Philip Montgomery was one of the few people to attend both 2016 presidential candidates’ ‘victory’ parties in Manhattan. On assignment for The New Yorker, the California-born photographer had accreditation to both events, and as Donald Trump’s success became clear in the early hours of 9 November, he took a taxi from the Javits Centre in Hell’s Kitchen (whose imposing glass ceiling Hillary Clinton was to metaphorically ‘smash’ in victory), to the Republican event at the New York Hilton, a few blocks south of Central Park. While most of the country’s liberal media crowded the Clinton camp, Philip describes Trump’s spectacle as a “drunken, tailgate-party” with just a handful of media present. A bust-like cake of Trump’s head attracted the attention of photographers in the hotel’s ballroom, each eager for their slice of history.

“I had no doubt in my mind as to who was going to win,” Philip says. Photographing around the US in the two years prior to the vote (and since) convinced him of Trump’s ascendancy, especially in the rust belt and Southern states. He recounts his prescience with a tone of powerlessness rather than self-satisfaction; on a night where the impotence of the media class to which he belongs was brutally exposed, there is little room for complacency. “I think we were all guilty of overlooking what was happening,” he tells me. The memory seems tinged with pity, not just for himself or his craft but also for his country.

American Mirror is Philip’s response to the events of the past seven years, a photobook of 71 plates telling the story of a fractured nation. A mixture of personal projects, commissions and assigned work (mainly for The New York Times Magazine and The New Yorker), the book crosses states lines and demographics, documenting the opioid epidemic, evictions, floods, wildfires, racial justice protests, the 6 January riot on the Capitol, and the first 18 months of the Covid-19 pandemic. The work started in 2014 in Ferguson, Missouri, with the death of Michael Brown, a key event in the early development of the Black Lives Matter movement and a new civil rights era. “His death was a moment unlike any in my generation’s understanding of America,” Philip says. “The country wasn’t well.”

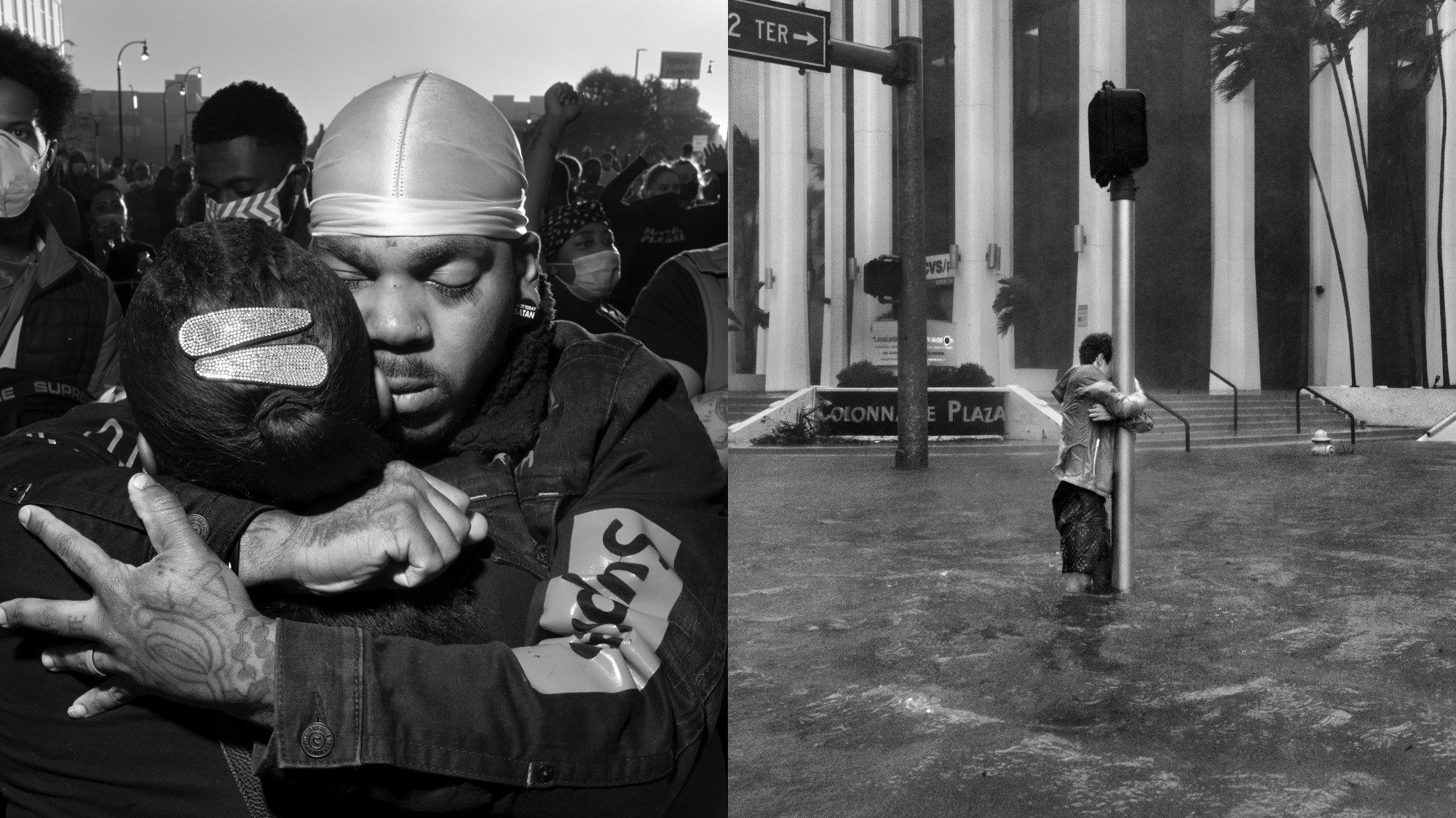

Philip’s style is piercing. Shooting in black-and-white, the photographs veer from motif-based, distanced commentaries to, at times, portraits of almost unbearable intensity. Several depict people on the brink of overdose; armoured police move through thick clouds of tear gas; on front lawns, filled body bags lie motionless as family grief writhes around them.

