Over the course of his 40-plus-year career, Andras Bánkuti has photographed a dizzying array of subjects: ballet dancers mid-rehearsal, dust-covered miners, museum-goers of the former Soviet Union, political demonstrators, and Paris cityscapes. In the 80s and 90s, as communism in his native Hungary collapsed and transitioned into capitalism, Bánkuti chronicled day-to-day life in his country for international publications including The Guardian and The New York Times. While producing his own photojournalistic work, he was also head of the photo department for a Hungarian economics weekly, and a founding member of the Mai Manó House photography gallery in Budapest.

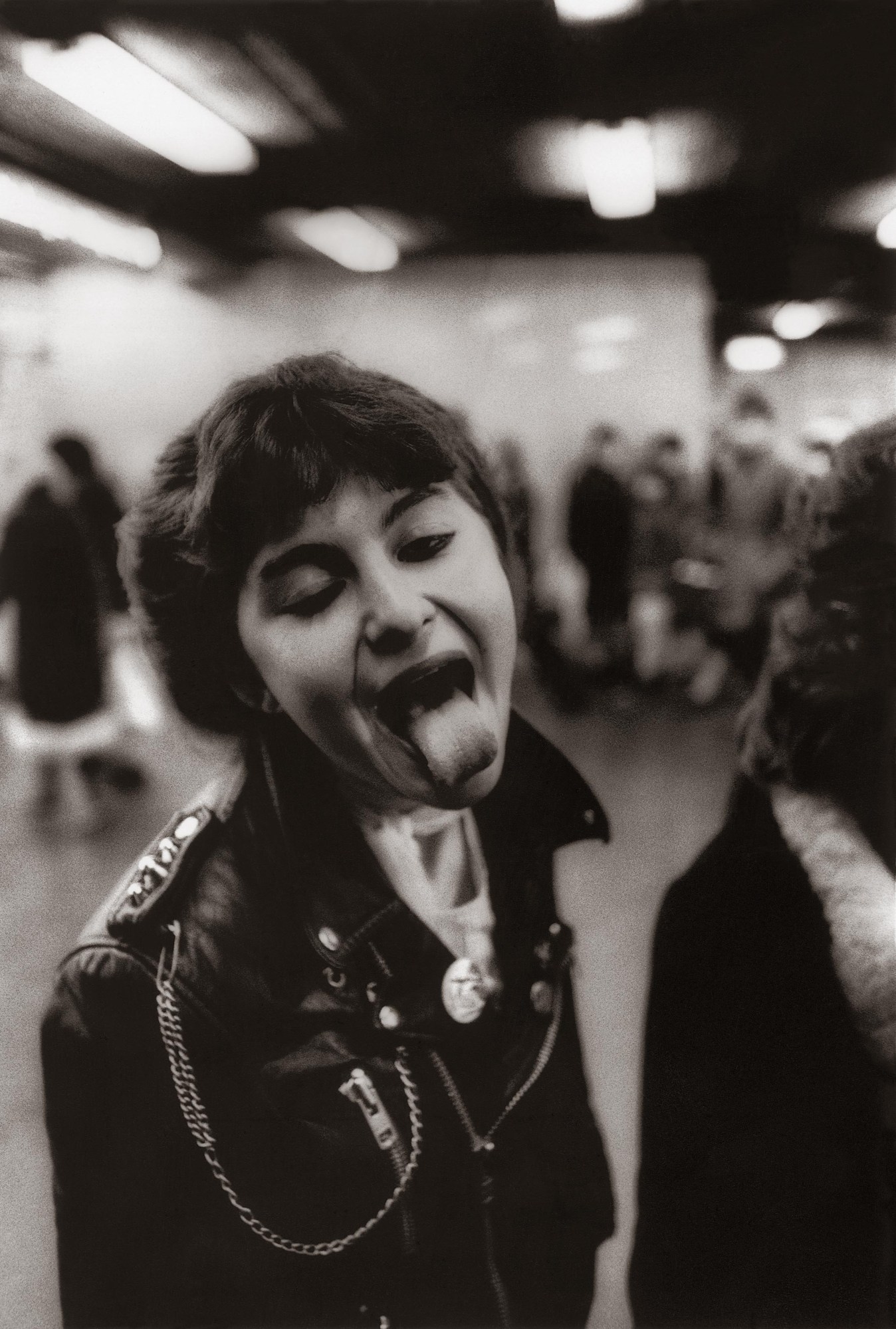

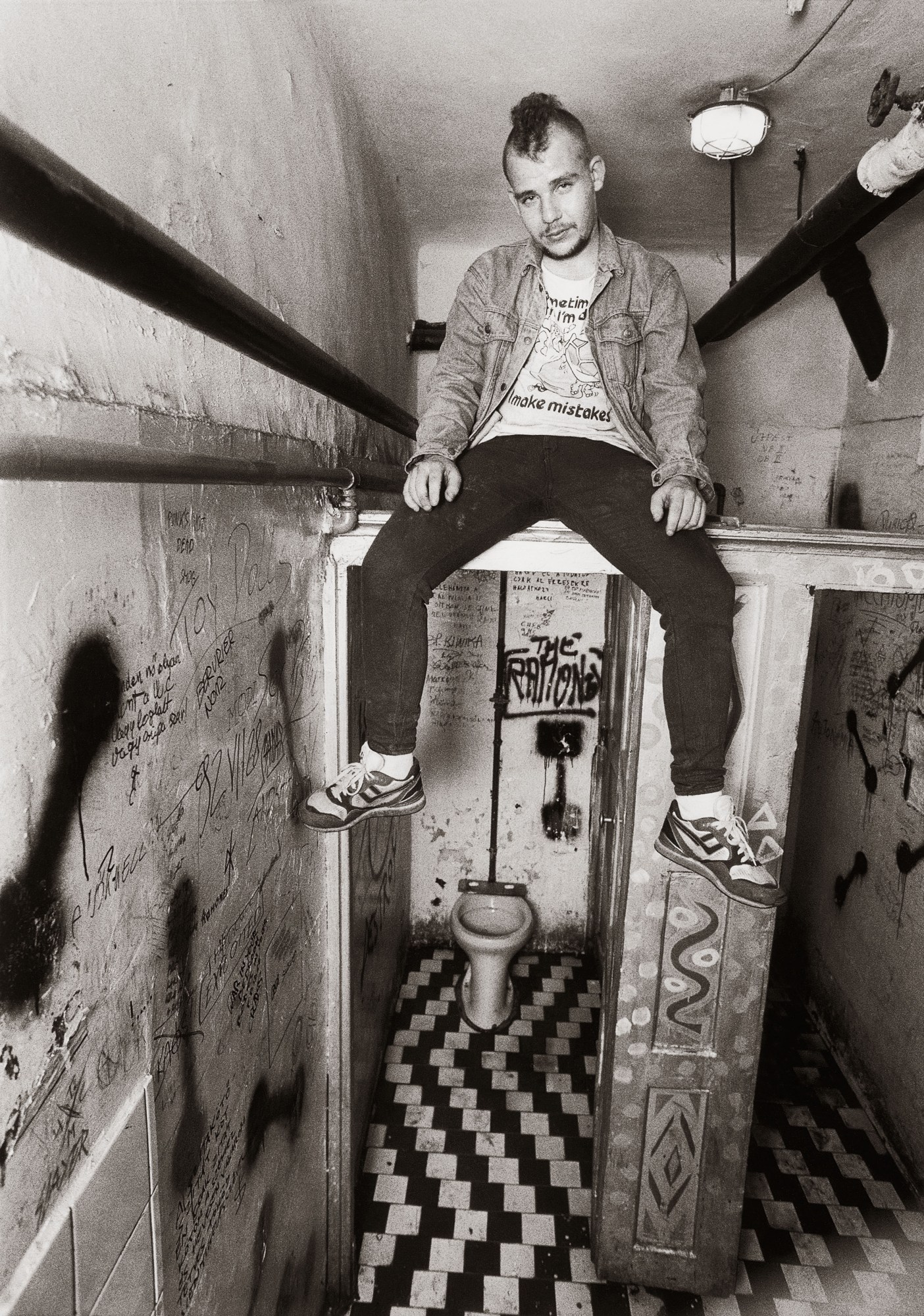

While he specialized in capturing economic and political shifts on a national scale, he also used his camera to tell the personal stories of those on the margins. During the 80s, he ingratiated himself with Budapest’s clandestine punk scene, facilitated by a mix of earnest curiosity and clever bartering with photographic prints and free beers. Here, Bánkuti talks to i-D about the Hungarian punk scene’s evolution from a risky subculture to a lifestyle, and how he knew the true badasses from the posers.

