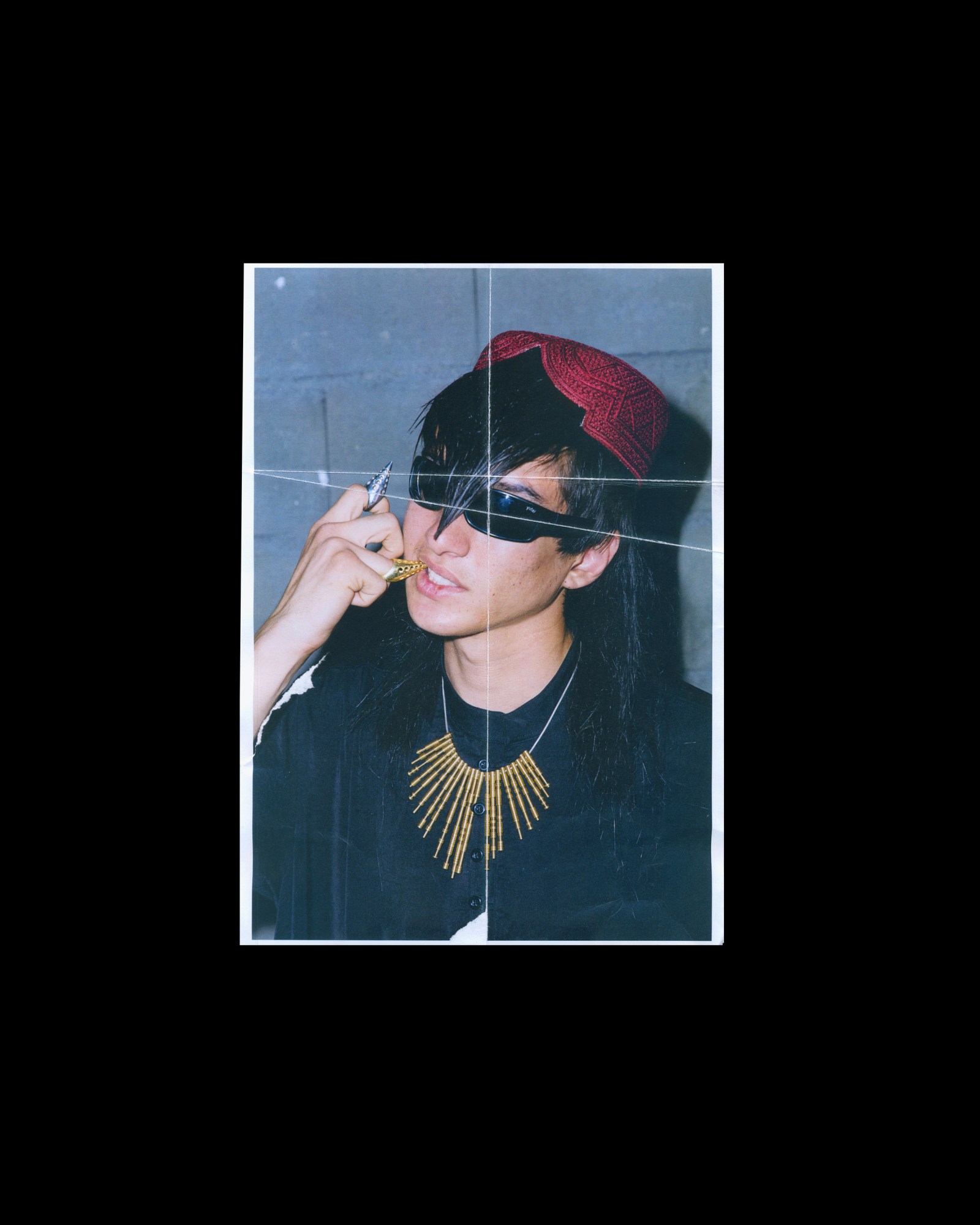

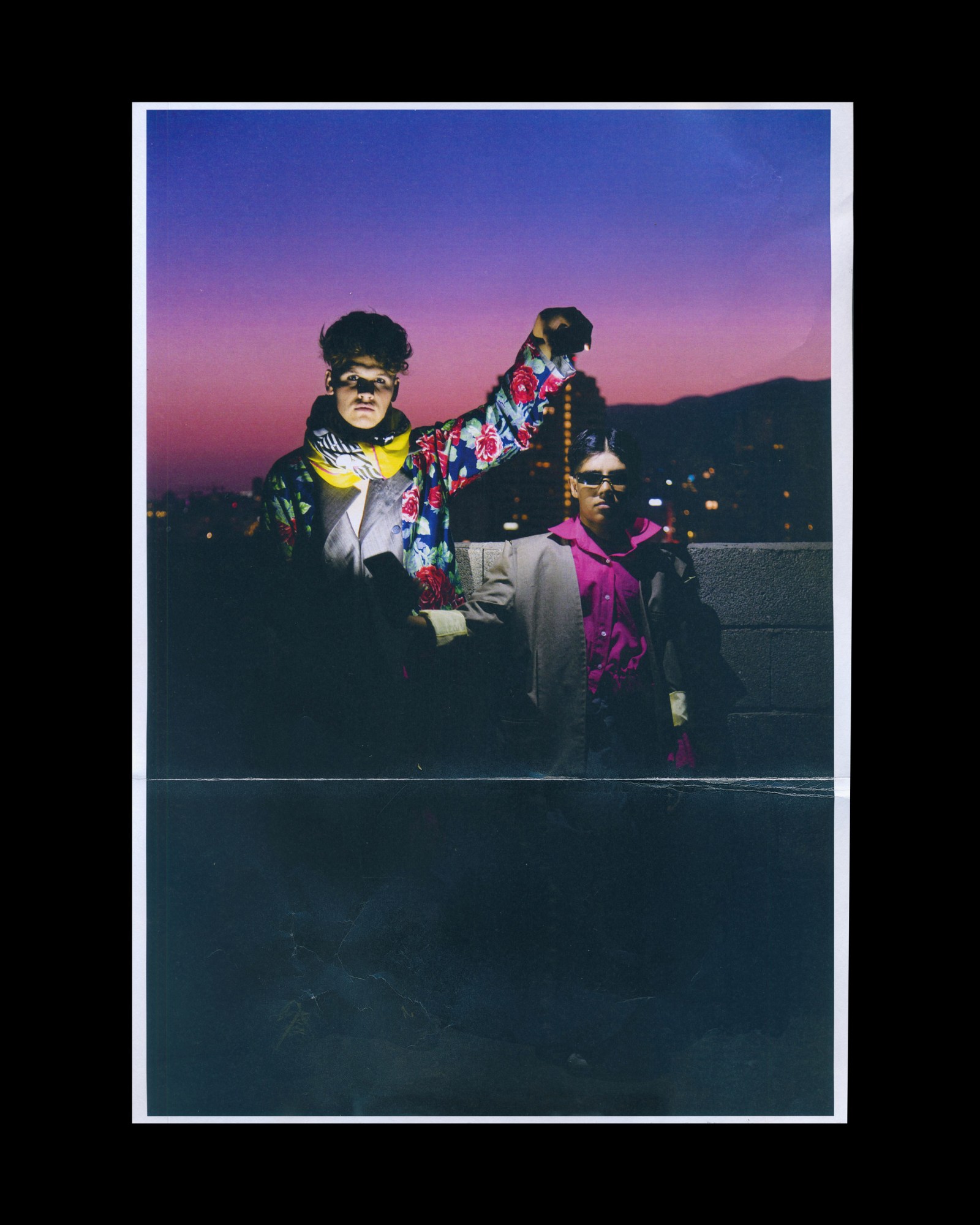

For young artists in Tehran, censorship defines their creative expression. Photography has always had the power to turn audiences into witnesses, and Iranian artist AliA takes the process one step further. He uses the practice to expose the dreams of his friends and instil hope. The images look as though they have been torn from a magazine; some have visible folds, others are fading. They are all live memories—remnants of a youthful imagination forced to hide in shadows, abandoned buildings and forgotten alleys.

In an oppressive climate, where just last year twelve models were jailed for “encouraging moral degradation” and “exhibiting Western fashion online and on social media,” AliA’s photography flaunts his subjects with urgent protest.

