The changing tide of opinion towards brutalist architecture has had a profound impact on London’s landscape over the years. Design borne out of a post-war necessity to accommodate a rising population amid an economy in recovery has been recognised for its artistic merit, listed by councils, churned through a proverbial branding agency and come out the other side an opportunity for developers to reframe what luxury living is — sparking Facebook appreciation groups and derivative Instagram shots in the process. Though some developments have fallen victim to demolition (nothing could exemplify the paradox of brutalist architecture more than the fact Robin Hood Gardens was underfunded and ultimately demolished against the will of its residents, yet a small piece of it was preserved and exhibited at the Venice Biennale) many of the city’s most derided estates are now considered among its most desirable postcodes. Centre Point. Balfron Tower. The Economist Plaza. Your MCM’s fave #Sundays spot, the Barbican.

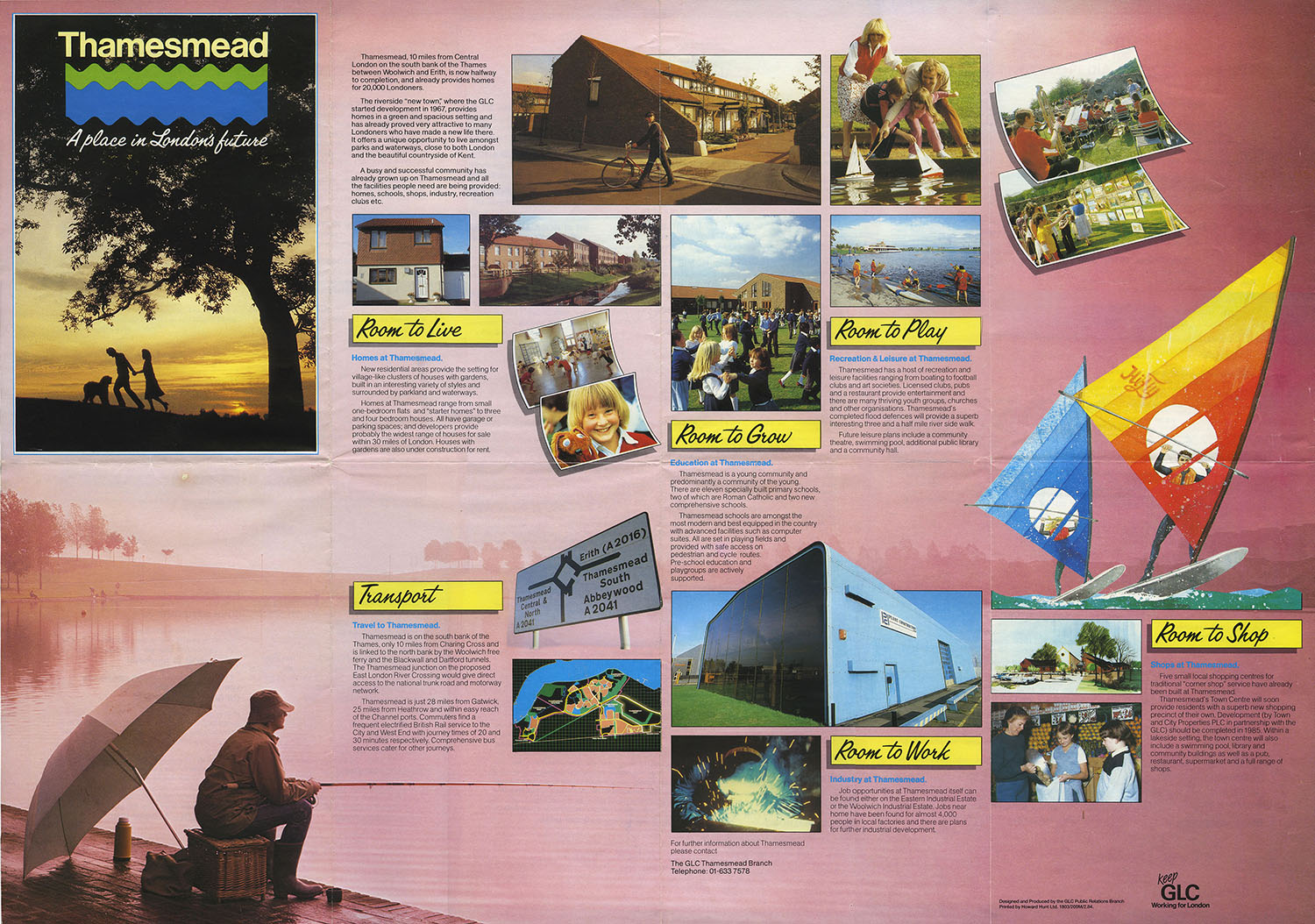

Thamesmead, a property development to the east of London, built in the 1960s largely as council houses, is the latest on the cusp of an image overhaul. Billed as “The Town of Tomorrow” when it was first constructed, the vast micro-town was London City Council’s response to the city’s post-war housing shortage. Built on the Erith marshes beside the south bank of River Thames, the concrete construction gained notoriety after completion for its experimental design — a labyrinth of angular, asymmetric balconies, bridges and tunnels — and a drastic departure from the Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian design that suffered significant destruction in both world wars. Largely facing derision amongst politicians, architects and academics, in 1971 it reached global fame, as the backdrop to a violent crime spree in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (see also: Aphex Twin’s Come to Daddy video).

