You’ve probably never heard of Werner Kunz. However, if you were hanging out in 1950s Berne, Basel or Zurich, you might have caught a public screening of one of his notorious nudist films. And if you, unfortunately, resided in a Swiss canton where they were forbidden, you might have been transported to another by one of his censorship-swerving buses.

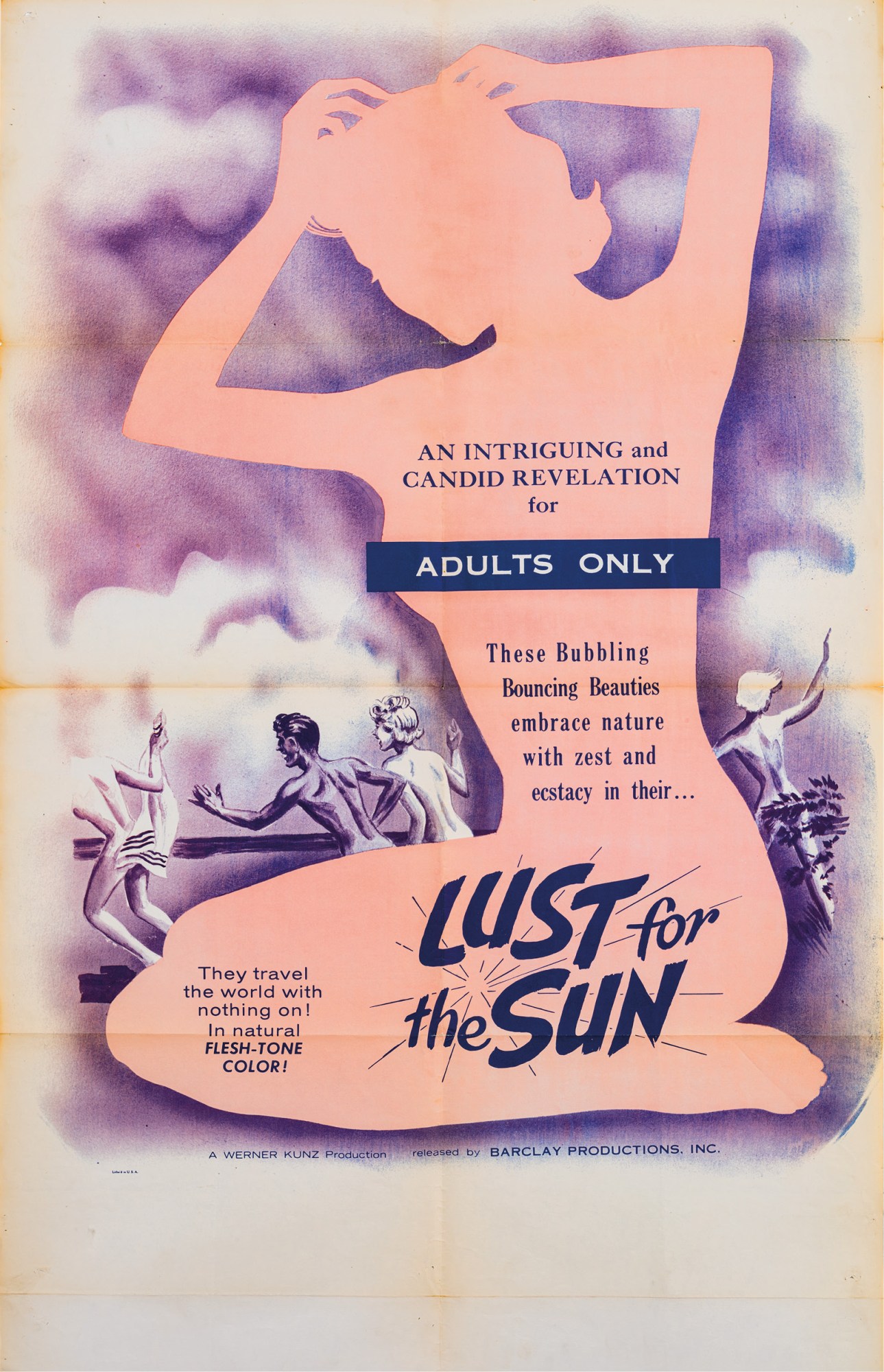

For one whole decade, Kunz had a de facto monopoly on nudist cinema around the world. The autodidact’s ground-breaking, globe-trotting films starred ridiculously beautiful, sun-kissed people playing sports and games on land and in water — in the buff all goddam day. Although offending the sensibilities of moral apostles in those prude days, Kunz’s films were the perfect antidote for a populace who desired escape and easy entertainment after the horrors of WWII. They made a huge splash abroad, camouflaged by the “documentary” frame as fruitful guides on travel, leisure and alternative lifestyles. But when Kunz was finally confronted with competing films of kinky and soft-sex variants, he disappeared into oblivion.

