Midnight on Friday at Tek 2000 in Hamilton. The vintage rock strains of Cutting Crew are speeding, pitched-up and condensed over a distorted 180 bpm kick drum. A hefty MC in a saggy grey tracksuit and baseball cap lumbers about the stage offering a barely discernible stream of rhetoric. The classic rave scenario, perhaps. Yet close your ears and this could be a house club. The bar is packed. No lightsticks or whistles in sight, and maybe only one E casualty, lunging around haplessly, eyes bulging in glassy oblivion. There’s a few lycra-clad babes gyrating on the edge of the dancefloor, sure. And two guys doing that classic double-speed skip-on-the-spot, like extras from an SL2 video. But the majority of this predominantly 16 to 19-year-old crowd — lads in check shirts, girls in T-shirt dresses and satin tops — display no interest in the fashions or conventions of yesteryear. And as the DJ shifts into the sneering, growling synth lines and rhythmic assault of Lowlands gabba, the dance floor fills up with awkward bouncing bodies, jerking and contorting themselves to the furious, punkish machine-gun invective emanating from the speakers.

This, then, is ‘Scotland the Rave’ 1996. Not so much the ugly sphere of drug addled, frenzied, nihilistic aggression that both the tabloids and city center clubbers would have it. Rather, the week-to-week social life of ordinary teenagers in satellite new towns like Hamilton, Motherwell, and Livingston. It is, however, a scene that’s in decline. Not due to any lack of popularity: the record labels are flourishing, the DJs booked for months in advance. The clubs, though, are closing. The same weekend we visit Trek 2000, the Metropolis in Saltcoats — one of a handful of hardcore venues left — announces it’s sacking resident DJs Joe Deacon and Billy Reid, and finding more house-oriented replacements. The Fubar in Stirling, another rave Mecca, recently moved to change half its nights to house, bringing in the Tunnel’s Michael Kilkie. Even rave giant Rezerection is planning to stage its next event in Burton-on-Trent rather than Scotland. In its wake, house promoters Streetrave are moving in to stage a massive all-nighter at the Royal Highland Exhibition Centre that features Pete Tong, Sasha, and BT.

“It’s ironic, because there’s probably more hardcore record labels in Scotland now than there are clubs,” considers Jamie Raeburn of Clubscene Records, whose sales have increased threefold over the past year. “Club owners are switching to house because they’re afraid they won’t get a license for a rave club. It’s sad, because there’s a 100 percent demand for it still. I mean, sacking Joe Deacon and Billy Reid from the Metro caused a sit-in, for God’s sake. It was about as popular as the poll tax.” He’s right. Out in Ayrshire, in the suburban sprawl of 60s concrete conurbations that stretches between Edinburgh and Glasgow, up in Fife and Elgin and Dundee and Stonehaven, on the housing estates; the piano-driven crescendos, the urgent warbling divas and the hammering basslines float free from cars, open towerblock windows and discount clothes stores.

And as the licensing boards clamp down on the clubs, following the precedent set by the closure a year ago of the controversial Hanger 13, few are rushing to rave’s defense. It’s nothing new, though. “This isn’t a new problem for the rave scene — it’s something we’ve had to cope with since day one,” continues Jamie Raeburn. “That’s why Clubscene magazine was started, because we couldn’t get our records reviewed in any other publication.”

Track the genealogy of Scottish rave and its marginalization, both geographically and culturally, has been a slow but sure process. Back in 91 and 92, hardcore was the sound of the city center. The break-beat-driven, lightstick-waving, Vicks-wafting ritual of the all-night rave was fundamental to the success of clubs like Pure and Soma. Middle class students, fashion victims, and hipsters would all make the pilgrimage to events at Livingston Forum, the Streetrave parties, Rezerection, Awesome 101, and Fantasia.

Ironically, just as the infrastructure of Scottish dance music was beginning to expand — bands like TTF gaining national recognition, labels like Clubscene and Evolution setting up — the popularity of hardcore in the cities began to wane. As the leather-trousered elitist backlash of progressive house and trance took hold, places like Glasgow’s Tunnel and Edinburgh’s Citrus Club began to maneuver themselves away from the fervor of rave which was gradually becoming that little bit too sweaty, that little bit too egalitarian, that little bit too populist for the fashion-conscious clubber.

Thus in the schemes and the satellite towns, in clubs like Fubar in Stirling, the Metro in Saltcoats and Hangar 13 in Ayr, this fiercely independent scene evolved. The economic infrastructure — provided by labels like Clubscene, Evolution, Twisted Vinyl, Notorious Vinyl, Stepping Out, Shoop (now folded), Massive Respect, Bellboy, Storm, and Screwdriver — flourished from 1992 onwards. Rave PA faves TTF hit the charts and a clutch of other groups sprung up in the wake of their success: The Rhythmic State, Ultrasonic, Q Tex, QFX, Bass X, Chill FM. And bereft of any national media support, they founded their own publications like Clubscene, or colonized existing Scottish monthlies like M8. Record sales grew.

