Open any social media platform and you are likely to see calls from artists, venues, festivals, and conferences to “tune in to our livestream”. With live music being cancelled, many have turned to broadcasting a performance from inside their homes to replicate the real thing. Completing the picture of crisis are the widespread pleas for donations to support the people and companies in the nightlife economy. Combine the stream and donation and you get the fundraisers we’re seeing now, from Patreon’s “Weird Stream-a-thon” to the Berlin club scene’s United We Stream. But what comes next? Can livestreaming really help artists get on top of this?

We are just at the beginning of the coronavirus crisis. It won’t be a matter of weeks, but rather months. In the northern hemisphere there is hope that the warm summer weather may slow down the virus’ transmission rate, however there is currently insufficient data to provide certainty and new viruses tend to spread outside the normal seasons of their more established cousins. As we enter recession through a global economic plunge, we will feel the effects of this period for years to come.

“It’s the worst moment to be asking people for money, because everyone is struggling for money,” says David Weiszfeld, founder of Paris-based music analytics firm Soundcharts and manager of French electronic artist Petit Biscuit. Although he also adds that “there are going to be some cool initiatives [in this time] that are going to stick, such as private concerts for Patreon supporters”.

One of the problems with livestreams is that there are no clearly established business models around it for artists, with donations being the most straightforward way of monetisation. For this reason, David suggests current livestreams are more about the direct experience with fans and artists trying to express themselves and communicate at a time when everyone is worried. With everybody going live, it remains to be seen how many people will actually be able to derive meaningful incomes from streaming.

“Dumb” is what David Turner, author of weekly music streaming newsletter Penny Fractions, calls “the idea that an entire creative class of people in a global pandemic can easily shift to a [livestreaming] career” and argues that some of the success stories we will see should be seen as exceptions that prove the rule.

Sebastien Lintz, founder of digital agency NXTLI and label director of Revealed Recordings, founded by Dutch DJ Hardwell, worries about artists getting into livestreaming. “The problem with platforms like Twitch is that you’re competing with people who have been doing this for years, like gamers. They have set up all the microtransactions, the hardware, and they know how to interact with their audience.”

Don’t musicians know how to interact with their audience then? They’re in front of audiences all the time, after all. Sebastien explains that it’s not the same with a livestream. Most artists are used to broadcasting things out into the world: from social media posts and interviews, to the music itself. Experienced streamers however, will thank every single fan for every donation on-stream, no matter how large or small. “How many artists do you see replying to every nice comment they get on social media? People will have to change their mindsets.”

He argues that the real problem is that artists don’t have their house in order in terms of business models. “People were too focused on events and never built out their company, because that’s what you are as a musician. You need to create independence from a singular revenue stream. What if you lose your hearing or get injured?” It never took a pandemic to take away the live revenue stream.

As basic advice, he suggests artists focus on a clear call to action whenever they express themselves, so that existing fans or newcomers who come across their livestreams, social media posts, or music, know exactly what to do to support the artist. “Of course people will want to do something to support you if you’re adding something positive to their lives. But you’re going to have to be really clear about what you want them to do.”

A great example of this clarity was recently provided by Discwoman during a fundraising stream which attracted 5,000 digital ravers. When the first restrictions for events hit New York, the collective of femme and non-binary artists arranged an empty space, set up their hardware, and got 10 performers to play to a global audience through Twitch. Throughout each one-hour set, the artists’ Venmo or PayPal details would be visible on-screen at all times. Prior to the stream, Discwoman had already been experimenting with new sources of revenue around their podcast series DiscUs, which they set up on Patreon earlier this year and is already collecting around $400 per month.

One of few artists lucky enough to have a baseline income secured through a membership platform is Sam Aaron, who has signed up hundreds of supporters on his Patreon. The creator of Sonic Pi, a tool for people to ‘live code’ music, has lost 3 months worth of salary to date. “Unfortunately I [have currently] lost my main income stream which is from talks, performances, and workshops.” His plan is to compensate for lost income by making tutorial videos for live coding music. “Sonic Pi will remain free,” he adds, “that’s more important now than ever.”

Education also plays an important role in livestreams. American producer Jauz has been running regular Twitch broadcasts on which he’s been working on fans’ demos since September. “Demo roulette“, as he calls it, sees Jauz working on tracks that fans submit. He critiques it and shows how to make things sound better, providing fans with valuable insights into his production process.

There’s no shortage of concepts. While on the phone with Sebastian, he threw out so many ideas for artists to try out that it was impossible to note down most of them. “Teach people how to play your songs, so they can entertain their neighbours when everything gets locked down like in Italy. Who knows — maybe it goes viral.”

