Rineke Dijkstra has a way of speaking about her career as if it’s all been a happy accident, as if she’s simply been following some guide — she calls it her “intuition” — to rich pockets of subject matter year after year since 1990. Like the time when she tried to go clubbing at Cream in Liverpool, but the line was so long that she asked a cab driver to take her to another club, his choice. It turned out to be The Buzz Club, a disco filled with the teenage girls that inspired her mid-90s video portraits of dancing clubbers, The Buzz Club, Liverpool, UK/Mystery World, Zaandam, NL.

Even Dijkstra’s transition away from commercial photography, shooting portraits for magazines and company reports in the 80s, was sparked by an accident. She’s told this story many times: how while doing physiotherapy to recover from a bike accident in 1990, she decided to capture herself after swimming 30 laps, “when I was too tired to strike a pose.” Seeing the natural shape of her own body, just out of the water, led her to begin her most famous series to date, her Beach Portraits. Shot between 1992 and 2002, these epic near life-size images capture kids and teenagers — standing knock-kneed or proud but all seemingly guileless — on the seasides of her native Netherlands, the U.S., and Poland.

“What I always found difficult about working on commission,” Dijkstra says, “Was that people are very aware of what they want to show of themselves in a picture. And when they’re too conscious, they’re not themselves anymore. I wanted to capture something that was real. I always felt I had to get through a wall.”

Over the years, Dijkstra’s intuition has led her to photograph mothers with their babies after delivery, bullfighters just leaving the arena, a Bosnian refugee adjusting to a new life over the course of 23 years, and a young ballet dancer rehearsing for an audition. She captures her subjects in moments of change, where small cracks in composure let the light in. In March, the Hasselblad Foundation recognized Dijkstra with its prestigious annual award, and will display a selection of her work in the fall. Below, she discusses photographing youth for over 30 years.

How did your accident in 1990 lead to the Beach Portraits?

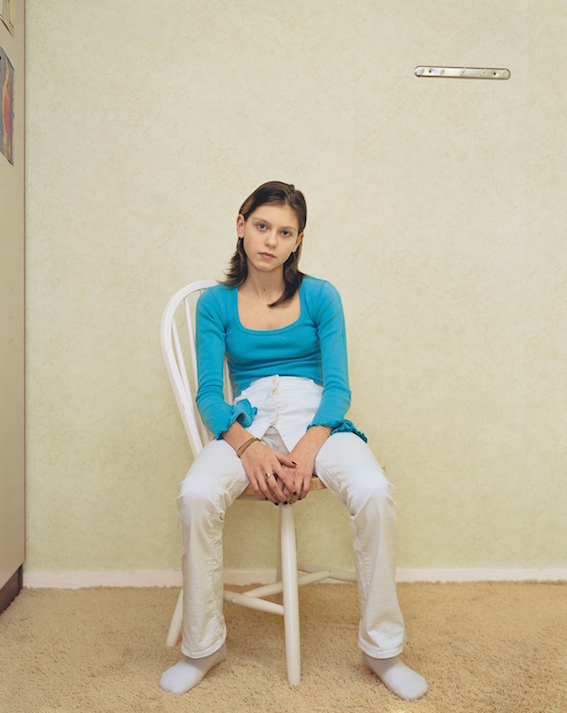

I grew up in a small town three kilometers from the beach. I was always intrigued by the fact that the sea appears in so many variations in light and color which made it look different every time I went there. After the self-portrait in the swimming pool, everything came together. I was fascinated by finding a natural pose and my previous interest brought me back to the beach; I started to make portraits of people in their bathing suits. First, I took a lot of pictures in The Netherlands. I didn’t just want to photograph young people. But one of my first pictures was of a 13-year-old girl — just at that age when childhood turns into adulthood — and that was quite beautiful. Later, a friend of mine invited me to Hilton Head Island in South Carolina and I took my camera. I realized how American culture differed from The Netherlands. Whereas the Dutch were very down-to-earth, and not very glamorous, Hilton Head was a wealthy family resort and it was all about body culture and glamour. I thought they read all these fashion magazines and wanted to look like that.

After that, I decided I’d like to go to Russia, because it would be the opposite of America. In the end, I went to Poland instead, and it was like going back in time. It felt like the 60s, from what I remembered from my youth. Actually, in Poland I realized that something else had to happen in my pictures; the fact that I wasn’t giving people much direction didn’t necessarily result in a good image. I needed another kind of tension, something in their pose or gaze, that distinguished them from others. I learned that could be hidden in the smallest details.

I started to photograph all kinds of people, but the children and teenagers represented a kind of uncertainty, their emotions were so much more on the surface. There was an openness. Older people already have a sort of fixed personality. With younger people it’s more flexible, everything is still potential. That space of being is not fixed yet, that’s what interested me.

