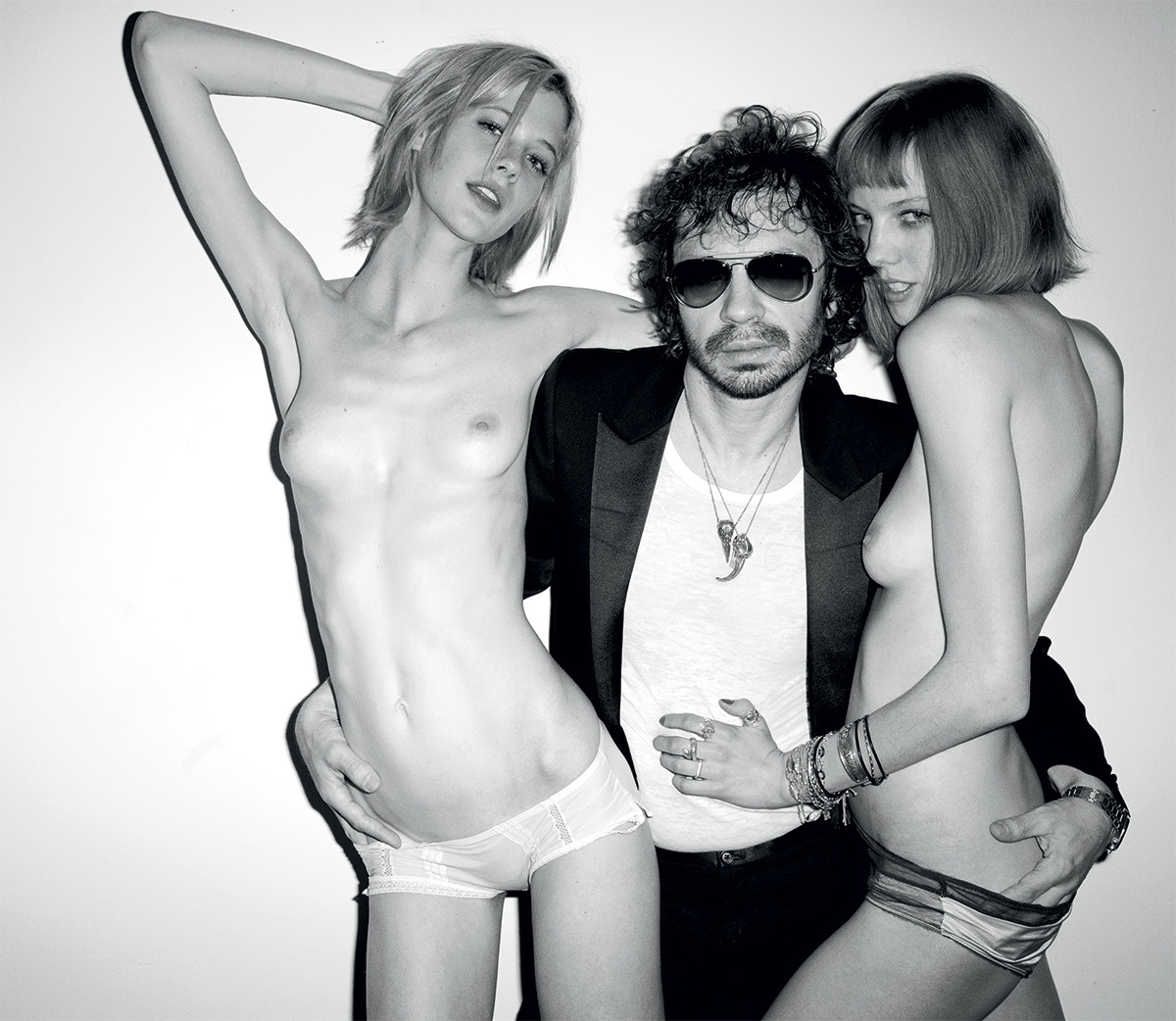

In the past few years, Purple Fashion Magazine has helped change the landscape within publishing by constantly pushing the envelope for counter-culture. Primarily set within the fashion capitals of Paris and New York, the magazine documents the miscreants, the marvelous, the creatives, the controversial, the beautiful, and the damned. Under Creative Director Olivier Zahm, Purple is never a second-hand re-telling of what someone on the outskirts deems as cool, this is firsthand experience seen through his aviator lenses because he always goes ball deep, up to his nuts in guts for his exploration of life, love, fashion, art, film, sex, and sexuality. His vision is an unflinching look at the steamier and sleazier side of life, where the Downtown New York art scene runs parallel to a chic French designer, next to some hot model, actress or girl about town in some fabulous state of undress, in Purple they are all as valid as one another. Because ultimately Purple is all about one thing, and one thing only – SEX, as Olivier openly admits, “To me everything is sexual in a way. Or, to me, let’s say that sex is the only thing that I really believe in. People keep lying about their sexual life, collective culture tries to keep it hidden, just because it’s the underlying truth behind everything — which makes it even more important today in the context of all of us no longer believing in anything.”

