Pedro Almodóvar refers to his films as offspring, explaining his current stay in London to akin to child care arrangements. “I have to take care of my baby,” he says of promotional duties for Julieta, his new film. It is also his 20th in a career spanning four decades.

It’s the filmmaker himself, now 66, who made a splash in the 80s as the enfant terrible of Spanish cinema, turning all that was dour and grey in arthouse films at the time into a giddy, flamboyant, and melodramatic cry of liberation. Now regarded as a spiky figurehead of the Movida Madrileña — the counter cultural scene that sprung up in the wake of 40 years of fascism under Franco — Almodóvar made freedom to do anything his calling card. He put the marginalized, from trans people to drug dealers, centers stage. He stole tropes and loopy narrative turns from the telenovelas and gossip magazines of Spanish housewives. He put women at the very heart of the drama and made icons of actresses like Carmen Maura, Rossy De Palma, and later, Penelope Cruz. The early results were riotous: nuns on acid in Dark Habits, a sympathetic psychopath in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, the trans sister-in-affair-with-her-father plot twist of Law of Desire.

As Almodóvar matured, so did the films. International acclaim, Oscar nominations and offers to direct in Hollywood followed his masterpieces All About My Mother, Talk to Her, and perhaps his most autobiographical film, Bad Education. He has never gone transatlantic though the temptation has remained. Even Julieta was initially planned as a his first in English. As it turned out, Julieta was filmed at home in the filmmaker’s beloved Madrid. It shares the DNA of Almodrama (as Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante referred to the oeuvre) in its impeccable consideration of space and architecture (Almodóvar films tend to work well as home décor mood boards); it spells a return to women at the forefront of its story too.

But it is also represents a late career step change. A story of a woman whose teenage daughter abandons her without any notice, it is a study in grief and loss. No comedy, no breakout singalongs, no flamboyance. Even one of Almodóvar’s muses, Rossy de Palma, plays her part entirely straight. In a brief sit down with the director in London, we start with asking him about that new found, late blossoming restraint.

Why did you decide to restrict yourself with Julieta?

There were temptations to put comedy in. Especially with the character played by Rossy de Palma. There are many comic possibilities in her sequences. During the rehearsal, I wouldn’t put the breaks on so you could have that comic version in the rehearsal and then you’d remove it so the actresses experienced that other way of doing it. I deliberately erased that comedic element from the shoot.

Was it difficult to restrain yourself in this way?

I have a very baroque spirit. I adore melodrama but I felt the very best way of doing the story was through a somber and restrained tone. This was a new possibility for me; I welcomed and embraced it. I’m extremely happy to have taken this direction. I’m pleased not to have opted for the baroque dimension so there’s no singing in the film, there’s none of that opulence.

That restraint plays out in different ways. For a film about grief, there is very little crying in Julieta.

It’s a film very close to pain but I didn’t want to see them crying. I wanted the pain to be there on the looks on their faces. But the moments of crying are in the scenes we don’t see. When we see the older Julieta, we see the pain in her face. She’s lived with that pain so there’s no cries, no sobs. When the young Julieta identifies a body, I told the actress Adriana Ugarte if you need to cry, then cry but try to fight against that because that fight is very cinematic. The camera doesn’t like [Almodóvar pulls a huge crying face]. It’s ugly.

There is a tremendous sex scene on a moving train, set in the 80s. You’ve spoken previously about how a young woman wouldn’t experience liberation like that now. Can you elaborate?

