Growing up in Lorient, a small town on the western coast of France, Patrick Cariou came of age playing beach volleyball before going pro in 1980 at the age of 17. The tall, handsome country boy moved to Paris, dedicating the next four years of his life to the sport before growing weary of the highly constricted life of a professional athlete. While visiting his family on summer break, he had an epiphany while paging through a fashion magazine: he would become a photographer. It was as simple as that.

In just one week, Patrick’s entire life had changed. “I got lucky right away,” he remembers of his big break: a job as a photo assistant at Pin’up, the biggest rental studio in Paris. In a short time, Patrick became a well-known fashion photographer, moving in circles that included Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, and Peter Lindbergh, and shooting for Vogue Hommes International, GQ, and ELLE when the glossies reigned supreme.

Young, talented, and self-assured, Patrick thought he knew it all. Then his friend gave him a book by Paul Strand, and his whole world was turned upside down. Perusing the work of the highly influential modernist who helped elevate photography to the pantheon of art, Patrick had a revelation: “The photography book is the way,” he says, with a nod to the work of luminaries like Paul, Edward S. Curtis, and Ansel Adams.

Before the explosion of desktop publishing in the late 90s, the photo book was extremely rare — a feat achieved by true devotees who dedicated themselves to long-form projects that took years, if not decades, to complete. With the photo book as his North Star, Patrick found purpose and meaning by forging his own path, preferring the independence and self-determination of its pure artistry over careerist norms.

In 1985, he embarked on Surfers, chronicling one of the world’s most anti-authoritarian sports. Searching for the perfect wave, Patrick travelled among the nomadic tribe of athletes to the far corners of the earth, creating a timeless vision of the renegades who built their lives around nature rather than the reverse. Using a medium format camera, Patrick crafted a series of classically composed portraits, action scenes, and landscapes that evoke the dynamic spirit of 19th-century adventure novels and majestic works by Romantic painters like Eugène Delacroix, J.M.W. Turner and Théodore Géricault.

In 1993, Patrick moved to New York with one goal in mind: to find a book publisher. He arrived in the city long before gentrification destroyed the multi-generational communities that formed the heart and soul of the city’s fabled street culture. He remembers the mid-90s as a golden age when a wide array of people could still afford to live and work in New York. “It was definitely one of the best times of my life,” he says.