Did you come from a creative background?

I was born to a bilingual family — my Mom was Russian, my Dad Hungarian — so I was brought up in two cultures. My father was a renowned radio reporter, whom I often accompanied. My mother, who loves visual arts, took me to museums.

How did you get your start as a photographer?

I was planning to be either a historian or an economist, but during my last year of high school, I was hospitalized for months due to a serious illness, and had no way of preparing for my university entrance exams. I’d attended an extra-curricular course in photography, so I decided to enroll in a vocational photography school. I’d always enjoyed taking pictures; I initially wanted to work as an archaeological photographer.

Which photographers influenced your aesthetic and approach?

The greatest influence came from colleagues at the beginning of my career. During the 80s and 90s, we all worked with film and gave each other honest criticism. It was a creative community, which is hard to find today, as photographers send in their work online and hardly know each other. Documentary photography as a tradition was very strong in Hungary. We all wanted to measure up to the great generation of Hungarian photographers who left the country and became world-famous: Robert Capa, Brassaï, Martin Munkácsi, László Moholy-Nagy, André Kertész.

Outside Hungary, the works of Dmitri Baltermants, W. Eugene Smith, Donald McCullin, Salgado, Mary Ellen Mark, and Annie Leibovitz had a huge impact on me.

Why did you choose black-and-white film?

