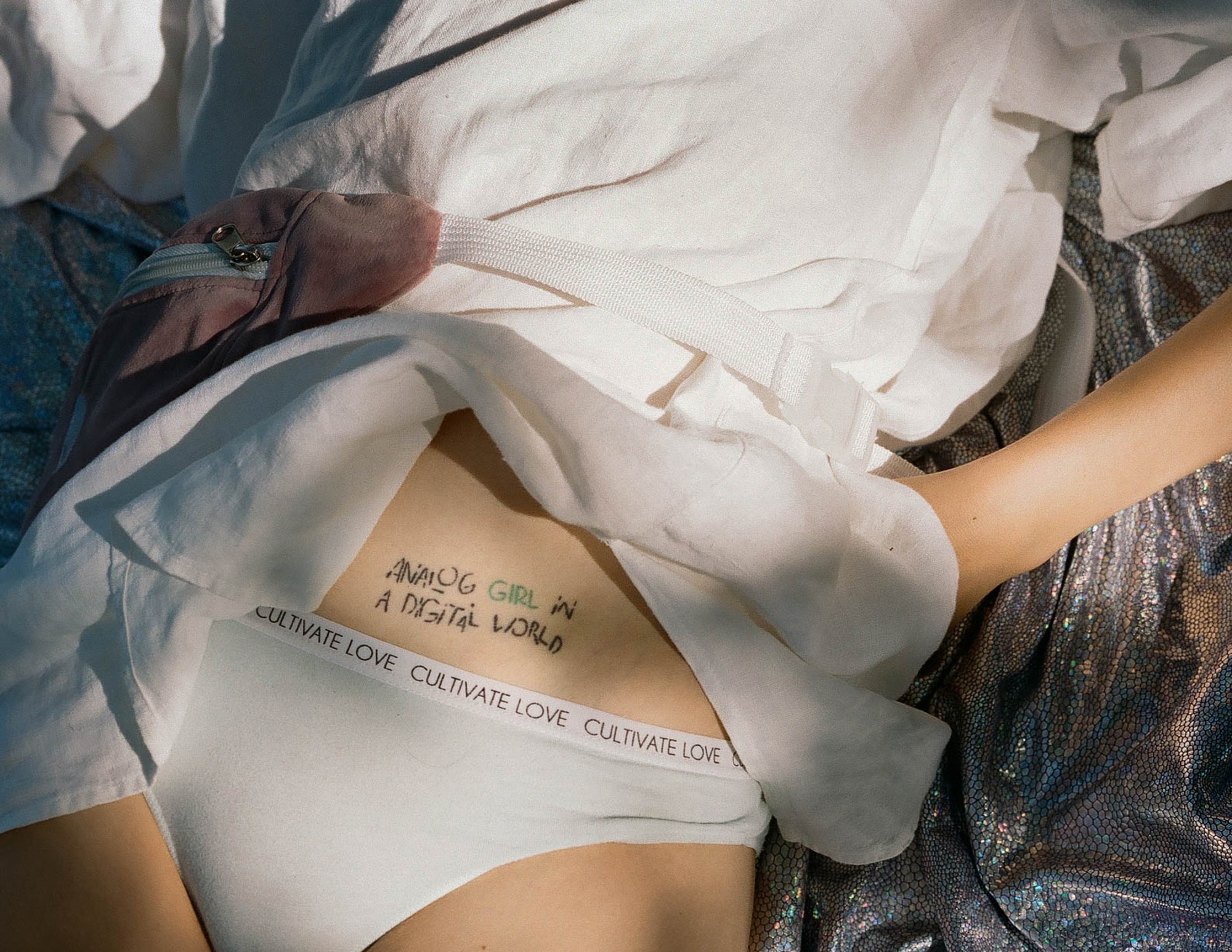

Ira Lupu grew up taking pictures in her native Ukraine, but it wasn’t until 2015, when war and military conflict broke out in her country, that she became invested in photography as a way to express what words couldn’t. Ira went on to work as a local art stories producer for Ukrainian-American photographer Yelena Yemchuk, while studying at the ICP in New York. It was there, that she developed “On Dreams and Screens”, an aesthetically and emotionally powerful multimedia project exploring female sexuality and identity, both online and off. Ira’s series investigates various forms of intimacy within the life of a cam girl: what her reality looks like when she’s not performing, and how the virtual gaze seeps into her day-to-day existence.

Eastern Europe is one of the biggest hubs of web models, and Ira wanted to both demystify sex work in her native country, and provide a more nuanced portrait of her roots. Navigating consent and privacy with careful attention, she worked with six Ukrainian (and Ukrainian-American) cam girls in their twenties to highlight their various experiences, and celebrate them beyond fantasies or clichés. The project started in 2019, but when the pandemic hit, it became more emphatically about bridging inner and outer worlds — something that cam girls have long grappled with, and a challenge we now all face daily in our increasingly virtual lives.

We spoke with Ira by phone about the ‘new normal’ of long-distance relationships, filtering the self through digital platforms and rethinking the image of the Eastern European woman altogether.

“On Dreams and Screens” became a project while you were at ICP, but the idea started earlier, when one of the girls included contacted you for something else entirely…

Marina was the first girl I was introduced to; we met in Ukraine. She hired me, through common friends, to take pictures for an album she’d just self-recorded. All the tracks were inspired by her camming experience, and she wanted this particular look. This was the first time I ever met someone who was camming, who was a sex worker. I was struck by her openness, especially in a country that is still quite conservative — camming is illegal in Ukraine. I started meeting other girls, learning about them and how interesting and complex this world is for any type of online sex work.

How did the project crystallise?