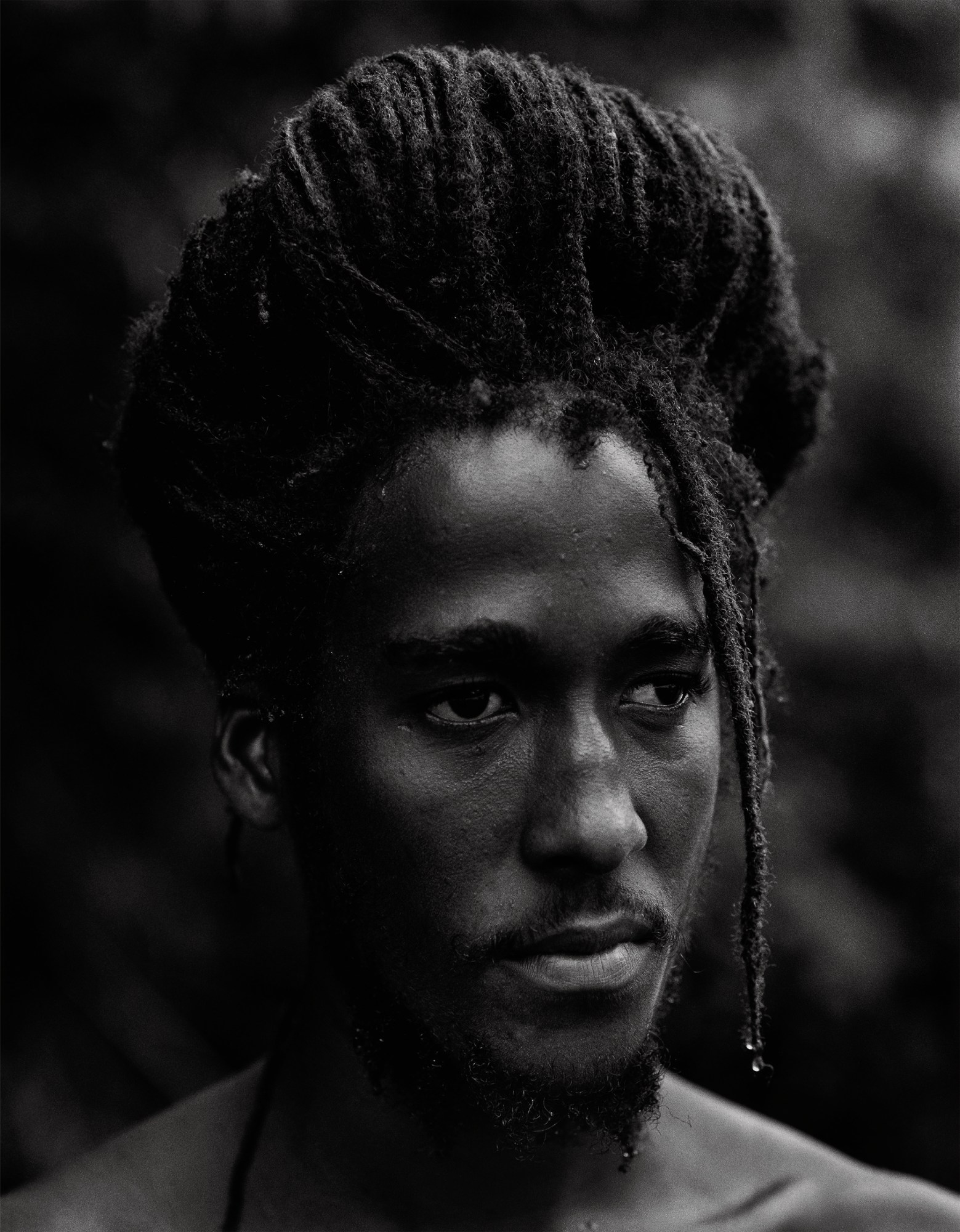

Soon after arriving in the city, Patrick embarked on his second project: a two-volume series about Jamaica that would showcase the Rasta and rude boy communities that have shaped global music, style, and culture since the 1970s. But after being shot at in the West Kingston neighbourhood of Trenchtown, Patrick was forced to re-evaluate his plans. He then headed into the mountains searching for the Rastafarian brethren who were forced to leave Pinnacle, the original settlement founded in the 1940s by Leonard Howell.

Located in the hills north of Spanish Town in St. Catherine, Pinnacle was home to Rastas who rejected white supremacy and British colonisation, known as “Babylon”. They turned to nature and to scripture for guidance and saw the future in Ras Tafari Makonnen, who was crowned Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia in 1930. Although they were treated as outcasts, the colonial government still viewed Rasta community and culture as a threat, raiding and destroying Pinnacle and committing Howell against his will to an asylum.

With their home destroyed, the Rasta brethren relocated to Dungle, a waterfront slum on the outskirts of Kingston — but the government continued its persecution campaign, razing their homes once again and driving the Rasta back into the hills. It was here, in the 90s, that Patrick encountered the descendant of Pinnacle living at one with nature for Yes Rasta. “They were surprised to see me,” he remembers. “There were some people who said, ‘No way, get the fuck out.’ But after a few trips, I started presenting myself as an artist and showing them pictures. I spent a lot of time with them, days, even weeks. I felt like I was leaving luxury to experience something really rare.”

By the late 90s, Patrick connected with a small independent publisher, powerHouse Books, which was then just a couple of people working out of a half a loft on Varick Street in Soho. He published Surfers in 1998, then Yes Rasta in 2000 to critical acclaim and modest commercial success. But Patrick wasn’t done. He remained obsessed, and when the hand of fate struck, he was ready to take the leap. A chance encounter with someone at a Jamaican restaurant in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene soon led to him returning to Kingston and working on this third project, Trenchtown Love.

“Trenchtown is really small; it’s just a few blocks,” Patrick says of the community, which was first built as a housing project to replace the West Kingston squatter camps destroyed by Hurricane Charlie in 1951. Organised around a central courtyard with cooking and bathing facilities, the one and two-storey concrete “knog” buildings became home to the city’s Rastafarian community. The birthplace of rocksteady and reggae music, the neighbourhood soon reached the world stage as artists like Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Bunny Wailer became the voice of a generation.

During the 70s, Trenchtown became embroiled in violent clashes between the People’s National Party and the Jamaica Labour Party, with war breaking out on its streets and the community divided into gang territories. “As this transformation took place, the archetype of the Trenchtown resident also changed; the spiritual Rastaman, the ‘sufferer’ stolidly enduring in ‘Babylon’, was replaced by a different model, the authority-flouting, gun-toting, fearless ‘rudeboy,'” journalist Eddie Brannan wrote in the introduction to Patrick’s third book.

