“Putin is an enemy of the people,” protesters chant across more than two dozen cities in Russia. “You’re not a tsar!” Police helicopters are right above our heads, and squads of riot police are using batons and gas, accompanied by the following message barked through loudspeakers: “Your actions are illegal. We’re going to use means of restraint.” We want simple stuff: democracy, fair elections, the freedom of internet, freedom to create art, to speak out and be wild, be different. We want respect from those we have elected to government — those we should be freely and fairly able to elect — and we want them to be accountable to us. Simple. For six years it was my dream to show up at a pre-inauguration protest, but when a stupid obstacle prevented me from doing that, I resolved that next time I’d be there. That stupid obstacle was prison. I wanted to be there on the 6th of May 2012, but that day I was in cell number 309 at the women’s prison facility number 6, Pechatniki. Putin was inaugurated on the 7th of May.

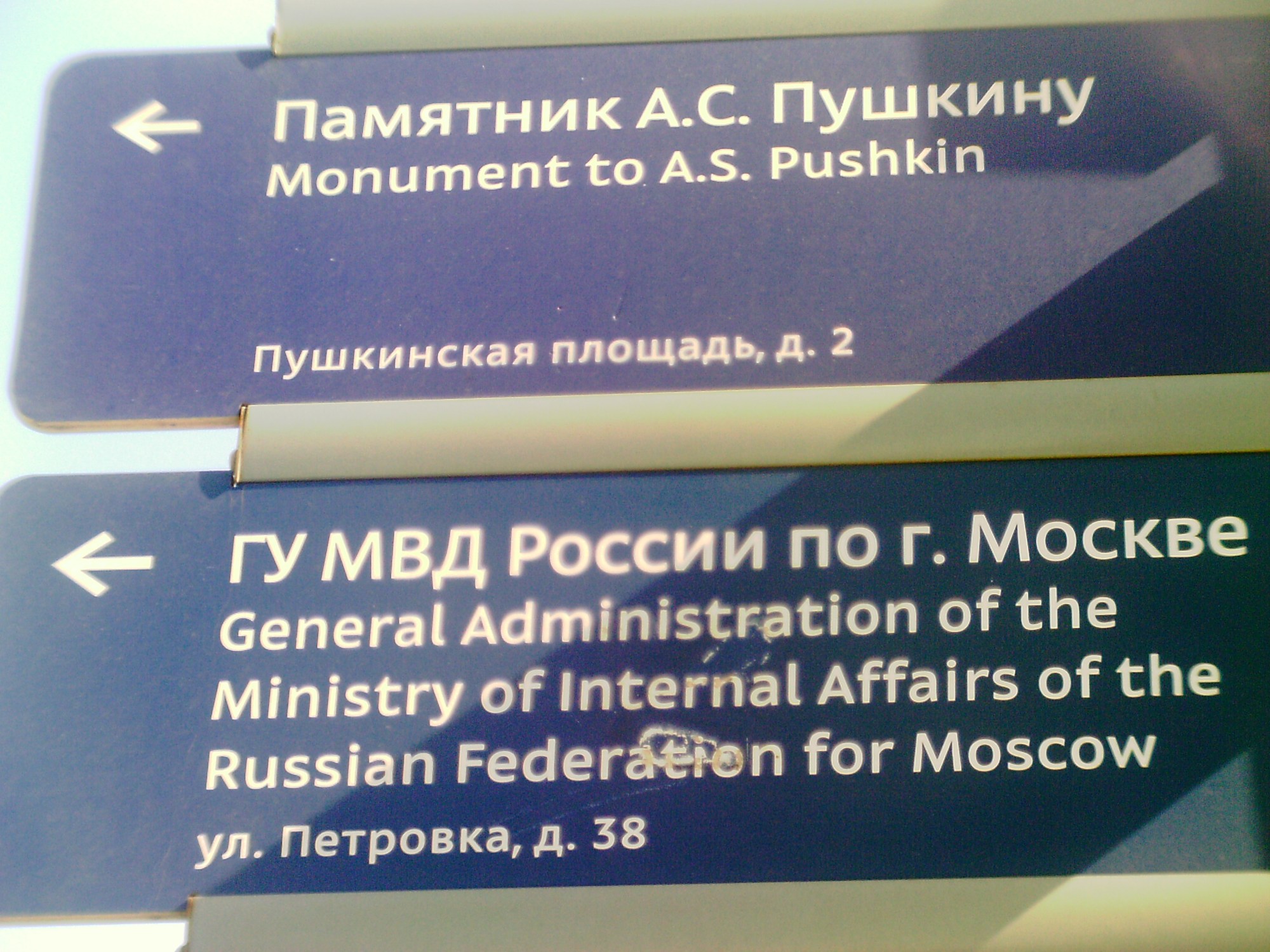

Events at public squares are good. You get a chance to see those who you’ve known for years. I’m at the Pushkinskaya Square in Moscow. A kaleidoscope of stories come to me through the faces there – stories that combine traumatic experience with hope. They’re about a struggle that seems endless. But this ongoing struggle is also about the dedication, commitment and strength that a human being is capable of. There’s something there that feels much greater, more enduring than the wins and losses of the day.

Eduard Rudyk is here at the square. A member of Moscow’s Public Supervisory Commission, he’s known in human rights circles as a fierce fighter for improving prisoners’ lives. We often forget that prisoners must have freedoms too. But Eduard doesn’t. Year after year he goes into prisons and argues with the wardens about how many potatoes a prisoner should get, how thick the blankets should be, how many prisoners should be in one cell — 40 or 95. When you’re in pre-trial detention, in lots of cases you can’t see your relatives because your investigator doesn’t want you to, so members of the Public Supervisory Commission become your family. When I see Eduard in the square I jump on him and squeeze him. Those who have never been a prisoner here couldn’t understand how passionately grateful you become to those who helped you while inside.

I see [journalist] Tanya Felgenhauer too, and hope she forgives me for not finding the courage to talk to her. I simply can’t figure out how to approach someone who has just been resurrected, Lazarus-like, and who went straight back to protesting. Tanya was stabbed in her throat in October 2017. “It did not feel like a stab, It felt like someone was cutting my throat,” she said the other day at the trial against the man who almost killed her. Tanya works at The Echo of Moscow, an independent radio station. She’s a vocal critic of the government.

