Ruth Ossai speaks with the same dynamism and self-assurance that radiates from her photographic subjects. It makes sense, when you realize those who stand in front of her camera often share her same DNA: Ossai tends to keep photography within the bounds of her family. Her desire to celebrate and empower her native Nigerian community is unwavering: when she collaborates with Western luxury labels, she refuses to compromise anything that does less than celebrate her roots and the localized pop culture references she loves.

Ossai returns to Nigeria often; in the meantime, she is based in Yorkshire in the UK, where she has a second life helping young offenders get back into the education system. She shoots portraits of them too, but hasn’t ever showcased this work. (She also photographs her white grandma and her church friends, and hasn’t shared these images with them yet either.) Ossai is self-producing a book with a stylist, featuring 50 images with eye-catching backdrops, called My Heart is Clean. i-D spoke with the photographer this weekend at Unseen Amsterdam, where she discussed reveling in her roots, importing and exporting style references, and the delight of the take-home photo.

So you typically shoot in a studio?

Yes; I work out of a pop-up studio. I shoot in east Nigeria — everyone here is my family member, except for a model shot in London. I was born in Nigeria, grew up in Nigeria, and went to school in Yorkshire. I like to do everything myself. I’m quite selfish like that. Someone’s like, ‘They want a producer…’ I’m like nuh nuh no! I’ll just do everything. Like I’ll cast it, I make the backdrops, paint everything, screenprint it. The carpets are from east Nigeria. This is printed on plywood; my uncle makes it. It’s a process.

