Author Linda Rosenkrantz has long been a believer in the power of conversation: a means of revealing those rich intersections between truth and fiction, life and art. For her now-acclaimed literary experiment Talk (1968), she taped the cool, hilarious and clinically frank chit-chats (and psychobabble) between three art world New Yorkers and transcribed them verbatim.

Linda’s new book, Peter Hujar’s Day, published by Magic Hour Press, follows in a similar vein. In 1974, she asked various friends to note down everything they did on an arbitrarily-chosen day and pour it into her tape recorder. One of those friends was Peter Hujar, who liked the idea, despite the supposed mundanity of his chosen day: December 18 1974. “I think, well, I didn’t do anything,” he confessed to Linda. “I just photographed Ginsberg, and that woman from Elle.” What begins as a banal recollection of an unremarkable day unfurls as not only a fleeting resurrection of Peter’s social network — the scrappy stock of the downtown demimonde of the 70s — but a poignant, unvarnished expression of the way he saw the world, through the lens and outside it. Here, Linda opens up about that conversation and their five-decade-long friendship.

How did you and Peter first meet?

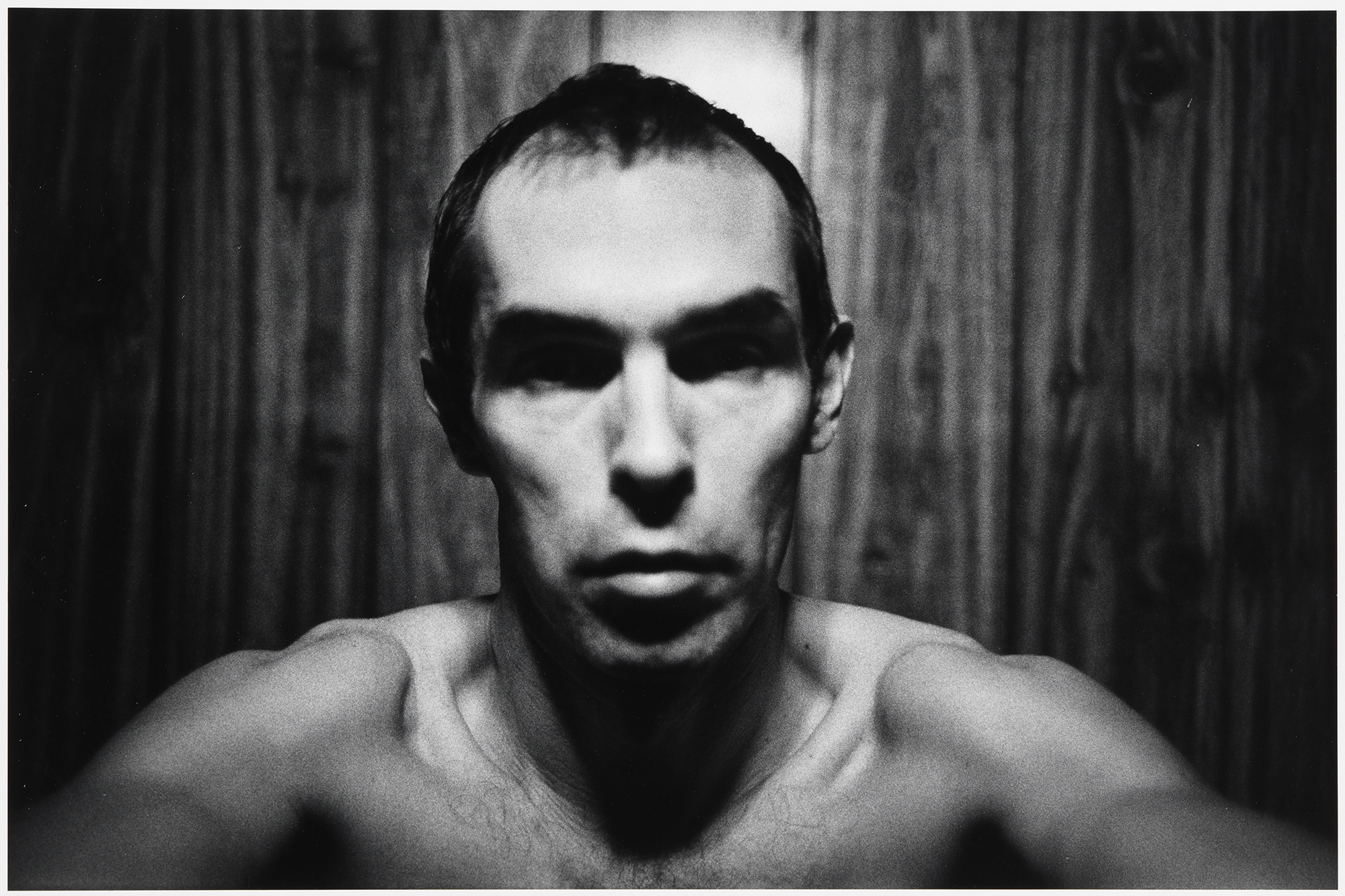

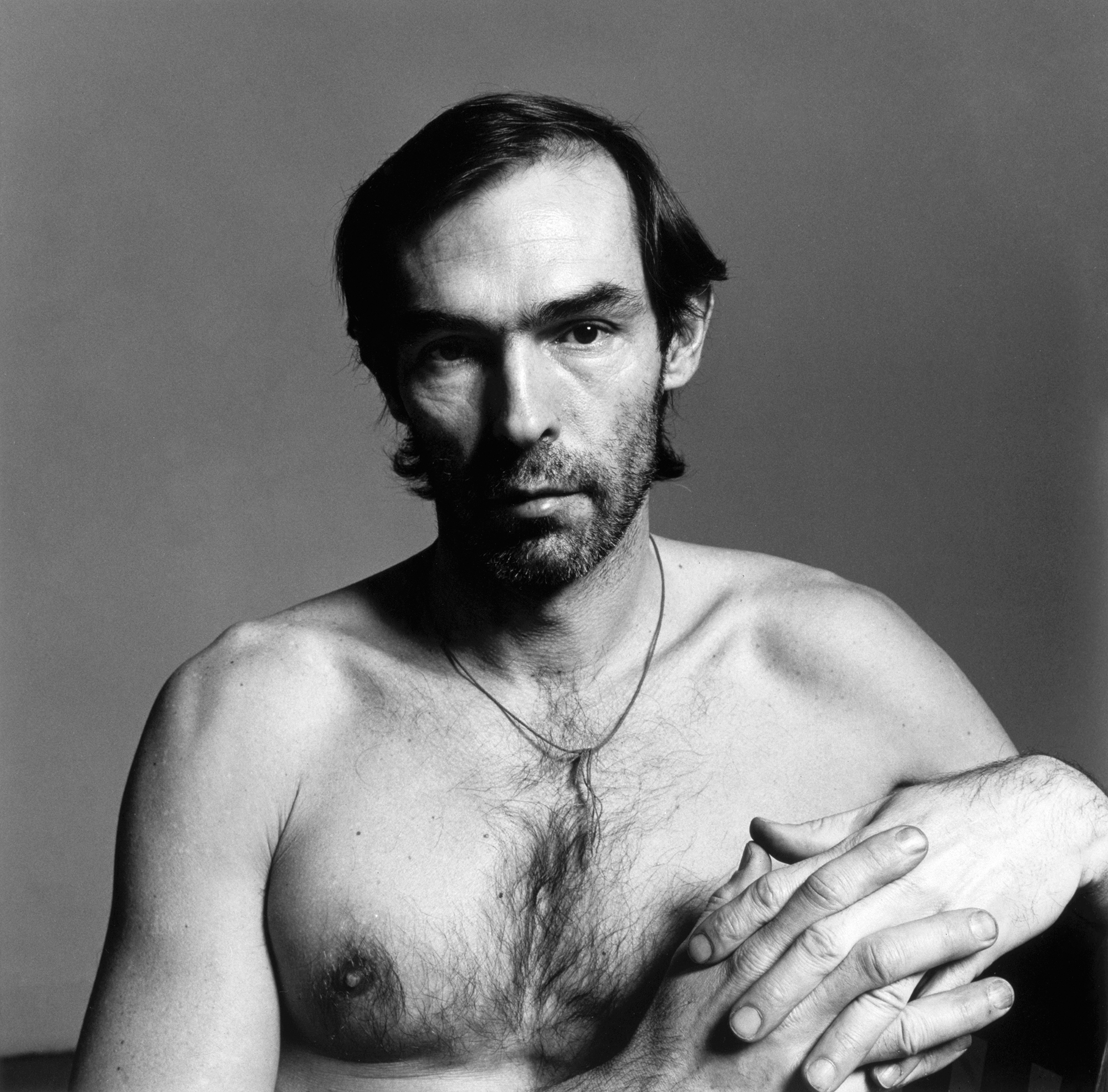

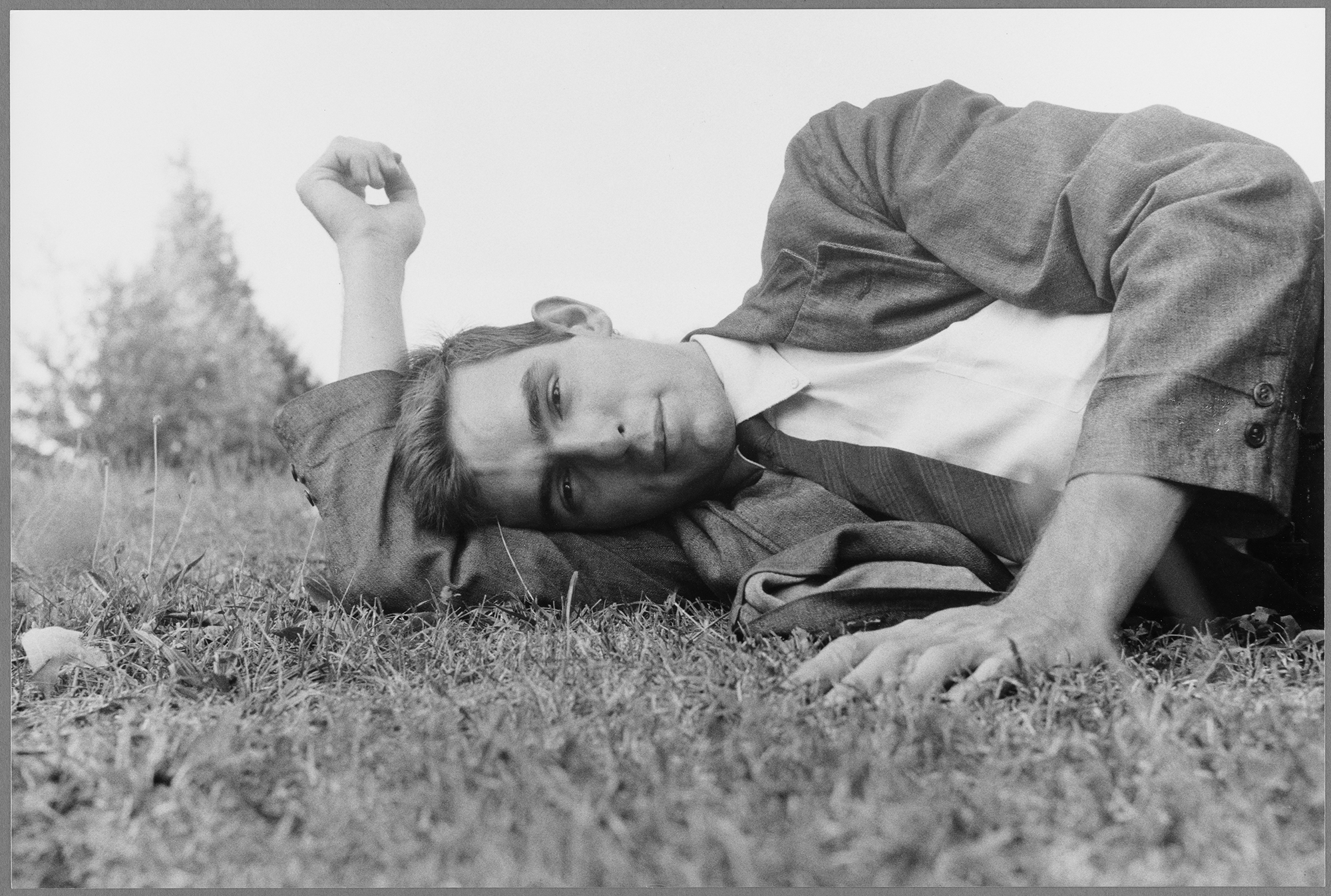

I met Peter in 1956 when we were both in our early 20s. This was soon after he had moved in with the painter Joseph Raffael (known at the time as “Joe Raffaele”), who was then my closest friend and confidante, and it wasn’t long before we became something of a triad. I found Peter intriguing — tall and handsome, shy and sly, looking at the world from out of the corner of his eye; already solidly committed to photography.