Through 1993 and early 1994, Scottish rave seemed unstoppable. Sure, it was despised by the city center clubbing elite — all they saw was a kind of ‘lumpen proletariat’ of dance, eyes rolling, white gloves waving, jogging up and down to music they now deemed deeply unfashionable. It also received no national press recognition whatsoever. But the kids, well the kids couldn’t get enough. The raves swelled to gargantuan proportions. “The big one for me was fantasia at the SECC in November 93,” recalls Forth FM jock and ravers’ hero Tom Wilson. “There were 12,000 people there. It was unbelievable — the staging, the lighting, the bands.”

Meanwhile, Scottish house and techno heads were priding themselves on the innate intellectual inferiority of hardcore — in their eyes, an eternally static, remake of 1991’s cheesiest moments. And indeed, until around 94 when the Lowlands gabba sound emerged, many Scottish rave bands and PAs followed a fairly formulaic musical path. In fact, as long as you had melodramatic piano crescendos, accelerated diva vocals or, alternatively, dark Beltram Mentasm synths and over 150 beats per minute, you could be fairly sure of a place in the Scottish dance charts. Tunes like Q Tex’s “Natural High” and TTF’s “Real Love” hit the spot with their shrill treble melodics and high velocity programming. “When the scene first started here, you had piano anthems and you had hardcore,” remembers Scott Brown, who was recently voted top Scottish DJ by M8, produces as Q Tex and Bass X, and runs a multitude of record labels.

Around 92 and 93, when rave’s stronghold became the suburbs and the schemes rather than the city center, Scottish acts were tentatively finding their own identity and discarding the breakbeats which characterised the emergent English happy hardcore and jungle movements. And this was where the four-to-the-floor sound of Lowlands gabba came in, reckons Scott Brown. “The piano stuff got really, really stale and commercial and the English stuff had got really breakbeat led and people didn’t like too much of that up here. The only thing that started to come through was a lot of the Italian stuff on Brainstorm and some obscure German things. A lot of Dutch producers just hit the nail on the head: Sperminator’s ‘No Women Allowed’ and ‘Poing’ even, I reckon when that got into the charts it made a big impression on a lot of people.”

The rise of Lowlands gabba in Scotland was almost exactly tangential (if a little later) with the advent of ‘dark’ on the English jungle scene. A ferocious underground backlash against the commercial high watermark of rave. And even more despised and misunderstood than rave itself. By 1994, the fast anarchic spleen of high-bpm US and Dutch sound had usurped happy pianos and chirpy vocals as the Scottish ravers’ style of choice. “There was one Rezerection where every single DJ they booked from the US gabba scene,” recalls David Smit who runs Nosebleed in Rosyth, one of the handful of regular hardcore nights left north of the border. “And from then on, Lenny Dee was God up here!” Lowlands PAs Ruffneck Alliance, Human Resource, Charlie Lownoise, and Mental Theo headlined raves while English jocks like Loftgroover, The Producer, Scorpio, and DJ Freak, marginalized by happy hardcore down south, found their unrelenting kick drum-dominated sets in huge demand. “I’d say gabba finally peaked around last February or March,” considers Tom Wilson. “Rezerection seemed to be pushing the Dutch sound a lot. I even started calling myself Tom Van Wilson to try and get booked for it!”

Convergent with the invasion of Dutch DJs and PAs, Scottish acts Ultra Sonic, Chill FM, and Q Tex found a growing market for their records in Holland, Germany and America. In 1996, Saltcoats-based Ultra Sonic is a global concern. And, though you may have never heard of them, they sell more records worldwide than Leftfield, Orbital, or Goldie (around a million copies of their last LP, according to Jamie Raeburn at Clubscene). “Our albums sell best in the UK, Australia, and Germany,” reckons Mallorca Lee, Ultra Sonic’s vehemently anti-elitist 24-year-old spokesperson. “We’ve just landed a deal with Avex in Japan for our first album as well.” Tracks like their hammering, acid-tinged 95 hit “Check Your Head” not only assimilated perfectly into four-to-the-floor segue of visiting Lowlands DJs, but set raves alight all over Europe.

