After being diagnosed as HIV positive, Pierre-Alexandre Fillaire had to choose between giving in to self-destruction or grabbing the bull by its horns and charging ahead.

This wasn’t an Eat, Pray, Love situation. In this predicament, finding meaning was a matter of survival. He decided to start anew and pour all of his energy into creating images through styling. A process that, though radical, he took step by step, one day at a time.

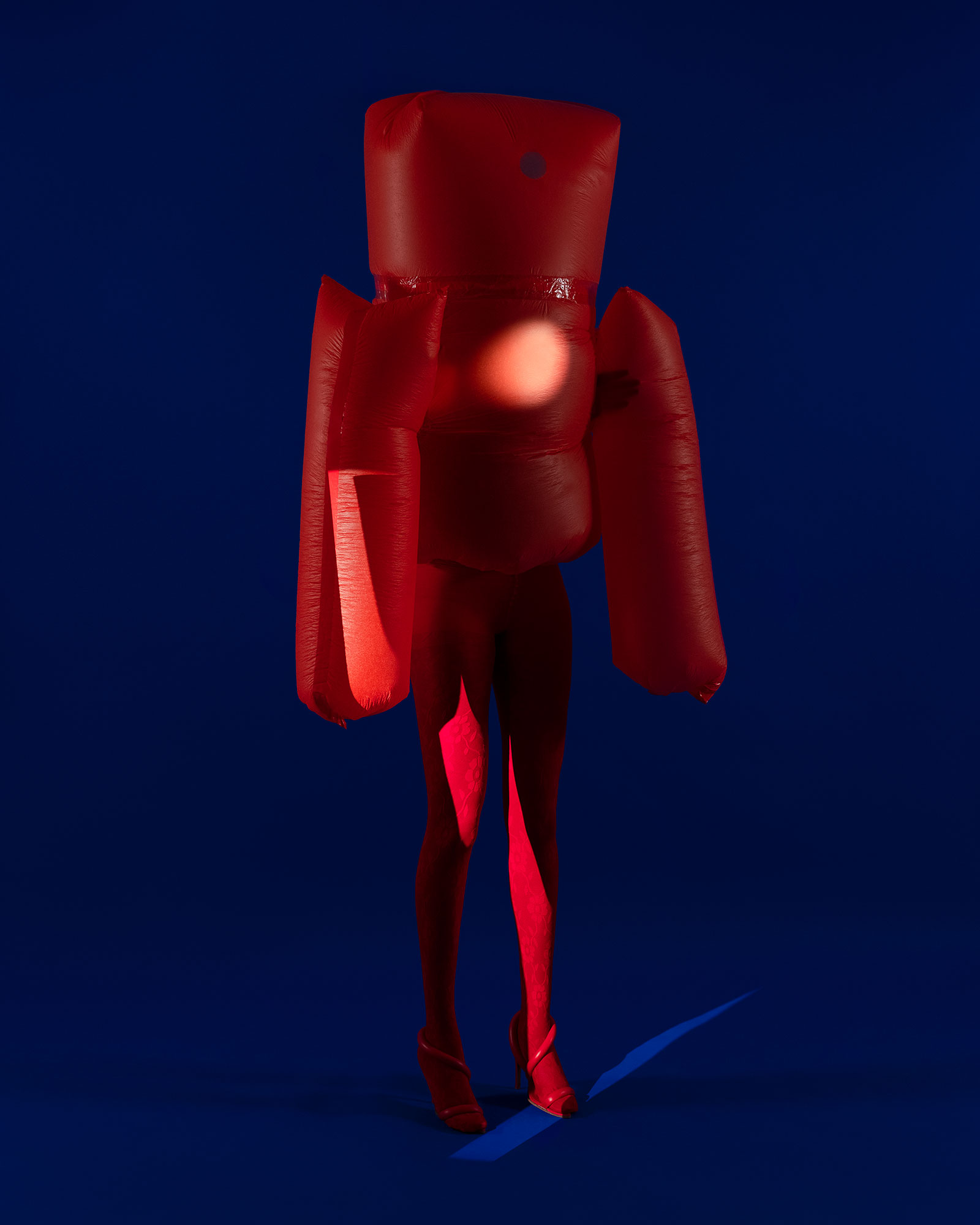

Utilising clothing as a medium, he could almost be better described as a sculptor, costume designer and, at times, installation artist. Pierre-Alexandre pushes the boundaries of identity and absence. As he puts it, “I tend to go further by expanding truth through a performative approach of reality. Reality is only what we perceive of what is happening.”

His works reinforce the idea of connectedness. “I care about the environment a lot, in terms of what brands I use, and in terms of the image itself,” he says. “Global warming is my main priority. And to fight it, we need to fight all social injustice such as racism and gender inequality. So it’s all very much connected.”

In 2014 you moved from France to London. How would you describe that first year in the UK?

While I was applying for my master’s in curation and art criticism, I was also coming to the end of a relationship, so to be responsible, I went for a check-up and discovered I was HIV positive. It came a bit out of the blue, really, but also as a life-changing experience.

I was not quite prepared. It made me lose all ownership of my body. Back then, it felt there were more prejudices about HIV. But the truth is that it can happen to anyone, and I had to figure out a way to trust people again after that.