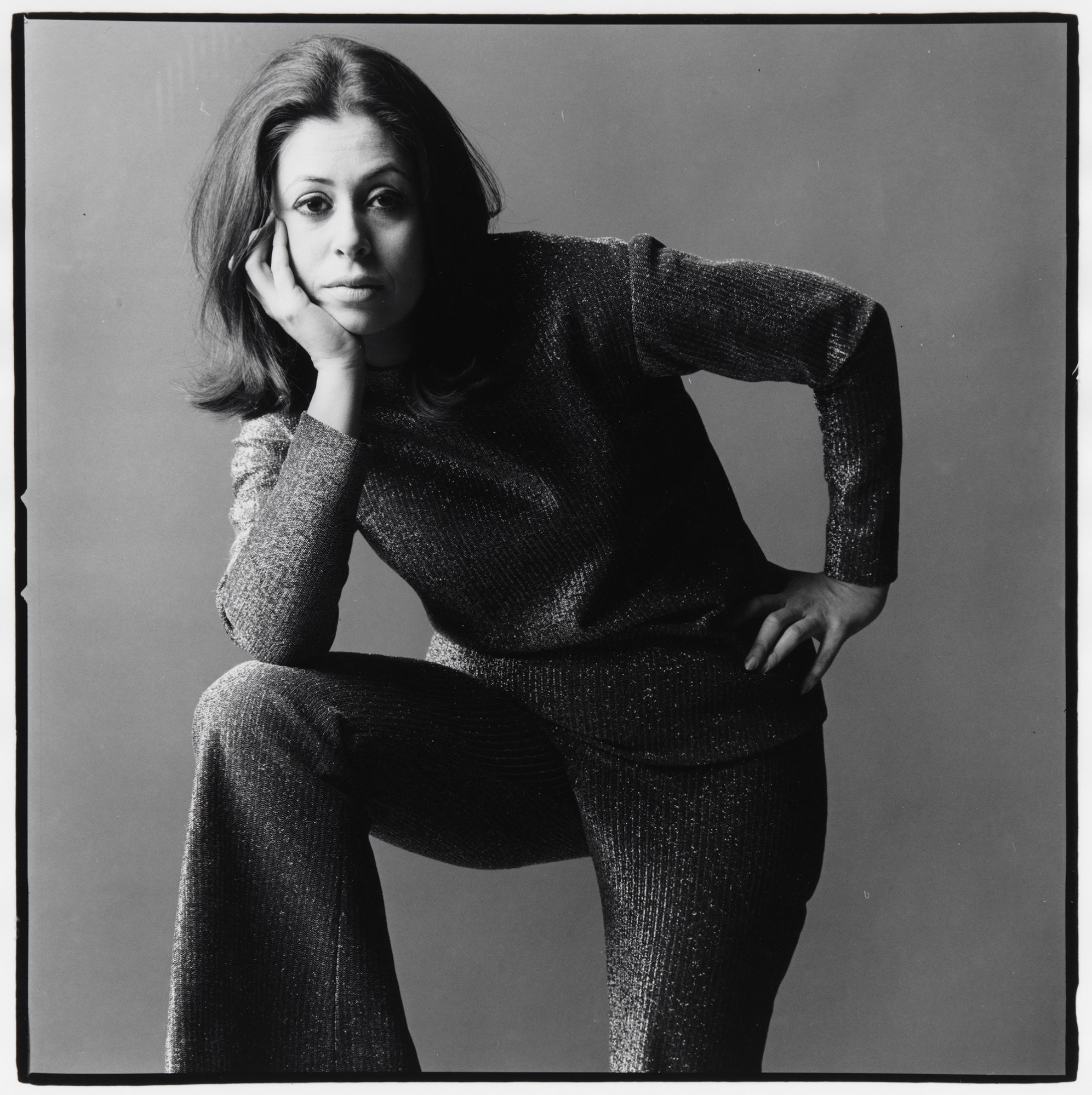

Joe and Peter lived in a wonderful plant- and music-filled apartment on the Upper West Side of New York, along with a fat grey cat called Alice B. Toklas, and this became my almost nightly after-work refuge. It was there that Peter photographed me for one of the first times in a relaxed shoot with my much younger sister. Another very early occasion was when Peter, Joe and I took the subway to Times Square expressly as a Hujar photographing excursion, and he shot the very young-looking me in a Photomaton. I was amazed to be told recently that there are probably over a thousand separate shots of me in his archive.

This was a time in my life when, recently graduated from college, I was working at my first (and, it would turn out, last) full-time job, in the editorial/publicity department of Parke-Bernet Galleries — an auction house that would later be swallowed up by Sotheby’s. Together and separately, the three of us were all just dipping our toes into the New York art world that was beginning to explode.

Do you have any memories of those first occasions that you found yourself in front of Peter’s lens?

The first few times were very casual and not formal sittings at all, so it wasn’t that different from having my picture taken by anyone else. Strangely enough, I’m having a hard time recapturing the experience of the later photoshoots — of what they felt like. But there are enough examples of me laughing or goofing off to tell me that it wasn’t always super serious.

When did the trip to Italy happen?

That was two years later, when Joe had gotten a Fulbright grant to paint in Italy. He and Peter were living in the ancient stone Villino Fioravanti in Bellosguardo, on the hills overlooking Florence, and they invited me to come for an open-ended stay. Being there with them proved to be one of the most magical times of my life. Actually living there together, my bond with Peter was at its strongest. During the day, our lives were almost monastic, with Joe painting in one room, me struggling over pretentious short stories on my Olivetti in another, while Peter might be studying Italian or out in the garden tending to his zucchini and zinnias. After dinner, we would get together in one of the common rooms, speculating about what our futures might be. A lot of the conversation consisted of them encouraging me to find a Virginia Woolf-esque room of my own and to be bolder when I returned to New York.

