As the millennium roared to a resounding end, a young teen named Mike Brodie and his mother rode a Greyhound bus across the United States to begin a new life in Florida. “My mom is a Christian, and God told her to leave Arizona,” Mike says. “My dad was just getting out of prison, and she didn’t want to confront the realities of getting back with him.”

They arrived in Pensacola around Christmas and stayed with family until his mother was able to afford a place of their own, right off Burgess Road. The house was located just a couple of blocks from the a major railroad mainline back when the city played a significant role on the Gulf Coast corridor. Although Mike was not particularly interested in trains as a kid, as he grew into adolescence, things began to change.

Young, restless, and possessed with a sense of urgency to explore, Mike would take off on his BMX bike, hit the streets and hang out with friends. But the thrill of two wheels didn’t quite suffuse the sense of boredom that he felt. “The rest of my time was spent at home, lost, listening to melancholic music, playing Tony Hawk Pro Skater, trying to watch dial-up internet porn, and playing the same Red Hot Chilli Peppers album over and over,” says Mike.

One day in 2003, while washing dishes, Mike gazed out the window and saw a young couple sitting close together in the car of a freight train as it zoomed along the tracks. Although it was just a passing vision, something clicked. “It showed me that a train could take me away,” says Mike. “I can’t determine if it was punk or simply curiosity and rebellion that led me to the rails. Punk made me feel less guilty about being rebellious, committing petty crimes, and breaking laws. But punk didn’t teach me DIY, and it surely didn’t teach me to think for myself. I feel I was born with a natural sense of wonder and a curiosity to explore the world and fix things.”

At the time, Mike was staying with his girlfriend at a “punk house” home to radical feminists. “The house would get visitors from time to time, usually in the form of a band who was on tour or a crusty kid just passing through,” he says. “This is where I met my first train rider, Scott Youth. He was sleeping on the front porch and said he was from Chattanooga, Tennessee. He had a pack, a dog, and very unkempt facial hair. I thought he was in his 40s, but apparently, he was 19 years old.”

As the teens sat on the porch talking, an intermodal train passed by the house; Scott told Mike it was a “hot shot” bound for New Orleans. Mike watched the serpentine line of colourful shipping containers and Tropicana juice cars sail down the track. “It was beautiful,” he remembers. “I was hooked. I knew I had to ride one.”

Two weeks later, Mike was gone. On the 4th of June, he hopped his first freight under the I-110 overpass just as the trains slowed down to take the curve. “I had no idea what I was doing, but I was doing it,” catching a “53′ suicide” (bottomless) car on the fly, risking life and limb for the ride. He rode eastbound along Scenic Highway and over the Escambia Bay Bridge before stopping near the county landfill where a flock of seagulls regularly scavenged for trash.

As fate would have it, that same year, Mike happened upon a Polaroid camera stuffed behind a car seat. He started bringing the camera on adventures and, over time, mastered the form, earning the name “The Polaroid Kidd”. But getting the shot proved a challenge all its own. “I was far more shy and insecure then, so my approach was all off,” he says.

“Also, the country was still in post-9/11 paranoia, so anyone with a camera was suspicious, especially a dirty kid approaching normal working-class people. Many people were involved in radical activism and didn’t want their names or faces online or had their concerns around the idea of ‘selling out.’ Luckily, I am a ‘light shooter’, as they say, and only photograph certain people. I feel there really must be that visceral emotion; otherwise, the photos just don’t have ‘it.’”

