Talia Chetrit is all about the female gaze. The photographer’s work, on view at the Zaha Hadid-designed MAXXI museum in Rome, includes a mix of 90s-era archival images taken when she was an adolescent and contemporaneous images in which she explores her own sexuality. She is currently a finalist for the MAXXI Bulgari Prize, previous winners of which include Vanessa Beecroft and Francesco Vezzoli.

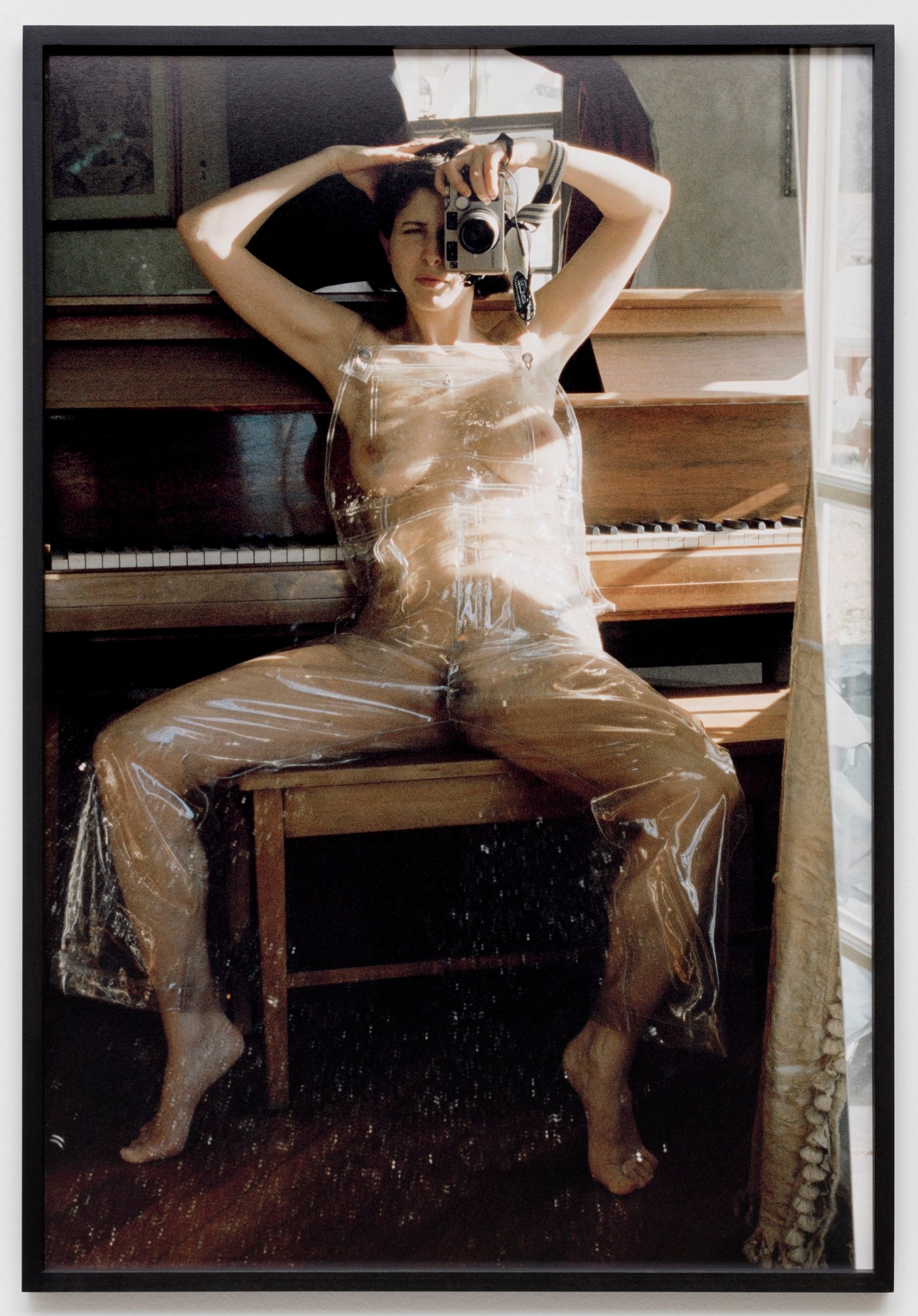

Intimacy, through Chetrit’s lens, is examined from various perspectives. In one self-portrait, Chetrit deems herself “both completely transparent and fully covered” while outfitted in a clear plastic Norma Kamali bodysuit; in another, one glimpses her in flagrante with her boyfriend, the cable release emphasizing the self-awareness of the studio sex voyeurism. There’s the innocent naturalism of an insect idling on a belly (“It is such a private moment, when a fly lands on your skin,” she tells i-D), and a heavily painted self-portrait in collaboration with Corey Tippen — the makeup artist known for Antonio Lopez and Andy Warhol shoots in the 70s. There are middle-school pictures of Chetrit’s friends who, before they grew up to be environmental lawyers and documentarians, sported MTV logos, licked candy, and orchestrated fake murder scenes (“this is where I realized we could play with fiction — that anything could be in a picture, and it could potentially be real,” she says).

i-D spoke with Chetrit about power dynamics, contextualizing girlish behavior, and the startling nonchalance people feel towards Robert Mapplethorpe relative to female genitalia.

