This article originally appeared on i-D US.

When Paris Is Burning was released in 1991, it introduced Harlem’s drag ball culture to the world and ushered phrases like “throwing shade” into our cultural lexicon. But the documentary also ignited a lot of controversy when director Jennie Livingston was accused of voyeurism and exploitation.

Nearly 30 years after its original theatrical release, a 16mm digitally remastered version of the iconic film is coming to the big screen once again. With its return comes a chance that the controversies could be reignited, but Livingston says she isn’t too worried about it. “The internet can weaponize people who have feelings,” she says, sitting in a meeting room at the New York headquarters of the film’s distributor, Janus Films.

“Hopefully, if there are conversations, they can be constructive and there can be civility. If people really think it’s a damaging film or a badly made film, okay, that’s how they feel,” she adds. “If they think it’s a good film and it’s a film that did good, you know… Let’s parse how problematic it is to make any film, let’s parse that in all of its complexity.”

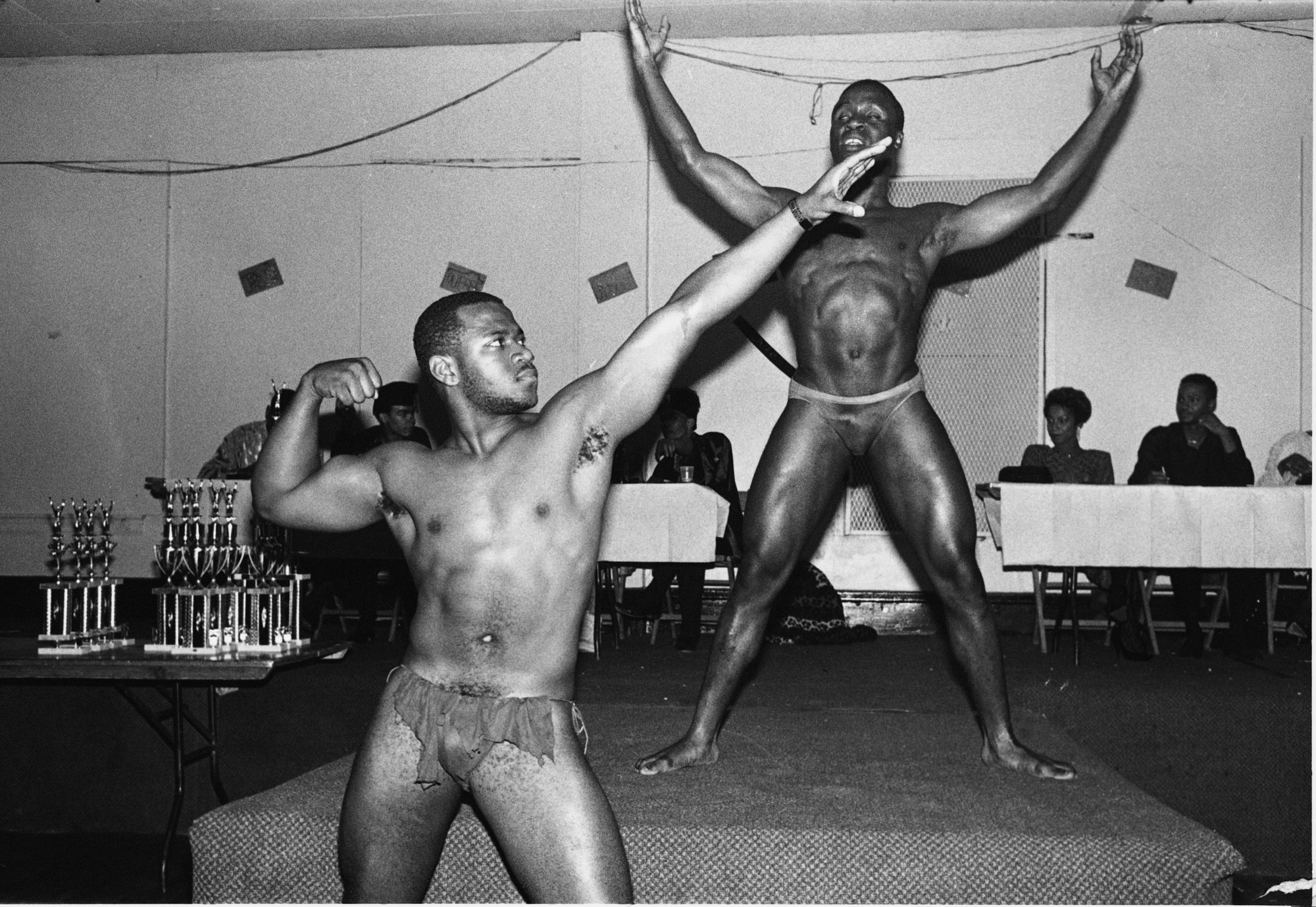

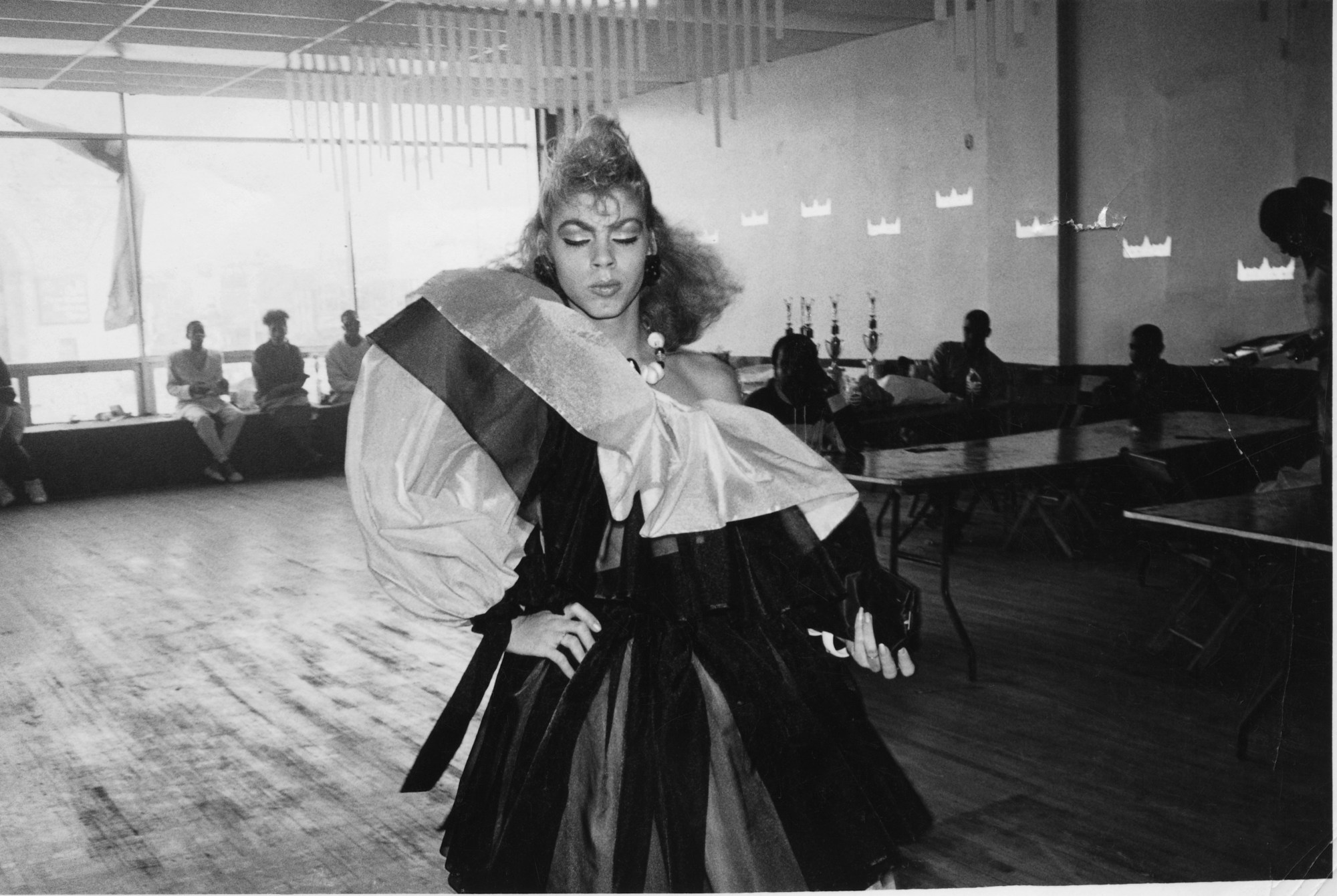

For the past 28 years, Livingston has had to defend herself for documenting a community, mostly made up of African American and Latinx gay and transgender performers, that she (a self-described “white, Ivy-educated Jewish kid”) didn’t belong to. Made over seven years in the 80s, the film provided a snapshot of an inspiring, resilient community, their fierce voguing competitions, and the camaraderie and creativity that sustained them. It also helped Livingston realize her own queer identity. While Paris Is Burning is considered an influential film, it’s also started heated debates about appropriation and privilege.

One of the complaints about Paris was that it focused too heavily on tragedy – much of the documentary shows the performers talking to the camera about homophobia, transphobia, racism, AIDS and poverty, with the film ultimately ending with the revelation that one of the performers, Venus Xtravaganza, was found murdered in a hotel room.

Livingston defends her decision not to end on a lighter note. “We had to think a lot about, you know – if you just make it really upbeat and fun, that’s a lie, because people are struggling. But if you make it all struggle and drugs and AIDS and death, that’s not really respectful either, because the balls are sustaining, they are amazing. So we tried to be realistic.”

Following the film’s release a number of the subjects also attempted to sue for a cut of the profits. Ultimately the suits were dropped, but the producers still distributed $55,000 to 13 members of the cast.

“The truth is, there was nothing deceptive in the making of the film. If it feels unfair that people in the film didn’t get paid, well, that’s kind of how every documentary is. We did pay people something, because we said we would. We made a sale, we took some of the money and we gave it to people in the film,” she says. “The idea that I got rich and they didn’t? Well, first of all, I didn’t get rich. And second of all, you do want filmmakers to make some money. Filmmakers can’t exist if we don’t get paid at some point.”

Paris’s original release was handled by Miramax, which was helmed at the time by Harvey and Bob Weinstein. Livingston says her experience working with the producers (who are now facing criminal charges for years of alleged abuse) was “slightly toxic,” citing an issue with a trailer they’d made. She had asked them to remove a clip of Venus because it “would have been disrespectful to her trans identity,” and says that they then pulled the whole trailer and created “a super-boring promo reel with just silhouettes and critics’ pull quotes.” “I’ll never know for sure why they did that,” she wrote in the film’s press notes, “but it felt like retaliation for my having exercised my contractual right to have a say in how the film was promoted.”

Now, Livingston is working on the critically acclaimed TV series Pose, which is a dramatized take on the same world Paris documented. A consulting producer since season one (“which basically meant I encouraged them to hire diversely,” she says), she is also directing an episode for the third season. She’s excited because she’s “been trying to direct episodic for 15 years.”

“Soon after Paris Is Burning was released I was having these experiences where it was very hard to get a second film, and I wasn’t ever short of ideas. I would have meetings, but the funding doors weren’t open. I’d talk about it and I remember this producer told someone I knew, ‘Oh, she has a real chip on her shoulder.’ And I was like, ‘No! I was talking about my reality!’” Fortunately nowadays there’s not only more discussion about the inequalities in film and TV; there’s a tangible drive for inclusivity. It could be argued that Paris, with its portrayal of iconic drag artists, helped get us there.

Livingston says she still regularly gets people coming up to her to tell her the film encouraged them to be themselves. She recalls a gay man approaching her at Sundance Film Festival a few years ago. “He was like, ‘I grew up in a small Texas town, and your film helped me realize there was a life for me outside of my town.” That’s who I made the film for!” she exclaims. “Everybody doesn’t have to love it, everybody doesn’t have to love you, everybody doesn’t have to resonate with the ball world. But the fact that it has an impact and does some good and means some things to some actual human beings – that’s all you can hope for!”

Paris Is Burning screens at Film Forum in New York from Friday, June 14, and at Landmark’s Nuart Theatre in Los Angeles from July 5.