Closer to home, the DJ at Tek 2000 has moved through Scottish rave and gabba to the breakbeat-meets-kick drum amalgam of four-beat. A diminutive MC in white Ralph Lauren strolls confidently around the stage. And as the breakbeats roll from a vintage snatch of Beverly Craven into whiplash four-four and amply synths, the floor fills up and a kind of manic energy is almost tangible. Unwittingly, DJ Nicky Modlin’s set is itself a neat microcosm of the musical trajectory of Scottish rave. For after gabba’s 18-month stranglehold, the English four-beat sound has firmly established itself north of the border. “When gabba came in, a lot of people could get their frustrations out by dancing to the music and going for it full-on,” says Mallorca Lee. “But it died because promoters were putting on gabba solidly all night, and I don’t think anybody alive could physically dance to 200 bpms for 12 hours — although I suppose if you’ve got a skinhead and a sports tracksuit, you’ll give it a try!” The closure last year of Hanger 13, Scotland’s most popular gabba venue, after the Ecstasy-related deaths there of Andrew Dick, John Nisbet and Andrew Stoddart, signaled the end of Rotterdam’s reign.

And this perhaps was where the English sound came in. DJ Seduction’s four-beat strain of happy hardcore, which foregrounded the four-four beat, happened to tessellate perfectly with the records Scottish acts like Ultra Sonic, The Rhythmic State, and DJ Scott Brown were making. The result? Rezerection began bringing Slipmatt, Brisk, Seduction, and Dougal up to play and Tom Wilson, Mark Smith, and Scott Brown found themselves booked to play hardcore nights in England. “We seem to have a lot of crossover with the English happy hardcore sound at the moment,” notes Wilson. “As long as they get onto the ‘boom, boom, boom,’ eventually the Scottish crowds aren’t adverse to a bit of breakbeat here and there.”

Ironically, with the closure of all but a couple of Scotland’s hardcore nights and the increasingly restrictive attitude of councillors like Jim Coleman in Glasgow (now trying to instate a ban on chill-out rooms, which even contravenes the government’s harm reduction guidelines for nightclubs in its conservatism), the Scottish hardcore scene is now more alive in England than Scotland itself. “The Scottish rave scene is dead on its arse. I’ve seen it dying for the past year,” says Scott Brown. “It’s ironic, because sales are better than ever.” Jamie Raeburn agrees: “There’s nowhere left in Scotland for Scottish rave acts to play… all the venue owners want to do house now, because there’s this feeling that they don’t want to be associated with the image of the ridiculous Scottish raver — y’know, all big staring eyes. I mean, nobody wants to be associated with that any more. And as a result, we sell more records now in England than we do in Scotland and Northern Ireland.”

We’ve heard a lot in recent years about the the archetypal Scottish raver: top off, lightstick bearing, lycra wearing, grinning out from the pages of M8 in glassy-eyed oblivion. But just how true is it any more? According to Liz Skelton of drugs advice agency Crew 2000, that legendary Scottish overindulgence is becoming a thing of the past. “As far as our experience of the hardcore scene goes, there’s definitely been a shift. People do seem to be a bit more sensible and a bit more informed. People are taking time to chill out — we noticed at the last Rezerection that the dance floor wasn’t as packed as it used to be, there are times when more people are in the chill out. And they’re not wearing so many mad hats and things like that.” However, the closure of weekly hardcore nights has led to a trend for ravers to view tri-monthly events like Rezerection with an urgency and fervor that leads them to overdo it. “There are still ridiculously high levels of drug use going on,” confirms Liz. “It’s better than it was before, but it’s not ideal. Very young people come down, very inexperienced, who know very little about what they’re doing. They seem to make an exception for big events — ‘it’s Rez so we’ll go for it’ kind of thing. Instead of having a couple of grams, they’ll go for ten grams of speed and a couple of Es. Then they say they feel a bit funny and they don’t know why.”

After the government restrictions on the prescribing of Temazepam last year, Crew 2000 has noticed a decline in the ‘jelly head’ syndrome once synonymous with the Scottish rave scene. “A year ago you could spot people wandering about who were totally off their face on jellie. They’re still there, but not half as much as before.” And as bpms revved up to 180 and 200 in 1994 and 1995, when Lowlands gabba peaked, many noticed a fast music-fast drugs correlation. “When the gabba sound came in, people stopped taking so much E and started taking speed to keep up with the music,” observes Jamie Raeburn. Liz Skelton agrees: “There’s been a general trend towards less E and more speed for some time now.” Sadly, just as the hardcore scene seems to be absorbing the message of moderation and education that Crew 2000 has taken to ravers across the country, there are few clubs left to exemplify this slightly more aware sensibility.

Where now then for Scottish ravers? The most obvious answer seems to be traveling on coaches down to events in Newcastle and Doncaster every weekend. Tom Wilson sees many similar qualities in the accelerated trance-meets-rave synthetic of nu-energy. “I reckon that Tony De Vit sound will take over from hardcore, the fast stuff — Red Jerry, Tall Paul — music with balls.” With Streetrave’s all-nighter, Colours, in the offing this month at the traditional site of Rezerection, it could well be house. In Jamie Raeburn’s opinion, the exodus from rave to house has already begun. “You’ll find the same people going to Colours and Cream as the ones who were going to raves one, two and three years ago.”

