To be queer in America right now is scary, says 23-year-old photographer Angelo Capacyachi, actually “if I’m completely honest, it’s paralysing.” In at least 20 states, a new wave of Republican-led legislation has put restrictions on LGBTQ+ lives, while a new poll shows a dip in GOP acceptance of same-sex relationships, almost a decade since gay marriage was legalised across the country. Trans rights have been particularly hard hit with debates over access to bathrooms and medical treatment proliferating in the mainstream media, and a Don’t Say Gay bill in Florida that aims to ban public school teachers from teaching about sexual orientation or gender identity.

The week before we spoke on the phone a woman was shot because she had a pride flag in her window. Before that O’Shae Sibley was killed for vogueing to Beyonce at a gas station in Brooklyn. And Angelo was at university the year a mass shooting took place at a queer club in Colorado. “Right now to be queer is just to be obviously resilient,” he says, “and having to see the world in a way that sometimes people don’t see you.” Angelo’s photo series Untitled (Utopia), which he made as part of his BFA photography degree at Parsons School of Design, envisions a queer utopia that combats the “repressive conditions of the present”.

The work draws upon the intellectual frameworks of the theorist José Esteban Muñoz, whose book: Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009), explored themes of queer futurity, world-building and the need to create a space that is limitless and all-inclusive. The book’s central thesis is that queerness is a future-oriented, utopian way of being and participating in the world that’s linked to the specific historical liberation struggles and the need for collectivity. “We may never touch queerness,” he wrote, “but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality.”

In intimate portraits of his friends, still lives and images that capture fleeting moments in his life, Angelo examines queer kinship, moments of transience, queer fragility and power. They show the existence of queer spaces and highlight the importance of these spaces to provide connection, care and solidarity. “When making this work, I wanted to expand what a utopia is,” he says. “It’s important for the queer community to show how expansive it is.” Adding, “the idea that there is one is actually pretty reductive,” he says. “Because I feel like there are so many facets of what it means to be queer, especially now.”

Growing up in Rutherford, New Jersey, Angelo wasn’t exposed to the full spectrum of queer identity: the suburbs were heteronormative, conservative, white and cis, he says. “But at the same time, I had the internet. I had New York.” Angelo moved to the city when he was 18 and flourished, expanding his understanding of what it means to be queer.

In part, it was proximity to the artists and works that made queer people visible in art that helped him understand his own history, and how previous generations of LGBTQ+ people have carved a space for the queer culture that we now take for granted. “There’s so much weighted history about what it means to make images in New York,” he says, referencing artists like Nan Goldin, Jack Pierson, Mark Morrisroe and David Armstrong. Robert Mapplethorpe, George Platt Lynes, Peter Hujar and Greer Lankton were part of New York’s queer history too: able to transcend oppression through art and accomplish great things during its most difficult times. It’s important to understand, says Angelo, “what art was here, and what has been made and what can be made.”

He points to the challenges the community faced during the AIDS crisis, when Reagan-era politics began placing blame on men-who-have-sex-with-men for their choices. Many artists used their body for their art, and showed the pain the illness caused. “It was so hard to see,” Angelo says, “but also, there’s this beautiful tenderness about that moment of looking at that work.” There’s one self-portrait in Untitled (Utopia) taken in the mirror after getting the Monkey Pox vaccine. “I was interested in what it means for the government to kind of isolate queer bodies, or queer men.”

At that time, there was no real knowledge about the virus: “it was so unknown,” he says, drawing similarities to the AIDS crisis in the 80s. “The only information they gave about it was that it was impacting men who have sex with men, and it felt very reminiscent of that time.”

“I was very isolated,” Angelo adds. “I had no one to really discuss Monkey Pox with — I didn’t have any queer men in my life, I had no structures of support… it was a very raw, tender time for me.”

“It’s very easy to feel isolated and feel alone within all of this because it seems like the world, the government, especially in America, don’t really care. The fact that it’s very unsafe for queer folks, and especially trans folk, right now, [means it’s important for queer people] to be constantly building community,” Angelo says. “I’m always kind of revising, rebuilding or renegotiating what it means to be seen or feel seen.”

