When artist Pacifico Siliano’s parents separated back in 2010, he received a Polaroid of his Uncle Frank — the first photograph he had ever seen of his father’s brother, who died from complications of AIDS in December 1989. “I remember thinking this is such a strange gift to be given by father,” Pacifico says of the picture of a dapper young Frank Silano decked out in a coat and tie, living his best life in New York. “At the time, we were becoming estranged — my father didn’t ‘agree’ with my life because I was gay.”

Just three years old when Frank passed, Pacifico had no memories of his uncle. “This felt like a really special object because there was only one photo of him,” he says. He hung the Polaroid on his studio wall, where it served as a beacon of his journey through both life and art. Coming of age in the 90s and early 00s, he understood the fears many held as a result of state, church and media-sponsored homophobia during the height of the AIDS crisis.

“It was a scary time for gay men; although there was treatment, there were people dying, and that impacted my ideas around my sexuality and the kind of life I could have,” Pacifico says. “I grew up terrified of sex. I thought if you were gay and you had sex, you are going to get AIDS and die because that was the ingrained homophobia that existed in the culture at the time. I just remember it was like, ‘Your uncle was gay and look at what happened to him.’ It wasn’t until the 2000s, when I became an adult, that I could begin to navigate those complicated ideas around sex, shame and queerness.”

As Pacifico came of age, art became a space to ask questions both sacred and profane, and to look for answers where once there had only been questions. Over the years, he searched for other photographs of Frank to no avail. His uncle, like so many other gay men of the era who contracted HIV before treatment became available, was all but erased in death.

