The first time Jack Pierson left the Northeast, he got stranded in Florida for six months.

Let’s backtrack: Pierson is an artist perhaps best known for his “word pieces” — poetic sculptures assembled from old signage. His multidisciplinary practice spans photography, painting, drawing, installation, and video work. He’s a Massachusetts native and is associated with the Boston School, a group of artists and photographers that includes Nan Goldin, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, and the late Mark Morrisroe and David Armstrong. It’s an influential collective, but an informal one. Its “members” met in Boston, where they studied at art colleges in the 1970s. By the early 80s, many of them had decamped to New York.

Pierson arrived in the city in 1983, when he was 23. “When I got to New York, I was the same age as Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, who had already been flying [on] the Concorde with Grace Jones for five years. So, especially in the first six months, it sort of seemed like: ‘I’m too late, I’m washed up at 23.’ They were already doing it, and I was still really figuring it out,” he remembers.

So, on a whim, he took a trip to Miami that Christmas. “I thought I’d stay for a week,” he laughs, “but I was too broke to get back.” Without a credit card, Pierson had to get a job in the Sunshine State. It took him six months to earn the money to make it home. “It was fun, though! It was my first time escaping the Northeast. And I think that experience sort of made me something else. I began to think more expansively.”

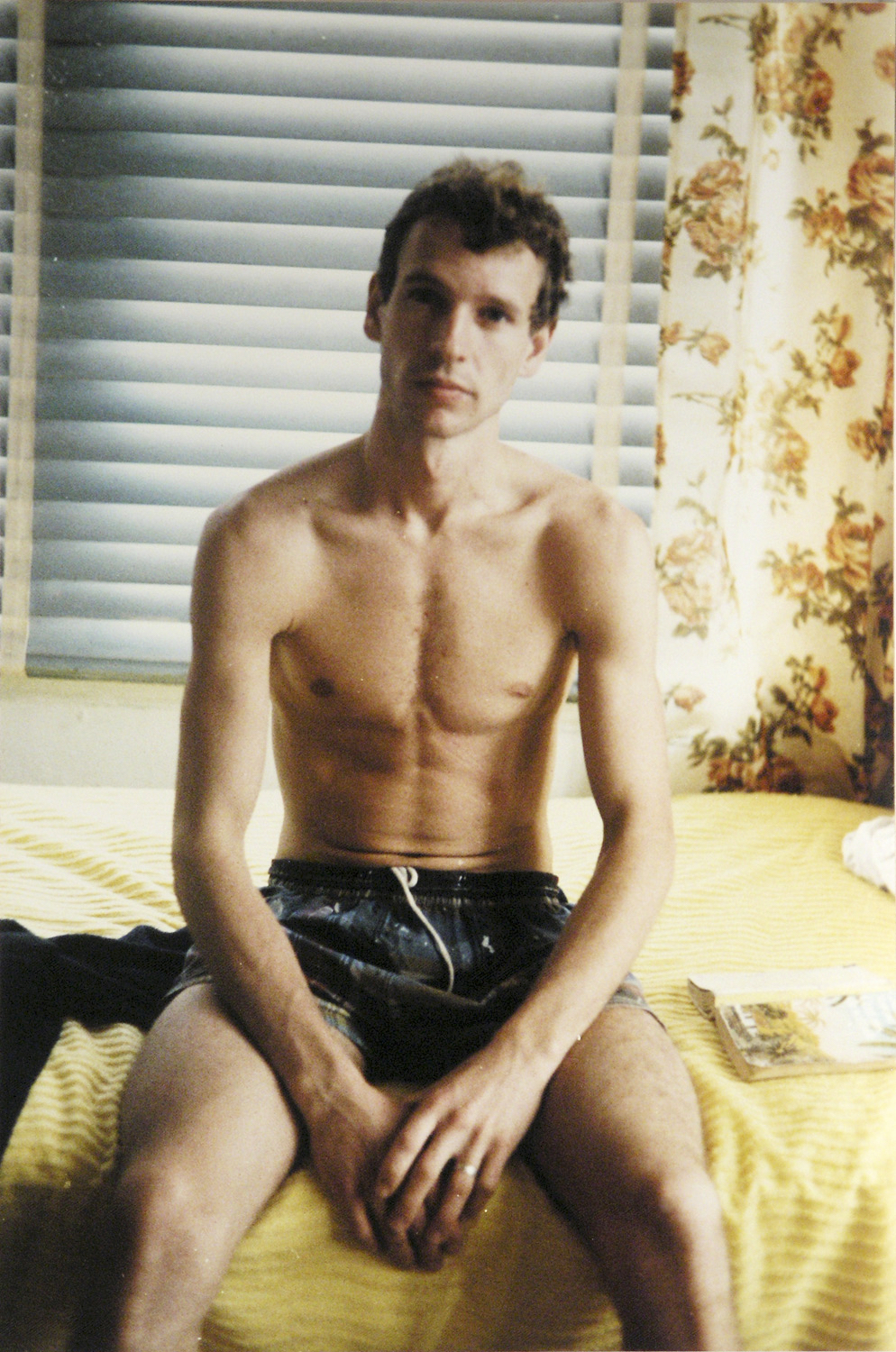

Pierson’s Miami photographs appear in his excellent new book, The Hungry Years. The work’s sun-faded snaps were made throughout the 1980s, during the artist’s trips to El Paso and Palm Springs, Miami, Baltimore, Boston, and the Badlands. There are pictures of hotel rooms, bedmates, and beaches, as well as friends’ homes and pets. Times Square in the rain, Janis Joplin’s apartment complex. Portraits made at dusk and dawn.