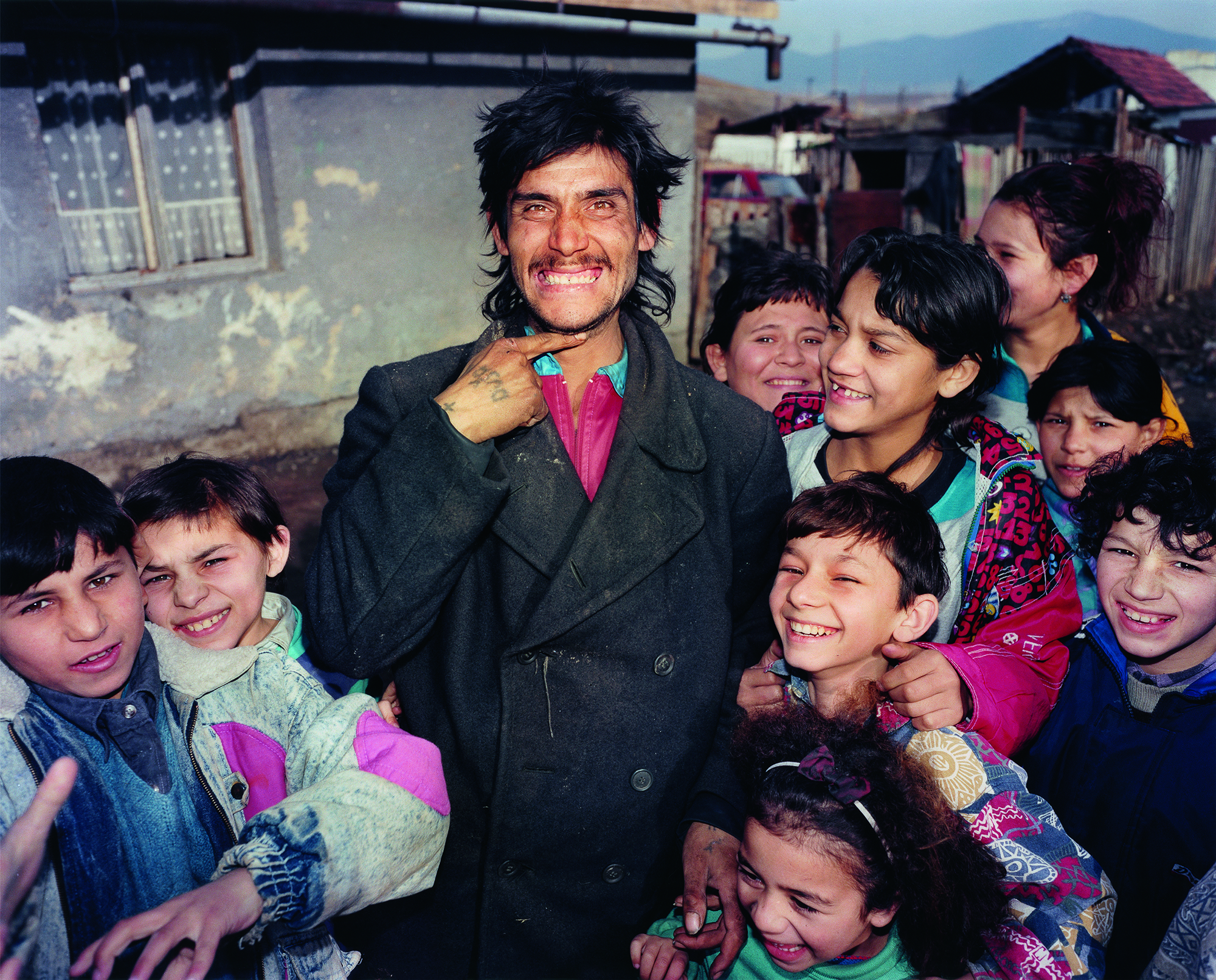

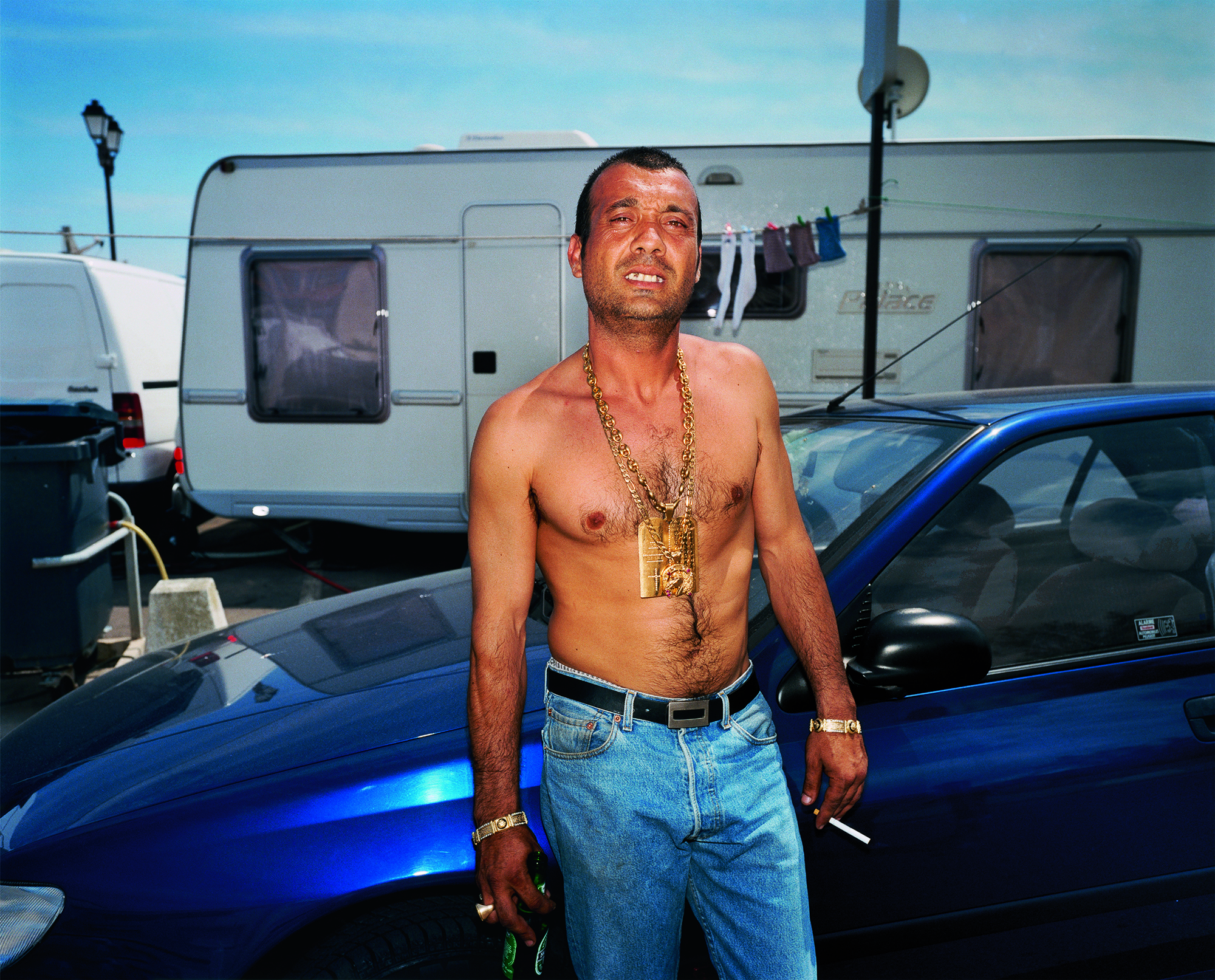

With the proper introductions, Patrick was able to enter Trenchtown and spend time with the people of the community just as he had done with the Rastas on the hillside. With the recent publication of Patrick Cariou: Works 1985–2005, Patrick revisits these bodies of work, plus his fourth and final book, Gypsies, made travelling around Slovakia, Romania, Turkey, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Taken together, Patrick’s work offers a mesmerising journey around the world in search of the divine, offering a timeless portrait of people living on the fringe, creating life on their own terms.

Unlike many outsiders who travel to far-flung communities as an extension of the colonial project, co-opting and commodifying cultures to serve the white gaze, Patrick visits local communities to uplift those who forsake the trappings of modernism in favour of authenticity. After completing these projects, Patrick put the camera down. Rather than compromise his vision and produce work for mere wealth, status, or clout, he understands that what matters most is quality over quantity.

“I have to feel it deep within myself to be motivated enough to take pictures,” Patrick says. “I’m not a journalist. I make portraits, and why I am drawn to one person more than the next is extremely complex to explain. I gave it all I had in order to make a great photograph. The four subjects in the book came as a vision, and I became obsessed. That’s all I wanted to do. That’s it.”

Credits

All images © Patrick Cariou