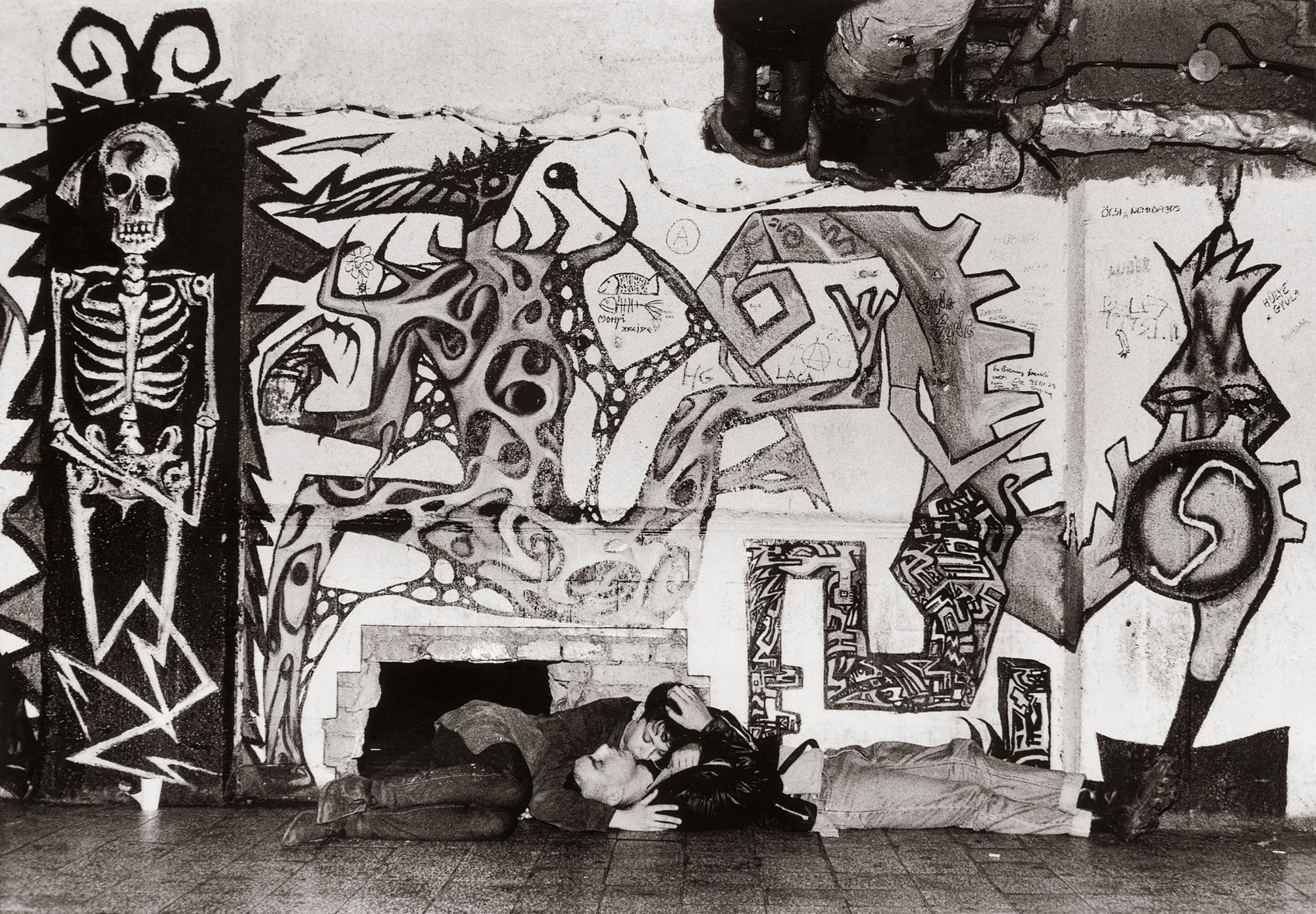

When I started taking pictures, color film was limited in Hungary, so there was a practical reason. But also, I “saw” pictures in black and white. Punks especially relate more to black and white.

How did you get into the punk scene? Were you chronicling it as an outsider, or were you part of the community?

The punk community in Budapest, like in all major cities in Europe, was quite isolated. They stood out in their provocative outfits and — as someone whose intention was to record everyday life — I felt I had to learn more about them. I was not part of their movement, but I took part in many of their events: gigs and private parties. I spent a lot of my weekends with them, making friends, until I stopped following their lives around the mid-80s.

What kinds of conversations did you have while shooting this series?