The book is an honest and tender testament to what its name suggests — those years of struggle, of striving to make a life as a creative person. Ahead of the book’s release, Pierson tells us more about his hungry years.

What I like about these photographs is that they feel so personal, but also cinematic and humorous in an American way. Has your view of them changed over time?

I’d been to art school, and I knew photography had the possibility of being art. But I was taking pictures of my life; I wasn’t thinking of the pictures as art. Until 89, when I went to L.A. That’s when the pictures started to make sense together.

Tell me about when you did begin to see them as artworks.

I was living in the Village, and there was a little photo shop. They offered a service where they’d blow your pictures up to a 20 x 30 poster, for $10 a poster. I was curious, so I brought three photographs to be made into posters. All of them came back super funky. Much more than I even imagined. They had this dusty, grainy, weird, out-of-focus quality to them. I thought they looked pretty cool.

Around that time, I got my first credit card, which had a $500 limit. I went through all my negatives, picked out 50, and blew the whole first credit on making them all at the same time. They came back, and I knew there was something to them. They were just big enough to command your attention, and they all had this quality of “art” — to me. In the first reviews I got, people were convinced they were found photographs. I thought that was a compliment! So natural they could have been found. In fact, there was a design to have them look like that.

What kind of camera did you shoot these pictures with?

Initially, I had the best camera I could have as an art student, a quality 35mm camera. So some of them were done with that. But when I got to L.A. for the first time, I hadn’t brought my camera. I was broke, and I didn’t rent a car. I walked every place. So I started buying $5 cardboard cameras, and I shot a lot with them. There’s a real range between high and low grade cameras. I think that’s also part of what gave the pictures this found quality. I stress the economics, because I think that played into the early stuff so much.

You mention living in the Village. You also had a studio in Times Square at that point, right?

I got that studio after I’d made it back from Miami, in 84 or 85. That was the next period in my life that was important as to what I’d develop into. There was a building in Times Square where every artist had a studio. The studios were in an office building, which closed at seven at night. And you had to leave, you didn’t have a key. Some people would let themselves be locked in so they could work overnight. I was never one of those people. But that’s what made it so cheap: it was only open from 7am to 7pm.

You started making word pieces in 1990. Do you feel that evolved from your pictures in any way?

I can tell you exactly what happened. In that studio, say from 85 to 89, I was trying to make paintings because it seemed like that’s what people wanted. I would have people over to look at them — the whole studio visit thing. Nobody was really biting, though. There was a guy who had a gallery on Lafayette Street. He’d been over a few times to look at my paintings. And when he came — say, in June of 90 — I also had a stack of those photographs.

He looked at the paintings, then he asked about the photos. So I started pinning them to the wall. Halfway through the 50, he said, “These are cool, let’s do a show. Are you willing?” I was like, “Yeah, absolutely!” So we did the show that September, sold a couple, and I paid off my credit card. It also did something to my ego. I was an artist. I had a show. I sold some work. There was a blurb in The Village Voice. I felt pretty good!

At that time also, in 1990, they were closing up Times Square. Weirdly, they were bringing a lot of the salvage stuff to tents on Houston Street, where they’d sell it in a flea market style. All of these marquee and sign letters started to show up. I went one day with my studio-mate at the time, being like two months behind on the rent. I pulled out these letters and started playing with them on the ground. I wrote a word. I asked the guy, “How much are these four letters?” He was like, “10 bucks each.” I thought it could be a cool artwork. My studio-mate was like, “You can’t spend $40 on those letters, are you kidding!” I was like, “Look, I know what I’m doing, I just had a show! I think I’m onto something.”

I brought the letters to the studio and put them on the wall. In fact, it did look like something. So I started having more people from the photo show over. One guy had come over five times and not been enthusiastic about anything. I showed him the word piece and he sold it like that day, I think for around $1,500.

That’s crazy! A $40 investment.

My failsafe for being an artist was that I could always be a flea market guy. It has everything I like: finding junk, reselling it, and going to another flea market. That’s why I also tell my students: every shit job I ever had gave me something that I now use in my practice.

So how did you choose the pictures to include in this new book? And how did you want to lay them out?

After seven years of being in New York trying and trying and trying, things moved fast. “Overnight success” that wasn’t overnight at all. I’d done pictures, I’d done word pieces, I was doing drawings. Something let go in me, and I started to be very creative. By the end of 1990, I had a German gallery who wanted to publish a book. I laid it out sort of like a magazine; there was no white space, no titles. It was this cool, little, anonymous-looking book that didn’t describe what you were seeing. The pictures were all full-bleed and laid out so there were interesting juxtapositions and a story being told.

A few of the pictures in this book were in that one. After all these years, I wanted to see if they hold up to being presented how “real” photographs are presented: one per page, white space, a title. It was an exercise in ennobling these pictures. Seeing if they could stand up to the white space around them. I think they do.

“Jack Pierson: The Hungry Years” is available via Damiani .