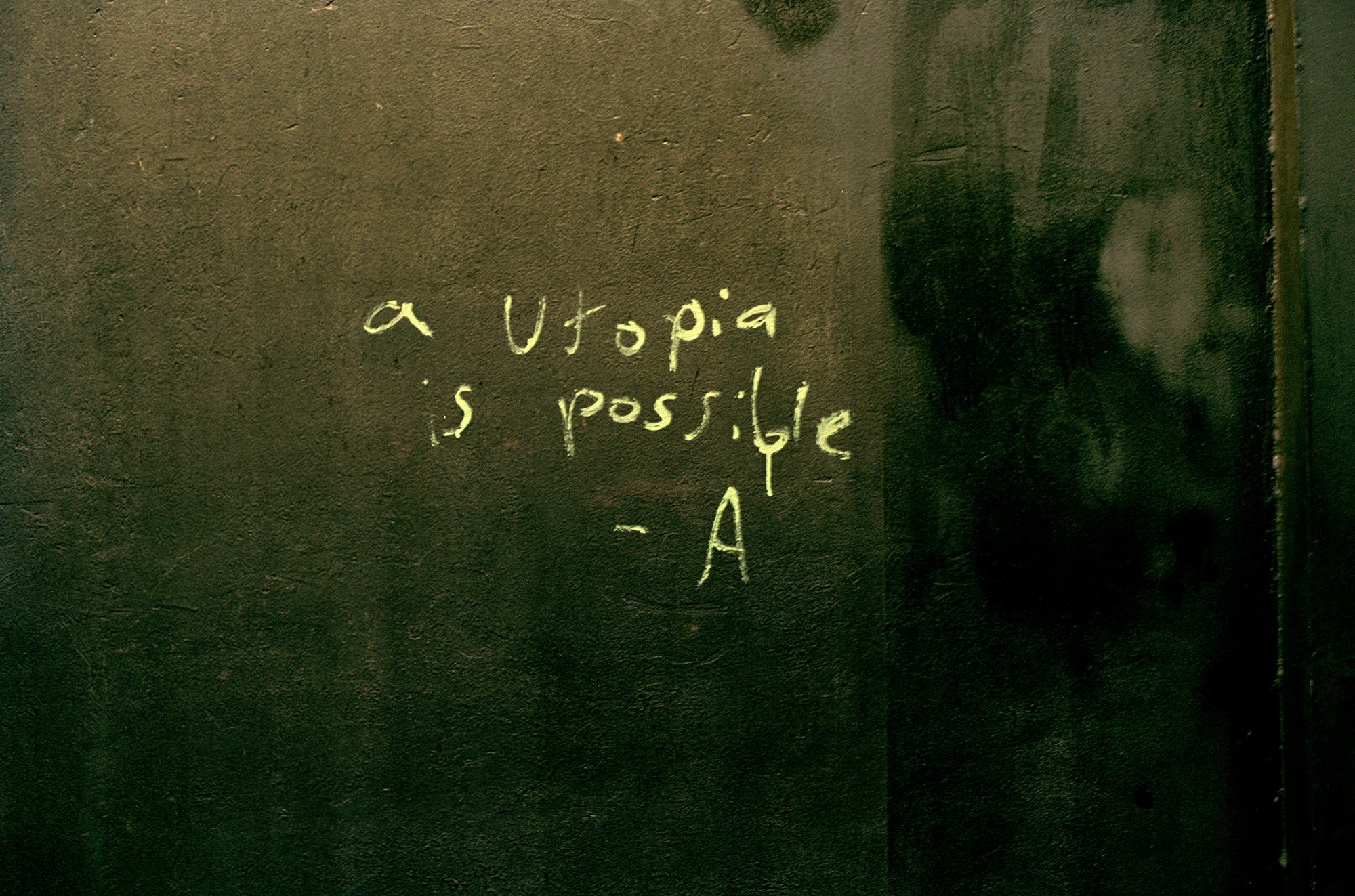

As a result, many of his images capture something that is temporal: shadows, residue, smudges on mirrors, imprints and graffiti scrawl in the Lower East Side that reads “a utopia is possible.” Things that remind him of “traces of human contact that allude to temporalities that then allude to futurity,” he says. The work is reminiscent of the banal subject matter made famous by Wolfgang Tillmans, whose retrospective was on show at MoMA, while he was studying at university.

In both artists’ universes, nothing is too small to merit attention and beauty in overlooked details. A picture of an elevator in his apartment shows smudge marks where hands have been: “you could feel the contact and it reminds me of a club bathroom: this inter-residual space… I saw it, [and] traced it,” he says. “There’s so much past, present and future in that one photo.”

Angelo’s project is ongoing: “I think I will always be thinking about queer futurity,” he says. “But I was exhausted thinking about the future all the time. It kind of made me ignore my present. And honestly, this article or even just this conversation, might even be a good end.”

Credits

Photography Angelo Capacyachi