I sit in the café on the corner near the Purple office in Paris, waiting for OZ to arrive. He turns up late, his beautiful young daughter Asia running alongside him across the road, their motorbike helmets clutched firmly in his hand. He is instantly recognizable, dressed in his age-inappropriate uniform of Ray Ban shades, tight leather jacket, plaid shirt, Pamela Love talisman necklaces, too tight trousers, and Cuban heeled boots. He has purposefully carved an image for himself in the style of that other Parisian provocateur Serge Gainsbourg, and in the noughties transformed himself from faceless publisher into a publishing celebrity by projecting himself as the face of both Purple Fashion Magazine and Purple Diary which showcases his daily exploits. This was a conscious business decision made when Purple was facing difficult financial times and circumstances demanded reaction. “I changed my view, I changed my strategy, and decided to play the game: to be visible, to take pictures, to go to every party, to go to the fashion shows, to have meetings with clients, and to make money. I want Purple to survive after me, especially if I died in an accident tomorrow.”

We enter the Purple Institute and pictures of Serge Gainsbourg are pinned on the notice board next to Asia’s drawings and framed as the only art on display on the wall in his private office. This is a Saturday afternoon and Olivier’s Design Director Gianni Oprandi, his Fashion Editor Camille Bidault Waddington, and his Executive Editor Caroline Gaimari are all present and correct, discussing collections on Catwalking.com and designing layouts, respectively. Meanwhile, Asia’s new babysitter teaches her to paint in the next room. Zahm is both retro and modern, speaks in a soft, seductive French lilt, and is charming, charismatic, enigmatic, and an enigma. His appearance is craggy and brow beaten, his hairstyle is a permanent bed head, his eyes are googly, his demeanour a dated cliché, but there is something about his everything which harks back to a bygone era of rock stars, Hollywood, and supermodels that is oh so sexy and oh so right now. Zahm loves women, loves life, loves fashion, loves art, loves magazines, and loves, well, shagging. “Sex can be architecture, it can be a party, it can be an artist. To be inspired or attracted, I need to have this touch. To me, sex is the only thing that you can really sell. Sex connects people. It is something true. It’s a way to escape and sex is, of course, a source of inspiration.” We crack open a beer, Olivier lights a cigarette and we start to discuss how, where, and why he became the unlikely sex symbol and one of the people responsible for transforming Paris back into the chicest, sexiest city in the world right now.

A child of the 60s, OZ grew up during the 68 Paris riots where students demonstrated for equality, sexual liberation, and human rights — armed with philosophy, literature, and art as their weapon of choice. The revolution informed this young prince, who realized at a ripe age that a potent idea can, and later would, open many doors. His parents met on a beach in Portugal, where they were holidaying at the time with their respective best friends. His mother’s head was turned by his father driving around in a convertible white Mercedes and they started to double date, which tragically ended when the same car later crashed and killed his mother’s friend. His parents, still students, were living in the Cité Universitaire in Antony, which was a new residence for students and their families and a base for political and sociological ideas. The rooms there were designed by Charlotte Perriand and Jean Prouvé. This is where they brought up Olivier, his brother, and sister in the student quarters. Their home life was free, easy, and a happy time — filled with love, laughter, music, food, wine and, once again, sex. It was the 70s, the decade of free love and Zahm’s parents would frequent in the practice of group sex and partner swapping. It wasn’t seedy or salacious, just a way of life as normal as inviting friends ’round for a barbecue, except his Mom/Dad would leave proceedings with someone’s husband or wife, for days at a time. “My parents have a lot of lovers, they have a lot of affairs. They had group sex. At the time, my parents were really part of this alternative movement in Paris but quite bourgeois too. It wasn’t San Francisco or New York. It was the French way. They bought a farm 100 miles from Paris where they would invite friends for the weekend to have sex, to have fun, to dance. Teachers, doctors, a lot of journalists… My parents are still together; they lived a very free sexual life.” It was open and accepting and forged a strong sense of self within a young Olivier who firmly believes in the power of free love. He lived his formative years through the 70s, was a teenager in the 80s, and if he had been born during another time, would have surely held court in the Palace of Versailles, gambling, eating cakes and listening to Bow Wow Wow with Marie Antoinette, or chained up in the Bastille helping the Marquis De Sade pen The 120 Days of Sodom or some other filthy prose, unrestrained by morality or law. But this was France in the 70s, a time he remembers as soft, friendly, political, and very optimistic. “I remember long discussions between my father and all his friends talking all night long about politics, philosophy, and social issues. I have very good memories of my childhood.”

His parents started to spend most of their time at their farmhouse retreat, leaving a young Olivier to happily forge his own path in Paris. After the baccalauréat, Olivier went to preparatory school to be admitted into a state school, which is a place for higher education more rigorous than university. “I went to a state school that forms you to be the elite of the nation. You would end up being a university professor or a politician. I was attracted to going there because the students were more advanced and ambitious, especially in philosophy and literature, so I went there and made a lot of interesting friends. I studied literature and philosophy. It was a very intellectual context; I was very attracted to the mix of guys and girls, who could be the next Foucault or Deleuze. We were really ambitious and wanted to be writers, philosophers, or filmmakers.”

Around this time, at the beginning of the 80s, Francois Mitterrand of the Socialist Party was elected as the French President and OZ started to observe and take an interest in the art world. “I was 21 or 22 and I understood that contemporary art was a source of energy, a source of beauty, but also a continuation of the free spirit or the social critique that started to vanish during this new decade. Immediately I was attracted to art, more than fashion. I’d love fashion at night but I was not attracted to the professional scene, I was more attracted by the art scene. I started following the art world from fair to fair; I knew I wanted to work in magazines. I was just open to everything, I was making my own education and I was really impressed.” Olivier was curious, passionate, and talented, and soon met likeminded independent talents like curator and critic Nicola Bourriaud and his then girlfriend, the writer Elein Fleiss. “We were a little group of people in Paris who were really considering and fighting for contemporary art.” Olivier was charismatic and talented and was soon penning for the three leading art titles at the time and introduced a then unknown Jeff Koons, Martin Kippenberger, and Larry Clark to the European art world. Flying to America, Japan, through Europe, OZ realized he could feasibly set up his own operation and work to his own agenda, 24-7. “Freedom for me came from the art world because it was a place where I could meet the artists. I wanted to be a social critic. I was more interested in the category of intellectual, involving art and politics and writing sometimes. But I didn’t want to be a writer necessarily, I just wanted to be part of an intellectual world.” Through his writings he could connect directly with what was happening at the time, to experiment, deconstruct, and make a dialogue using his own life experience. “I was spending my time writing and traveling and then I decided to stop everything else and create a magazine with my girlfriend Elein Fleiss. I was attracted by everything creative and I wanted to be a part of it. Also, I knew I couldn’t just do any everyday job, I wanted to travel and meet people and really understand what culture is.”

It was the beginning of the 90s and the art world had become established, overground, commercial, and expensive in the wake of the ostentatious 80s. The fashion world became a caricature of ideas with exaggerated power dressing being the previous order of the day. It was OTT, fierce, bitchy, and cutthroat — all Dynasty, diamonds, and dollar bills. He witnessed firsthand the fashion world reach its most ostentatious conclusions with the implosion of the likes of Claude Montana and Thierry Mugler and with the economic crisis — just like today’s Credit Crunch — there was suddenly the opportunity for creativity and experimentation in an independent context. Olivier had to find a solution, voice, or message for his generation. In times of need, creativity comes to the fore and parallel to OZ and Elein’s feelings in Paris. Jefferson Hack and Rankin had similar notions in London and set up Dazed & Confused to document the shift in culture that was happening at the time. Harmony Korine was burning the American independent cinema rulebook with Gummo and Kids. Margiela was deconstructing fashion, grunge was the soundtrack of the decade, Marc Jacobs was fired from Perry Ellis and duly became Marc Jacobs, Chloe Sevigny and Kate Moss were the icons of the time, and artists like Corinne Day, Juergen Teller, Wolfgang Tillmans and Larry Clark were present to document all the exciting things goings on.