Were there clear differences between the young people you photographed in the U.S. and Poland?

Maybe the Polish people were less self-conscious and more shy. It was 1992, around three years after the wall came down in Berlin, so there was still a very communistic feel. There was still a lack of fashion. They didn’t have MTV yet.

How did the young people you approached respond to having their picture taken?

Because I work with this 4 x 5 inch camera on a tripod, which looks like it’s 100 years old, people were sort of fascinated. Sometimes in Poland, people were super excited and they’d be a crowd of people around me. Working with this large format camera helped me to accomplish a kind of concentration; people understood this was not a snapshot.

How much direction do you give your subjects?

I am always looking for a natural pose, so I always talk to them and observe them at the same time. I try to bring them to ease and make them feel comfortable. There should be a moment when there’s a lack of inhibition.

Since you began Beach Portraits, teenagers have started to photograph themselves so much more, because of camera phones. Have you felt any shift in the way your subjects interact with you?

Maybe young people are more self-assured now, and less afraid of cameras. But it’s hard to say because I’m not from that generation myself. Yes, people take a lot of selfies now, but you never can really control your own image. Maybe people do know more what they look like now.

I love your video pieces of dancing clubbers. They’re like time capsules of the mid 90s but they also capture that universal feeling of losing yourself while dancing. How did you move into video work?

I had been photographing at schools for a project in Liverpool. My assistant and I were in our early 30s and we were really into clubbing. We’d heard about Cream in Liverpool and wanted to go but there was such a huge queue. So we asked a taxi driver to bring us somewhere else. He dropped us at The Buzz Club. It was really a club for 15-year-old girls! I’d never seen something like that before. They were standing in the queue for half an hour in only little dresses and no coats. I was totally intrigued by that. I thought I should just ask the manager if I could take photos. He said, Sure! I mean this was a long time ago, more than 20 years ago. I started to photograph people with a white background in a room at the back of the club. On the dancefloor, there was the music, people smoking, the DJ announcing birthdays — I couldn’t capture that in a picture. A friend suggested I try video. I had no idea about filming, but I bought a small Sony camcorder, which gave me new possibilities.

I like to work that way. You have to start somewhere. If you overthink everything, you’ll never do anything. I like it when ideas come from just working on something, there is always a lot of improvisation involved. When I had all the footage, I thought I should go to another club, in the Netherlands, and finally I worked with these so-called “gabbers” [Dutch hardcore techno fans]. The Buzz Club was all about the girls who were in charge, but the gabbers were mainly guys. They were really tough, and the club was absolutely not my piece of cake, but it was a good contrast. The piece ended up being a double-screened projection, describing the course of a night.

How cooperative were the gabbers?

They look pretty scary but they were quite nice. Though, after three o’clock I couldn’t work with them anymore because they were numbed by drugs and alcohol. I always had to go home quite early.

When you’re choosing your subjects, on a beach or in a club, what draws you to a particular person?

Authenticity. I like it when they have something which is original. It’s quite intuitive. It’s funny, when I made my second film, The Krazyhouse, I was already a bit older and I was so tired of working at night, so I did the casting at night and filmed in the daytime. Then one night I was so tired that I asked my assistant to chose people for me, and it really didn’t work. She’d been working with me for months and she knew what I was looking for. But it’s not about taste, it’s kind of a feeling. There has to be a click with somebody, some sort of understanding.

People often write about your work as focusing on people in transitional moments. Are you interested in wider political transitions as well as personal ones?

First of all, I am portraitist. A portrait is a carrier of emotions, ideas, and circumstances. That can be a young couple in a park, a girl dancing in a club, but also a Bosnian refugee girl in an asylum seeker center. I want to capture subjects in a specific state of being, I’m always looking for portraits that show a complex range of emotions.

Are you working on any new series?

I just finished a series about three sisters. Between each girl there is an age difference of seven years and I followed them and photographed them for seven years. It covers the ages of 4 through 23 so it covers childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. I’m also working on portraits of brothers and sisters together and how they relate to each other but also to their background.

How much do you want to know about your subjects and how much do you want to leave as a mystery even to yourself?

Making a portrait of somebody is intimate. You can come closer to a person, you can see emotions, and you feel like you can see everything. But you don’t need to know everything about somebody. With some of my subjects, like Almerisa, the Bosnian refugee whom I followed for 23 years, I have become good friends. Sometimes, subjects come to my openings, and it’s nice that these portraits mean something to them too. But the photograph, the image itself, becomes something on its own. It’s still that person but at the same time it’s abstract. What remains is the image, which speaks for itself. And if it’s a truthful picture, it makes you curious; you want to believe in it.

An exhibition of Rineke Dijkstra’s work will go on show at The Hasselblad Center in Gothenburg in October. The Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark will also host a show of Dijkstra’s work in the fall.

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson