This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Earthrise Issue, no. 368, Summer 2022. Order your copy here.

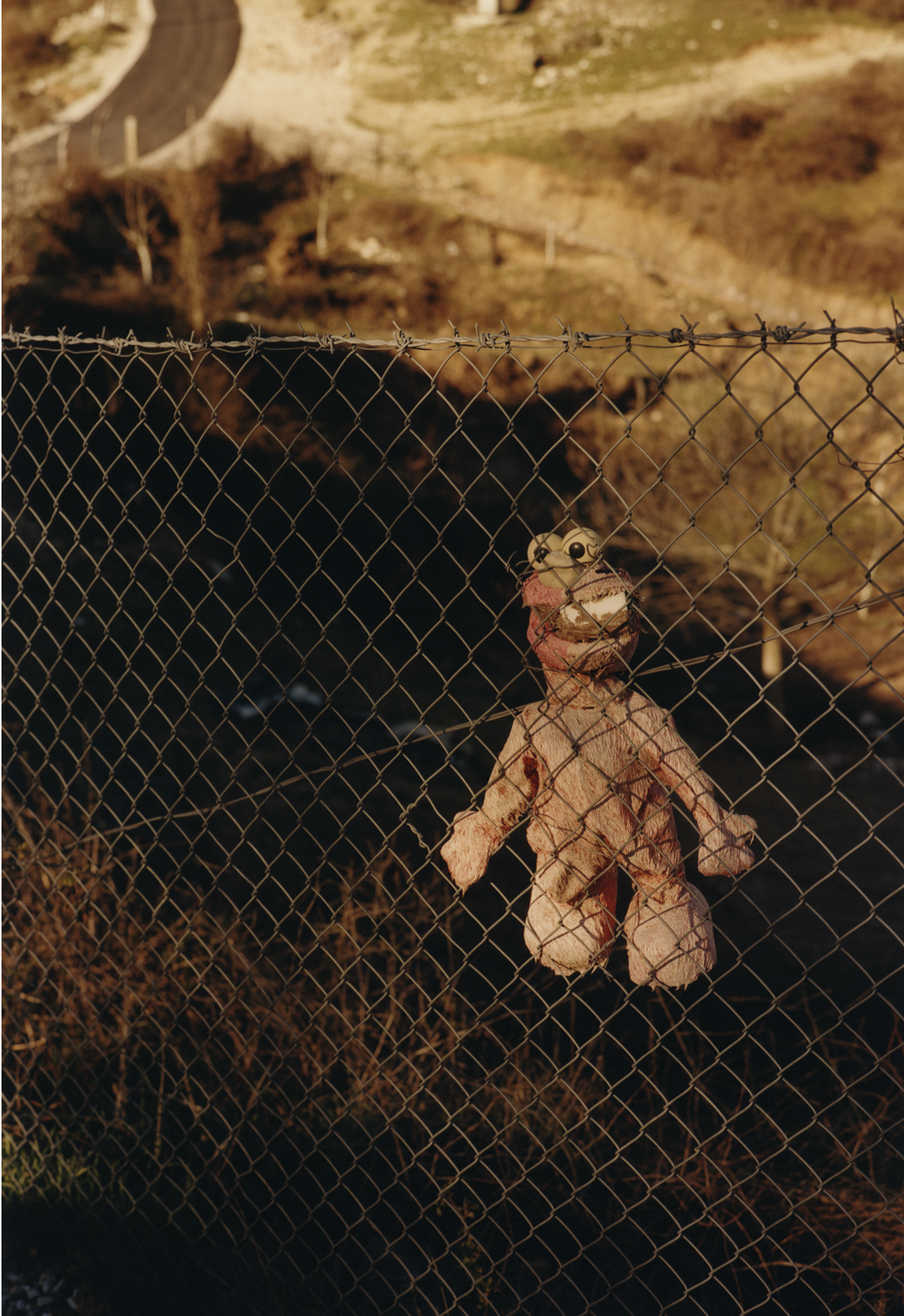

Today the construction of 3,400 hydropower dams is threatening the last wild rivers of Europe, across the Balkan Peninsular. Working alongside the ’Save the Blue Heart’ coalition of NGOs, outdoor apparel brand Patagonia is fighting to save them. This story captures one of these rivers, the Vjosa in Albania, and features Patagonia items that have been previously worn and repaired through the Worn Wear programme.

By the late 1980s, the outdoor apparel company Patagonia, co-founded by husband and wife team Yvon and Malinda Chouinard almost two decades earlier, “was prospering but losing direction,” says its director of philosophy, Vincent Stanley. What had started as a makeshift climbing equipment shop, based out of a tin shed in Ventura, California, was on its way to becoming the $1bn company that it is today, with its products as ubiquitous on urban commutes as they are on hiking trails.

Patagonia’s graphic label depicting the El Chaltén mountain range is by now an anti-fashion symbol of sorts; loved by everyone from outdoorsy dads to fashion folk and hypebeasts. Its visual campaigns over the years have left an indelible mark. Who can forget that New York Times Black Friday advertisement telling readers ‘Don’t buy this jacket’, or the infamous flying baby from the 1995 issue of the Patagonia catalogue?

Yvon co-founded ‘1% For The Planet’, in 2002 with Craig Mathews (Blue Ribbon Flies) – a business alliance whereby all members pledge one per cent of sales to the preservation and restoration of the natural environment, and through which Patagonia has awarded over $145 million in cash and in-kind donations to grassroots organisations. However, Patagonia wanted to further improve its responsibility credentials.

“Until then we had seen ourselves as too small to make a difference environmentally in the way we produced,” says Vincent, who has worked for Patagonia on and off since its inception. The company then began studying every step of its production line, introduced third-party audits, became a founding member of the Fair Labor Association and hired a director of social and environmental responsibility.

Then, in 2007, in an effort to be more transparent, Patagonia launched the Footprint Chronicles – an interactive website that traces the social and environmental impact of its products. “It changed our relationship with the suppliers,” Stanley explains. “Initially they were reluctant to talk about problems publicly, especially regarding production. But we found that the suppliers loved it when we worked with them to solve issues. And pretty soon they were coming to us wanting to be featured on the Footprint Chronicles.”

“We decided the word sustainable was illusory, that we are not sustainable, and everything we do as a company is to minimise impact.” Vincent Stanley

As a writer and poet, Vincent – who in 2012 co-authored the book The Responsible Company with Yvon Chouinard – is scrupulous in his choice of words when discussing Patagonia’s environmental efforts. “We decided the word “sustainable” was illusory; that we are not sustainable; everything we do as a company is to minimise impact,” he says. “Responsibility involves a sense of agency, of saying ‘OK, this is what I’m doing, and I am responsible for it. I can make improvements or I can continue to persist in problematic behaviour’.”

“The primary responsibility writers have is to keep language related to the senses and to experience,” he continues. “The environmental crisis is no longer something that’s going to happen, we’re in the middle of it. And if we are going to solve it we’re going to have to be awake, we’re going to have to use language that speaks to one another rather than the language that is designed to keep people asleep and stop them from questioning what is being said.”

By encouraging consumers to think more deeply about the purchases they make, and demonstrating the power and responsibility brands have to raise awareness around environmental issues and climate change, Patagonia has inspired companies to follow suit.

In 2012, Patagonia achieved B Corp certification – a designation that the business is meeting high standards of verified performance, accountability, and transparency, based on factors from employee benefits and charitable giving to supply chain practices and input materials. It was the first Californian company to do so, and beyond its products the company has become an important platform for environmental activism.

In 2018, the company formally started supporting an initiative to raise global awareness around Save the Blue Heart, an ongoing campaign to protect the last wild rivers of Europe – the Balkan Rivers, located in southeastern Europe between the Black and Mediterranean Seas – from an onslaught of 3,400 planned dams. The campaign focuses on the Vjosa river in Albania, the Mavrovo National Park in North Macedonia, and the rivers of Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Part of Patagonia’s partnership was the production of a feature-length documentary, Blue Heart, in 2018, followed by the short Vjosa Forever, in 2021, which traces the fight to save Europe’s largest wild river and ultimately declare it a National Park – the first of its kind in Europe. Among the activists and environmentalists interviewed is Ulrich Eichelmann, the Vienna-based founding CEO of RiverWatch, a society for the protection of rivers. “Dams destroy everything that characterises these rivers,” Ulrich says. “It’s like blocking the arteries in a body. Even though people consider reservoirs to be beautiful because they look like lakes, below the surface it’s more comparable to an underwater desert.”

