Back in 2011, Warsan Shire wrote, “No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark.” This was the year of the Arab Spring and the beginning of the Syrian Civil War. The then 23-year-old Kenyan-born Somali-British writer seemed to capture something of the paradoxical optimism and despair of the period. Quartz Africa called the poem from which the line was taken, “a rallying call for refugees and their advocates.” Beyoncé cited Warsan as an influence on her 2016 album Lemonade, quoting her work extensively in its accompanying film. Warsan’s art seemed to penetrate the mainstream, and her characteristic melding of photojournalistic imagery with familial strife and multilingual lyricism embodied the predicament of asylum seekers in a way that seemed difficult to surpass.

Then there was an explosion. In 2016 the UK voted to leave the EU. The US elected a reality TV billionaire with extreme views into the Oval Office. This coincided with a rise in the far right, who — emboldened by increasingly fascistic rhetoric in the American and British press — began to capitalise on their political moment. In the four years since, this has shown little sign of abating, but, like the vanguard led by W.H. Auden, Louis MacNeice, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis in the 1930s, politically engaged poets with progressive views are fighting back and younger readers are paying attention.

As of last year, there has been a record 12% increase in the overall book sales of poetry titles in the UK. Two thirds of readers are under 34 and over 40% are between the ages of 13 and 22, with teenage girls and young women identified as the largest consumer demographic. Poetry is more popular than ever.

The 2019 General Election was a dumpster fire and the prospect of a left government in the UK looks as distant as ever. However, as Warsan Shire’s work proves, art provides hope and the possibility of redemption in times of despair. A plethora of new poets have taken up this mantle in the wake of the UK’s continued descent into demagoguery, and are providing a blueprint for how we might find our way out.