And whilst the house and techno purists might bask in the knowledge that ahrdcore didn’t last, their complacency can only be shortlived. “The good thing about hardcore was that there was absolutely no way you could associate it with what was going on in the Mecca discos. This was 200 bpm music and an underground scene, whether you thought it was credible or not,” concludes Jamie. “It was outside the major record labels, it was working class, the people into it loved it like nothing else… not there’s no way you’ll find that in a house club these days.”

Credits

Taken from The Supernova Issue, No. 153, June 1996

Text Bethan Cole

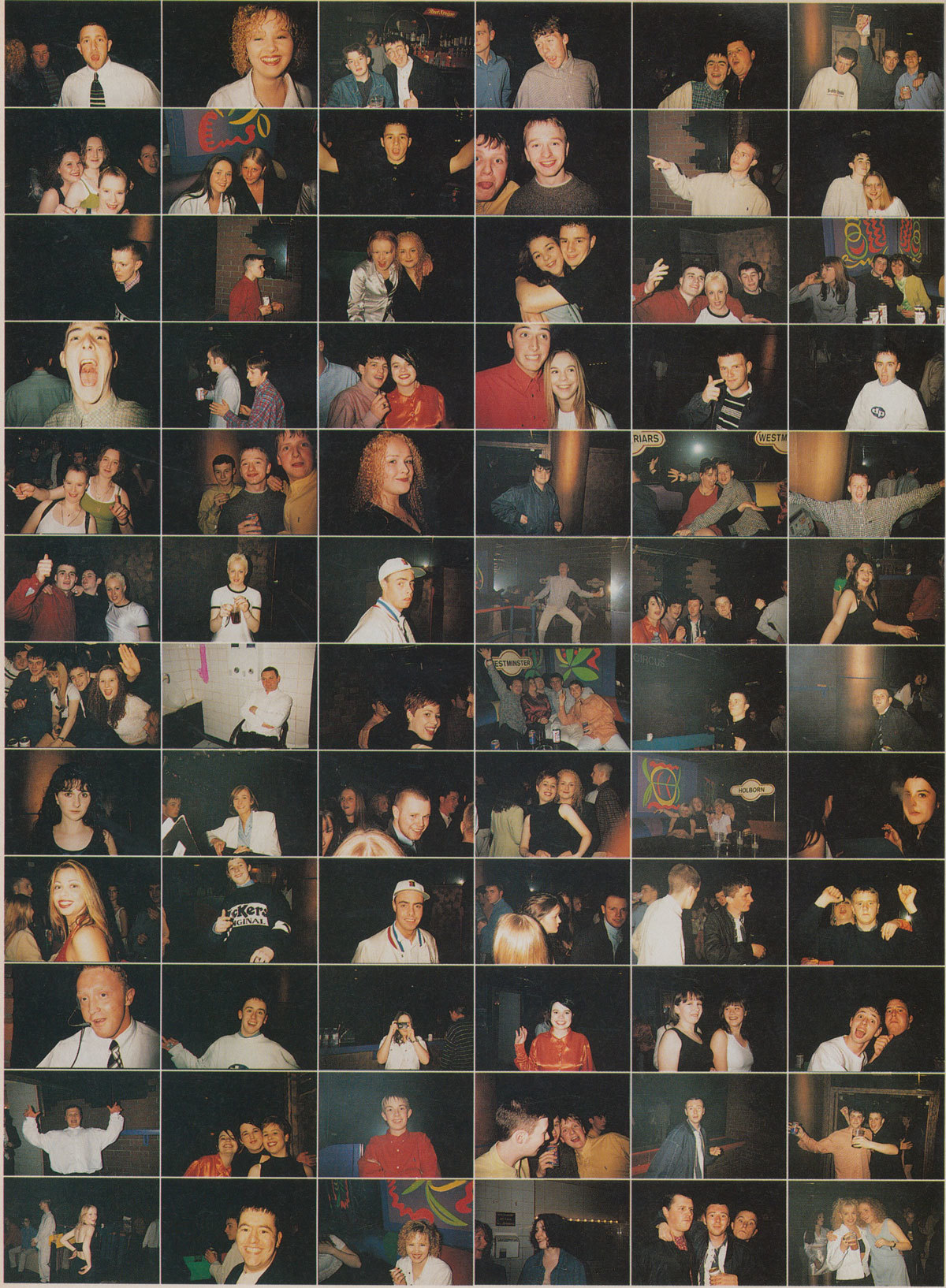

Photography by clubbers at Tek 2000 using Kodak Fun Flash cameras

Photographic Co-ordination Bethan Cole and Kevin Lewis

Thanks to MC Bee, Simon and everyone who helped out at Tek 2000