Enter Sonne, Meer und nackte Menschen (Sun, Sea and Naked People), a one-of-its-kind publication by film scholar Matthias Uhlmann, published by Edition Patrick Frey. Filled with scintillating sequences of film stills courtesy of the designer Manu Beffa, it certainly does what it says on the tin. The dust jacket even narrates an entire Kunz feature film with frames from almost every second. But beyond its visual splendour, the book is also a meticulously researched and instructive overview that closes what feels like a sensitive gap in Swiss film history and gives Kunz’s work the audience it deserves. The texts are in German, but don’t worry; we’ve got you covered. Here, author Matthias walks us through the life and work of Kunz: pioneer of sexual liberation on screen and “grandfather of all that stuff”.

How did Kunz get into making films professionally?

Having already made films as a high school student, Kunz perfected his skills in the strict school of Swiss amateur film clubs. He made his first commissioned films while working as a tour guide (mostly in Africa). After deciding to make filmmaking his profession in 1954, he kept this way of working at “Werner Kunz Film Production”. With an idea sketch for a story, he went on the road, sometimes accompanied by acquaintances and helpers, and handled the 16mm camera himself. He edited the material at home, as well as the music. He also wrote the commentaries and had them narrated by professional speakers.

Where did he find his actors?

For leading roles, he sometimes recruited, through acting agencies, actresses he met on location or who travelled with him for stretches. Sometimes his companions also acted (with or without clothes). On the shoots in the nudist colonies (mostly Héliopolis on the Île du Levant, France, or on the island of Sylt, Germany), anyone who wanted to was allowed to jump onboard. Of course, the operators of the areas exempted him from the strict film and photography ban that prevailed there since he was doing much to publicise the destinations.

I read Kunz’s production company was like a “one-man show”?

In Switzerland, he was unique in terms of the exploitation of his productions, for which he was solely responsible. In the style of the early travelling exhibitors, he refrained from using distributors, instead renting multi-purpose halls for screenings over the period of eight years. He placed advertisements in the newspapers and travelled with the films, projector and tape recorder in his luggage. Thus, he was also the booking manager and advertising manager, in addition to his central activity, filmmaking, of course.

What were Swiss attitudes towards nudity (in life and on the big screen) back then?

Organised naturism had existed in Switzerland since the 1920s. The magazine Die Neue Zeit was occasionally the subject of court cases because of the “lewd” images of naked people but was basically available to adults without any problems. Completely different rules applied to the medium of film. After sporadic and sometimes controversial screenings of nudist films in Switzerland in the 20s, they soon disappeared from the screens, and in the 50s, when Kunz appeared, the brief flash of a naked bosom or a “bed scene” (an unmarried couple together without further interaction) were the limits of permissiveness.

Kunz’s depictions of nudes in the moving image were, therefore, outrageous and promptly banned by most censorship boards (which, by the way, remained in some Catholic cantons until the early 70s). Interestingly, Kunz was lucky in the (Protestant) canton of Zurich, the cinema centre of German-speaking Switzerland. At the same time, as he was fighting for the release of his first film, Jules Dassin’s gangster film Rififi (1955) was also banned because of its depictions of violence. Both bans were then discussed in the cantonal parliament, which then certified Kunz’s film comparatively harmless. The ban was thus broken in Zurich, and his next films were allowed (although, in some cases, only after the removal of close-ups of bare torsos).

What did the old-school cinephiles think?

Those who sought “art” in the cinema were naturally disappointed by Kunz’s films and rejected the “superficial commercialism”, just as the morality fanatics condemned the “sinful trash”. Fortunately, this did not matter in the end. The opponents did not take action against the films on the streets. The interested people could enjoy the films undisturbed, while the disinterested ones did not spoil their pleasure, and that was that. What is decisive here, of course, is that the films indicate that those who allowed themselves to be filmed by Kunz had just as much fun as those who watched the films.

Was there an “are-the-films-art-or-not debate”?

Well, on the one hand, well-meaning contemporary critics praised the design of the films (especially the underwater shots), but criticised the sometimes long waiting times until he got to the “heart of the matter”. On the other hand, progressive reviewers welcomed the fact that his productions propagated the alternative lifestyle of the nudists. But basically, Kunz’s films were just that: “films”. As such, the status of proper artworks was denied to them; their subject matter, which was decidedly contrary to the canon, made matters even more difficult. There was never any talk of “art” in connection with Kunz’s films, and rightly so, since art is only that which an art judge ennobles, on the basis of its “value” and “usefulness” for the right conduct of life. That they gave pleasure to the audience seems to me far more important. And, as far as can be seen, they did so almost all over the world.

I heard John Waters is a fan!

