I grew up in paradise — or so I have been told. My family emigrated to O’ahu, Hawai’i, from the Philippines when I was nine years old. Swapping one set of islands for another, I only had the vaguest idea of what life in Hawai’i would be like: palm trees and white sand beaches, turtles and pineapples. In short, everything I knew about my new home was a stereotype, my perceptions as flat and one dimensional as the postcards that advertised Hawai’i to the world.

Upon arriving, I quickly realised that Hawai’i was more complex than the exotic paradise it’s painted as to outsiders. Yes, there were stretches of glittering beaches and verdant mountain ranges — all the natural wonders that the islands are famous for. But for many locals, that is where the fantasy ends.

“People’s perceptions of Hawai’i is grass huts and sandy beaches,” says Kawika Pegram, a 19-year-old activist organiser. “But we forget that there are real communities here, real people that live and work here, that struggle to make ends meet.” Kawika, who was born in Hawai’i, recalls a childhood defined by economic strife. His mother raised the family on her own, at times surviving off food stamps. And yet, she was making $12 an hour, just slightly above Hawai’i’s minimum wage. “Even living above minimum wage as a full-time worker, it’s really hard to support yourself, let alone support another person or a child. Growing up, it’s way harder than it needs to be.”

That’s because Hawai’i has the highest cost of living in America. Decades of being billed as a luxury destination have made affording life on the islands nearly impossible. Earning $67,700 a year in 2021 is considered low-income in the urban core that is Honolulu. Many locals hold down multiple jobs just to afford rent and other basic necessities.

Growing up, my mom worked until the twilight hours at her job in the service industry while my dad consistently filed overtime at his construction firm. Every other year, we would migrate to a new home, sharing rental units with extended family members to cut down on cost.

In Hawai’i, living in a multigenerational home is not uncommon, especially as it’s one of the most sought after real estate markets in the world. Early this year, the median price of a home on O’ahu reached a record high: $1 million. So, it’s no wonder that our state sports the second-highest rate of homelessness per capita in the nation, second only to New York.

And yet, popular perception continues to see the islands as a paradisiacal wonderland, where life runs languidly on island time, and the cares of real life are discarded once we arrive at Hawai’i’s Edenic shores. “It’s a fallacy of paradise,” says Kawika. “By and large, it is the biggest misconception, and the most dangerous one, when it comes to the outside perspective of Hawai’i.”

As I grew up, more and more of the paradise fallacy was unravelled. I learned of the legacies of colonisation that continue to plague the islands: how Hawai’i was once a sovereign nation until capitalistic greed led American businessmen to mount an illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy; how sugar and pineapple barons cultivated a caste system amongst the migrant plantation workers that toiled at their fields; how extractive colonialism continues to this day with the tourist industry.