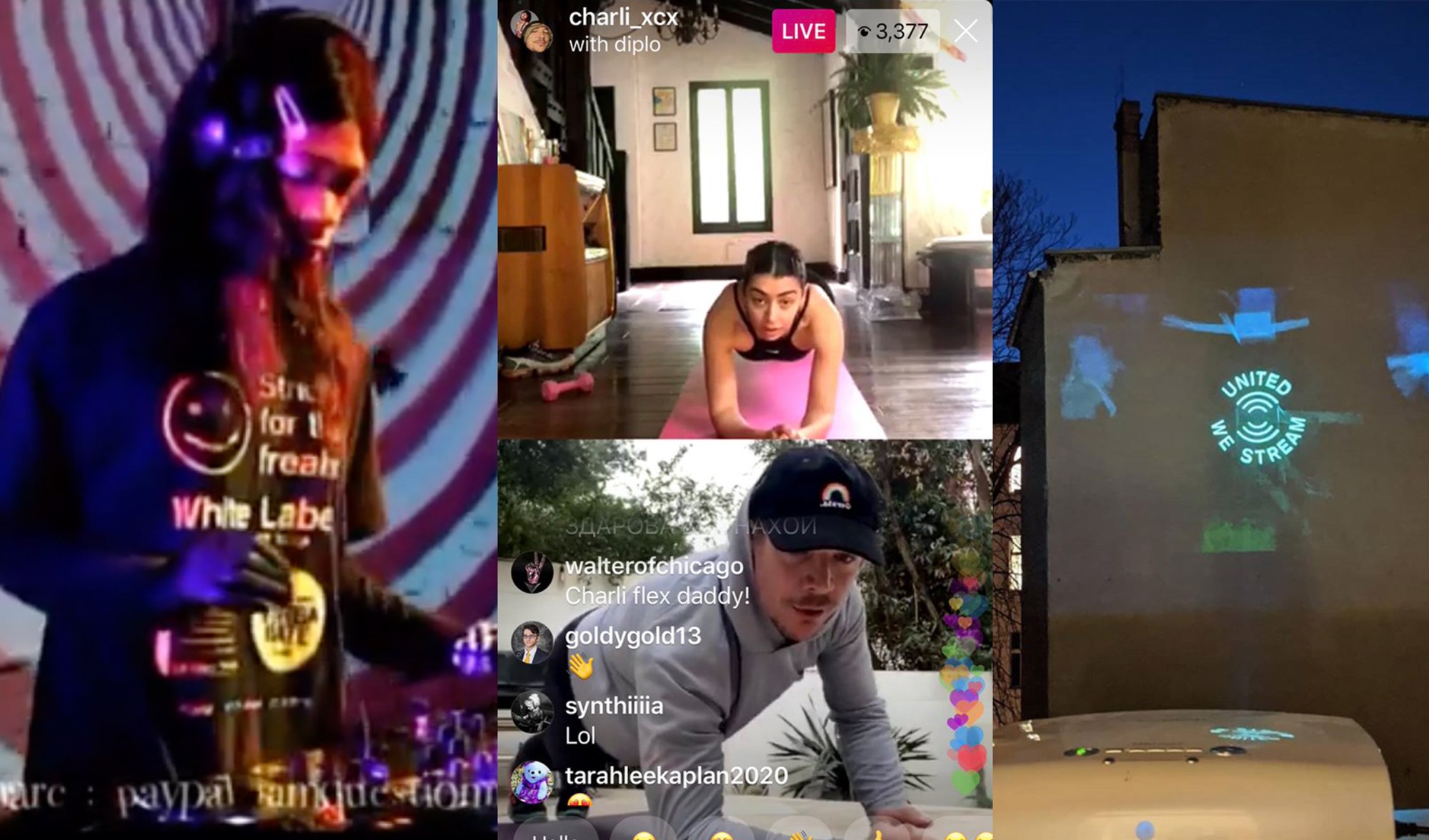

The most important thing here is that artists figure out what they want to be doing and what resonates with their fans. Whether that’s simply trying to cope, like Charli XCX’s coronavirus diaryturned Diplo quarantine work-out sessions, to playing video games while chatting with fans, like VR DJ Grimecraft.

So what should artists focus on right now? “Build brand equity,” says Sebastien, “build out your revenue streams, release more. Instead of once per month, perhaps do as much as once per week. Put time into ways of making your income more predictable.” He cites Hardwell as an example, who has his own label, his own publishing company and keeps a steady rhythm with releases, which means predictable income. “Then save your money and invest it somewhere.”

“Music brings people together,” says David from Soundcharts. “As soon as this virus goes away, people will want to be in the same place. We are going to have some of the best tours that we’ve ever seen.” For now, that means adapting to survive, but he remains hopeful and urges artists to “prepare for the day after”.