How did you select this edit?

I decided to mix together certain bodies of work. There are pictures I took in middle school, in 1995-1997, of my girlfriends at the time; basically we’d come to my house after school and dress up — or take our clothes off — and just play. I wanted to revisit those images because there was something about them that really showed a certain vulnerability. One friend is sucking on a lollipop — we understand, at that age, that that’s sexy, and we wanna do this for the photo, but we don’t really understand what that reference is. There’s a misunderstanding of representation, but an understanding of ourselves. I thought that was really interesting, especially since I was the same age [as her]. There’s no threat — there’s nowhere these images were going to end up. Had it been today, these would go online; imagery has a different relationship to the present.

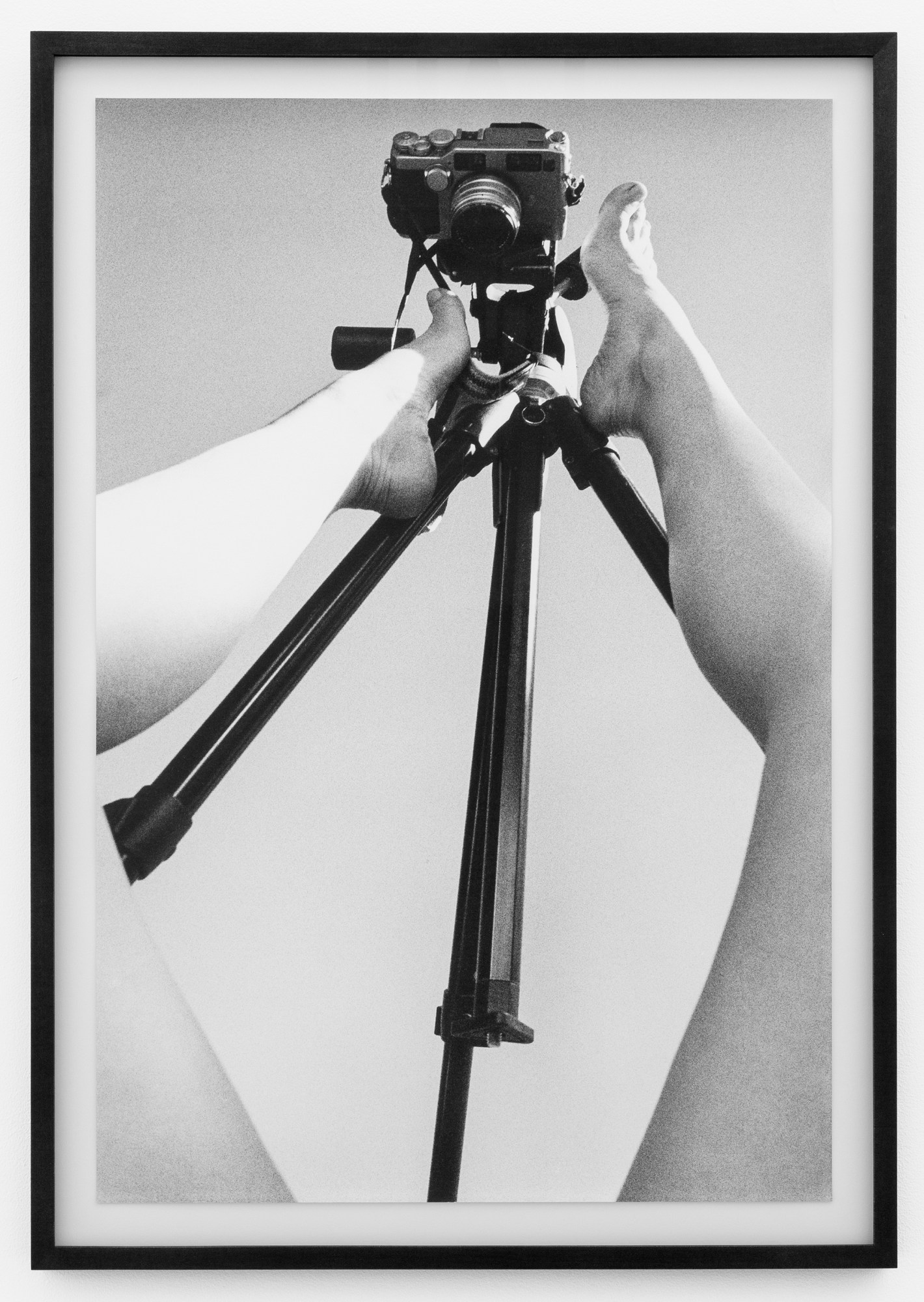

Another part of the exhibition articulates a certain approach to sexuality and images from an adult’s perspective. In the sex pictures, you often see a cable release, so you see that I’m in control, that this is a performance that’s being made for the camera. And then there’s a video of my parents that I shot a couple years ago. There was a dynamic between the two of them, and between the three of us, that I’d never experienced before.

