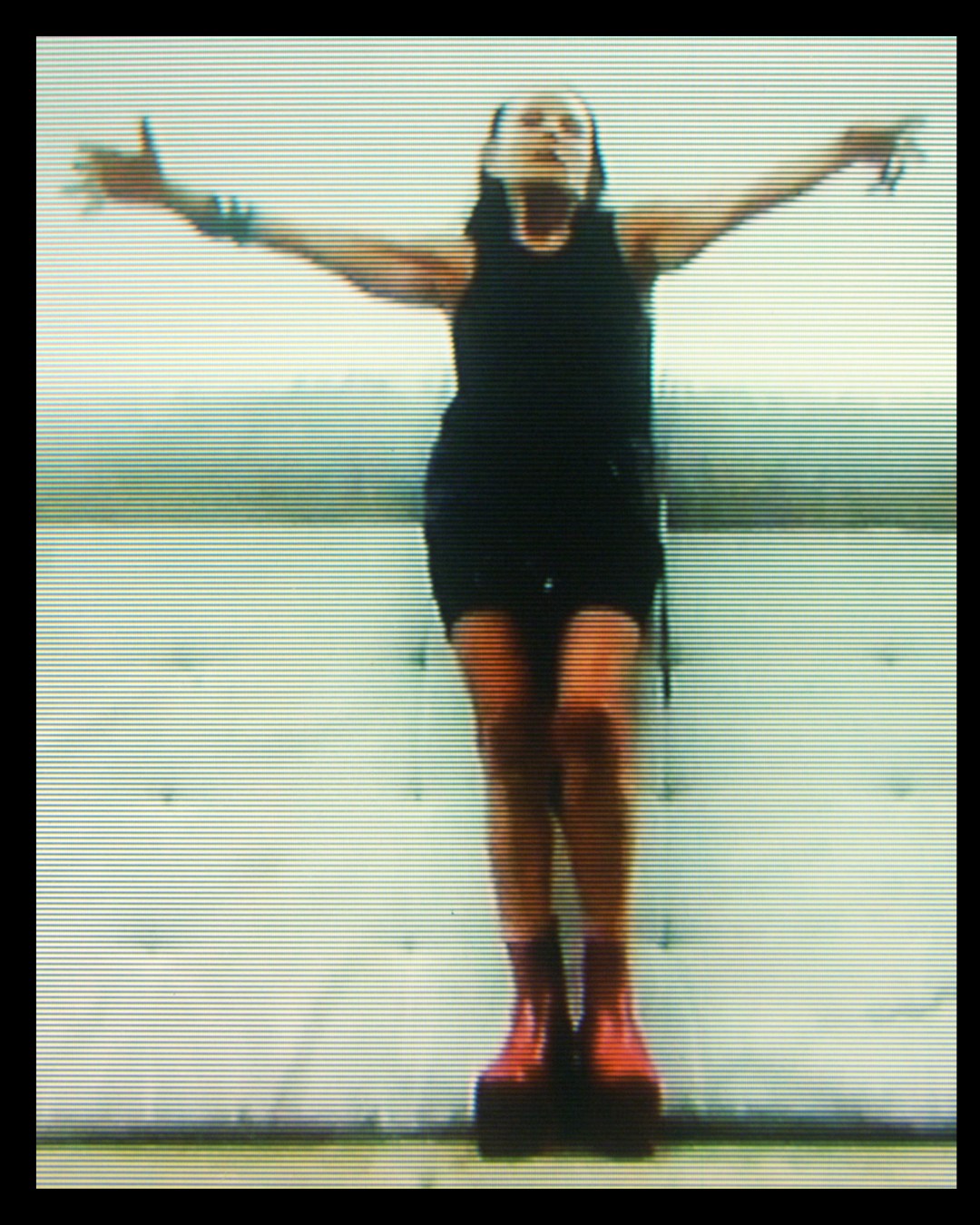

At its best, it’s a precise dance, a nimble and gritty ballet. “It’s very close to that. There’s music, there’s a stage, and then there’s the smell of the sweat, the wrapping, the ceremony,” she says, her delivery loading each word with transcendental significance. “It’s not a fight, it’s about standing for what you believe in – our culture, our humanity. For me, it’s all about performance.”