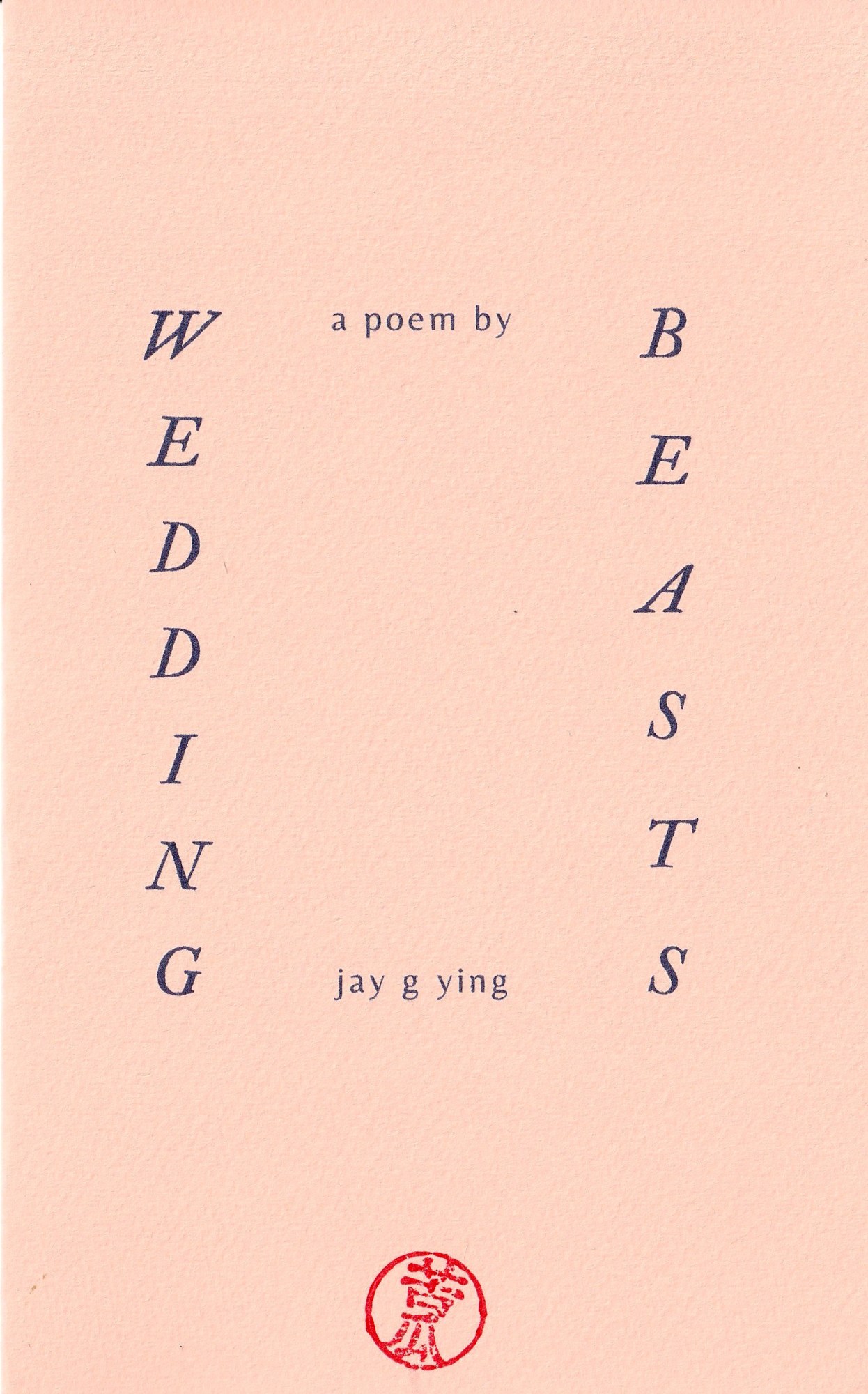

In 2019, Chinese-Scottish poet, fiction writer, critic and translator Jay G. Ying published his debut pamphlet Wedding Beasts, a book in the form of a long poem which explores the complex interactions between tradition, queer desire and worship, often in formally challenging ways. His follow-up Katabasis (meaning ‘descent’ or ‘the sinking of the sun’) due out later this year, links the ancient Sumerian epic The Descent of Inanna to contemporary neo-colonial violences as a consequence of military occupation.

“My writing is preoccupied with our nation’s external limbs,” Jay says. “The political [should] burst out of the poem fully-armed like Athena leaping from Zeus’s head than gaze at a poet’s head turned too far inwards.” Jay is, however, cautious. “I do worry about how the publishing industry may cannibalise a few select minority writers and present them as ‘urgent’ and ‘unflinching’ truth-tellers… I have no interest in proving my humanity for those who see nothing beyond my skin.”

Similarly, Momtaza Mehri’s pamphlet Doing the Most with the Least, published in 2019, explores the complex intersections between the personal and geopolitical — especially in the lives of communities affected by movement and war. In 2018 she was appointed the Young People’s Laureate for London, and in February of this year she was awarded the Manchester Poetry Prize at just 26.

“Violence often depoliticises and debilitates the most vulnerable,” says Momtaza. “Poetry is one energising tool we can use against this heavy cloud of social fatigue. That’s what I am thinking and writing towards… I try to ground myself amidst this acceleration by prioritising reflection and care in my work.”

Like Jay, Momtaza is also proceeding cautiously, keen not to elevate herself above the experiences of those whose experiences inform her work: “I try to resist the notion of ‘responsibility’ since it reinforces the pedestalised role of the ‘poet’ or artist within society as a uniquely insightful witness, providing commentary from a comfortable distance. We’re all responsible. We all have to confront the truths we deny in ourselves, our communities, our societies.”

Another young poet pushing forward with this is Phoebe Stuckes, a four-time winner of the Foyle Young Poet of the Year Award and recipient of an Eric Gregory Award last year. Phoebe, who is about to release her first book, Platinum Blonde, writes quietly unsettling poems about everything from gender stereotypes to explorations of selfhood in the age of hyperinformation.

“I mainly feel angry,” Phoebe says. “I’m angry for myself, for my friends, for everyone who is less fortunate than I am. And then I get really fucking tired. I pass between those two states permanently, until, I assume, I will at some point spontaneously combust. So there is a lot of rage in my poems.”

She continues: “I think truth is mostly personal, but I also think to avoid engaging with politics or to declare that your work is apolitical is to risk upholding the status quo. I write a lot of love poems and a lot of weird poems, but because I’m female and queer these are read as a statement on femaleness and queerness.”

These poets and their writing are a cause for hope and celebration, though they are not the only ones. This year’s T.S. Eliot Award shortlist included several challenging political entries. Jay Bernard’s Surge, for example, traces the injustices towards Black Britons that followed the New Cross Fire of 1981, otherwise known as the ‘New Cross Massacre’, to Grenfell, and looks to the possibility of salvation in the form of reggae and dancehall music, community work, family, and of course, poetry.

This year’s T.S. Eliot winner, A Portable Paradise by Roger Robinson, removed the families caught up in the Grenfell fire from the mainstream media narrative of victimhood, and turn them into something altogether more magical and compassionate: real people living real lives. That such a thing seems radical in 2020 is an indictment of just how low the establishment narrative has stooped, but as Momtaza Mehri points out: “Poets can use our medium to illuminate and write into these gaps.”