“That for us was the beginning of the 90s. It was a revolution and we could express who we were through art, through design, through photography, and through cinema. Everything made sense suddenly and it was all around us. We were the new generation and we were old enough to create our own show, to create our own magazine, and to try to express this difference. At the time, we strongly believed in the possibility of an independent culture that could be a creative alternative to capitalism. This implied a different vision of what art is and what it means to create an exhibition, a film, a concert.” Their idea was to envelope artists and to reject all theory, as they wanted Purple to be inclusive not exclusive even though their vision was uncompromising. “We wanted to give people direct access to what was new and emerging. It was important for us and for the people around us. it wasn’t just narcissistic or because we wanted to become famous or whatever. We did it with a lot of energy. We began to understand that fashion could be seen in an art context; it was a mix that was part of the magazine since the beginning. I just do it with the people around me, the people who interest me. I rarely force a contact.”

emerged as an interesting totem of the times which floundered during the latter half of the 90s. “At the end of the decade, a lot of magazines had emerged that were much more glamorous than . Elein and I didn’t know if we should stop and begin something new, but we wanted Purple to be a collective experience, not just our magazine. It was always about generosity and this alternative world. We believed that an independent culture could exist and survive and grow. But we understood around 2001 that the art scene was totally part of a global economy and that we couldn’t change it: every artist of our generation had gone solo, the independent scene and the collective spirit was gone and we didn’t know what we should do. Should we keep going or should we stop? Elein was convinced that we did an influential magazine for the nineties, and that we should disappear with the decade. She decided to go to live in Brazil and then Portugal, to have a child. I also decided to have a baby in 2004, but I didn’t want to stop Purple. I had to re-orient the magazine towards fashion and no longer anti-fashion.” So ten years on from it’s heyday, Olivier looked at the man in the mirror and decided to make a change. “I thought ‘ok, Olivier you have to lose weight, you have to become sexy, you have to go out, you have to go to every meeting and you go back into the night scene and you make things glamorous your way’. I know what glamour is — not this cheap sexiness — so let’s go again for the true glamour, let’s have Purple as the vehicle that I can enjoy and recognize as something interesting and make it valuable. I changed my look, I changed my life, and now we are in 2009 and the magazine is back on the scene.” Pick up any recent issue and find the :Purple Nude” portfolio photographed by Inez and Vinoodh, read Terry Richardson’s inspirational life story, marvel at Mario Sorrenti’s fashion, and immerse yourself in the accompanying Purple Book that showcases artists including Ari Marcopoulos, Harmony Korine, and the late, great, Dash Snow, helping to make the magazine more relevant and collectable than ever before.

Alongside the magazine, Olivier runs Purple Diary, his online blog, which showcases his old school glamorous lifestyle in black and white digital snapshots. Whether documenting his daughter Asia having her haircut at his favorite Japanese hairdresser, photographing the beautiful Natacha Ramsay wearing some fabulous Balenciaga creation, or Camille Bidault Waddington flashing her bare breasts, OZ has taken the basic scroll down blog format that Perez Hilton has claimed as his own and made it work for him. He realized the importance of spreading his message further afield via blogs or twitters, and most recently opened the Purple Boutique online store with a selection of products designed by friends, the first exclusive being The Purple Bag by Olympia Le-Tan, a chic collector’s item of the future. “Purple Diary is visited by 15,000 people everyday. The net is a new proposition for me, but something will come out of this contact, not commercially but I think creatively, I will have to move to follow new paths.” A fan of the Internet, OZ still believes in the power of printed matter, and just like the resurgence in vinyl over CDs, he believes in magazines because, well, he thinks they are sexy. “The internet sphere is amnesia: information arrives and disappears, arrives and disappears. Magazines always touch me because there shows a true love for the present time an historical trace of what’s going on by year or by decade. You can pick up an issue of Interview from 1974 and understand the 70s in New York, but you can’t figure out what 2007 was like by going to a website from 2007, because it has disappeared. I know there is love inside a magazine. There is a collective voice of a group of people who want to share something. There are two reasons for magazines on paper. First, it’s the glamour, and to me real glamour comes from photography and interviews. This is because it is the place where people get intimate. The fashion world is organically a part of magazines — it’s the best place for fashion to be seen, appreciated, and evaluated. And secondly I think magazines need to survive because magazines are intimate. It’s one person to one person. It’s me to you. This photographer shot this model, with this stylist, for you. It’s like a film; everyone is working together to achieve a certain vision of the time and of the fashion. So when the reader opens a magazine they are immediately part of the world. A magazine has presence, it reveals something about people, about their dreams. It’s on paper, you can keep it and it gives you this possibility to interact. Purple is my life.”

Credits

Photography Terry Richardson

Text Ben Reardon

Styling Mel Ottenberg