In the 1960s, Iranian dress drifted from brightly coloured traditional garments, layers of flared skirts with intricate hand beading and embroidery, to a Westernised look riddled with European influences from the era; neck scarves, short skirts and bell bottom pants. After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the Ayatollah declared that wearing the chador was now a moral duty. During the early years of the Islamic Revolution, dress laws were fiercely enforced and monitored; forcing women into veils and long overcoats.

Behind closed doors, at private parties, creative expression blossomed among the cities pariah, AliA celebrates this undercurrent.

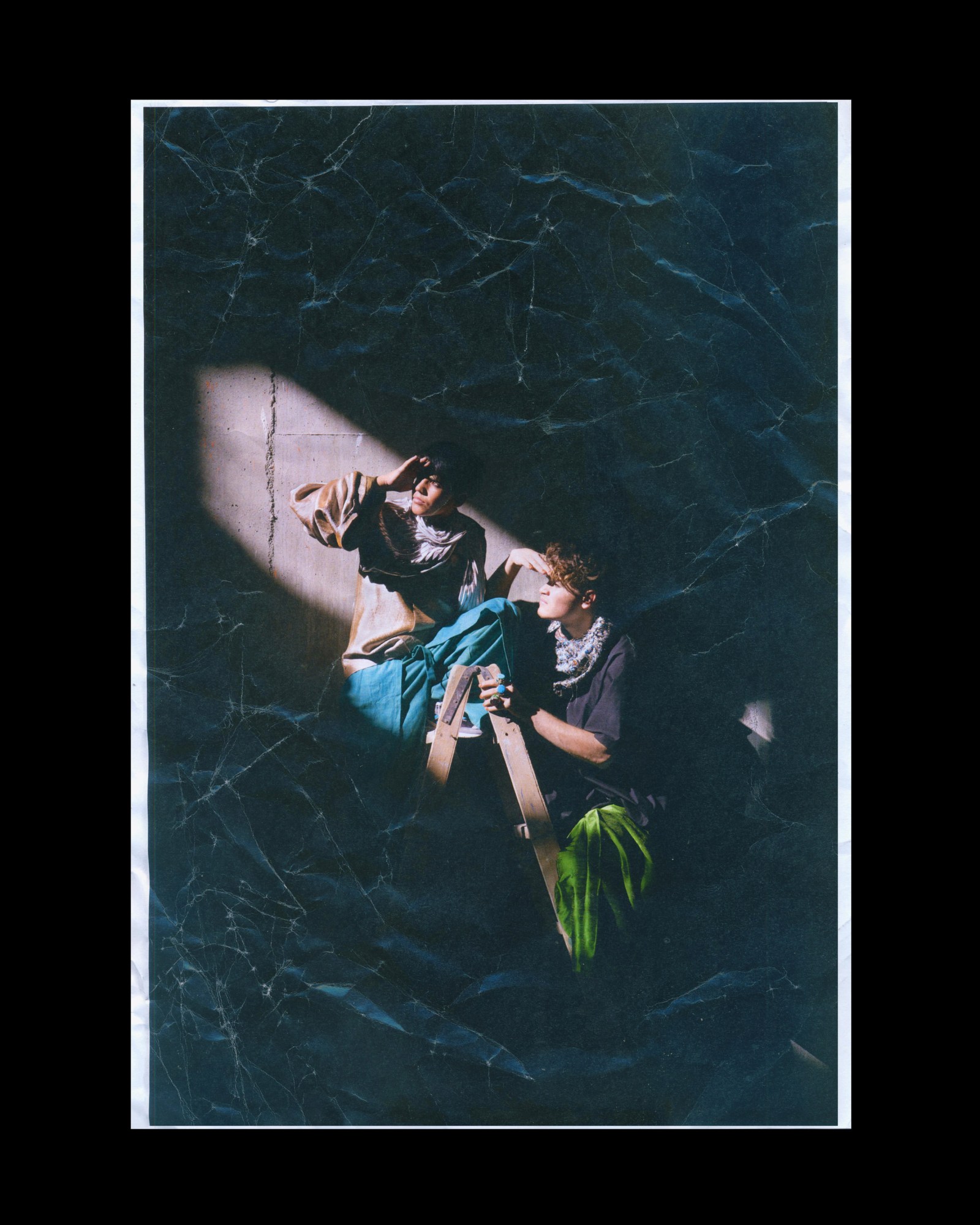

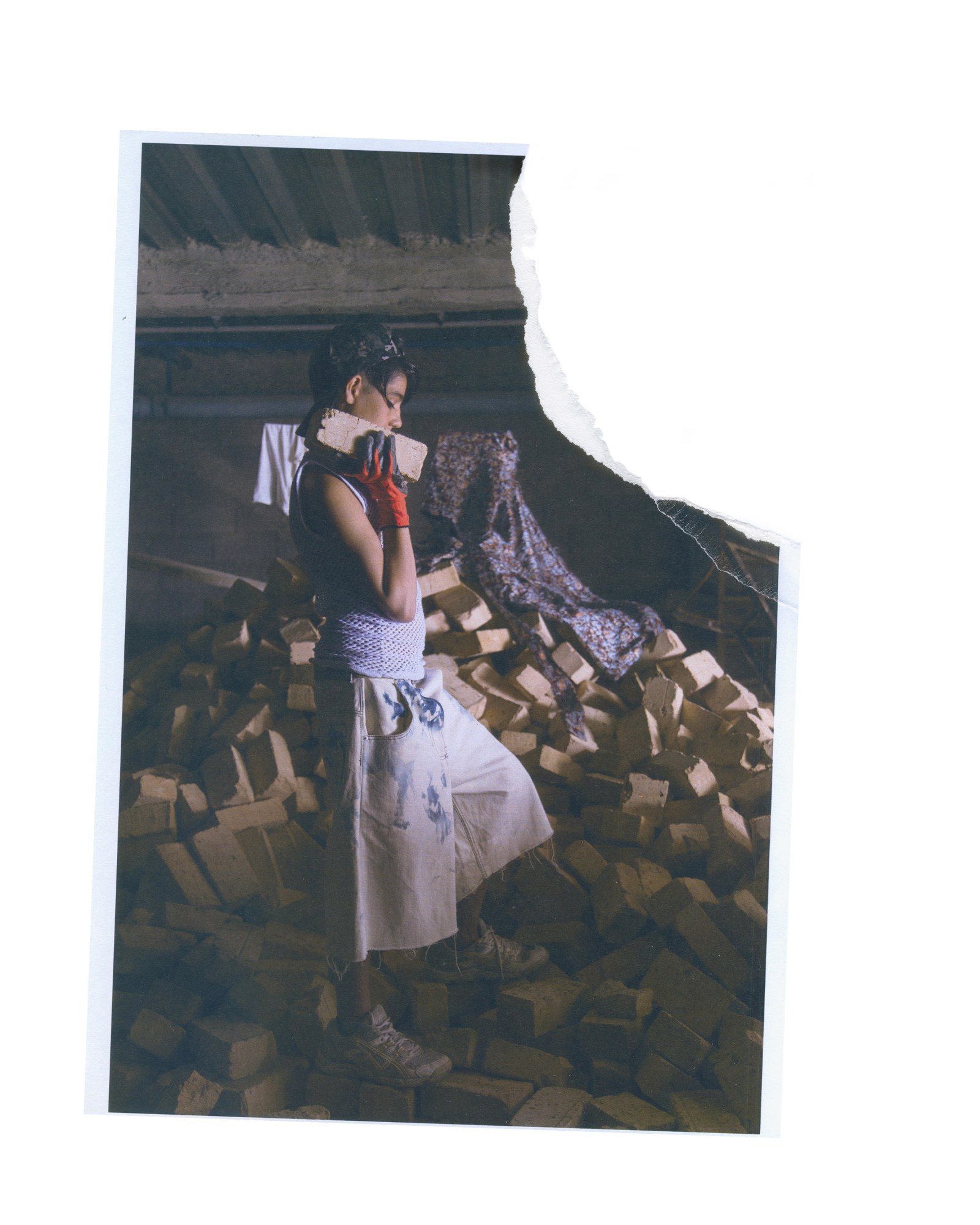

