This article was originally published in 2016 for Romeo + Juliet’s 20th anniversary.

In early 2016, during a live broadcast of Glenn O’Brien’s interview show Tea at the Beatrice, for which the esteemed editor was interviewing Baz Luhrmann, O’Brien asked the director: “How do you make the un-makeable deal?”. Though Luhrmann’s films have grossed hundreds of millions of dollars, there is something incredulous about each of them. The executive producer of his first feature, Strictly Ballroom, died suddenly during production — throwing the fate of the 1992 romantic comedy about the competitive world of ballroom dancing into perilous uncertainty (Luhrmann later received a phone call from Cannes telling him he had a single day to decide if he wanted to premiere the film at the festival). For Moulin Rouge!, his bohemian cabaret set in the 19th century, Luhrmann secured the rights to iconic songs by David Bowie, Dolly Parton and Elton John by cold-calling the artists’ teams.

But Luhrmann’s most “un-makeable deal”; the biggest “how did this movie actually happen” moment? His two-hour, action-packed, star-studded blockbuster in which the only words spoken are Elizabethan English: Romeo + Juliet. The 1996 sensation more than succeeded in its aims of refashioning Shakespeare for the MTV generation. It brought in $147.5 million by soundtracking sonnets to Radiohead and Garbage, and outfitting the Montagues and Capulets in Prada and D&G.

There have been plenty of wildly popular adaptations of Shakespeare’s tale of star-crossed lovers, from West Side Story to High School Musical. Yet these successful riffs don’t ever retain its “thine’s” and “thou’s.” Luhrmann, who developed his sumptuous dramatic style working in theatre and opera, didn’t dream of backing down from the Bard’s original language, but sought to construct a unique universe for it to live in anew. According to the film’s production notes, Luhrmann calls this a “created world” — a self-contained space that’s rooted in a pastiche of iconic imagery from religion, technology, folklore and pop culture. This created world “afforded production designer Catherine Martin and costume designer Kym Barrett an incredible amount of aesthetic latitude, but their creations were always firmly tethered to Shakespeare’s words, story.” This is because, Martin argues, Romeo and Juliet’s Verona was a product of Shakespeare’s imagination, too: “It was his vision, as an Englishman, of this mythical, Italianate country, where everyone was passionate and hot-blooded…essentially, the Verona in which Shakespeare set his play was a created world itself.”

Romeo + Juliet‘s hyper-colourful created world is Verona Beach, a blend between Venice Beach, Miami and Mexico City, where most of the film was shot. The created world is partly moored in the aesthetic and cultural traditions of these regions. The decrepit carnival rides harken back to Venice Beach’s chequered history; in the 50s, as in this film, the once-thriving tourist hub became a Petri dish for gang activity. Martin made phenomenal use of Mexican religious folk art throughout her lush and romantic sets (and nabbed an Oscar for Art Direction in the process). Yet Luhrmann’s created world does not only define the physical space his characters occupy. They, too, are anchored in that pastiche of icons — from the way they act to the way they dress. Luhrmann named The Godfather, the heightened reality of Fellini films, and Tennessee Williams’s severe Southern belles as influences on his characters’ mentalities and choices. Though the Montague and Capulet boys have inherited their parents’ feud, these sparring children share a common rebel cause: defying the older generation. So how to create a link between the two households while still maintaining their distinct identities? And how to tether that youthful rebelliousness to the created world? Fashion.

When Luhrmann described this generational divide, he did so with designers. The senior Montagues and Capulets, he said, “have more of the 1960s-1970s-Yves-St.-Laurent-Jackie-O. look about them, whereas the younger generation has rejected that.” That rejection takes two distinct forms: for the Capulet clique — led by John Leguizamo as Tybalt, the Prince of Cats, it meant sleek, sexy and super-tailored looks courtesy of Dolce & Gabbana’s defunct diffusion line D&G. The Capulets favour mostly black garments with streamlined silhouettes, but drip in decorative embellishment: they’ve adapted their gun holsters as high fashion accessories, and wear their shirts tucked in to show off their bold belt buckles. One of them even has a grill with “SIN” etched into it.

Though the Montague boys are of the same comfortable social class as the Capulet clan, their garb is much more easy and utilitarian: unbuttoned Hawaiian shirts, baggy workwear-inspired pants and shorts, combat boots or Chuck Taylors. “With the Montague boys, it’s sort of a Vietnam feeling,” costume designer Barrett explained, citing the end of the war in the mid 1970s, “when the soldiers wore Hawaiian shirts and shorts and indigenous hats. They invented their own way of wearing clothes, to suit the climate and the surroundings.” Though the Montagues don’t have quilted, velvet bulletproof vests like the Capulets, this rag-tag team is not without its own unique code of ornate decoration (shout out to Mercutio at the Capulet party, who looks like he walked off an Ashish runway). They don’t need bling, their Hawaiian shirts are vibrant enough; they don’t slick back their hair to show off their hand-crafted holsters, they dye it pink and spike it up. The factions are distinctive, but both wear their rebellious attitudes on their sleeves through clothing that connects to the created world they share.