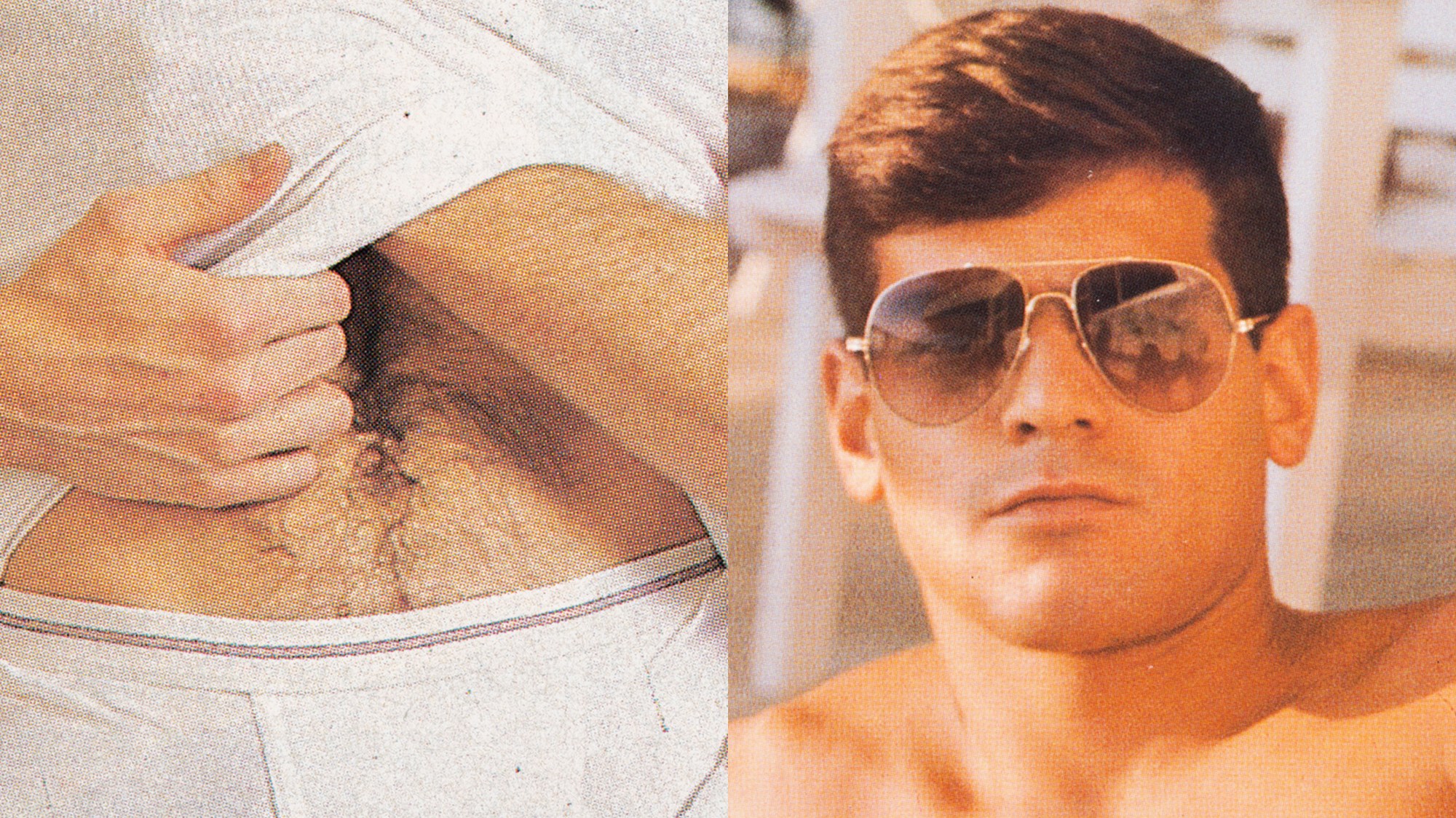

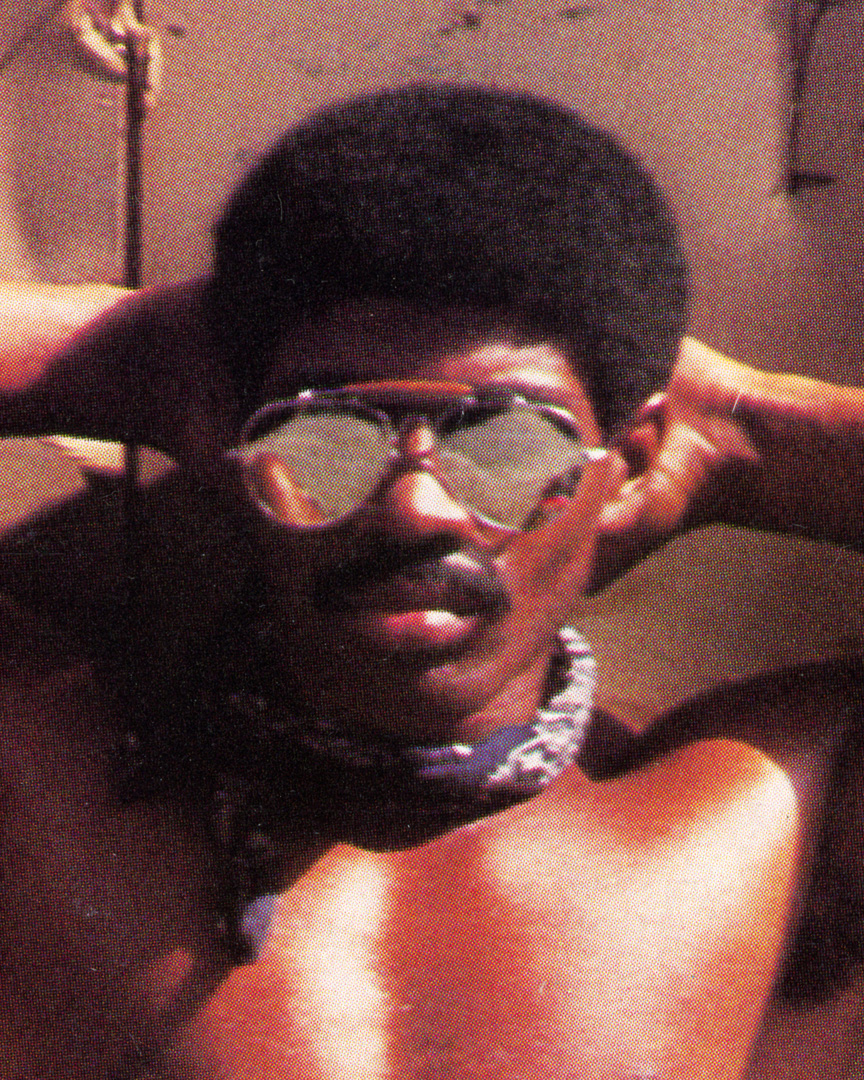

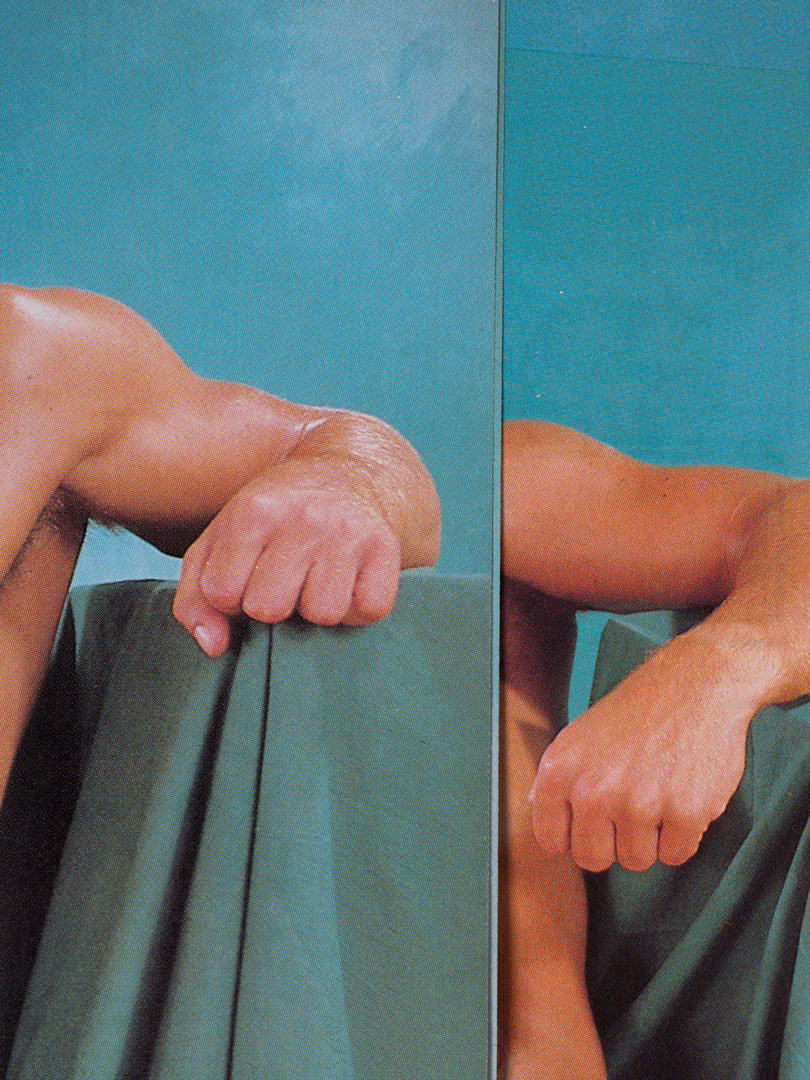

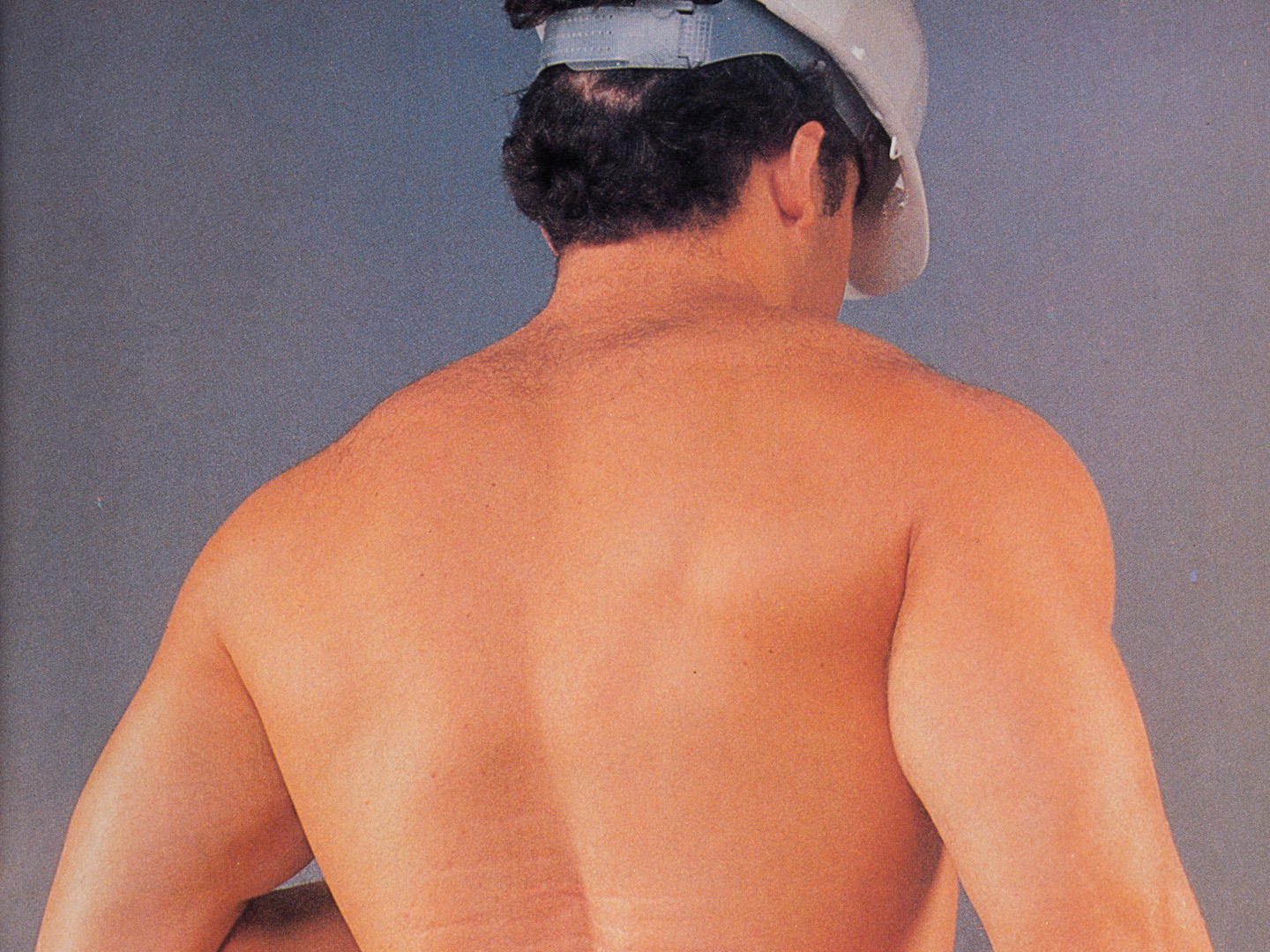

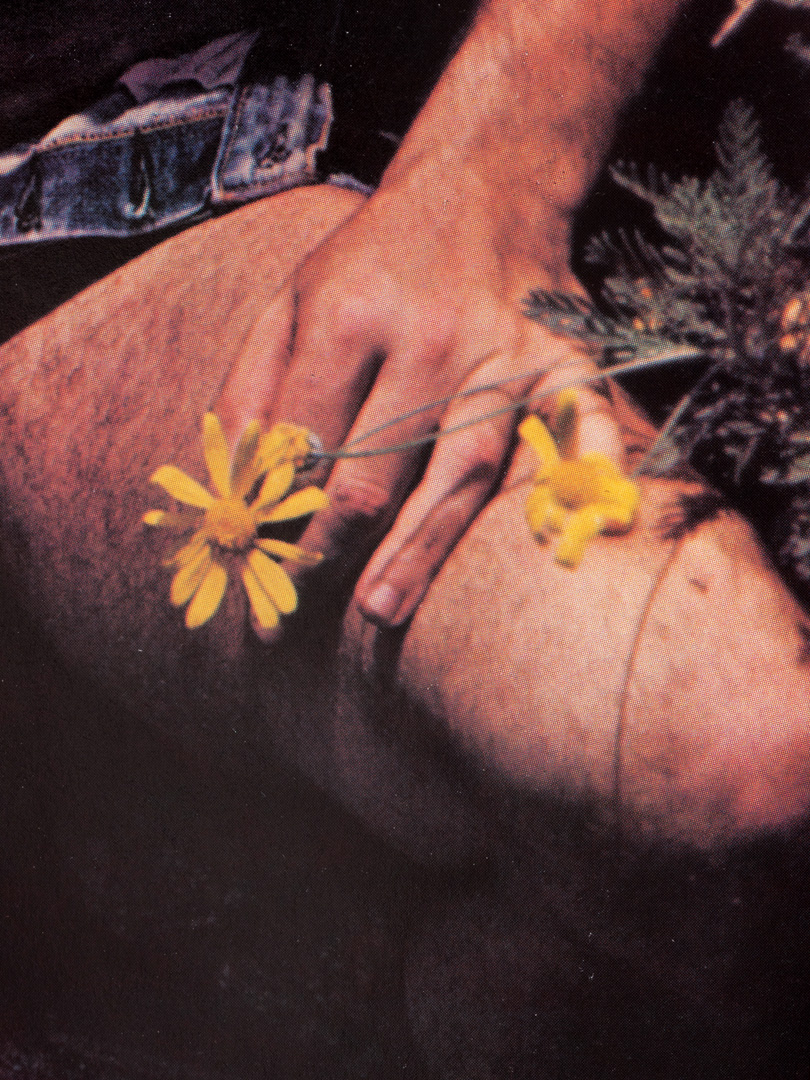

Although he couldn’t create a portrait of Frank, Pacifico realised the only way he could comprehend the man he never knew was to assemble a pastiche of images of gay men drawn from archival materials from the time. He began perusing the pages of softcore gay porn magazines from the 70s and 80s, like Blueboy and Honcho, that flourished soon after full-frontal male nudity was finally legalised in the United States.

