In the 1980s in Spain, cultural rebirth and freedom of expression burgeoned after decades of political dictatorship under Francisco Franco. This exuberant and brut energy crystallized in a countercultural movement dubbed La Movida, embodied by concert-goers and party hounds. The exhibition La Movida: A Chronicle Of Turmoil, 1978-1988 (on view through September 22 at the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in the south of France) juxtaposes the work of four Spanish photographers who depicted this centrifugal force, headquartered in Madrid but that trickled out to other cities. An emancipated and punk spontaneity fueled this new generation, enthralled by music, fashion, cinema (…young Pedro Almodovar was a key La Movida figure), and all kinds of visual culture.

The June 6, 1985 edition of Rolling Stone included the feature “Youth Reigns in Spain,” (Julian Lennon was on the magazine’s cover, wedged between headlines like “Prince Goes Psychedelic” and “Amy Grant’s Christian Rock”). The piece examined the cultural punch of La Movida, paired with photos by Mary Ellen Mark. In this post-Franco era, young people “declared open season on all Spanish institutions: God, the Catholic church, the army, sex, the family and the old right,” the article declared. And yet: “Madrileños… they’re not purposely trying to make a political statement. Instead, they’re telling the stories of their lives, which were shaped in a political arena.”

The four artists presented in the show—Alberto García-Alix (b. 1956), Ouka Leele (b. 1957), Pablo Pérez-Minguez (1946-2012), Miguel Trillo (b. 1953)—were intrinsic to the movement not only as participants but as chroniclers with unique takes. Miguel Trillo’s street style images documented a wayward and stylish generation, while still subtly influenced by classical portraitists like August Sander, Diane Arbus, and Irving Penn. Trillo discussed the pleasures of the photocopy, the weight of ideological fatigue, and how he stayed observant amidst the nightlife mêlée.

You improvised your photographs on-site: in the street, at clubs and concert-halls… Did you ever consider having a studio?

My backgrounds on-site were improvised, yes, but thoughtful. Sometimes I’d choose the wall first, and then hope someone would pass directly by it or walk nearby. I had the patience of a fisherman, waiting for something to bite.

How important was it to build a rapport with your subject?

I never liked stolen photos. I talked to people and made them pose naturally, though I would purposefully put them against that wall or have them sit down. Sometimes unexpected things could happen. Everything had to be very fast: one or two photos at most. I tried not to make them smile like the fashion magazines and advertisements did, where young people always were always flashing their teeth, always ‘happy.’

In the show, you talk about the disparity between your photographic practice and the way fine art photography—and even the press—regarded photography during this era. Can you elaborate on this?

In Europe at the time, my generation wanted to consider photography as an art, not just a profession. We wanted to be exhibited in contemporary art galleries rather than in bars, or even exclusively in photo galleries. In the early ‘80s, I managed to exhibit in two important contemporary art galleries in Madrid. I wanted to break with the usual framed black-and-white photos behind glass, displayed as if they were drawings or engravings. I didn’t like framed photos. The only ‘traditional gesture’ I made was signing, numbering and limiting the edition of my images, to facilitate sales and collecting, even though they were often photocopies or color photos. I projected color slides. And true, I didn’t like the way photography was treated in the press either, so I decided to publish my black-and-white photos in fanzines and artist books that I edited myself . In the ‘90s, photography was very present and ‘normalized’ at contemporary art fairs; at the turn of the century, with the Internet, so many new paths have opened up.

That experimentation in form—projections, fanzines, photocopies—was a renewed visual language. Did this format make you reconsider your subjects? Or your viewers?

A slide projector, a fanzine, or color photocopies were all more relatable to the viewer. It was a matter of style.

You took photos in London at the 100 Club that showcase a similar style and vibe to the Madrid scene. For you, what resonated between the scenes in different cities internationally—and what was specific to Madrid?

Madrid was specific in that we were the very first wave: everything was new and all mixed up, we were kind of avant-garde, kind of precursors. In London, there was already a huge industry of music, fashion, clubs, festivals, magazines. The difference was enormous, although we shared the same enthusiasm. I returned to Madrid from my London vacation with photos, as well as with magazines like the first iterations of i-D and The Face. In Madrid, hardly anyone had dyed hair or tattoos, yet there was already a resemblance to London or New York with a blatant sex-and-drugs lifestyle.

Do you think something can be said about the specific generation and the era during which these photos were taken? If so, what anchors them in this specific historical window?

When a city—a country—and a young generation encounters freedoms that their parents or even older siblings did not have access to, it produces a fresh energy. That was La Movida: an epoch that, besides being a lot of fun, spurred a lot of artistic activity.

The exhibition text describes your work as a kind of “map” of tribes (punks, mods, rockers, teddy boys, heavies, etc.)… Do you see yourself as a kind of social anthropologist? Or do you see yourself as more of a street style photographer?

Yeah, I guess I see myself as a street style photographer. I like the street, the chance encounters; there is no intention to ‘study’ anyone in my photos. Rather, it’s about going to have fun and looking, going where the scene is: concerts, festivals, fashion weeks, commercial streets.

Today, there is a lot of rethinking pertaining to gender norms. The style at the time you were photographing showcases a lot of gender-bending aesthetics. What was your sense of how gender was expressed then?

There were quite a few strong female figures, and quite a few gay men who were part of La Movida, but there was no feminist or gay pride discourse. Everything was at the level of the visible; nothing was organized. We came from a time defined by an excess of political discourse, of militancy, of rules. There was no interest in decrees or slogans after that.