In the past, you’ve said, “we all have an expiration date”. Could you elaborate on that thought?

I have been depressed from a very early age. And my HIV diagnosis was recognising death as an entity. One day or another, I was going to die. It is inevitable. But encountering such emotions made me realise how lucky I was to be alive and how important it is to take upon the challenges of life before it ends. Life needs to be taken slowly, one day at a time. If you respect yourself enough and allow some trust in your own self, it is possible to keep on going day by day. We all have an expiration date; let’s delay it as much as possible.

What was the process between finding out and deciding to be openly HIV positive?

HIV switched my perspective on people in general. I will always remember how a workmate once compared a skinny guy with someone dying from AIDS. Such comments build fear and insecurity in someone. Back then, I made two promises to myself: To keep up being alive and to work hard enough to one day be able to share my story, hoping it would help people with their own mental and body issues.

In 2016, I started to meet a more open-minded crowd. I discovered styling that same year and right away decided on making it a life goal. I knew I could take risks through styling.

At first, my work was quite dark. I wanted to hide the subject to alienate the human condition. The principles behind this were protection and concealing identity. It was all very much a reference to my HIV experience.

In 2019 you got the nomination for the New Wave: Creatives from the British Fashion Awards.

I was in Japan when I found out. It put me in a sort of trance. For me, it appeared as an opportunity to come out on a huge platform to say, “I have HIV, and it’s OK. You can make it too.” When they released my story on my bio, I was owning my body and mind to a whole other level, and I am certainly freer now because of it.

Absolutely. When you feel that you cannot share parts of yourself, you become a prisoner of your own body.

Yes. But listen. You also don’t owe anybody your life story. It should be your choice to share it or not. But owning your own body and mind is something that is extremely important whatever path it takes you to.

After that big break in London, what motivated you to move back to France in 2020?

The next big step of my life was to work on my wellbeing via sobriety to keep up with “mens sana in corpore sano“. Covid was a perfect time to move to the countryside before finding my footing in Paris.

Now I feel in a position where it’s not about finding myself anymore but about being a stylist. I’m much happier to show people’s faces in my work now, even though I still have some projects where I build myself as a creature around topics that I believe in.

So, is it yourself inside those “creature” costumes then?

Yes! It was a way to express my own annihilation and the contradiction of a presence within an absence. It helped me a lot to accept myself continuously and work on social anxiety. It becomes much more intimate and relatable while still taking oneself out of the equation. I have also started Butoh dancing to research my own body and expression.

In the last project you did in Ukraine with the brand Commun’s, there’s portraiture of different people and real emotion.

I researched traditional Ukrainian wear. I had some books sent to me from Russia. The idea was to go to people’s homes and capture their beauty while keeping communication open between cultures. A big part of my work is to amplify people’s messages through styling and set design.

Take, for example, this pine cone hat that was put on Violetta, an art teacher living in a village called Biuchak, (a locality that did not have any visitors for over 15 years). When we met, she told me how she discovered this place 20 years ago and used to organise parties there. Her freedom and creativity were so inspiring. She was perfect for this specific headpiece. That was the process we followed for each subject in this project.

What was the reaction of the people once they saw themselves in the mirror wearing these attires?

They were like, “Oh yeah! This looks like the Ukrainian babushka.” They believed in us.

That must be so rewarding. They actually saw the work that you put into the research.

Sure. But the most rewarding [thing] was all that we learned. As from my HIV story, through this project, I have rediscovered that one cannot make assumptions [about] people. In order to know people, go and meet them. I don’t understand the concept of copying or taking inspiration but then being ashamed of where it comes from. Lots of brands do not acknowledge where their inspirations come from, while there is a lot more to learn by connecting with people directly and proudly working together and building regional pride.

As a stylist, you create a special bond with the people you dress. And I have also found that when you make yourself vulnerable, people open up with their own stories.

On that note, you have been invited to be the guest editor of a performing arts magazine. You started to work with celebrities for this, which is something I wouldn’t necessarily expect from you. Why did you decide to take on this project, and what is your approach to styling celebrities?

This opportunity came a bit out of the blue. It’s for a young publication that is trying to subvert the publishing format by donating 100% of their sales profits to charity, which is unheard of, especially when it involves celebrity and fashion. So the philosophy of the project attracted me a lot.

Still, it seems like an odd turn, given your body of work is so far from that.

In our day and age, we have enough resources and knowledge to be able to manage different targets. We are also evolving. And if, before, I had the need to focus on sculptural shapes, I now feel very much driven by styling people.

I find myself as deeply inspired by the styling of Run-DMC in their early years as I am by some obscure 16th-century French drawings and lithographs. What drives me is the authenticity and a unique sense of perception of reality. When it comes to styling celebrity, my favourite part is to look for independent designers that I know the celebrity will love and inevitably want to promote.

So is this your main project at the moment?

It is taking a lot of my time, but I am also working on consulting for clients, developing an ethnological archive book and preparing a big exhibition for this next fashion week in Paris. So look forward to that!

Credits

All images courtesy Pierre-Alexandre Fillaire