As fate would have it, Pacifico’s work echoed in the void, bringing Frank back to him in ways he could have never dreamed. His uncle’s partner happened upon a 2012 article Pacifico wrote for TIME, which featured the Polaroid of Frank as the lead image. “He was thinking about Frank, decided to Google search his name, and that came up,” Pacifico says. “We spent hours FaceTiming, and he sent me all these pictures of Frank, which was really special because I got a more fully realised portrait of who my uncle was. Because you’re gay, your family doesn’t quite know you like your chosen family and your friends do. I feel forever grateful that it brought us together.”

Recognising the power of archival images to bridge generations and explore longstanding archetypes of gender and sexuality, Pacifico explored the connections between past and present in new and revelatory ways. “I always think that the photograph is this slippery, non-fixed thing that’s constantly moving so that our understanding of a certain time and place is always subject to reevaluation,” he says. “The medium of photography is regenerative; something new is happening and evolving, and that’s incredibly rewarding for me.”

With his work in two new exhibitions — Sweetest Kill, a solo show curated by Monti8, and When I am Empty Please Dispose of Me Properly., a group show curated by Jenny Gerow — Pacifico continues his evocative explorations of masculinity and LGBTQ identity, nostalgia and iconography, and the bittersweet yearning for a love long gone that fills the heart with a curious mixture of melancholy and warmth.