“These images seem like a series of exhibits of the sort presented to a jury,” writes Jelani Cobb in one of two accompanying essays. “Whether this is a case for our collective defense or our prosecution remains to be seen.” It is true that Philip curated the selection with one eye on posterity, but if American Mirror is gathered evidence, it is intentionally partisan. The images’ short descriptions condemn a wide range of institutional failings, from PPE shortages to a broken rental system. (In the second text, Patrick Radden Keefe describes the 21st century as “a perfect zero-sum game in which every debit in the lives of working-class Americans became just another credit for the plutocracy”). Philip wants to counter the nation’s dominant narrative, he says, “to build this case that America is defined as much by its fissures as it is its nostalgic fiction of greatness.”

This is not, then, strict photojournalism; Philip rightly points out that few of these images would work on newspaper front pages. From growing up in the Californian desert, his move to New York City (and then travelling inland to work) led him towards the American magazine tradition made famous by Life. Profound, complex human storytelling enlarged on glossy pages, to be pored over at weekends and, if they serve their purpose, filed away as historical bookmarks by readers. Narratives emerge over thousands of shots rather than a single moment of impact.

What is the effect of condensing these series into a photobook? American Mirror‘s coherence relies on the interconnectedness of America’s social ills, Philip says. “If you’re working on a story around an eviction, you’re probably going to be looking and finding yourself touching on a number of other issues that are central to the American experience.” That could mean the lives of undocumented workers, unofficially segregated housing, the ravages of addiction, or the economic fallout of Covid-19. Sometimes these overlaps embroil the country’s figureheads, too. “Late Rent” shows an eviction notice stuffed into a door knocker for an awaiting tenant. The photograph was taken in Baltimore County, Maryland, where a corporate property owner (subject to more than 200 code violations in 2017) persists with evictions of low-income families. The part-owner of the company in question? Jared Kushner.

“I want the viewer to feel the heavy hand of authorship in each picture,” Philip explains. The images can be imperfectly categorised into three types, allowing the selection to zoom in and out of this entwined American condition — honouring character while maintaining anthropological scope. First there are American Mirror‘s high drama social scenes; cinematic in the plurality of emotions they capture. “Saying Goodbye to Brian” feels like a specially designed anti-drug scare poster. Police and family surround the body, each caught in a moment of private but painfully public mourning. “The People’s Way” shows the Minneapolis intersection where George Floyd was murdered, bustling with organisers in June 2020. On the roof of the adjacent gas station, the silhouettes of six people look upon the crowds while a man examines an American flag below. The photographer goes unnoticed and, although on the boundary of encroachment, is relatively uninvolved in driving the narrative. Tragedy tells its own story.

Then there are the single-subject studies, where traditional portraits emphasise either standalone influence (in photographs of Trump, Clinton, Jeff Sessions and Tucker Carlson), or desperate loneliness. An incarcerated woman looks dejected as she phones home from the ‘detox’ wing of Montgomery County Jail in Ohio; one man clings to a lamppost as floodwaters rise around him in Miami; another collapses after first responders save him from a heroin overdose. Here, subjects are unaware of all they embody, that their private struggles are symptoms of a national sickness. For all of these afflictions — addiction, infection, incarceration, mental illness — aloneness is a key facet of their stranglehold on the weakening individual. It’s curious that often in American Mirror, it is only in death that family and the authorities reconvene around a subject. Too late to care; in time for grief.

The third style is shots of objects or scenes where people’s identities are obscured, and anonymity and motif combine. Hands raised aloft in the “don’t shoot” pose, a burnt-out car during California’s deadly 2018 wildfires. In the eviction-themed shots especially, the absence of subjects contributes to a sense of inhumanity — of both life and livelihood as transaction and deadline. These are where we notice the street photographer’s hallmark: the act of seizing upon the mundane and elevating it, imbuing it with historical importance by bearing witness when others choose not to.

Perhaps American Mirror signals a new form of street photography. “Americans have, at this juncture in our history, become accustomed to conducting our most painful reckonings in public,” Cobb writes. This is certainly true for the Black Lives Matter protests, as it is for the country’s empowered right-wing response. But where to situate what American conservatives have traditionally considered private or personal struggles? Addiction, illness, inequality. The great American delusion is that these experiences do not define the fabric of everyday life; that they are the concern and fault of a minority of individuals. But American Mirror forces its material into relevance. By insisting that the country’s fractures are as momentous as its glories, the book inaugurates a new way of seeing: a visual confrontation, aberration even, to a national fiction that fewer and fewer believe in.

‘Philip Montgomery: American Mirror’ is available to purchase here.

Credits

All images courtesy Philip Montgomery and Apeture