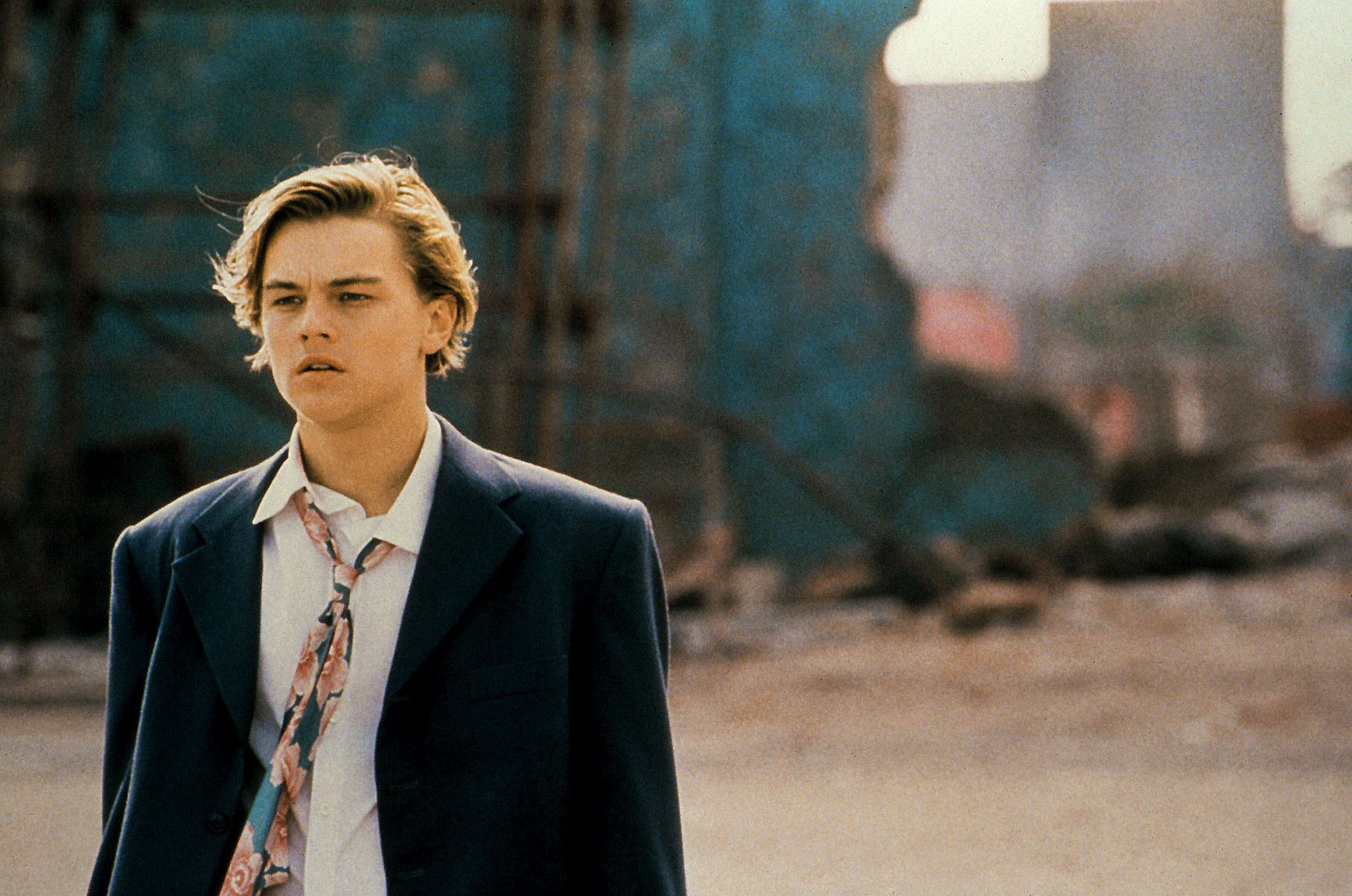

The rebellion to this rebellion: Romeo and Juliet themselves. Though she hails from the house of Capulet you don’t see Claire Danes in a transparent black feather slipdress (or, unfortunately, this rhinestone-studded “tomatoes potatoes” bodice from D&G’s 1992 collection); just as you don’t see baby-faced Leonardo DiCaprio with pastel pink frosted tips in a giant pair of fire engine red Dickies, as if he was heading to a No Doubt gig after his gunfight. Barrett instead made their clothes, “the simplest of all, very clean lines, not embellished at all.” And to do it, she went to Prada.

In the years since this film was released, Miuccia Prada has designed collections of noirish Hawaiian shirts, riotous clashes of colour and punkish embellishment. But in the mid 90s — when Miuccia was in the beginning stages of building her family’s leather goods brand into a ready-to-wear empire — it was her “pure, understated lines” that attracted Barrett, and the rest of the world, to the label’s subtle elegance. Having only launched menswear in 1993 (but already tapping young actors for its campaigns), Prada created Romeo’s just-boxy-enough navy blue wedding suit, complete with a crisp cotton shirt and pink floral tie, an homage to his Montague heritage. Juliet’s looks are similarly subtle, simple and down to earth — even her angel costume at the Capulet ball. Luhrmann cast Danes on the strength of My So Called Life, but Barrett stripped away Angela Chase’s flannels and sweaters, leaving Juliet, in one scene when she’s waiting for the Nurse to dish about Romeo, with just a white t-shirt and jeans.

Youthful rebellion takes many fashionable forms in this film, but every style choice springs from Luhrmann’s created world (just like how some designers create a world for their clothing on the runway). The cocktail of minimalist custom Prada, Vietnam-meets-mall-rat, and ultra sexy D&G doesn’t seem probable outside Luhrmann’s imagination, just as scoring Shakespeare to Butthole Surfers and The Cardigans also seems like it would be a disaster. Yet these choices are precisely what makes his adaptation so unique and enduring, and what other directors should consider when approaching such adaptations. I’m no Arthur Miller fan, but if someone remade The Crucible with Vetements, you bet I’d buy a ticket.