Dams and their consequential eradication of rivers have the obvious effects of destroying the aquatic life that call those rivers home. If the Balkan dam projects were to go ahead, nearly one in ten of Europe’s fish species would be pushed to the brink of extinction.

Then there’s the wildlife that depends on these water systems, that will be disturbed by dam and road construction. The Balkans, for instance, is home to critically endangered endemic species the Balkan lynx, which has an estimated total population of around 120, with as few as fifteen individual animals remaining in Albania. There is also, of course, the vital role rivers play in storing carbon by transporting decaying organic material and eroded rock from land to the ocean.

People have a tendency in their conservation efforts to forget themselves in the equation, further divorcing themselves from nature. But one thing Blue Heart captures so beautifully is the communities who are inextricably linked with the rivers, and the cultures that could ultimately be lost along with them. It is a fate Ulrich is all too familiar with, and the reason why the campaign to save Europe’s rivers is so personal to him. In the opening scenes of Blue Heart he recalls how, as a young boy in Germany, he would catch trout with his bare hands in the river where his father learned to swim, then one day a dam was built up-stream and the water stopped flowing.

In the race to find alternative sources of energy to fossil fuels, hydropower is often depicted as a clean alternative, but as Ulrich explains this couldn’t be further from the case. “Hydro is one of the worst sources of power in terms of its direct impact on nature,” Ulrich says. “Because there are so many dams, you can be 1,000 kilometres away from one and you feel its impact. Most people think they have seen a free-flowing river in Europe, but they haven’t.” Because there are so many elements that go into making a dam, from its construction to the roads required to get to it and the trees that need to be felled to construct those roads, hydropower is open to corruption. And for as long as the various parties involved are making a profit, they will want to maintain the industry’s green image.

Geothermal, solar and wind are all better options according to Ulrich, both in terms of efficiency and environmental impact. But it isn’t just about finding new sources of energy, it’s about reducing the amount we use. “We’re just talking about producing more energy in different ways, but there’s no way we can replace the amount of fossil fuels we are currently using,” he says. In 2021, Earth Overshoot Day – which marks the date when humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year – fell on 29 July, meaning that we are using almost twice the resources that the Earth has to offer.

Although there is a significant amount of work to be done, the Save the Blue Heart campaign as a whole is helping to move things in the right direction. Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama, President Ilir Meta, and Environment Minister Mirela Kumbaro, have given their public support for the protection of the Vjosa river, declaring in separate statements that they are in favour of creating a Vjosa National Park – closing the door on any hydro plants being built along it. Meanwhile, the construction of the Kalivaç dam, which would have destroyed this unique river system forever, was rejected by the public authorities.

Besjana Guri, communication officer at EcoAlbania (an NGO founded as a joint initiative of professors of the Department of Biology of University of Tirana and the Save the Blue Heart of Europe team in Albania) emphasises the socio-economic as well as the environmental value a Vjosa Wild River National Park could have: “If Albania has the first wild river national park in Europe, there’s an opportunity to develop ecotourism and local economy. In recent years, many young people have been leaving because they can’t find work and don’t see a future here. If we manage to protect biodiversity and in turn help the community it could be the most sustainable development for Albania.”

“A rivers is like a tree,” Besjana adds. “If you cut off the branches it dies and it is the same with rivers, if you don’t protect the tributaries then you’re not protecting the main river itself.”

Through the fog of eco-anxiety Blue Heart provides a small beacon of hope for the positive influence brands such as Patagonia can have by spotlighting important environmental issues, and the power we as individuals possess in preventing ecological disasters. In one particularly moving scene towards the end of the film, we witness how a group of women, many of them mothers, stop a hydropower plant being built on their river in Fojnica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, after occupying the road for 325 days. As one of the interviewees in the film concludes: “You don’t need to be a biologist or a scientist if you want to be a nature conservationist. You just need to be a human with a voice.”

P.S. We are happy to announce an update to this amazing campaign since the magazine went to print. In Tirana today the Albanian Government took the historic step of signing a commitment to collaborate with Patagonia and experts from the Save the Blue Heart campaign on the establishment of a Vjosa Wild River National Park. This will ensure the protection of its pristine nature and help develop a nature-based economic future for local communities. It is one step closer to protecting the Vjosa forever. Europe’s last big, wild river.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more from the new issue.

Credits

Photography Colin Dodgson

Text Liam Freeman

Fixer Nick St.Oegger

All clothing Patagonia Worn Wear