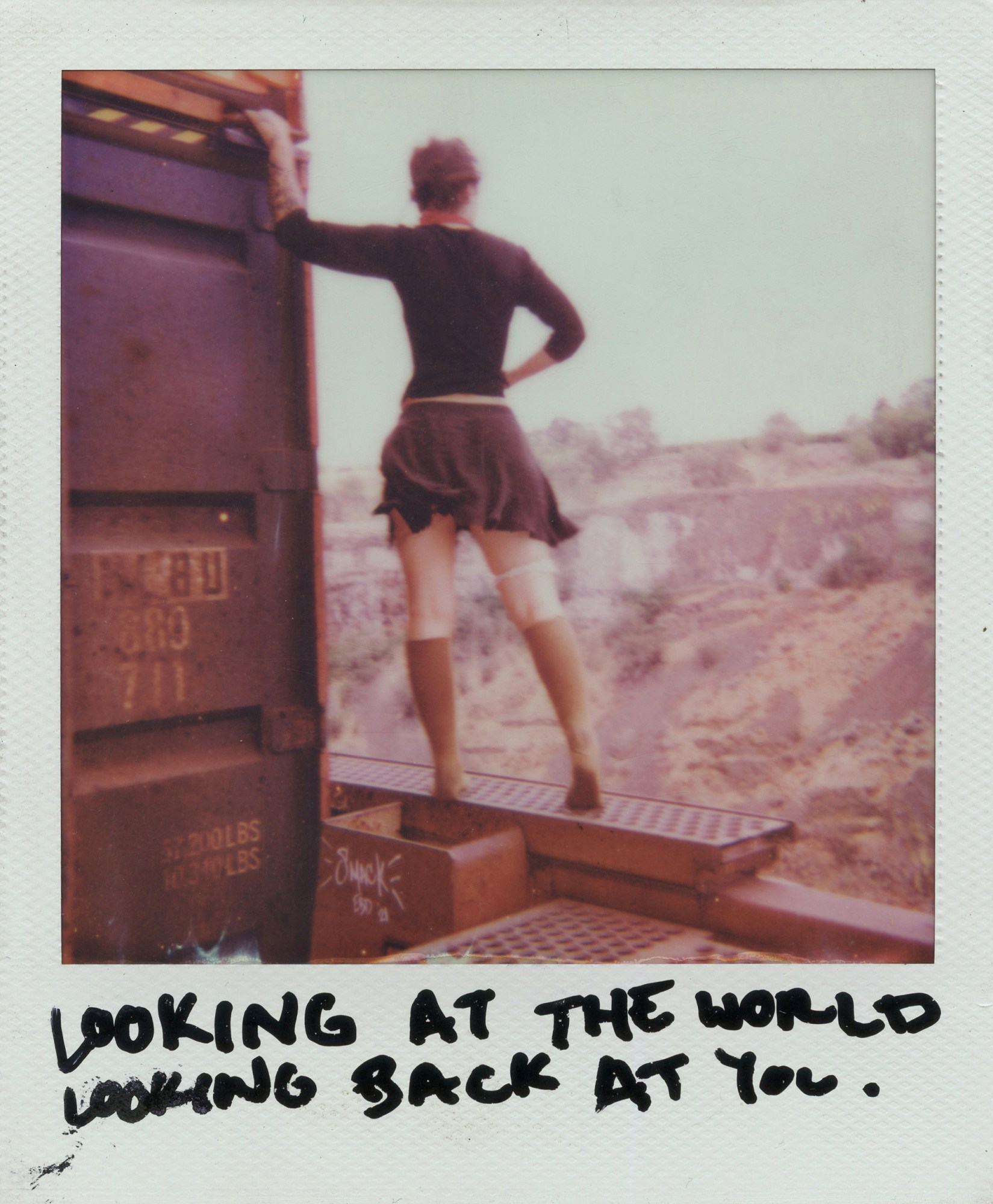

Mike began posting photos online in 2004, back when the internet was still an open frontier and not yet fully integrated into the mainstream. As he honed his craft, he switched over to a 35mm camera, amassing a body of work that would later become a landmark 2013 book, A Period of Juvenile of Prosperity (Twin Palms). Now, on the 20th anniversary of his very first trip, Mike returns to his archive and unearths the work that earned him his fabled moniker, The Polaroid Kidd (Stanley/Barker), which launches on Friday, the 22nd of September at Dashwood Books in New York.