Performance is a love that runs deep in her veins. Deeper, even, than that for boxing. It’s been there since her choral days at boarding school in France. And it was there in her work as a defence attorney – a career as demanding of stage-ready charisma as any actor’s –which she later left for more adventurous pursuits. “I was doing striptease!” she says, hamming up the tone of a speakeasy compère. “I did it with a girlfriend of mine, Hélène Hazera, in little bars in the villages around Paris. That was fun.”

Clocking Michèle’s voice as a dead ringer for Marianne Oswald’s, Hélène, a music journalist, handed her an unreleased recording of “King Kong Blues”, a poem Langston Hughes scrawled on a napkin in a Saint-Germain club where the French vedette performed to music by Boris Vian. And when Michèle moved to the States for a 29-year period in the 70s – driven by a fatigue of French pop music and a love of Bob Dylan – those stanzas came with her, all the way to her Hollywood restaurant-cum-cabaret, Les Deux Cafés. “We started a scene there. I liked there to be a bit of performance at the end of the night at Les Deux, so I started performing “King Kong Blues” with Bobby Woods’ band,” she recounts. And she wasn’t the only one to take to the stage. From 1996 to 2003, Tinseltown’s it-clique – Heath Ledger, Madonna, David Lynch – flocked to an unexceptional car park just south of Hollywood Boulevard to drink Veuve Clicquot and witness impromptu turns by Joni Mitchell, Boy George, Grace Jones… Madonna, apparently, only ever danced on a table.

“Les Deux was my form of theatre!” she exclaims. And, as with any play, casting was key. “I was the only one to answer the phone,” she says, patiently sussing out prospective patrons before granting a table. “It was about placing certain people next to others, knowing there’ll be a scene,” she laughs.

Her approach may seem capricious to some, calculated to others. But it speaks volumes about what Michèle relishes in performance – its ability to bring like minds together to spontaneously create something new, to push ideas forward. “It’s always about encounters, being with people,” she says. Even when participating in formal performance contexts – her work with Caecilia Tripp and Cecilia Bengolea, for example – the result is always an organic product of and for that particular moment, rather than anything too planned out.

Similar can be said of LAVASCAR, the experimental band she formed back in 2017 with her daughter, Scarlett Rouge, and punk-musician-turned-artist Nico Vascellari – the ‘VA’ and ‘SCAR’, respectively, to Michèle’s ‘LA’. They’ve released two albums. The first, 2017’s A Dream Deferred, takes its name from another Langston Hughes poem – “Montage of Dreams Deferred” – lines and words from which are whispered, cackled and moaned over percussive EBM. Its 2018 follow up, Garden of Memory, is more cosmic in its scope, dreamier and more familiarly melodic, though no less brooding. It also marked a shift away from Langston Hughes as her poet of choice. “I went to Marrakech, and I discovered someone I now feel I’ve known forever, Etel Adnan. ‘Oh my god!’ I said. ‘There’s no more Langston Hughes, it’s just Etel Adnan.’”

Michèle’s work with LAVASCAR should not, however, be reduced to her reciting lines of poetry to a soundtrack. Rather, she sees each poem she refers to as a “dictionary”, a capsule of language to be redeployed on her own terms. “I like words, I like suggestions, I like voices. I don’t like stories where there’s a beginning and an end,” she says. “Some of the words in each poem are important, but I don’t need to say them all. I have stories within me to add.” Lately, she’s even considered putting pen to paper herself: “I’m going to dare to start writing something, perhaps… but, you know, there are so many great poets that say things so well… mais, voilà!”

It would be a welcome decision, given the wealth of tales she has to tell. In fact, when asked to define her life philosophy, Michèle routinely cites Scheherazade, the protagonist of One Thousand and One Nights, as a sort of literary soul sister – like her, she’s compelled to “continue telling a story, because otherwise, they’re going to cut my throat!”

Just what stories post-pandemic life holds is, of course, an uncertainty. It’s hard to know what it is we should be fighting for. Michèle’s not sure either, despite the clairvoyant energy she exudes (she’s often mistaken for a tarot reader by Parisian taxi drivers). One thing, though, is clear. “Finding answers will be a slow process, but I hope that nothing will be the same as it was afterwards,” she says. “It has to be another way.” And wherever that way leads, Michèle Lamy will be there – on another day, with another story to tell.

Credits

Photography Tyler Kohlhoff and Lana Jay Lackey