Ignored by developers for the last 50 years thanks to its lack of direct rail or tube line into central London — relying instead on bus — the arrival of the Elizabeth Line to the neighbouring Abbey Wood station will soon create a fast route into the city and a viable commuter link. Now in the hands of the Peabody housing association — who are leading a £1 billion regeneration of Thamesmead and neighbouring Abbey Wood and Plumstead — change is imminent for the 40,000 residents of a once-maligned community. But while claims of ensuring “improvements to housing, green spaces, waterways and economic prosperity” from Peabody seem promising, where regeneration goes, out-pricing soon follows. Turning architecture designed under necessity and selling it at a premium predictably and depressingly often leaves residents with an eviction notice and the offer of much-less practical alternative.

Author Peter Chadwick wanted to explore and celebrate the unique details of the community with his new book, The Town of Tomorrow: 50 Years of Thamesmead. “The photographer Tara Darby and I made regular visits to Thamesmead between December 2017 and December 2018 on a monthly basis to document, photograph and to meet and engage with the residents,” he explains of the project. “As outsiders we felt it was very important to make connections with people. From the outset Ben Weaver [designer and publisher of the book], Tara and I had a clear vision that the residents past and present would underpin and define the book.” With Thamesmead celebrating its 50th birthday last year, this combined with the changes happening in and around it made it “the right time was right for a book to celebrate and document the history of this remarkable place.”

Was this project motivated more by architectural or social inquiry?

Growing up in Middlesbrough in the 1980s, Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange was banned. A few years later when I eventually saw this film, I became fascinated with the sets and locations, particularly Thamesmead with its stark white concrete veneer. I first visited 11 years ago, armed with a view of Thamesmead shaped by cultural references that included Kubrick’s film, Aphex Twin and another, gentler 1990s film set in Thamesmead, A Beautiful Thing. Self-generated projects and a series of posters I made in response to archive GLC sound recordings and public information films followed. These were made in particular as response to the architecture, utopian vision and isolation of the place. As my visits to Thamesmead became more regular along with meeting local residents, my focus widened beyond these early entry points.

How much of your existing beliefs and opinions of Thamesmead changed over the course of this book’s creation?

So much. Thamesmead has a deep, rich and fascinating history including the former Royal Arsenal munitions dumps, a traveller community dating back to before the world wars, the re-appropriated new town plan from Hook in Hampshire, an unrealised marina development that wouldn’t have looked out of place in the South of France, one of the largest Ghanian communities in the world outside Ghana… The durability, strength and pride of the people who have lived or currently live there shines through. My early thoughts and opinions shaped by music, film and television quickly changed the more people I met and spoke with on my many visits there.

There are a lot of historical landmarks and political changes that have shaped the community of Thamesmead. Did you get a sense of this spending time there and engaging with residents?

For sure, there are a number of strategically placed relics from the former Royal Arsenal dotted around Thamesmead that embellish this new town’s history and a wonderful story about the Thamesmead town clock tower that was originally in Deptford Dockyard and arrived in Thamesmead via the River Thames on a barge. Depending on who you talk to, there is a wide range of viewpoints in response to a constantly changing political landscape. Up until the last few years what has shaped a tangible independent and combative local spirit has been fuelled by its location, isolation and poor transport links to central London.

Does it feel like a microcosm of London or something quite different and unique?

Perhaps in the 1970s it was a microcosm of London, in particular for those rehoused and relocated predominantly from the south-east and east of London. In more recent times I would say it is more like a microcosm of the world, with large communities from West Africa, Vietnam and host of European countries living locally.

How accurate is the depiction of in films and television and have we been presented with skewered view of its design, atmosphere, community?

I met a lovely elderly lady many years ago who asked me why I was taking photographs of a concrete walkway, a reasonable question I guess in light of my camera focusing on an expanse of weather beaten concrete. She tutted at me and said “There is more to Thamesmead than A Clockwork Orange” and went onto tell me how much she loved Thamesmead with its wide open green spaces and lovely walks. This pricked my interest and was the entry point to delve further beyond my viewpoint that most notably had been shaped by what was, after all, a less than two-minute appearance in a Stanley Kubrick film.

Does this have an impact on the way the area is viewed by the wider public?

Yes, there is a narrow viewpoint of the place which hasn’t been helped by its on screen persona. Spending a lot of time there and getting to know people with such diverse backgrounds, beliefs and faiths has been wonderfully enriching for both myself and the book. Growing up in a town in the north east of England surrounded by concrete and heavy industry, Thamesmead felt familiar, not hostile or foreboding as some people see it. For many people it is a place they call home. The same can be said of many similar places and new towns around the UK.

Do you think it’s an example of clever, intuitive design or an era of architecture that shouldn’t be revisited?

It was certainly clever and intuitive in response to the demands of how to reclaim land and build on it. A very bold plan that didn’t manage to fulfil the utopian vision of the Greater London Council, London City Council, planners and architects. A vision that has had to adapt and evolve in response to an ever-changing political landscape over the last five decades, a lack of money and the demise of the GLC have also played a major part. Perhaps it is less about a particular era of architecture not being revisited and more about having a sustainable infrastructure with the support of and best interests of a government to fund and maintain a community.

Do you think the future of Thamesmead looks completely different?

With the Peabody redevelopment of Thamesmead and the forthcoming opening of the Elizabeth line, the place itself and residents are going to be so much more connected to central London than ever before. This will no doubt bring numerous possibilities and challenges ahead for them. I do hope that those living there are able to benefit from what are on paper are exciting changes and those that move there in the near future further add to this vibrant and diverse community. Thamesmead can once again be a ‘Town for Tomorrow’.

‘The Town of Tomorrow: 50 Years of Thamesmead’ is available to order from HerePress.