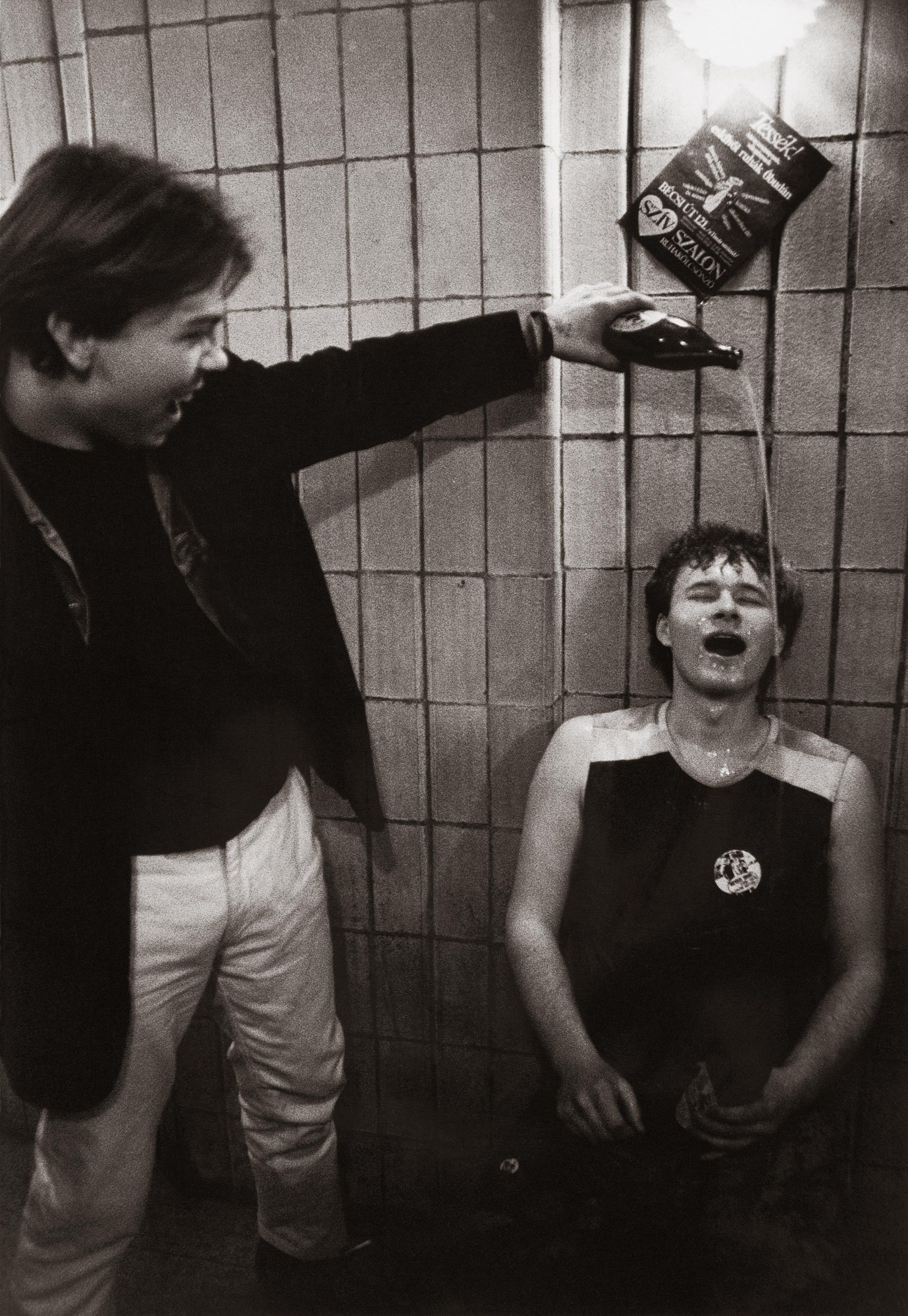

I contacted people at one of the largest subway stations of Budapest, where the scene would commonly gather. I went up to them, introduced myself and told them about my plan for a larger-scale photo essay about their lives. Some of them agreed to be in my pictures; some didn’t trust me and said they wouldn’t mind if I was around, but I couldn’t take their picture. I returned every week and always brought small prints from the last week’s shoot as presents — this was before digital cameras. Eventually, almost all of them agreed to have their pictures taken. I had very few troubles; people were not as aggressive as they are these days. Once, a member of a punk band jumped off stage, swearing and threatening to beat me up if I dared to take his picture. I had to buy the rights for taking photographs by paying for drinks.

How did punk style factor into your vision?

I obviously met some “fashion punks” who would come to the parties in their everyday outfits, change in the toilet, and after three or four hours, once the party was over, they would change back to their conservative attire and go home. They were afraid their parents might not let them go to these parties, so they didn’t want me to take their pictures. This was just as well; I was not really interested in them. I didn’t care for the superficial — I wanted to know punk people, who they were and what they were into.

How did the punk scene evolve over the decade you photographed it? What role did censorship play?

