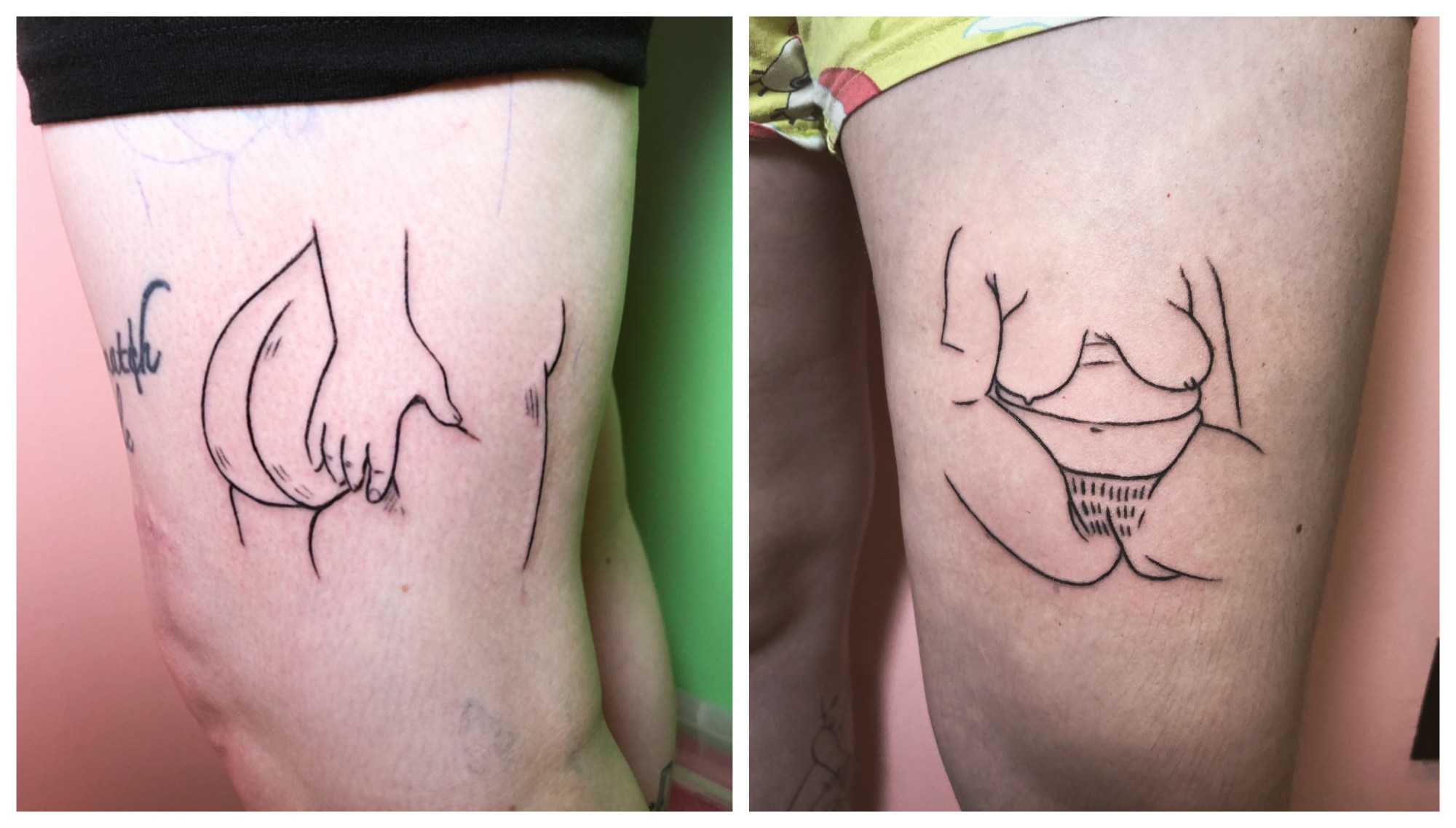

The hand-poked tattoos of the Seattle-based artist MKNZ are deeply personal: “My style developed as a natural extension of how I draw and journal,” she says. Her doodle-like designs include sleepy swans on rainbow clouds, tear-filled eyeballs, and hearts and triangles with various inscriptions (“queen,” “trans” and “they,” to name a few). “My content is intentionally loud, lewd, provocative, and extremely dykey,” she explains. “It’s a lot like me, I guess.” For MKNZ, who describes herself as a “fat, femme, queer woman,” her content resembles her in another way too — fleshy figures grab, squeeze, and proudly display their fat rolls. “Positive representation of bodies that look like my own is absolutely critical,” the artist says. “It’s about survival and it’s about freedom from the boring and suffocating standards of beauty upheld by the capitalist patriarchy to keep power in the hands of white cis men.” In the following interview with i-D, MKNZ talks dirty tattoos, intersectional values, queer tattooing, and fat acceptance.

How did you first get into tattooing?