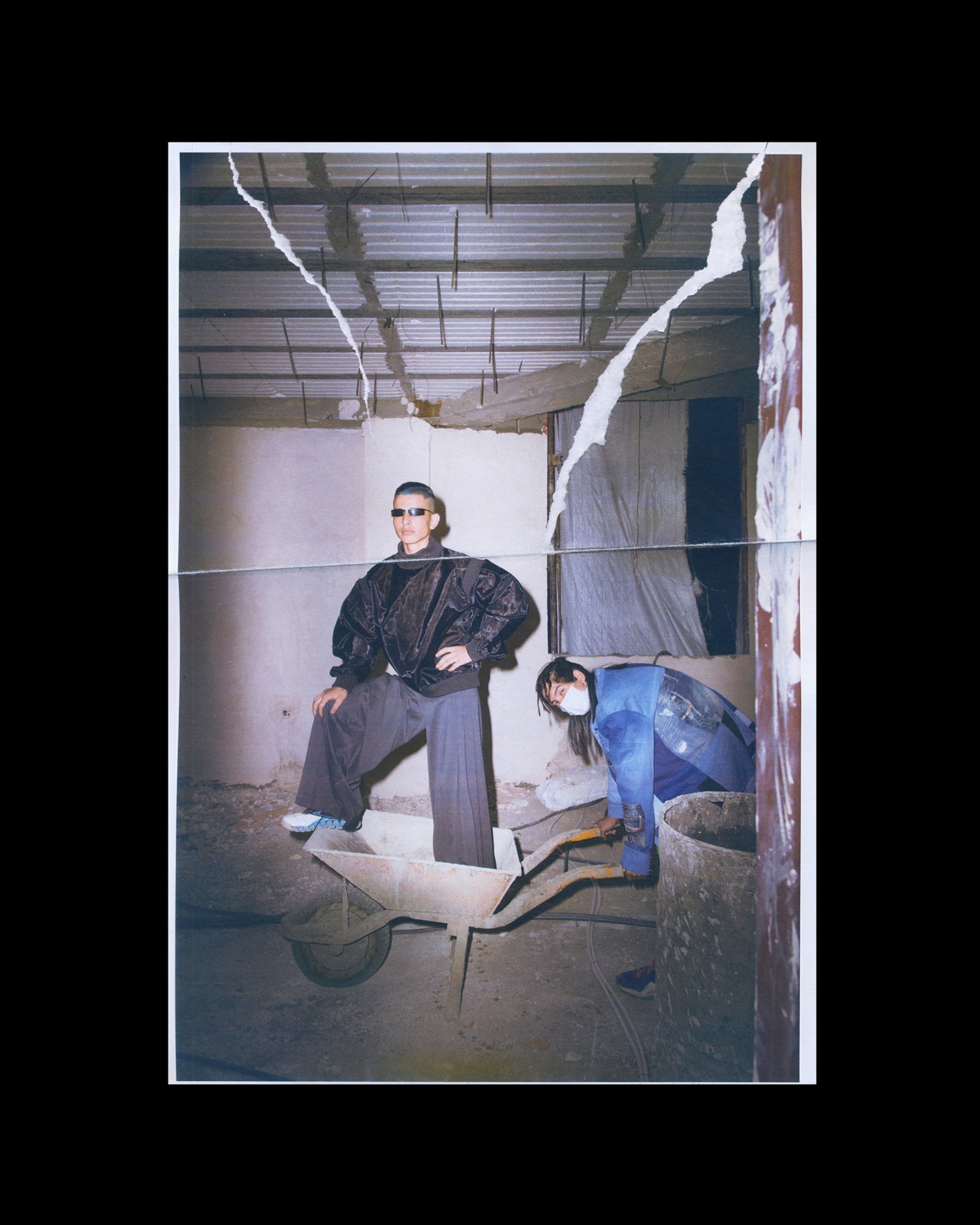

Displaced people and garments intertwine in AliA’s work to tell the story of Iran’s underground scene. In the series Kaarzaar or Battle, Afghan refugees pose in construction sites, where they spend their days as labourers, in garments that scream in tie-dye layers and shapes that reveal their bodies with war-torn cuts.

