London, 1955, and Daniel Day-Lewis is Reynolds Woodcock, dressmaker to dames, royalty, movie stars. Frustrated at work, he takes a break to the country where he meets Alma (Vicky Krieps), an immigrant from eastern Europe who enters his life and joins him at his home and atelier, the House of Woodcock. There she’s forced to share Woodcock with his elder sister Cyril, the matron of the house, played with fantastic Mrs. Danvers sternness by Lesley Manville.

First things first, Phantom Thread is a brilliant film. Suspenseful, funny, exquisite, exquisitely acted. There’s a sort of old, masterful quality to Paul Thomas Anderson’s direction; a big, gothic romance that plays out, largely, in the menacing, Hitchcockian serenity of the home.

So far, much attention has focused, understandably, on Day-Lewis. The Anglo-Irish actor has already announced the film is to be his last, the ending to a glittering career gilded with a record three Academy Awards for Best Actor, first for his portrayal of Christy Brown in 1989’s My Left Foot, then for There Will Be Blood and Lincoln in 2007 and 2012 (he’s nominated again, for this, at next month’s ceremony).

Here, Day-Lewis plays Woodcock with the same endlessly watchable intensity he brings to all roles. He’s arrogant, dangerous and unmerciful as a designer obsessed with perfection (“You have no breasts,” he remarks coldly to Alma, during an impromptu dress fitting on their first date). But he’s also powerfully charismatic; romantic and playful too.

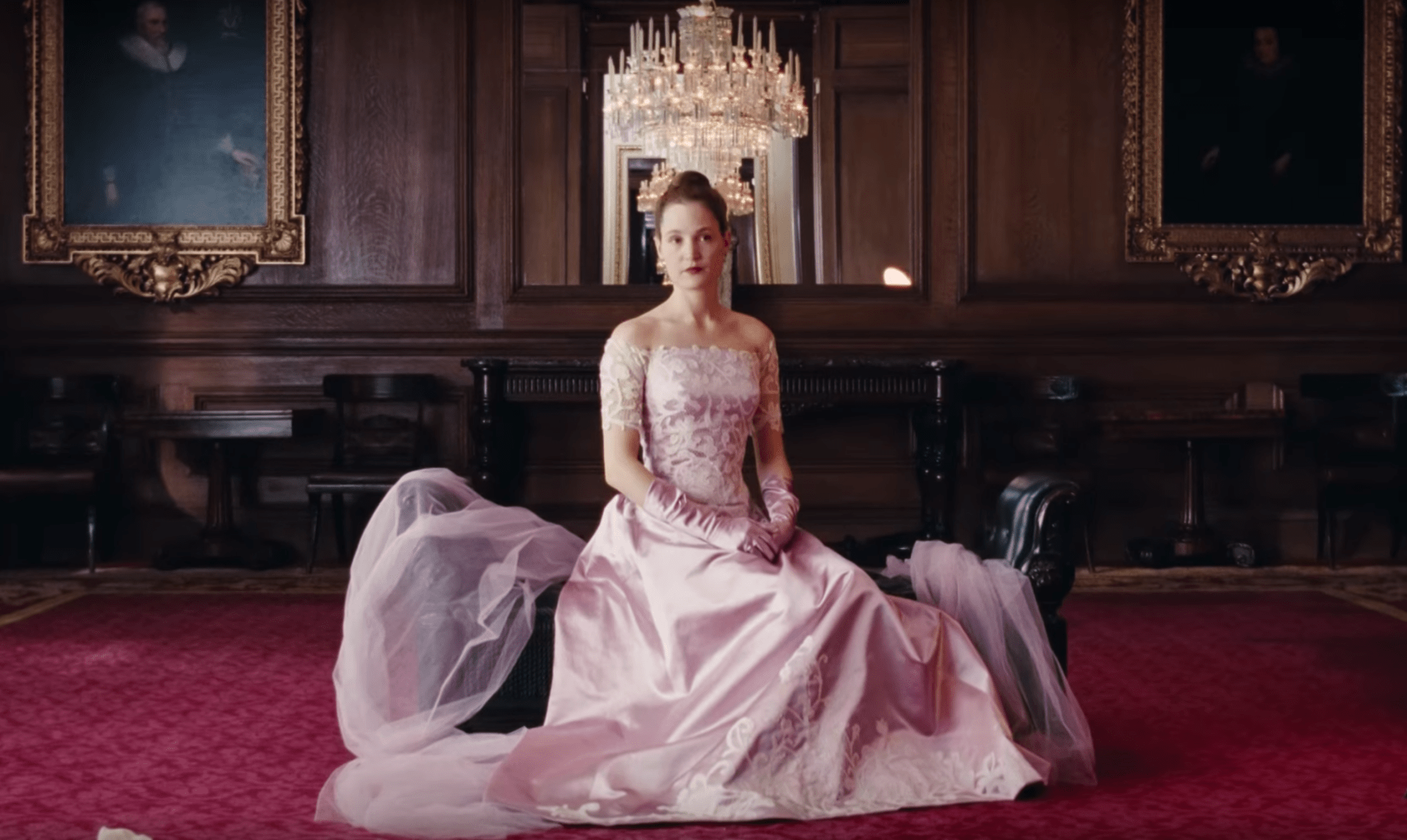

They first meet in a seaside cafe at which Alma is a waitress. Flustered and mousy, she appears sweet, but in comparison to the Beau Brummell-esque Woodcock, dowdy and a little socially awkward. When Woodcock offers to rescue her from her modest life, inviting her to live with him in London, it’s clear which way the story is headed: Alma is to play the live-in companion and muse, existing in submissive obligation to her more powerful partner.

And that’s where Phantom Thread gets interesting. While much discussion of the film has focused largely on the idea of the tortured male genius (even its poster sees the head of Day-Lewis loom large, with a diminutive Krieps positioned neatly within), it is the character of Alma that gives Phantom Thread its dancing, chesslike melodrama.

Less a straight romance and more a study of power within a relationship, it slowly becomes apparent that where we’d expect to see a male artist abusing and admonishing his female counterpart (and for a good portion of the film, that’s exactly what he does), Anderson delivers in Alma a character that can more than hold her own. “If you want to have a staring contest with me,” she warns Woodcock early on, “you will lose.”

What’s more, while Woodcock begins to doubt his affection for Alma — infantilising her or measuring her against the memory of his dead mother (do another shot in your attachment disorder drinking game) — she grows only in stature in the eyes of Cyril, the previously icy guardian tasked, at the start of the film, with removing tired and spent muses from the home.

Just as one expects the two women to be set in direct competition, they begin to find a mutual understanding. An agreement that, alongside the countless seamstresses that ensure the atelier’s smooth running, suggests a kind of respectful unity between the film’s women. By the end it’s clear — as strange and complex as their relationship may be, Phantom Thread is Alma’s story to sew, not Woodcock’s.

Phantom Thread is out now.