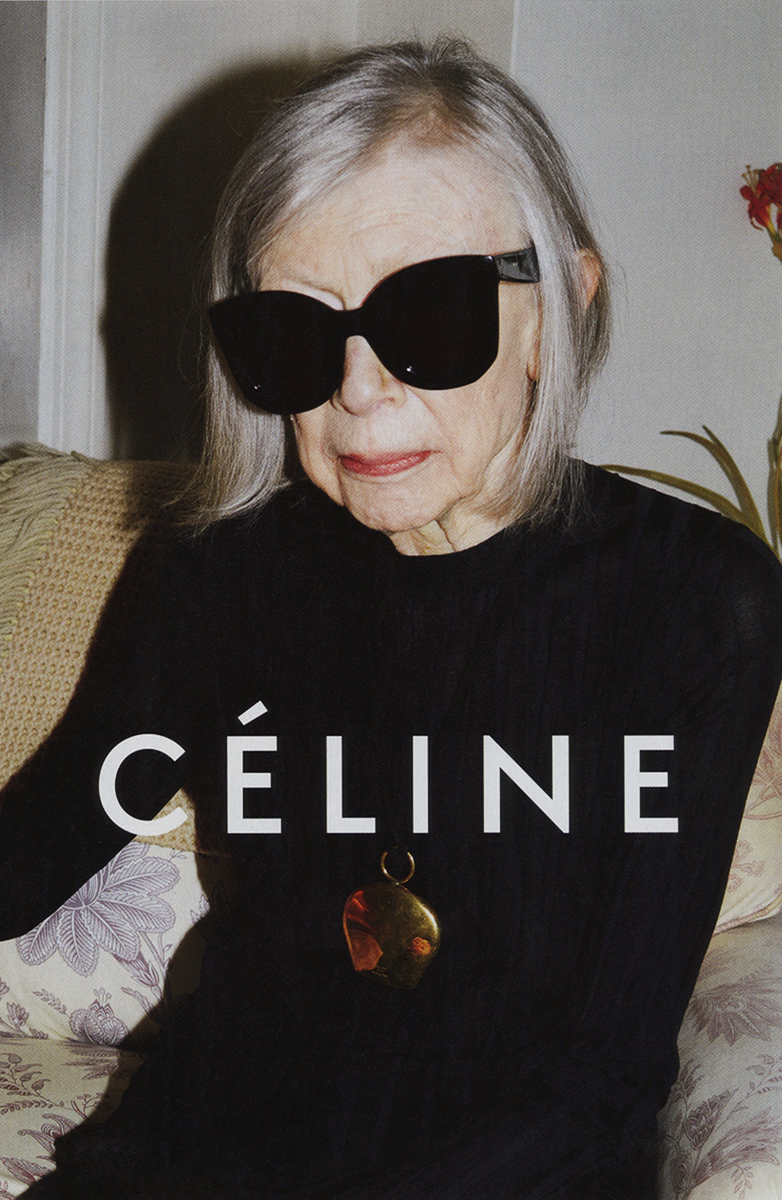

In a fashion advertising landscape dominated by images of teenagers, it was a momentous decision. It was also sublimely apt. If Céline is the minimalist distillation of modern, empowered femininity, then Joan Didion – author, journalist, saviour of the American confessional – is its natural poster girl. Her miniscule frame emblematic of so much that we now take for granted as being part and parcel of American culture. Her prose, a master-class in paucity taught to literature students around the world.

Fans and detractors of Didion’s cool and measured prose will at least concede on one thing: Didion trades in sentences. Faultless clauses, as she says, describing the work of her main influence, Ernest Hemingway: “they’re perfect sentences. Very direct sentences, smooth rivers, clear water over granite…” Her wizardry, in my opinion, lies in revealing the latent power of words by placing them in a carefully constructed, simple, order. Pretenders have faltered while Didion soared to global stardom and became a style icon in the process, though it is not as accidental as some commentators would have us think. Stories published in the last few days would do better than to cast Didion as the nerdish WASP with an incidental flair for dressing. She did, after all, work at Vogue for a good portion of her twenties and has enjoyed a long and reciprocal friendship with the fashion world. Today images of her stood next to a white Corvette Stingray are reblogged ad infinitum. Something which Phoebe Philo, creative director at Céline, is no doubt aware of.

While it is difficult to imagine that the decision to use Didion wasn’t made with her Tumblr currency in mind, this collaboration has at least created something new and noteworthy. Perhaps its greatest triumph is the continued employment of Juergen Teller. Whose consistently brilliant work hits new, respectful and honest levels. Despite his meteoric career, Teller’s humility is still evidently intact. Not since Julian Wasser’s portraits of Didion in 1968, shortly after the publication of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, have we seen a photo distil so successfully the author and her writing. Yes, Didion is a waifish literary giant with amazing cheekbones, but thanks to Teller’s gentle, coercive eye we also get something of her subtle humour. She is sardonic, at times disdainful and in the latter part of her life, understandably morose, but she is forever in control of the tone.

The sublime interplay between her solemn expression and the uncompromising grace of the Céline typeface is a work of carefully orchestrated advertising trickery. This is much more than a celebrity sponsorship. It is a direct assault. Are you going to be shaped in the image of other ads, a mawkish wimp, enslaved to the trappings of vanity, or are you going to do as Didion and the pared down Céline woman does, and strive for something more?

It’s deceitful perhaps, given that all of this is going on within an ad. But then that’s what we’re looking at after all. Philo must be applauded for her decision to use Didion without explanation. Why should Justin Bieber’s deal with Calvin Klein afford such an immediate furore, and not the appointment of one of the world’s leading writers by one of the world’s leading fashion houses?

The tsunami of Internet activity by fashion people with literature degrees in the immediate wake was grating; Intellectual Twitter rearing its head to discuss an author for the first time because they happen to have been anointed by a French fashion house. Still, it is great to see Didion reclaiming her place as boss. Following the tragedy that plighted her later life, she has understandably shied away from the press. Apart from the promise of a documentary being made that she is supposedly assisting with, she has kept a low profile. With any luck, this playful appearance will bring with it renewed interest in her writing and new recruits to the church of her disciples, whose fervour can only be explained away by passages like this:

“We are not idealised wild things. We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves”

– from The Year of Magical Thinking

Credits

Text Nathalie Olah