When did you start making art?

My first experience as an artist was in high school when I started making alterations on my clothes, such as ripping them or painting on them. Soon my friends were fascinated and asked for the same changes on their clothes too. So that became a sort of income for me at that age.

Do you remember the first photograph, garment or artwork that really moved you?

When I was really young there was an ancient box at my grandparents’ house, full of interesting things. Some of them were old fashion magazines like Burda that my aunts collected before the Islamic revolution in 1978.

For me, the most fascinating photos were the editorials that had been censored by someone with a thick black marker, for instance, because of revealing women’s nipples. I guess censorship was a very impressive visual shock and also inspiring spark.

What makes a good photo?

A good story to spread. A good way to go. There’s a Persian proverb; “What arises from the heart will, of necessity, sit well with the heart”.

How do you incorporate that into your process?

In Iran, the process of production and ideation depends on the kind of limitations we face at that time. We need to consider those and then decide which project is achievable.

I believe a concerned human can use their concerns as creative fuel. We should be honest to ourselves; there is no shortcut to reach a good idea. I think I do not live in an ideal world and all I can do is accept that. This acceptance made me see some things I could not see before and this has led me to new forms of inspiration.

What is the scene like, the word “kaarzaar” is often cited in your work, tell us about the struggle?

Unfortunately, since the Islamic revolution, the fashion industry’s infrastructures do not really exist in Iran. Thus, we should consider the specific standards, we need to redefine the production process based on current condition in the meantime and be prepared for new surprises or barriers. Like, there is no fashion agency in Iran, so even the first stage of casting takes a very long time because we have to do it with the help of friends or street interviews.

When we were dealing with casting one of the boys was deported from Iran and to be honest, we knew we had to be ready to face more of them leaving us during the project. Finding a shooting location is another problem because it’s illegal and people could barely trust us.

Is it difficult to source the garments?

For this project, we really wanted to use Iranian designs. Most Iranian designers live abroad and some of them are in the US, and that means they could not send us their work because of the sanctions that have been applied – even on posting envelopes.

We really are not living in a good social or political condition specifically for people who are concerned about these issues. But people are doing their best to pass the limitations with more creativity than ever.

How does your close proximity to war influence your practice?