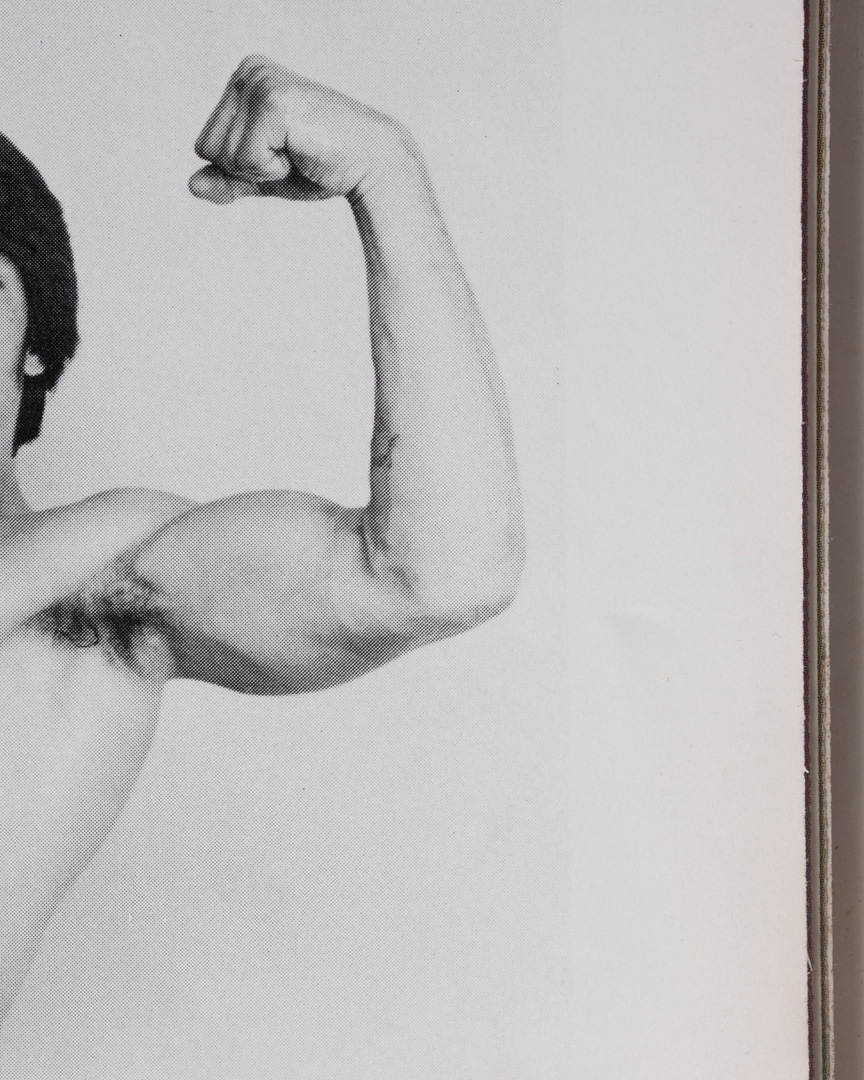

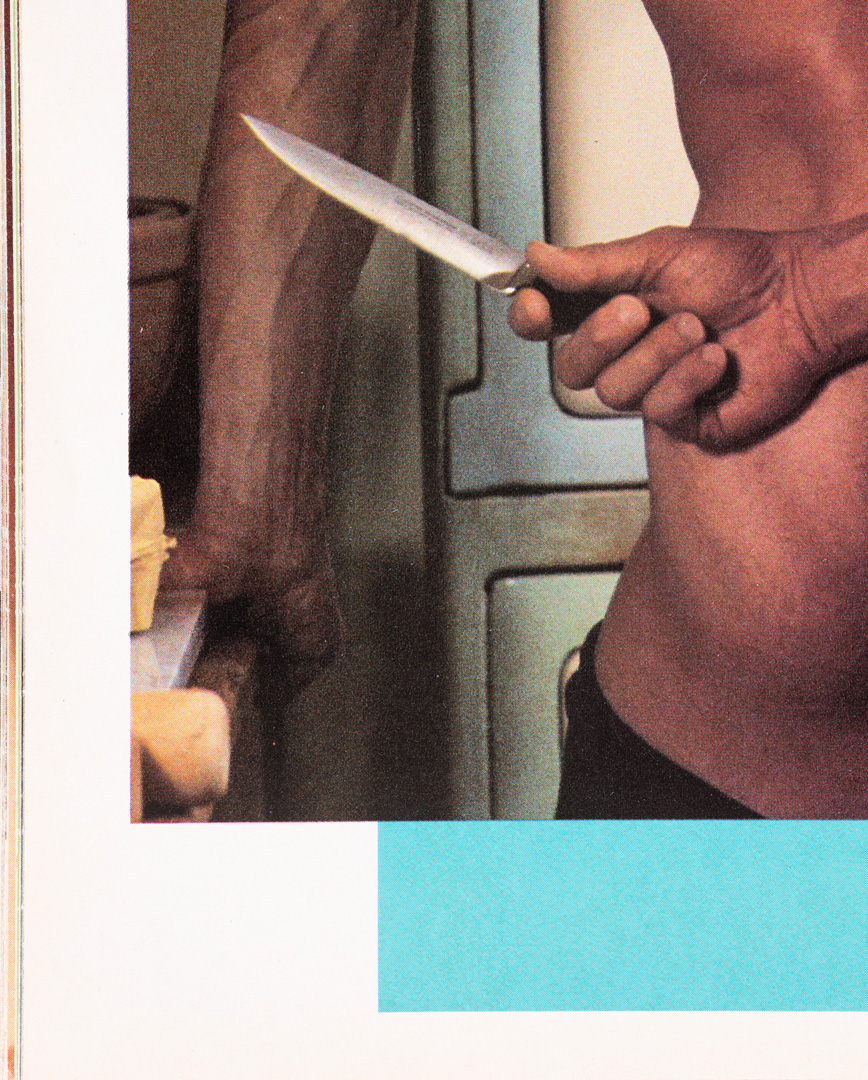

While much of Pacifico’s earlier work around HIV/AIDS was about loss and longing, about desire and dreams unfulfilled, as seen through the gentle visions of manhood, his new work confronts more complex histories where the boundaries of sexuality and gender become blurred and intertwined. “Looking at the uncertain times that we live in and the violent rhetoric people have on the internet, and in the real world, it’s very much tied to whiteness and America,” he says, referencing male archetypes like the soldier, biker, construction worker, hunter, bodybuilder, cop, cowboy, or athlete that proliferate the pages of gay porn.

Pointing to the symbols of American masculinity like the black leather jacket, blue jeans, white undershirt, cowboy hat, and motorcycle that actors like Marlon Brando and James Dean popularised nearly a century ago, Pacifico taps into our collective consciousness to reconsider our unblinking faith in iconography. “There’s a thin line between subversion, transgression, and reifying an icon; it’s a delicate dance. I’m pushing myself in new directions that frighten me, looking at my own masculinity, and making myself uncomfortable by asking how do I play a part in the system?”

“The work I am currently making lives in a grey area that’s not neat. It’s not a condemnation, nor is it glorifying it. It’s both seductive and sinister. When I say ‘sinister,’ I’m thinking about how unhealthy and dark these archetypes can become because it’s about the fetishisation of power. I have a new piece I’m excited about: a bare-chested man with machine gun shells all over his