Twitter is dead, Instagram is over and TikTok is toxic. But as the internet’s town squares set themselves on fire, young people are cultivating greener pastures over yonder, building a new wave of saccharinely-positive, non-toxic social media apps for Gen Z.

Though you may not have heard of many of these apps, their aesthetic hallmarks are easily recognisable. Their colour palette consists mostly of whatever Pantone’s colour of the year are, their imagery almost entirely bright, flashy photography. Text-wise, serif and sans serif fonts often appear in the same sentence. These apps promise ad-free safe spaces with compliments and rainbows and butterflies and tone indicators. They use buzzwords like “community” and “safe space” and seek to “empower” you. They function in a similar way to the millennial apps of yore, but they are targeted toward (even if not always founded by) Gen Z.

SUBSCRIBE TO I-D NEWSFLASH. A WEEKLY NEWSLETTER DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX ON FRIDAYS.

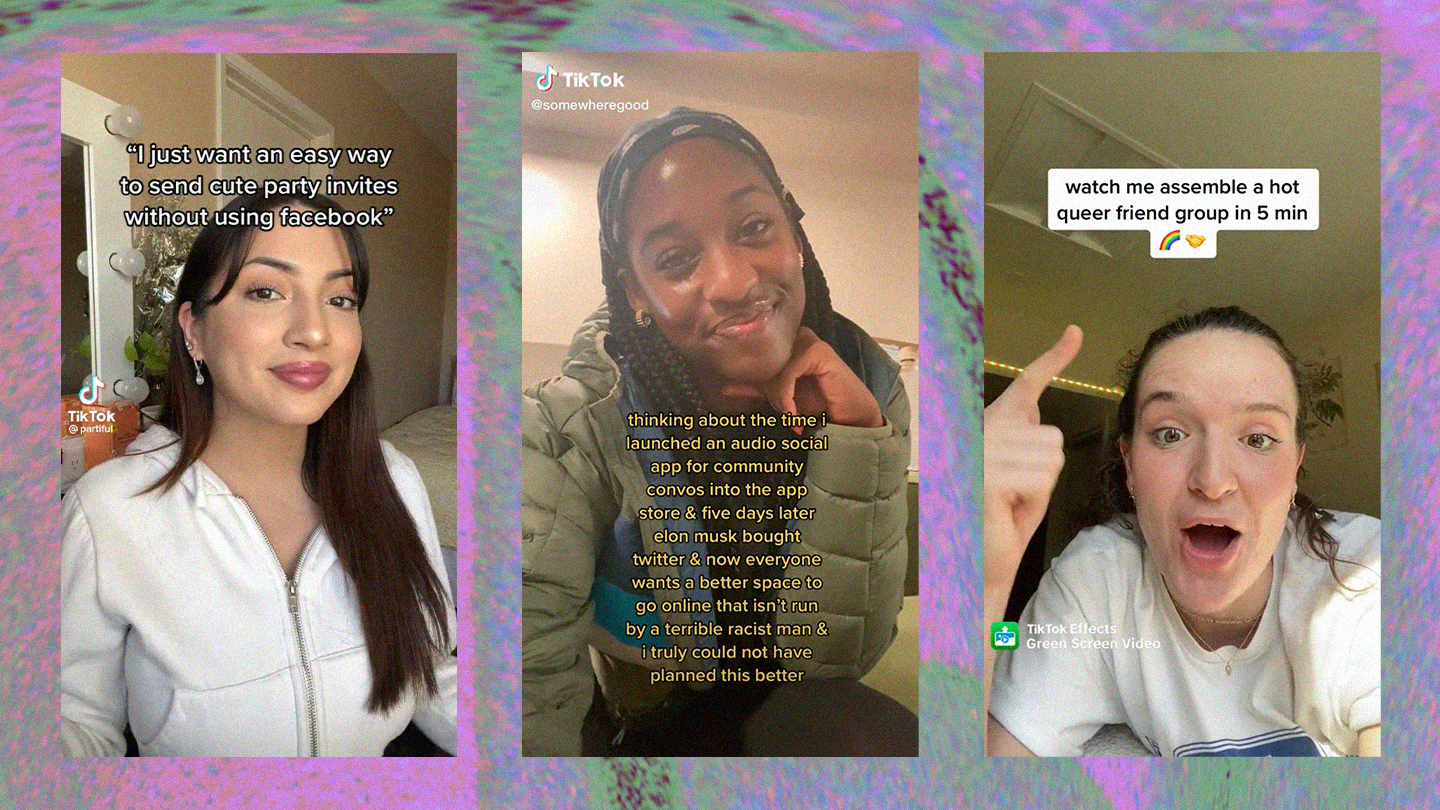

There’s Geneva (like Discord, but for the girlies), Diem (Yahoo Answers for womxn), Melon (Pinterest for “clean girls”), Pineapple (LinkedIn minus the cringe), Partiful (Facebook Events for hot people), OneRoof (Nextdoor for apartment buildings), Lex (Facebook Groups for local queer communities), and Somewhere Good (Clubhouse for people of colour). To quote Collective Media, a company that houses a few of these platforms, they aim to create an experience that “feels more like attending a party than performing on a stage”.