I started tattooing in my early 20s in a house on Capitol Hill. I had a lot of enthusiastic punk friends that were more than willing to let me learn how to tattoo on their bodies. For the first few years, I just maintained a pay-what-you-will, sliding scale kind of practice. This worked for me at the time, because I also had a day job that allowed me to pay my rent, and it took me a long time to find the confidence to believe or assert that my work was of value. I was also afraid of assigning value to tattooing, because I enjoyed doing it so much, and monetizing things seems to have a way of ruining them sometimes. Luckily, I am still totally in love with tattooing, all these years later.

How did you develop your style?

The kinds of tattoos that I like are very reflective of my early history with tattooing my friends, lovers, roommates, and community in unorthodox spaces. I love a “bad” tattoo, an old tattoo, a faded, blurry, or incomplete tattoo. I love tattoos that give an indication of the conditions under which the tattoo was applied. Keeping my material as filthy as possible also helps me weed out the squares. I’m never really contacted by bros for tattoo work. Cis men rarely contact me in general, but the few that do are particularly sweet and respectful. I’d prefer to keep it that way.

When did you start at Valentine’s Tattoo and what is it like working there?

I’ve been at Valentine’s for over three years now. Shannon [Perry] opened the shop by herself a year before I joined her. When I heard the announcement that she [wanted to] bring on another artist, I nervously reached out to her. She was already operating on the fringe of Seattle’s tattoo scene and she took another risk when she brought me on — an un-apprenticed hand-poker with no professional shop experience. I was so grateful and over the moon then and I still feel that way all the time. There are seven of us now, and I love and respect everyone I work with. It’s a dream.

Can you talk a bit about the values of the shop and people working there?

There is a lot of work that goes into upholding values of inclusivity in a creative space and we recognize the responsibility that comes along with serving the community that comes to Valentine’s to get tattooed. We take this work very seriously and are trying to create a safer environment and uphold higher standards of accountability all the time. We have clients who comment regularly on having never felt safe or respected in a tattoo shop and feeling at ease in Valentine’s. Maintaining safer spaces means having a zero-tolerance policy for racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, fatphobic, ableist, and otherwise hateful speech or behavior in our shop. And standing by these intersectional values means that we have to continually assess our own practices and behavior individually; we all come from different backgrounds and have different levels of privilege to examine. Because Valentine’s is managed by white people, that work will never be done for us.

How is queer tattooing changing tattoo culture as a whole? What still needs to change?

I think, on a good day, queer tattooing challenges the narrative that tattoos have an obligation to be any one particular thing. On a good day, queer tattooing builds communities and strengthens bonds between queer people; it puts power and agency back into the hands of the oppressed. On bad days, queer tattooing still prioritizes whiteness and appropriates imagery sacred to other cultures. On a bad day, it is racist, transphobic, fatphobic, ableist, or classist. White queer tattooers have an obligation, in my opinion, to uphold intersectional values, to educate themselves on areas of oppression that they do not experience themselves, and work to dismantle colonialist values in their own practice.

Also, we need to understand that, though our safety grows in our mutual identification as “queer tattooers,” our work, our lifestyles, and our communities are not homogeneous. Queer tattoo culture in Seattle looks different than queer tattoo culture in other cities, rural communities, or other countries entirely. I think we should treasure these differences and use our individual platforms and varying degrees of social capital to lift each other up and reject impulses to be competitive or exclusive.

Why is it important to you to represent fat bodies in your work?

This comes back to visibility for me… I didn’t start really looking at my own body with love or even neutrality until I started looking at other positive representations of fat people. And positive representation of fat bodies in mainstream media is not an easy thing to find. Fat bodies are almost exclusively viewed through a lens of violence. Fat bodies are regularly tormented, teased, violated, humiliated, or entirely disregarded in popular culture. So, for me, positive representation of bodies that look like my own is absolutely critical.

Can you explain how fat acceptance is different from body positivity?

Fat acceptance and body positivity are different because the term “body positivity” has been largely co-opted by non-fat, predominantly fitness-centric communities as a way to express general, self-congratulatory positivity for having a body that is already accepted by society. Though it is important to try to love and accept your body on a personal level, there is nothing radical about expressing positivity toward thin, white bodies. We have to be more specific, hence the term “fat acceptance.” Fat is not a bad word, it is a descriptor. It is important to me that this word is part of my identity. I knew I was fat before I knew I was queer, before I knew I was an artist, maybe before I knew I was a girl. So when we treat this word like it is anything other than a neutral adjective, we reinforce the idea that being fat is a shameful thing to be.

Why do you think it’s important for non-fat people to talk about this issue?

When fatphobic rhetoric goes unchallenged by non-fat people, it normalizes that language and perpetuates the dehumanization of fat people. I think there are many allies who understand this, but hesitate to speak up for fear of saying something the wrong way. I know it is scary to speak publicly about oppression that you do not personally experience, but it is better to have these difficult conversations, and maybe make mistakes sometimes, rather than sit idly by and let the oppressed do all the work.