I understand that it was upon your return from Italy that you met Peter’s mother, and you were, as far as you know, Peter’s only friend to have met his mother…

Yes, I don’t know of anyone else who spent time with Rose Murphy (almost always referred to by her full married name, though sometimes as “Rosie”). Peter didn’t talk to me much about his childhood, which, in retrospect, is kind of strange in light of the abusive portrayal of it — and her — that has emerged since his death. But Peter was a master of compartmentalisation, consciously and carefully separating the different periods and elements of his life. I did know that he had conflicted feelings about his mother, but he was fairly light-hearted when he spoke about her.

After I returned from Italy, he asked if I would deliver a gift to her (Florentine gloves?) and so I subwayed up to the far reaches of The Bronx where she and her husband (known to all as “Snookie”) lived. I was greeted warmly, certainly not by the homophobia I had anticipated. They quite comfortably referred to Peter and Joe as “the boys” and even expressed the hope that they might find an apartment in their neighbourhood when they returned. A couple of times after that, Rose Murphy met me at my Madison Avenue office for lunch, smartly dressed in hat and gloves.

I’m interested to hear about what inspired you to record conversations — from those between your three friends in Talk, to yours with Peter in your latest book. Had you always intended to publish them?

With Talk, the idea came to me in a flash as I was about to leave for my summer rental in the Hamptons. My thought was to take a tape recorder, keep it running, Warhol style, and see if it might make a book. It soon became obvious that having a cacophony of voices just wouldn’t work and so in the transcribing and editing — which took about a year — I pared it down to just the three voices in the book.

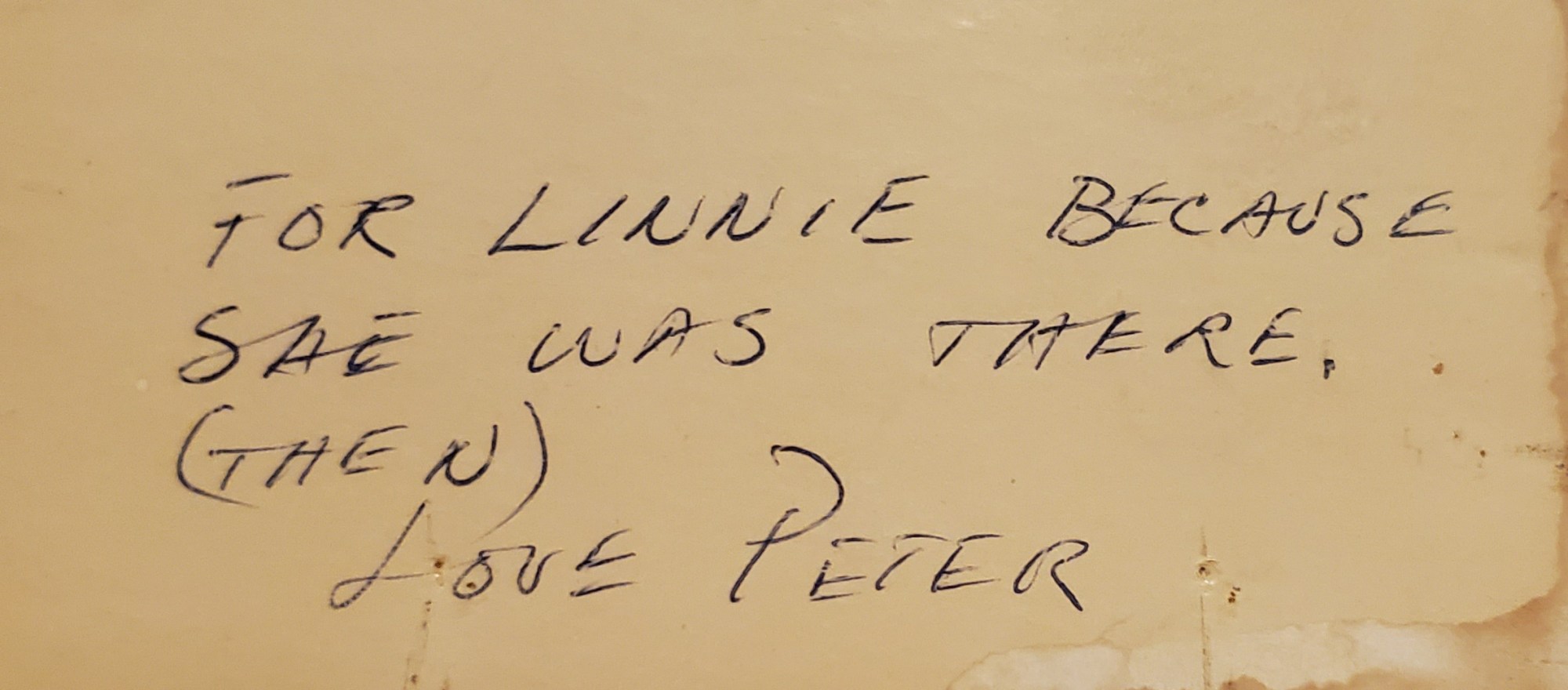

The Hujar book was part of a larger project that was very much conceived of as a prospective book. I asked a number of people to pick one day in their lives, take notes of everything they did that day and then meet with me to record their report. The first two I did were with Peter and Chuck Close — who happened to be in the process of painting my portrait that day. The Hujar “day” was never intended to be a book on its own, and its backstory involves a lot of serendipity. Art historian Marcelo Gabriel Yanez came upon the transcript in the Hujar archive at the Morgan Library and told Magic Hour’s Jordan Weitzman about it. Jordan in turn mentioned it to Francis Schichtel, who was working at the Hujar estate, and they had the idea that it could be a book and went on to produce it so elegantly. It was a very collaborative effort that also included Stephen Koch, who wrote the introduction.

How did the recording process work?

I left it up to Peter to pick the day, and, fortunately, it was one that happened to include interactions with, among others, Allen Ginsberg, Susan Sontag and Fran Lebowitz. He came up to my apartment on East 94th Street… I probably would have made dinner for him. Then, at some point, I turned on the tape recorder, and he relayed the events of that day. I’m not sure if I was using the big, bulky machine I had used for Talk or a more updated, portable one.

Mid-way into the transcript, you learn that Peter had actually forgotten your request to note down the events of his chosen day before the sitting. The extreme precision of his memory is all the more impressive with this in mind. In the introduction, Stephen writes how Peter remembers things visually, or even, photographically.

Yes, “distinctive” is the operative word. Stephen and I were just talking about this recently: how both of us can still hear Peter’s voice so clearly after all this time, and yet it’s difficult to describe it in words. It was quite deep and sonorous, yet understated; at times, it could be conspiratorial, affectionate, gossipy, informative but never pedantic. As he wrote in a letter to me once: “You know how I love details”, and that was the charm and fascination of his speech; how richly textured it was. Of all the Day in the Life tapings I made, his was the only one that was truly a conversation that reflected the intimacy of our relationship; the others were almost strictly reportage – “I did this, and then I did that…”

There are a few things I can actually hear in his voice. Like him telling me once that he had two pieces of advice for me:

- Never say “No” to your daughter and…

- Wear more jewellery.

One of the great virtues of the monologue is how it is “about” Peter yet without any self-indulgence. And although intellectuals, luminaries and other downtown peers pass through his chat, they are never name-dropped. How did you interact with Peter’s various circles?

There was very little overlap. Of course, in the early years, there were mutual friends like Joe Raffaele and Paul Thek and later Vince Aletti. Oh, and I did get to know some of his boyfriends. Steve Lawrence became a friend, and there was a surreal evening when he brought over Jim Fouratt and his dogs. But, for example, I have never met Fran Lebowitz or Nan Goldin. One exception was Susan Sontag. She and Peter and I were part of a small group that went dancing — these were the days of the Frug, the Hully Gully and the Mashed Potato — at a place in the Lower East Side called The Dom, and the same group also went ice skating in Central Park a few times, always on Friday nights. There was one almost-connection, and that was the rock critic Lisa Robinson. Peter said several times that he wanted to introduce us because he thought we could be friends. Never happened.

Going back to Peter’s tendency to “compartmentalise”, would it be accurate to say you represented, for him, a more domestic side?

I do think that when I got married and especially once there was a child, he found a kind of serenity in our place in the way-West Village, maybe seeing us as just this side of bourgeois (saved by our creative pursuits). I remember one night, he came over and was cheerfully cutting out paper Christmas tree decorations with my daughter Chloe when, at a certain point, he announced that he was leaving to go cruising at the nearby piers.

Included in the book are two photographs of Peter’s loft at 189 2nd Avenue. How do they correspond to your memories of the place?

To me, those two photographs look like a glamorised version of the loft in my memory. I saw it as very minimal. For instance, I know that he had a harpsichord, but was there ever really a piano? One strange thing is that several of us survivors have different memories of both the size and the placement of Peter’s bed.

It’s quite difficult to reconcile the grandeur of those two photographs with what was in reality a penniless existence…

Indeed, and very much in contrast to his rich creative and social life. Tuna casseroles were his standard dinner fare, he had a very limited wardrobe (which he was fastidious about maintaining) and coming up with the rent money was always a challenge. When anyone went out to dinner with Peter, it was always assumed they would foot the bill, and I remember one time, when we were switching our sheets, we gave Peter the replaced ones, which he was really excited about. Things like new sheets and towels were not in his budget. There were gifts of clothes too. I recall the requested (quite expensive) Pendleton flannel shirt, and the dark blue Guernsey fishermen’s sweater we brought back for him from my husband’s native island, which can be seen in many pictures of him and which he loved so much that he once said he’d like to be buried in it.

Do you think Peter ever had a hunch that his prints would sell for such huge prices?

I think Peter knew how good he was, and although his stubborn principles and demands did sometimes get in the way of commercial success while he was alive, he foresaw recognition. He once said to me very early on: “I’m going to have a show at the Museum of Modern Art next year.”

I think he’d be especially pleased by how favourably he’s now being compared to Robert Mapplethorpe, as more and more viewers appreciate the unparalleled depth, mastery and humanity in a Peter Hujar print.

Peter Hujar’s Day by Linda Rosenkrantz is published by Magic Hour Press