These actively non-toxic social platforms can be good for us: they have the ability to connect like-minded people who may not meet otherwise, create safe spaces for marginalised people and create a place for discussions on our most niche interests. Many of these apps brand themselves as facilitators for real-life connections, something we probably all need more of.

After exploring these apps, primarily Geneva, the general vibe (at least, of the promoted communities I’ve joined) was decidedly positive and non-toxic – almost uncomfortably so. Perhaps that speaks to how bad mainstream social media has become in the past decade or so; how we’ve all been interacting in the midst of a dumpster fire for so long that lush landscapes feel foreign. But, at the moment, these actively non-toxic social platforms feel like spaces for little more than small talk and pleasantries, with disagreement or productive discourse being against the norm.

As the antithesis to the culture of these major platforms, and the negativity and never-ending discourse that runs wild on them, actively non-toxic social platforms tend to be spaces where everyone agrees. This is not surprising given they are filled with people seeking out affirming online interactions in the first place, and the hyper specific design and messaging of these apps narrows down the pool of users even more. Thus the people who congregate in these spaces likely share similar backgrounds, political beliefs, cultural references and tax brackets. As opposed to a town square like Twitter, non-toxic social is defined by small social clubs.

That’s not exactly novel — communities of all sizes coexist on the internet, and with the increased use of spaces like Close Friends stories, finstas, subreddits, and Discord servers, most users seamlessly navigate between multiple online spaces and identities. However, as the major social platforms decay with no heir apparent, we are heading toward what The New Yorker columnist Kyle Chayka calls the “post-platform internet” — an internet beyond the dominant Web 2.0 ad-funded social media platforms. For now, actively non-toxic social may seem niche, but its rise hints at what the future of our online social interactions could look like.

The scholar Danah Boyd wrote in her 2014 book It’s Complicated that “social media enables a type of youth-centric public space that is often otherwise inaccessible.” In the years since, as the number of available IRL public spaces for teenagers to “just hang around” diminish, naturally they’re spending more and more time online. But where the internet’s town squares allowed them to come of age and explore the world, cottagecore social sells a safe space free of conflict — one that’s nothing like the real world. Alongside studies showing Gen Z partaking less in “risky” behaviour like sex, drugs and alcohol than previous generations, increasingly shrinking internet communities beg the question: How sheltered is too sheltered?

Mostly early- or growth-stage startups, these actively non-toxic social platforms are seemingly non-capitalist, with no obvious ads or requests for money. Instead running on venture capital, it means they don’t appear to have the grow-or-die mentality of startups of yore. But once (or if) these apps get big enough, they’ll then have to toe the line between function and monetisation — a main cause of the toxicity of Web 2.0. As long as the end goal — capital — is the same it’s hard to see how non-toxic socials can deviate from the big bad apps as they grow.

Maybe actively non-toxic social’s promise of “community” is just marketing-speak – the startup equivalent of “clean beauty” or “slow fashion” – but a non-toxic internet is a value proposition and just what the market wants right now. In its aim to be like “attending a party”, non-toxic social seeks to blur the line between spending time online and touching grass. But in reality, this would only lead us to spend more time online, something none of us need to do. After all, if being online feels too good, why would you come back to reality?

We live in a tech landscape that wants us to live our lives online — to stream and click and watch, to stay at home and order in and leave a big tip. In some respects, these non-toxic social apps are simply a continuation of the Silicon Valley impulse to app-ify and monetise micro-interactions like asking a woman a question, talking to your neighbours or inviting someone to a party.

As culture becomes more and more fragmented, so will platforms. We are moving from micro-influencers to micro-communities to micro-apps. We are moving toward a smaller, less offensive internet, at the risk of losing a view of everyone else. Perhaps the internet should not be entirely free of negativity, because the world is not free of negativity.

When we silo ourselves into smaller, more niche communities of people who are more similar to us, we lose perhaps the defining quality of social media – the ability to see a world other than our own. Time will tell whether non-toxic social becomes the next big thing, but perhaps the internet’s town square spaces are worth salvaging. We can benefit from an internet that’s more like the offline world: diverse, broad, and often contradictory.