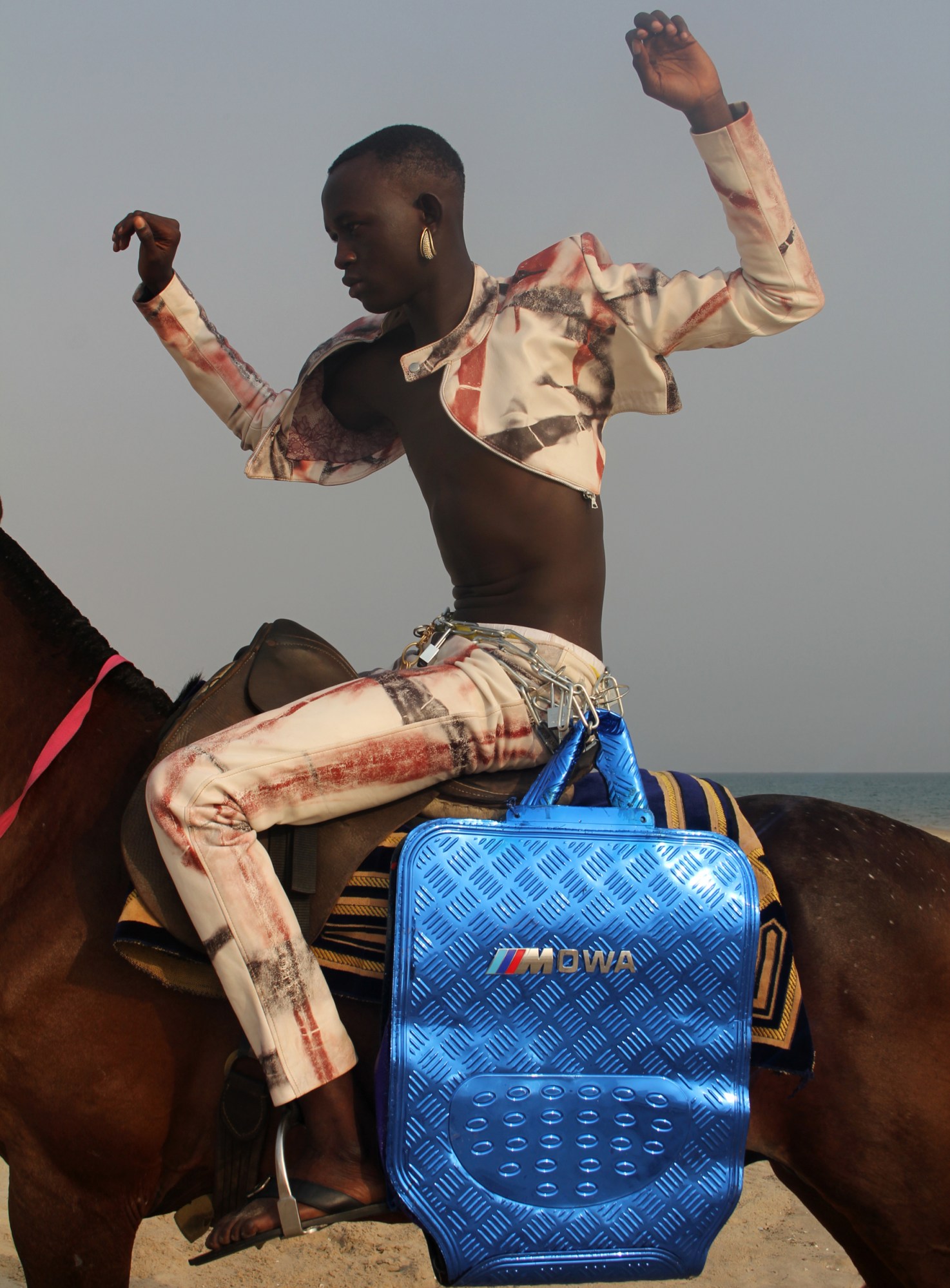

The work here [at Unseen Amsterdam] is a bit of a mixture. Three images are with a Nigerian menswear designer called Mowalola Ogunlesi. Her first collection was called Psychedelic, focused on 60s and 70s Nigerian highlife, which is a certain percussion and genre of music. These are stills from a music video. [shows clip from her phone] That’s only a tiny bit of it. I made the CD cover. This band is from my church. The crotchless leather pants are Mowalola’s designs… At first the guy was like, ‘I’m not wearing that’ but then he was like, ‘I wanna take it home.’ Basically in Nigeria, you have 20 music videos in one; they just roll. The video ends up being three hours.

I take inspiration from traditional Nollywood entertainment — we have all these television shows that have old Igbo gospel music videos and they have all these special effects, backdrops, greenscreens — of Heaven, of Jesus Christ — all this crazy Nigerian iconography. I always used to screenshot them when I was younger. I was like, ‘I wanna take a photo like this.’

How did you get started with photography?

I used to take pictures off my dad’s Blackberry of my family, because I wanted to show pictures of my Nigerian family to my Yorkshire family — being mixed-race — and vice-versa. I became a family photographer. Sometimes I think, ‘Oh my god; someone wants to buy a picture of my grandma for X amount! Why would somebody wanna do that?!’ But I do want to sell my work — I want someone to be proud to show my work in their house. If I sell, I would give a percentage, like, to these two boys [points to a portrait of her cousins] to pay for their school fees. My father is not from a creative background, but in terms of him appreciating my work, he now understands what I’m trying to do for my community. He’s like, ‘Go sell more!’

With family members, I imagine it’s quite playful to shoot them.

Yeah, very. Nigerians are quite effortless with posing. Sometimes we are, like, over-the-top. I’ll tell the boys to pose and they’ll pull out their own pose. It’s not something that’s forced. Going back home honestly melts my heart because we created this together. It’s always a collaboration with the talent, with their attitude and style. Nigerians are generally vibrant people; like when a Nigerian enters a room, you know they’re Nigerian. You can just tell. People are always like, ‘The styling is so good,’ but it’s effortless. On a Sunday people will dress up for church. It’s dramatic.

Everyone in Nigeria loves a home photo. They’re proud show it in their house. You will go to an event and you’re dressed — there are photographers that print photos there and then. So you pay to take a photo and at the end of the ceremony, you take it home. People come to me and are like: ‘Ruth, snap me!’ They’re asking me to snap them before I can even approach them. For us Nigerians, we love to take a photo home — I do it all the time! Like I’m on the beach and there’s a photographer there and I’m like ‘Oh take a picture of me and my friend!’ And then I pay X amount and then I take it home. My work is very memorial. I don’t share a lot of my work, because a lot of it is quite personal. This is not the only thing that I do: there are non-backdrop things, and I do collages. My dad’s a doctor and I photograph him doing his operations.

If you tend to work freeform with your family, how do you adapt when you have a client?

We did something recently for Miu Miu [for their Women’s Tales series]: Miu Miu Babes. There’s a Nigerian film called Nollywood Babes. Everything I’m inspired by is always West African, Nigerian particularly, though also Ghana and Senegal. Obviously there is restraint in terms of styling: we had to have certain looks… it bores me, but it is what it is! The stylist had restraints, but to be honest, I only really take on work if I know they’re going to give me crazy freedom. A lot of the clothes didn’t fit the women we wanted to photograph. It was based on Nollywood actresses, and they were quite big. The Miu Miu clothes are a specific size, which I don’t like. Because I like to photograph anybody, big or small; whatever. But we made it work. We had to undo the back and just not show it.

With Kenzo [for the spring/summer 17 campaign], none of the team came to Nigeria; they didn’t see the image till we handed it in, so they just let me do anything. Kenzo is not Nigerian style; it’s not what people wear in West Africa. At least not in my village. But they took it on like dressing up, and I just created all these things I like to do on Photoshop. Kenzo loved it! They ended up doing a zine. I wouldn’t take on a project if ‘it needs to be this.’ I’m quite selective — I say no a lot of the time, to be honest, if I think it’s not going to benefit my community. I think that it’s very important for photographers to be embedded in the context in which they’re creating. I’m not an outsider going in and leaving. Sometimes I’ve thought in the past, ‘They’re using me,’ like they think it’s a trend; that won’t benefit the black community. The budget had to go to a positive program within my community. I mean, they think, who am I? — ‘I’m only going to agree to it if you do XYZ’ — but they agreed, so….

That’s wonderful to set the terms.

There needs to be a more sustainable impact. With Kenzo, they gave the models the T-shirts; they sent hundreds of the zines for free. We had a party, and my assistant, who helped me with the Kenzo shoot, was able to fund his wedding. At his wedding, he was like, ‘I just want to thank Kenzo… [laughs]. They didn’t even know what Kenzo was before, but now everyone around my village is like: ‘KENZO! When are you coming back!’ I emailed them the wedding video.