There is no evidence that the assault on her was connected to the Kremlin, but it must be said that The Echo of Moscow’s staff have been targeted as enemies of the state by pro-Kremlin forces multiple times. The elites here often use vigilantes to intimidate and annihilate their opponents, it’s a preferred apparatus of the oppressive state. Some of my closest friends and I have been attacked a number of times by those vigilantes, and they always seem to be around when you’re keen to undertake an action. They are dangerous, because in most cases they’re not accountable for their assaults, since they’ve reportedly been hired by the government in the first place. I see a scar on Tanya’s neck – it was not just a bad dream.

Vigilantes are here today. Cossacks are whipping protestors. Another group of violent men in tracksuits attack some peaceful demonstrators who are holding colourful posters with rubber ducks on them — a symbol of protest [inspired by opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s report alleging that one of Russian PM Dmitry Medvedev’s opulent estates features a duck house at the centre of a pond]. People keep holding the damaged ducks and chanting: “Russia without Putin!”

Regimes of control are multiplying nowadays. If you’re arrested at a protest, you’ll lose more than just a night at the police department. Once you’re identified by law enforcement, you’re on the blacklist. That’s the turning point when the state begins its interference in your life. You may be detained by the FSB [Federal Security Service] at the airport when you’re trying to go on vacation with your family. You may lose your job, you may lose your place at college. Since 2012 the government have been fining demonstrators, so for some it has become quite expensive to take part in protests.

Kids between the ages of 12 and 14 are arrested in Moscow, Saratov and Chelyabinsk – in some cases violently. Last year, people of school age started showing up in the streets saying that they’ve had enough of Putin. “I lived all my life under Putin and I’m fed up. We want justice,” they chant. Their motivation is clear. Educational institutions, governed by the Kremlin, have turned against them and both the kids and their parents are being terrorised. “Shame! You’re growing up an enemy of the state,” they’re told, exactly as they would have been in Soviet times.

Standing in Pushkinskaya Square, I think about another protest that had happened here in 1965. Back then, 200 protesters gathered, their requests fair and clear: respect your own constitution (which guarantees freedom of assembly), follow your own laws and free the political prisoners. They were arrested, some of them expelled from universities. Mathematician Alexander Esenin-Volpin was here, writer and poet Varlam Shalamov, and Yuri Galanskov — a poet, who died in 1973 in Barashevo Mordovia prison camp, the same one where I served my sentence and went on hunger strike in the autumn of 2013. I’m not one who likes to make conclusions, but I’m committed to seeing parallels when they present themselves. Sometimes they speak to us, if we listen.

Like this? Read more on Nadya, Pussy Riot and Russia here.