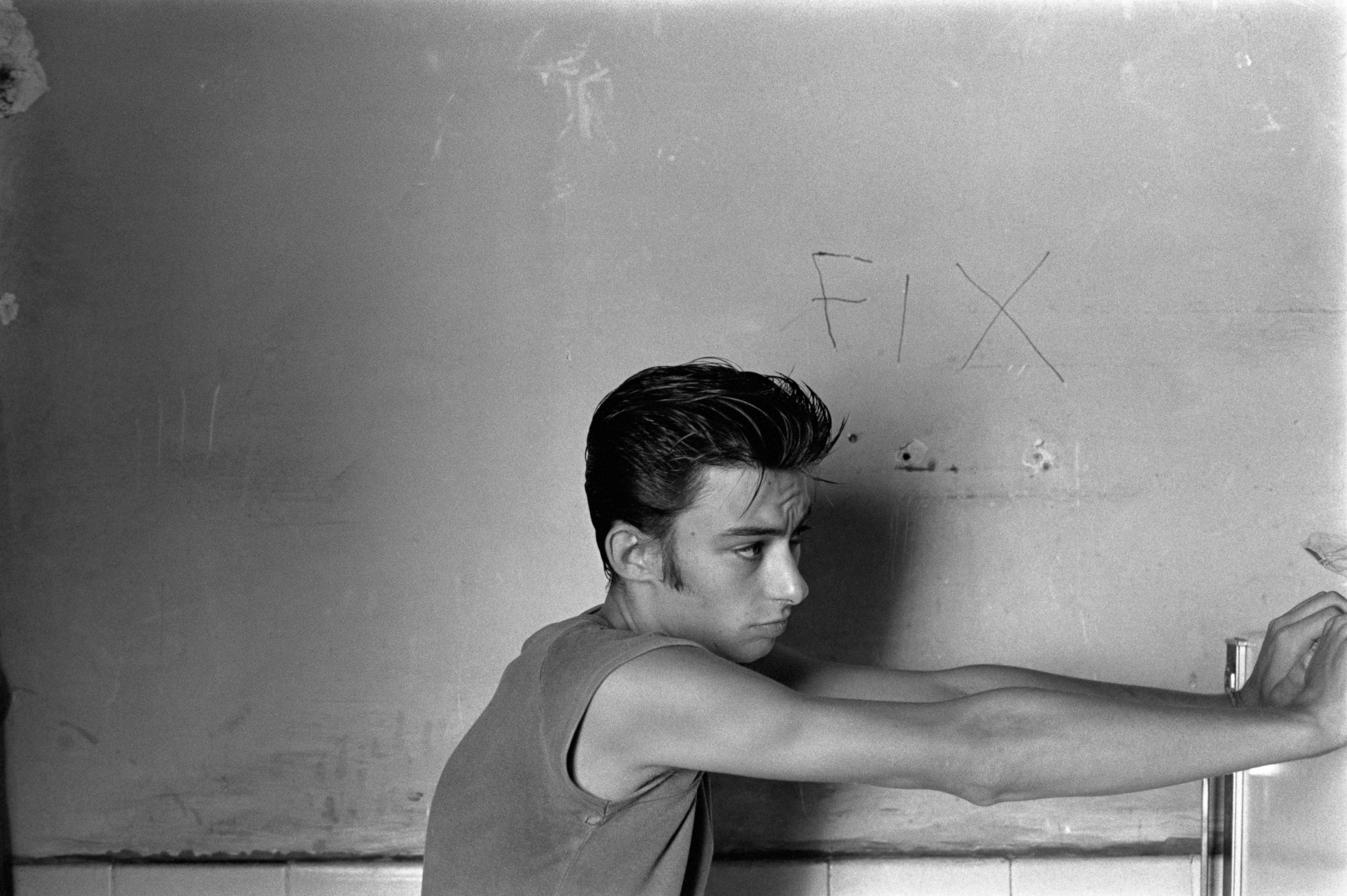

The Alberto Garcia-Alix photos in the exhibition overtly reference drugs and addiction. How much did that aspect of the scene seep into what you covered, even if less obvious in its depiction?

In many pictures from La Movida, there are traces of alcohol, amphetamines, hashish, acid, heroin… In my photos, you don’t see them, but you assume their presence. Some subjects died months later: from accidents, AIDS, overdoses. It was all a result of the desire to experience risk, to feel frenzy. The substances had an intellectual prestige. In the world of art and music, there are no controls on alcohol or drugs when creatives are onstage or in their studio.

What was your relationship to other three photographers in the show? Were you friends, competitors, neither? Was there a sense of community?

There was a sense of community, because there was a reduced circuit of clubs and clothing stores. And on Sundays, in the wee hours of the morning, everyone went to El Rastro. We were not friends… I was the only one of the four who had not been born in Madrid; I went there for college. We knew each other by sight, but we took very different pictures. We didn’t compete. Alberto Garcia-Alix and Ouka Leele never went out at night to concerts or parties with their cameras. Most of Pérez Mínguez’s photos were in his studio. They wanted to live off photography professionally. I was neither commissioned nor did I want to be a professional. I worked as a literature teacher in a public high school. Photography was for my free time, my moments of fiction.

What is your photography practice like today?

I haven’t changed at all. The difference is that now, after 35 years of teaching, I have retired as a teacher of literature. Being older, I take more photos by day than by night. What interests me most are manga festivals, fashion weeks, commercial shopping streets. These are my hunting grounds. Like I said: I have the patience of a fisherman, but with a camera instead of a fishing rod.