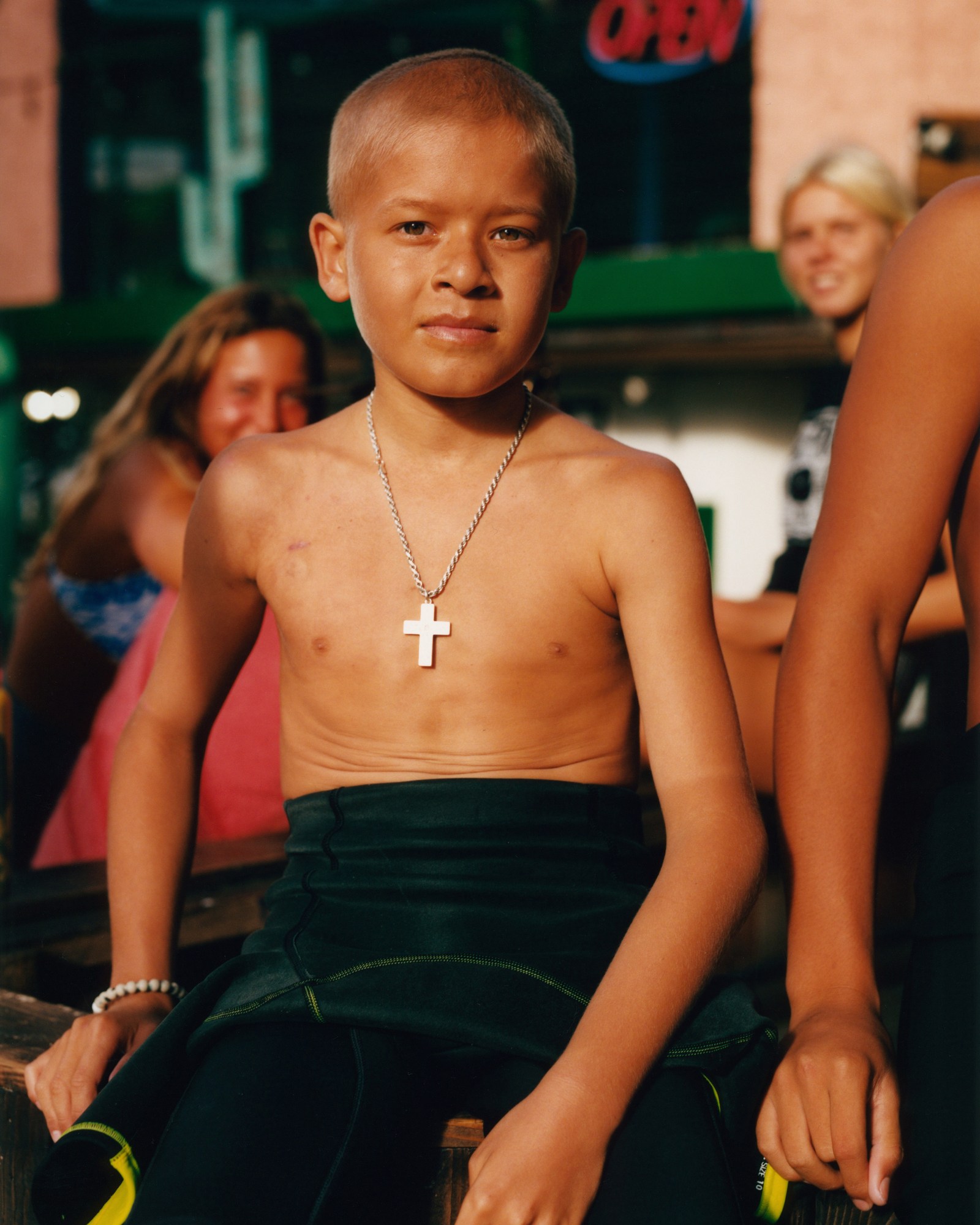

To grow up in Hawai’i means to live with a contradiction: that your home is a paradise, even as the past and present prove otherwise. This wrestling with identity is at the heart of photographer Maxime La‘s latest project. Shot across O’ahu, Hawai’i’s most populous and developed island, the street-cast photos featured within Hawaiian Youths hope to capture a facet of real Hawai’i.

“I realised as I was getting into Hawai’i, that there was something really interesting and almost delicate about the identity that’s happening on the islands,” Maxime explains over Zoom from his home in Paris. He first came to the islands in early 2020 to tend to his recently deceased father’s affairs, who had spent his last years in Hawai’i. In between organising his father’s possessions, Maxime was immediately struck by how vastly the island differed from what he previously imagined.

After he returned to Paris, he felt the compulsion to return, to digest these newfound revelations and experiences through his favoured medium: photography. “This project seeks to document the youth of Hawai’i, and present a series of portraits of its future generation that steps outside the postcard stereotypes,” he writes in the project statement for the series.

By turning away from these postcard stereotypes, Maxime is able to focus his lens on the realities of island living. Hawai’i’s famous landscape is never the focal point, and many of the portraits are shot against the islands’ rarely seen urban backdrop. For Maxime, the project was not about perpetuating yet another tourist fantasy. In capturing the myriad of young faces, which span a variety of ages and ethnicities, he aims to convey the complicated experience of coming of age in a place that so many deem as paradise.