The impeachment conversation was happening in the US [in early 2020]. Since Ukraine was involved, everyone was interested in my origins and asking me questions. The understanding of my part of the world is so limited that I decided I had to do something related to my home country.

I was thinking a lot about a 2017 Foam Paul Huf Award-winning project called “Ekaterina”, by Swiss photographer Romain Mader. It was a mockumentary about Eastern European sex workers. I remember when I saw this project for the first time, I was outraged by it — and so were a lot of other Eastern European women. There was even a letter that a lot of people signed about the project looking down on and objectifying the Eastern European woman. One of the heads of the jury was a well-respected critic, who has discussed who has the right to take whose picture, so I was surprised he didn’t consider this problematic! This kept me thinking about what it feels like to be an Eastern European female, and facing the misunderstandings of that.

How much did the subjects’ input influence how you presented them?

My approach was so collaborative that I broke the journalistic rule that you can’t get close to your subjects. I totally became friends with them. Just before talking with you, I had a conversation with one of the girls; we’re checking up on each other all the time. This question of agency over how a person is portrayed was very important to me — I would always talk to them about that. The “typical” image of an online sex worker in front of a camera… it’s not what the project is about. I wanted to learn who they are as people. By the end, I got maybe even a little too deep into inner worlds; I would almost dissolve into them. Learning what it’s like to be in someone else’s skin — this experiential element is important to the project. Not observation, but immersion.

As image-makers, I believe we have to bring this agency back to the people we photograph. We should constantly check in on ourselves, right? One of the mentors of my project was always assigning interactive portraits. You would photograph a person, show it to the person and then ask, “Is this really you?” And the answers you get are striking. People wouldn’t really connect with the pictures and the way they’re portrayed. So, I felt this responsibility to portray the girls and think about the final outcome.

Given the word ‘dreams’ in the title, how did you play with perception or even illusion?

The nature of the work that cam girls do is highly performative. What I’ve learned is that this work makes them very conscious — you see yourself on the screen all the time, you develop this interesting mental split between your image and your self — and I think the project touches on that. Also, what I’ve learned from working with performers is that people from such professions tend to develop an interesting relationship with the camera. My previous project was following a girl who works as a full-time model for six years, . Instead of trying to fight this consciousness, or tell them to just be natural, it’s interesting to proceed with how they function.

I really wanted to speak about this split — which is so relevant to us in lockdown, when we started to have this more intense virtual life — and learning about maintaining our own relationships at a distance.

The series resonates differently in pandemic times when everyone is Extremely Online…

The project became more about the psychological state of being when Covid hit. A lot of people started telling me they relate to the project even more. Suddenly, the cam girls became the people who had this really broad expertise. I was interested in this liminal space between the virtual body and the physical body; it started growing in that direction as well.

Though it didn’t start as a Covid project, it’s still charged by this isolation and split between reality and visual communication. I think it will be interesting to look at this when we can breathe out again!

Definitely! Regardless of this uncanny context, what were the assumptions you wanted to change?

I held back from making ‘obvious’ pictures. I was surprised to learn how much of this work — and this is why I drifted away from the more sexual or pornographic elements — is about communication, genuine communication from clients who reach out to them. This world is really charged with this very human energy, even though it’s still transactional.

It’s powerful that both components coexist.

It is, and they do! The tricky part of my project is that it’s not making a clear statement about anything. The girl who brought me into this world, she told me she had so many positive things that camming brought to her life, like financial independence — because she came from a very underprivileged, poor background. It also helped her gain confidence and empowerment. On the other hand, it was destructive to her mental state, in that she became a complete loner. It was important to me to get girls with different types of experiences, especially since I’ve never done sex work myself. Some girls I met, but didn’t end up working with. The ones I selected shared an approach that was more dreamy and artistic. None were big OnlyFans stars; they would fall into the category of girls who did it more nonchalantly. It’s a process for them to learn about themselves. Some of the girls had more traumatic experiences, some more empowered.

Is there any image in particular that highlights this ambivalence of the camming experience, falling between empowering and problematic?

There is one picture on the tram of a girl in Kiev. She came into camming because she wanted to work on how she perceived her own body. Finances weren’t the issue. They were a good addition, but not more than that. This girl’s particular experience was of trying to fix or work on her relationship with men overall, and even though she found it an interesting experiment, and at first she thought she learned a lot, the longterm effects of camming felt more challenging for her. The person behind her in the picture is a stranger. It’s completely random, we were just riding the tram back from somewhere where we’d been taking pictures. But when I look at the picture now, I see this… ghost. The presence of something that isn’t really visible in your life. Some girls feared meeting clients in real life — even the most vocal and open girls. I think this picture really speaks to this.

What about demystifying clichés about Ukraine or the Eastern European region?

One instance I keep thinking about: I was in New York at a party five years ago, and I met this American woman who was a little drunk, so maybe she was a little more direct than she would usually be. And she’s like, ‘Oh you’re from Ukraine? I heard they’re all easy women’.

Ugh.

I was like ‘Uh…’ [laughs] This is what my process is all about — why are things like that? Why is this part of the world being looked at like this? In some ways, obviously, there are still a lot of issues in the country. It’s not as patriarchal as it used to be, and it’s not as bad as some other countries, but women still have work to do. In terms of the broader picture, I just looked at The New York Times’ Year in Pictures. It’s a global project, and I was surprised by just how underrepresented Eastern Europe was. They had just one photo of Belarusian protests this year. Big and intense events in those regions don’t earn much recognition in American media. I’d love people to — in general, not only about Ukraine — be more open to each other, ask more questions, try to learn, try to educate themselves. I would love all of us to be more attentive to each other.

“On Dreams and Screens” will debut at Rotterdam Photo Festival and be exhibited at the Tbilisi Photography & Multimedia Museum later this year.