How do you negotiate being both subject and the photographer?

When I’m in the photograph, there’s no power dynamic. There’s a freedom there, as the subject. I use myself for that — to have access to that. I started taking pictures of myself after I did the video of my parents. There was a feeling of having really exposed them, there was so much vulnerability, and I feel like I had no right not to do it to myself. I started doing the “Bottomless” series thinking it was more comical, like a parody of a female photographer.

Was it always clear to you that photography would be your creative practice?

I started developing my own film when I was about 13. It allowed me to engage, it gave me another way to interact. When I went to art school, I did a lot of painting, a lot of performance. I was less interested in the practice of photography than in the ideas that surround photography: how it can alter reality, yet is badly defined as having some relationship to truth. I liked [playing] with the poetics of that.

The Bulgari prize seeks artists whose work has political resonance. Do you think of your work as political? Does being a female artist necessarily have a political component?

It does. The representation of women, obviously, is something that all women deal with their whole lives. The power position of being the photographer is something I’m often using as a metaphor to talk about power positions in general. I think photography is always a metaphor for feminism, in a weird way. And I hope that the work provokes an interest to engage in conversation.

Sex is a loaded subject, but a woman who puts sex out there — by her own means — is not always well-received. Have people misinterpreted what you intended by showcasing female sexuality?

One thing I was shocked by: I showed the vagina pictures in an exhibition where my picture was hanging next to a Mapplethorpe image of a whip coming out of [the photographer’s] asshole. This whip looks like a massive shit [laughs] and he’s looking dead into the camera. In my piece, to the left of his, is this tiny image, you see a closed vagina, and takes up 0.02% of the frame. And I watched women at the opening look at my picture, see my vagina, and make this disgusted face. And then [they would] look at the Mapplethorpe picture — which, I love that picture; I think it’s the most aggressive picture that exists — and not have any reaction. I never thought that would happen. When I was making those pictures, when I described what I’d done in the studio that day, women would say, “Oh, that sounds cool. But I have a weird vagina.” And I was like, “No, I have a weird vagina. Everybody has a weird vagina. Nobody even knows their vagina.”

What spectrum would you even use to know the weirdness of your vagina?!

[Laughs] We don’t know vaginas! I thought that was a funny reaction.

What prompted you to revisit images from when you were young?

I really liked the way those images changed so drastically, especially with sexting and Instagram. The images in themselves haven’t changed in twenty years, but I really liked seeing how we were trying to represent ourselves — which I couldn’t see when I was taking them. There’s one image where a friend was wearing jean shorts, a white t-shirt, and makeup that she certainly wasn’t wearing at school that day, [and standing] against wood paneling. I looked up the year of the Calvin Klein campaign, and it was the same year. I was thinking: I wonder if I knew that campaign then. I think I must’ve.

Ironically enough, now you shoot your own campaigns, for Acne Studios and Céline. How is that a different creative exercise to your self-portraits?

I really like the adrenaline rush that you have when you’re shooting. I try to keep my sets really closed, but there’s often an audience. You just have to work all day, and you make do with the situation you’re given. It all comes down to this one moment, so you’re really pushed to problem-solve. Whereas the work I make, if I have an off day, I have an off day, and it really doesn’t matter! Most of the shoots I’ve done, there’s all this conceptual research beforehand, and then you just have to let all that go and react to a live situation. I really enjoy it.

Has this involvement in fashion photography influenced your own work or understanding of representation?

I think it has actually changed the work quite a bit. In fashion, the image is so important; it pushed me to counteract that a bit. There’s an image of a young girl that I shot for a campaign, whom I’ve been photographing since she was seven, and she’s now 11. The day before the launch of the campaign, they ended up using somebody else and cut out the images of her because they felt concerned about, as they said, “the Harvey Weinstein climate.” Which I thought was so… inaccurate, in a way, to feel afraid of that. Harvey Weinstein is problematic because of how he treats people, it’s not about his work — and this young girl is my long-time muse. She’s behaving like herself. There’s a sexuality that we put onto the image, but that’s something that we are doing. We can’t help it, and I understand that, but it has nothing to do with her — she’s acting like a little girl. I really like that image, for that reason.

Do you think there’s too much policing about the parameters of propriety?

No, I think everyone has to figure out their own boundaries. That’s the important point — that we need to decide these things for ourselves. And it’s all valid. One of my pictures from middle school is of two girls nude in a bed. That image, had I taken it now, would be incredibly problematic. The image could be the same, but it’s protected by the fact that I was their age then. I’m interested in how that’s allowed there, and potentially not allowed now.

The work of MAXXI Bulgari Prize finalists Talia Chetrit, Invernomuto and Diego Marcon are on view in Rome through October 28th.