chest from a round of ammunition. Part of the fantasy is that it could turn into danger at any moment, and that’s exhilarating. The longer you sit with the image, the more complicated it becomes because it’s about the stylisation of power that often happens within the gay community.”

Pacifico seeks to use art as a tool of subversion, a beautiful object that lures us close, only to capture us in its relentless challenge to conventional beliefs promulgated by the status quo. He speaks of his work as a “Trojan horse,” echoing the words of Chinese-Afro-Cuban cubist painter Wifredo Lam (1902-1982), who used art as a weapon in the fight for liberation. “I wanted with all my heart to paint the drama of my country,” Wifredo once said, realising he could “act as a Trojan horse that would spew forth hallucinating figures with the power to surprise, to disturb the dreams of the exploiters”.

Peeling back dazzling and dreamy layers of flesh, Pacifico quietly interrogates ways in which power structures insinuate themselves in every corner of our lives, making the personal political by trying to imprint and thereby implicate us in its designs. As we make our way through an era fraught in every regard, Pacifico confronts difficult questions that lie in the eye of the storm, taking solace in the knowledge that change is the only constant in the world.

‘When I am Empty Please Dispose of Me Properly.‘ is curated by Jenny Gerow and on view 25 January–30 April 2023 at BRIC in Brooklyn, New York. ‘Pacifico Silano: Sweetest Kill‘ is curated by Monti8 and on view 18 February–April 2023 at Susi Hub in Latina, Italy

Credits

All images © Pacifico Silano, courtesy of the artist