I let Myspace break my heart exactly once before I broke up with it forever: when, years ago now, they deleted every user’s comments, blogs and messages without warning. I had long migrated to Tumblr and Facebook, but found myself devastated all the same. I spent hours trawling the internet for answers, obsessively refreshing the wayback machine in a fruitless effort to find some cached version of my page that might hold my ex-boyfriend’s obsessive love notes or comments from band members that probably shouldn’t have been talking to me, a teenager, at all. After that I gave up, turning to my screenshots for comfort.

Despite lying dormant since then with basically no active users, Myspace managed to break even more hearts recently when they lost all content, including music, uploaded before 2016 as a result of a “server migration project”. That’s over 50 million songs from 14 million artists. It’s almost funny how the guardians of our archives can be so hapless, that it’s even possible to do this without realising how much it might mean to someone. In a statement, the company soothed any ensuing wounds by adding “we apologise for the inconvenience”.

And this – surely – has to be it for Myspace. The site as we knew it died when its co-founder and mascot, Myspace Tom, jumped ship. Once forcing his way into your life via your friend list like an awkward dad, Tom stopped being president of the company in 2009. Now, he’s living large, far removed from any of this. His Twitter bio wholesomely reads “Enjoying being retired / New Hobby: Photography” and he seems to be using his money to eternally gap year around the world while businessmen puppeteer the ghost of the site we once called home, rinsing it for every last penny.

Myspace’s stalwart refusal to either lean into what it was good at (personalised blogs, essentially) or protect our digital archives has rendered it entirely dead. Seemingly unable to keep up with any advances in social media platforms or to even make it possible to save the shreds of culture left, the team behind Myspace have turned it into an empty, clinical-looking, unnecessarily sideways shell of what was once there. Many of us have chosen, for the last ten years, to act as if Myspace doesn’t exist at all, our accounts only active for us to dip into a watered-down window of our past lives.

If we are to mourn Myspace now, albeit 10 years too late, we are to recognise what it was. In the mid-2000s it was home to countless emo and scene kids from all over the world, plastering their fringes across their faces and hunting out new bands to cry to. Due in part to its ability to play and post music, it became the home of a number of subcultures over the years: yes emo, yes scene, but also teen rappers, indie kids and nu-ravers. That was also in part due to the fact that you could customise every aspect of it – why migrate to Facebook when on Myspace I could show exactly who I was through fonts, backgrounds and colours?

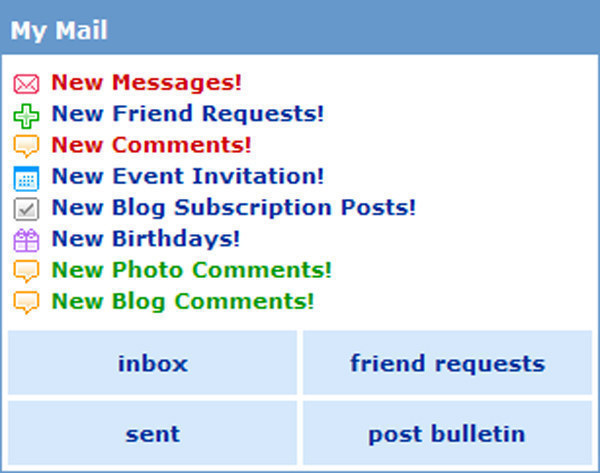

Myspace brought me people I am friends with to this day. Through comments, messages, PC4PCs and <3s, I connected with other emos in my city and built strong, lasting friendships, some of which even made it into my top 8. I learned basic CSS and HTML through tweaking my own page obsessively every day ( & hearts ; ). I showed the world exactly how much I loved Good Charlotte by forcing everyone to listen to whatever niche B side I had made my profile song. That personalisation was at the root of what kept us coming back to Myspace night after night, and we thought, for some reason, that it would always remain the same. Advertisers thought differently.

But for people who made music and didn’t just listen to it, this move means, sadly, more than an “inconvenience”: it means that a lot of fledgling (now likely retired) artists whose homemade demos only ever existed on the site have lost a small piece of their history. Myspace’s music culture, at the time, really meant something. It carried the same weight that Soundcloud does now, where new artists with little money, contacts or resources could record music within their means and share it for free. They could add potential “fans”, launching a model for PR that many artists attempt on Instagram and Twitter but that doesn’t seem to be as successful. On Myspace it was. Artists like Bring Me the Horizon, with the benefit of an even playing field with larger artists, made it big. That’s how subcultures came to be born and to thrive there. Back in 2008, Myspace attempted to relaunch around music, but with the fans no longer on the site, it proved to be a failure. Then, in 2011, the company was sold for $35 million to an advertising platform, rendering any shred of user-ownership the site ever had long gone.

For people with forgotten teen demos floating around on Myspace but not diligently saved to hard drives, this “mistake” is the final nail in the nostalgia coffin. This of course raises a lot of questions about just who we trust with our precious childhood memories – ultimately, it shouldn’t be companies with no interest other than $$$. Web preservation and archiving is an important topic, and one that’s ever-relevant. But it’s all a little sad, too. I never wanted to break up in the first place. But like a bad boyfriend, Myspace made promises it couldn’t keep; fucking up everything we loved about it in the first place while punishing us for holding out hope. If Myspace said sorry and came back tomorrow in its 2006 form but with an easier photo-upload system, I would run back into its arms like nothing happened in the 10 years we were on a break. Until then, though, maybe it’s time for the emos to finally let go and grow up.