In his autobiographical text Crackpot (1986), Mr Waters spoke rapturously of his favourite pastime during his teenage years in Baltimore: frequenting vaudeville theatres. “In between acts at some of the strip houses,” he recalled, “they routinely showed ‘nudist camp’ pictures, and I was profoundly influenced.” He subsequently listed five films of this “great genre”, which he declared to be “all classics of a sort”, and put in first place Nous irons à l’Île du Levant (1956). It is high time, I think, to inform the inclined audience (and preferably, of course, the great Mr Waters) that this film is the work of none other than Werner Kunz! Of course, I concur with Mr Waters’ demand for “a retrospective of nudist camp films anywhere in the world”, even though the chances of this happening do not seem promising in any respect…

By the way, after its US premiere in and around Philadelphia in May 1959, Isle of Levant played for years all over the country. The first run in New York lasted three-and-a-half months (as far as can be seen, by the way, in the same cinema where Deep Throat was to be shown thirteen years later).

I guess it’s difficult to identify one “great” Kunz film?

Yes. While in the case of Alfred Hitchcock, for example, one can certainly argue whether The Birds (1963) has more qualities than North by Northwest (1959), this is impossible in the case of Kunz, since they have not been shown anywhere for over 50 years.

Can I probe you on any personal favourites, nonetheless?

Sure! Firstly, there’s Gesunder Geist – Gesunder Körper (Healthy Mind – Healthy Body) from 1954, a 12-minute episode of his first film programme. It contrasts the lifestyle of an average man (weighed down by sins such as gluttony and alcohol consumption, who seeks relaxation in the sauna) and a female quasi-nudist (who extols her virtues of vegetarianism, swimming and gymnastics), exquisitely and factually filmed in black-and-white in 50s Zurich. At the end of the film, so to speak, the man goes into the light. Now in colour, he is converted, eats a frugal meal on the Île du Levant and then contentedly exercises in a “cache-sexe” (nowadays known as the “G-string”). This film is the prime example of Kunz’s early solutions to avoid censorship. And the audience learned something valuable while seeing something “spicy” along the way!

My second favourite is Naturisten im Schnee (Nudes in the Snow) from 1959. The 10-minute presentation of communal winter sports activities in St. Moritz etc. is followed by the equally long main part: three “female students” arrive at an alpine hut in the Bernese Oberland, where they take off their clothes and frolic in the snow, build a snowman and go sledging. A thoroughly surreal film experience! This work, by the way, was a special case for the highest Swiss court, which took the view that the presentation of nudists on the beach in their traditional habitat was to be tolerated, while their activities in the snow exceeded the limits of what could be tolerated.

That’s so bizarre! So there were more acceptable climates for nudity on celluloid? What were the arguments of the censors?

When Kunz argued that nudity was tolerated in painting and sculpture, they emphasised the comparatively direct film effect in the dark movie hall. And when he pointed out that nudism was not forbidden, they countered that this only applied to the private sphere. Imagine what would have happened to the medium of film if they had taken this principle seriously and only allowed in movies what was also permitted in reality…

The censors’ last refuge was the construction of the “average man” who would reject nudism, which is why its cinematic representation should also be banned. Maybe it’s just me, but I at least have never met an “average person” in the true sense of the word.

So, why did Kunz subsequently disappear into oblivion?

The main reason is surely that the serious study of “unserious” films has only become respectable in recent years. The canon of “normal” entertainment works have been the subject of research for some time, but there is still a need to catch up when it comes to cinema at the margins.

As for Kunz himself, I assume that he did not seek fame. Pushing himself to the fore did not seem to be his thing. Moreover, as a prudent businessman, he kept control over the copies of his films whenever possible. This is probably why he refrained from giving his films to a public film archive. Whether such an institution would have done anything useful with them is, of course, another question. But Kunz was by no means shy or bashful. He looked forward to the book about his work with some pride. I very much regret that he did not live to see it published.

On that note, what would you say Kunz’s legacy is?

With a shout out here to Max Nosseck’s 1954 US nudist film Garden of Eden for the sake of completeness, Kunz can be considered the inventor of the nudist film in the post-war period, or, as he said of himself: “the godfather of all that stuff”. His films contributed decisively to a shift in the censorial boundaries and thus to a liberalisation of commercial film.

It must be emphasised that his films are consistently of a positive nature, from my point of view at least. Kunz never ever debased people in his films, and he never deceived the audience (if one does not hold against him some overly full-bodied promises in his advertising campaigns, which are part of the game). He only presented “Nature” at its best. In this, he was an honourable gentleman (or, if you like, committed to nudist thought). This in no way precluded financial gain. From 1954 to 1968, he tirelessly delivered nudist films, long and short, always intent on offering the audience something of high quality on the one hand and something novel on the other. He succeeded in this until he was overtaken by the soft-sex films for which he had paved the way. In 1970 and 1973, he produced two “erotic comedies”, and then he called it a day.

‘Sonne, Meer und nackte Menschen (Sun, Sea and Naked People)’, authored by Matthias Uhlmann and designed by Manu Beffa, is published by Edition Patrick Frey.

Credits

All images courtesy of Imperial Film AG, Zurich and the Estate of Werner Kunz.