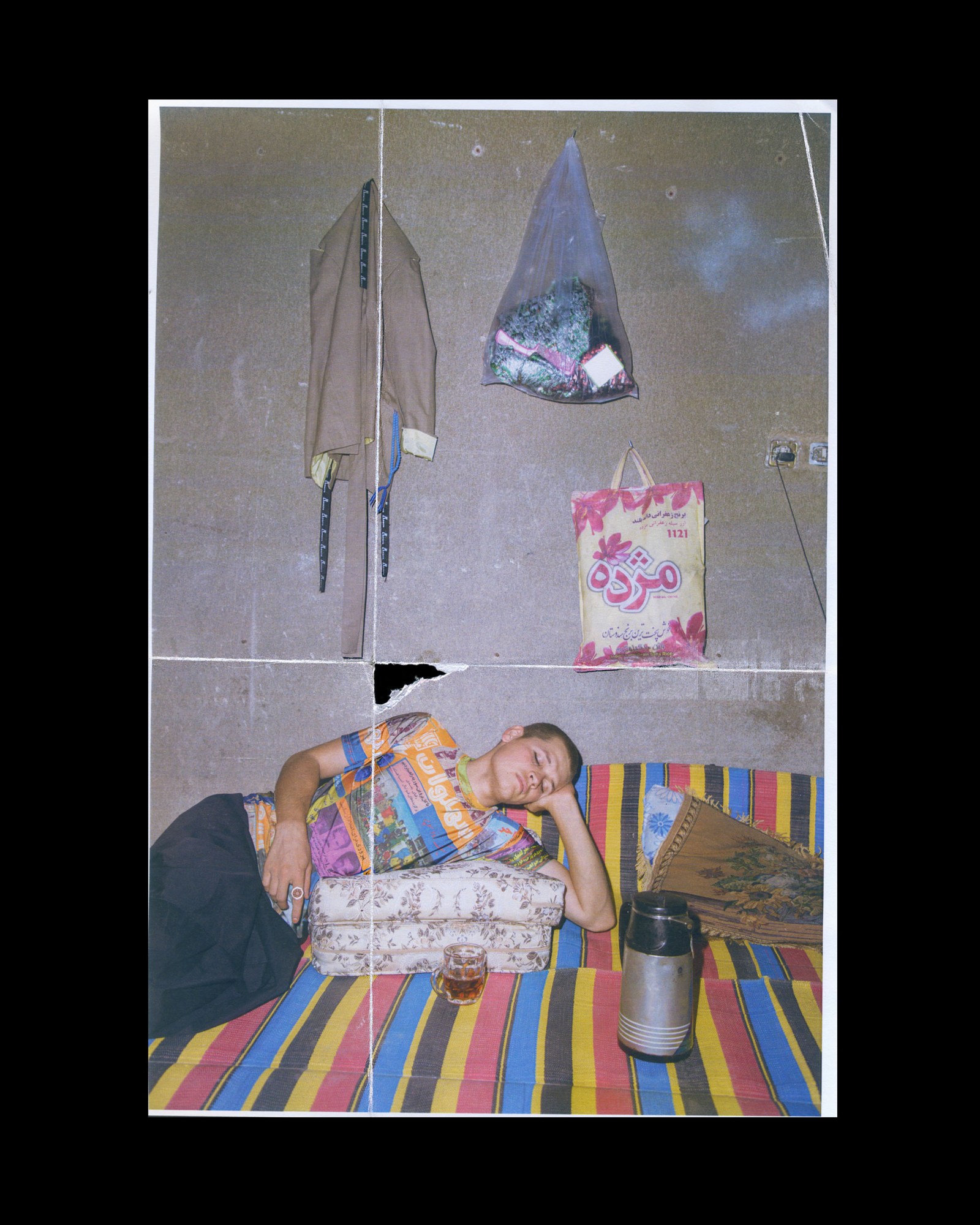

As a Middle Easterner, I can say from the very first moment of people’s lives, they can feel the “kaarzaar [battle]” they are dealing with. We can feel the shadow of war, which is moving from one country to another in the Middle East. Somehow, we have gotten used to it and are just living our lives.

Can you tell me about your “kaarzaar [battle]” collaboration with young Afghan refugees?

When Europe opened the borders for refugees, I was working at a café as a cook and had the chance to get to know some Afghan’s who were working there. Kaarzaar was not just a quick idea; working with those Afghan guys for a while was inspiring to me. I would love to capture and show their tireless efforts by themselves.

The most difficult part was finding Afghan models, making them trust us enough to cooperate in the Kaarzaar series. Afghans in Iran usually work illegally; they don’t have visas, work permits, and are often under-age. At first, our plan was to use Afghan folk music, but then I saw an Instagram video of an Afghan rapper who was rap battling in a park in Tehran. I snuck in to one of their meetings and watched them freestyle. The rap music was used in the final product.

Besides being our models, they directly took part in the whole production process. You can see their actual footprints on the printed photos, or they would come up with some stylistic ideas, putting on some clothes in their specific way of wearing, or they helped set up the scene. In fact, their strong presence gradually tied into the project. Some of these people had been deported several times from different countries, specifically European countries, but they had this surprising hunger to reach their dreams and it was inspiring.

What are some of the creative differences between Iran and Afghanistan?

I believe the similarities are stronger than the differences; they both have huge diversity within their culture and this cultural diversity is visible in some areas such as clothing, music, and make-up which are amazingly attractive. Both countries have a lot in common in terms of their way of clothing; they consider the same importance for functionality, efficiency and beauty at the same time. I think that the difference comes from Afghanistan’s convulsive and tense atmosphere, so people have to confront the situation with more persistence to get what they want and achieve their dreams. They will never give up on their dreams though.

The location is striking.

We used an under-construction building as our location because it’s where Afghans mostly go to get a temporary job, it’s where they spend most of their time. And, to us, it was a symbol of the creative process. But this time it was different; The under-construction building became the place they came back not to work but to shine.