Take, for example, Brandon Santos, who goes by the pronouns they/them, a subject of one of Maxime’s photographs. In their portrait for Hawaiian Youths, the 22-year-old Brandon poses in front of a 7-Eleven convenience store with the popular Japanese drink, Calpico, in hand. With their platinum blonde fringe and grunge-inspired aesthetic, they are a far cry from the beach babe cliché most associate with the islands. And yet, Brandon has experienced a life that is quintessentially Hawai’i: battling rising rent prices and struggling with the high cost of living.

“All anyone sees Hawai’i as is a little vacuum-sealed paradise, where nothing goes wrong, and all the locals are just here to just serve you aloha spirit on a fucking plate,” they say. “It’s not a paradise to be here. It’s a struggle every day to get by.”

Three years ago, their mother remarried and moved to South Carolina. Brandon decided to stay in Hawai’i. As a kanaka maoli or Native Hawaiian, Hawai’i is the only home they have ever known. “I’m not a beach person or a hikes person — all of the stereotypical things that make people enjoy living here,” they say. “The only thing I can really grasp is my family is from here. So, even if that means living paycheck to paycheck, I am fine with that.”

But not everyone is as strong-willed as Brandon. Each year, more and more locals and Native Hawaiians move off the islands, no longer able to afford the price of their home. In their stead come billionaires like Mark Zuckerberg, who gobble up Hawai’i’s finite land. Even for the younger generation, the viability of remaining in Hawai’i already feels out of reach.

“That’s one of the main reasons why students are told to go to college or live the rest of our lives somewhere else,” says 16-year-old Ember Isabello. “I don’t think I could live comfortably here because the cost of living is so high and pay is so low. I don’t know how my parents do it.”

And with tourism as the state’s primary source of income, every industry seems linked to servicing the commodification of the islands, leaving Hawai’i’s youth with a paltry selection of potential careers. “It’s like the brain drain of Hawai’i,” says 16-year-old Allena Villanueva. “I don’t think there are that many opportunities here to make a career.”

Most recently, the resurgence of tourism amid a deadly pandemic has caused further strife for locals, who endured months of strict lockdown only to see crowds of tourists flocking to the beaches half a year later. “It’s just been really hard having to be in my home, the only place I would call home, and walk outside and see it be disrespected,” Brandon says. Social media posts of tourists assaulting endangered Hawaiian wildlife and gathering maskless in crowds have galvanised locals, many of them Hawai’i youth who are now becoming more politically active as a result.

“Those who come here to experience this pleasure emporium are feeding the machine of US colonialism that is oppressing and killing us,” says Kainoa Azama, a 19-year-old kanaka maoli activist. “Hawaiʻi’s largest industries, tourism and militarism, have coined our lands as ‘paradise’, asserting themselves as having domain over these lands and the ability to pimp out our land and people, despite the international recognition of the illegal occupation of our islands.”

With this emerging activism among Hawai’i’s youths, Kawika sees a potential for a different Hawai’i, one that is no longer defined by the idea of our home as paradise. “If we’re not fighting for what we deem necessary to make Hawai’i livable and we’re leaving, we’re abandoning Hawai’i,” he says. “It’s important that, if we can, [we] fight to stay and make it so that other people can stay too.”

In one of the most poignant images in Hawaiian Youths, two local kids stand on the precipice of a stone pier. Beyond them, turquoise waves lap up against the shore, and beachgoers dot the horizon. It’s a typical day in Hawai’i nei. Yet Maxime’s framing paints the kids as something more symbolic, perhaps even prophetic. Are they on the verge of jumping, pushed off the islands like so many locals before them? Or are they sentinels at the border, Hawai’i’s next generation standing guard to protect the only home they’ve ever known?

‘Hapa’, a solo exhibition by Maxime La, is on view at 7 Rue Saint Claude, 75003 Paris between September 21-25th, 2021

Credits

All images courtesy Maxime La