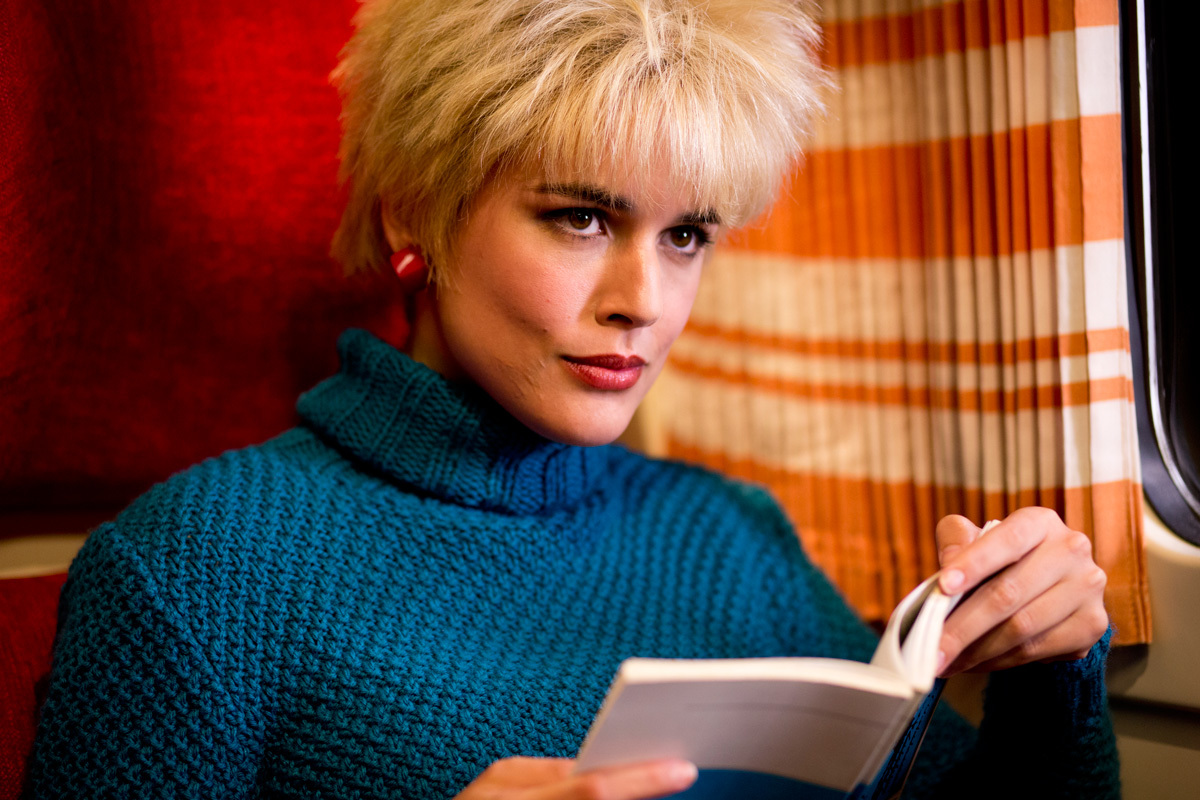

The mentality is quite different now. A young woman who finds a man on the train and has sex with him would probably be classified as a loose woman, an adventurer in the worse sense. But in the 80s this was part of women’s lib, it was part of liberation, of freedom in that decade. You have to remember that the 80s was about a new democracy in Spain after 40 years of dictatorship. After 40 years there is a great sense of liberty for men and women. For Julieta, she’s about the pleasures of the body, she’s got that hair [a peroxide blonde, spiked haircut not dissimilar to Almodóvar’s own], that outfit. But she’s also a schoolteacher. I knew women like that in the 1980s. This film has a very Madrid, 1980s context. Now the character would be very different. She’d have a more bourgeois life; she’d express her liberty in a very different way. But we live in a very different society now.

An early reading of your work called it ‘the opposite of restrained good taste.’ Julieta is in extremely good taste.

When Dark Habits opened it was described as “often tasteless but never dull.” And I loved that.

What would the younger Almodóvar make of such good taste?

It’s a different taste. But then I saw myself at that time as having good taste. I come from the underground at the end of the 1970s and that trash culture left a mark on my work. It’s the culture I absorbed in my youth. But also Ingmar Bergman infused me so on the one side there’s John Waters and Andy Warhol and on the other [Michelangelo] Antonioni and Bergman. Different canons. A sense of balance. The aesthetic of the 1980s now looks very aggressive to us but I’m of that time. My first movies were very underground. They seem like a formal mess but now I’ve moved towards something which is much more stilled and contained and I like the two extremes.

What film would you recommend a younger audience coming fresh to your work to begin with?

Start with Law of Desire. I’m very satisfied with that film. It was the first film with myself and my brother [Agustin] as producers. Desire — physical desire — is the protagonist of the film. The theme is in many of my films. It’s a very vital in life and vital for young people, who are confronting and engaging with their own desires.

Julieta is in cinemas from August 26. An Almodóvar retrospective continues at the BFI, London through September bfi.org.uk

Credits

Text Colin Crummy