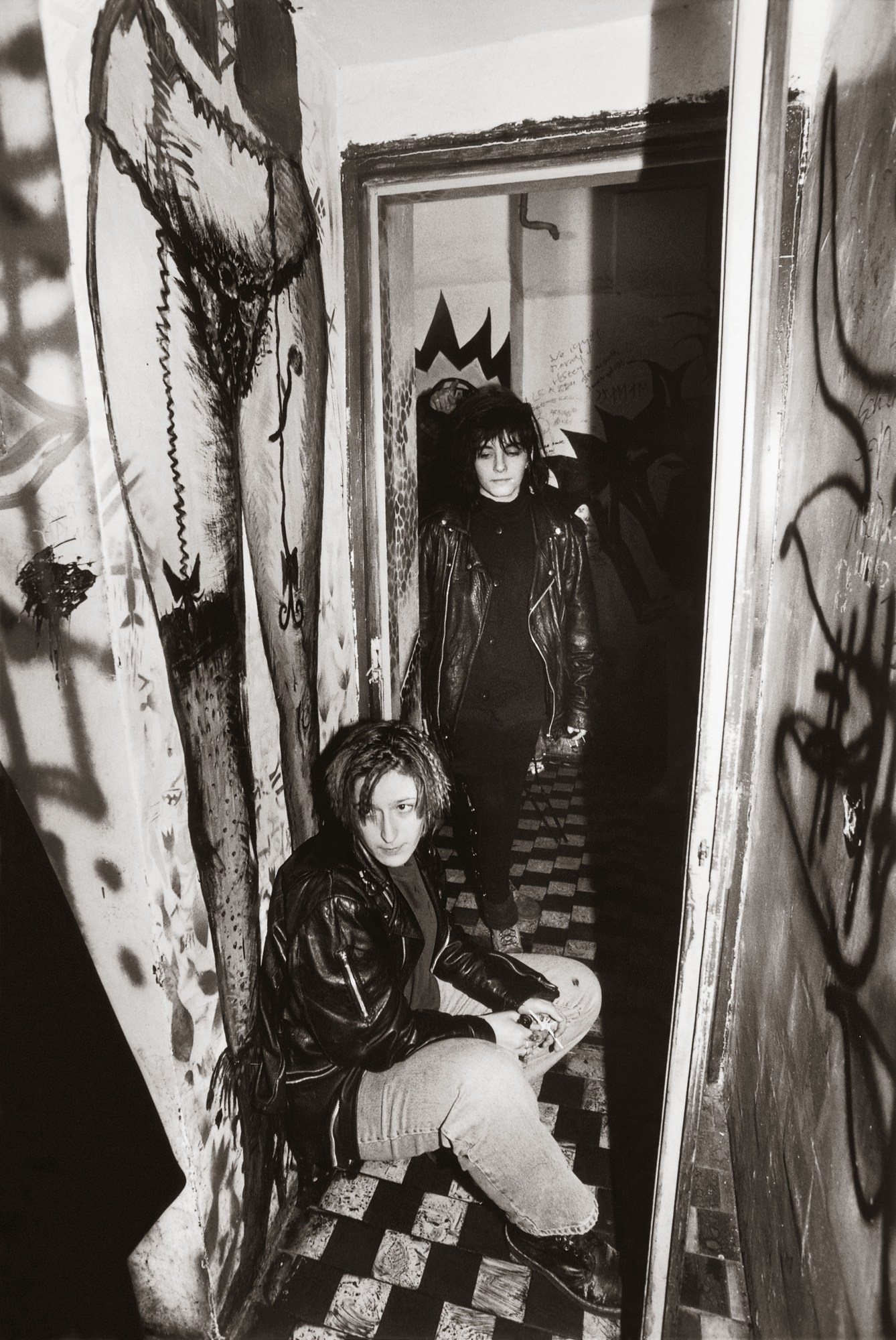

During the 80s, there were a lot of taboos, a lot of issues the media was not supposed to report on. The punk movement was one of them; drugs were another. Hungarian punks used glue to get high, in those days. There were a few punk bands, including CPg [known for controversial, anti-establishment lyrics openly condemning the state authority], who were later imprisoned. My pictures were first published in a police magazine as evidence found in the homes of the band! The pictures were not attributed to me, so the police didn’t catch me, but as a precaution, I hid the negatives. It wasn’t just my freedom I was concerned about, but those who were in the pictures. I didn’t want to put anyone in danger.

How was the scene different in the 90s versus the 80s?

During the 80s, punk bands might only get one day in culture centers, whereas in the 90s, they had their own clubs decorated by their own artists. The movement was established and accepted as a lifestyle and music genre. Kids who had to change in and out of punk attire disappeared and it stopped being taboo. Publication was limited only by the taste of the photographers or their magazines, not censorship.

How did the punk series feel different or similar to your other work, showcasing Hungarian society in political and economic transition?

My punk series has more portraits, but in general, I work in a comparable style and composition for most photo essays. The way I research the issue, make contact with people and get to know them is similar — even in my ballet series.

“Valeurs Marginales” by Andras Bánkuti is on view at Institut Hongrois in Paris until December 16, 2017.