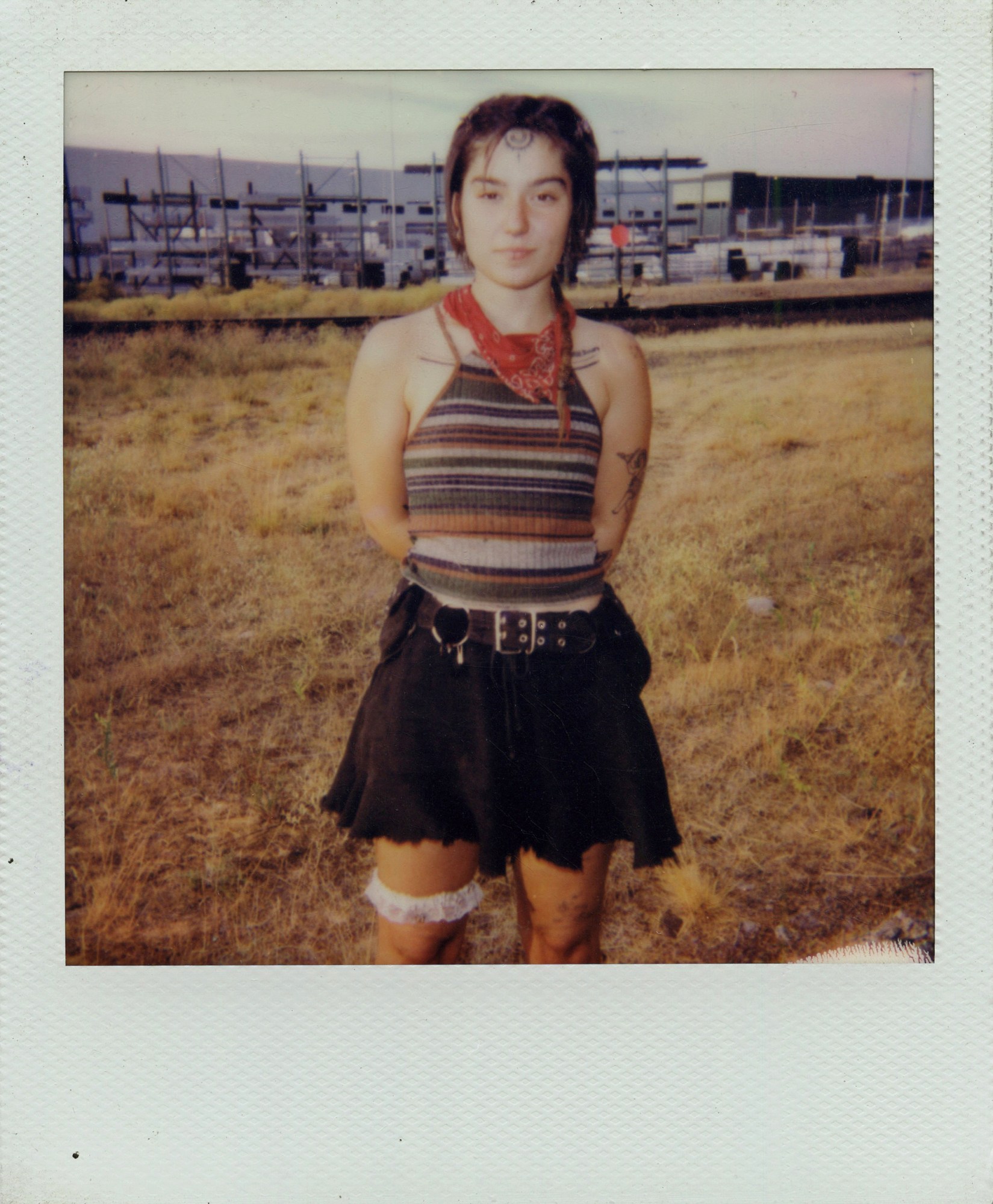

The Polaroid Kidd is a perfect artefact of an earlier time: a box set of 50 facsimile Polaroids filled with a poetic romanticism, melancholy, faded nostalgia and a sense of longing that evoke a curious blend of old American values meets punk radicalism. Here in Mike’s photos, we disappear into a world that exists in the fleeting beauty of our deepest longings that go largely unfulfilled.

“Most riders initially attracted to this life are typically 16-25-year-old punks that have poor relationships with their father, or no father at all,” Mike says. “The lure of rails might offer hope, romance, redemption; some find it, but most don’t. And ironically, most riders who live past their 30s and 40s denounce the lifestyle altogether, settle down, have children, cover up or get tattoos removed. Most won’t admit, but it’s what everyone was chasing all along: true love, a relationship, family, and permanence.”

For Mike, train riding has always been a solo act. “It is a lifelong obsession that has been as rewarding as it has been heartbreaking,” he says. “Although I often enjoy the company of others, any semblance of real brotherhood only existed briefly within a drug-addicted or alcoholic haze. The highs of the lifestyle are really high, and the lows are really low. Train riding can be so much fun, but once the dopamine wears off, you’re left with the realities of your life choices: silly road names, tattoos you can’t remove, scars that won’t heal, addictions that are hard to recover from, and the loss of friends that were taken from us too soon.”

Mike reveals he is now working on a second box, tentatively titled Ethereal Wraith, which brings together the work of Mia Justice Smith, aka “Slack”, a former girlfriend who died last year. The project, which features all of Mia’s work since high school, including photographs, videos, journals, and relevant social media, will coincide with an exhibit at the Alabama Contemporary Art Center in 2025.

Revisiting this chapter of his life, Mike feels a sense of duality that comes with blurring the lines between life and art. “Many of the images have been viewed so many times that they’ve become impersonal art objects, which I feel completely removed from,” he says. “I remember before I picked up the Nikon, having a vision of a couple dirty train riders, ‘punks’ or ‘hobos’ riding in a coal car across Montana, a place I had never been. Then, one day, the image became a reality and manifested itself in my own life. I don’t know how. Looking back, it’s as if it never really happened. I was never a photographer holding a camera but a vessel to tell a story. It’s like it all existed within a dream, and this is just God’s plan for my life.”

‘The Polaroid Kidd’ is published by (Stanley/Barker) and launches 22 September at Dashwood Books, New York

Credits

All images The Polaroid Kidd © Mike Brodie and Ethereal Wraith © Mia Justice Smith