Wilkes-Barre boasts a population of just over 40,000. It forms a fraction of northeastern Pennsylvania, a metro-region home to 560,000 people. These figures pale in comparison to the number of images photographer Mark Cohen has shot of the Rust Belt city’s streets over the past five decades. He estimates there are over 800,000 negatives he’s never even developed.

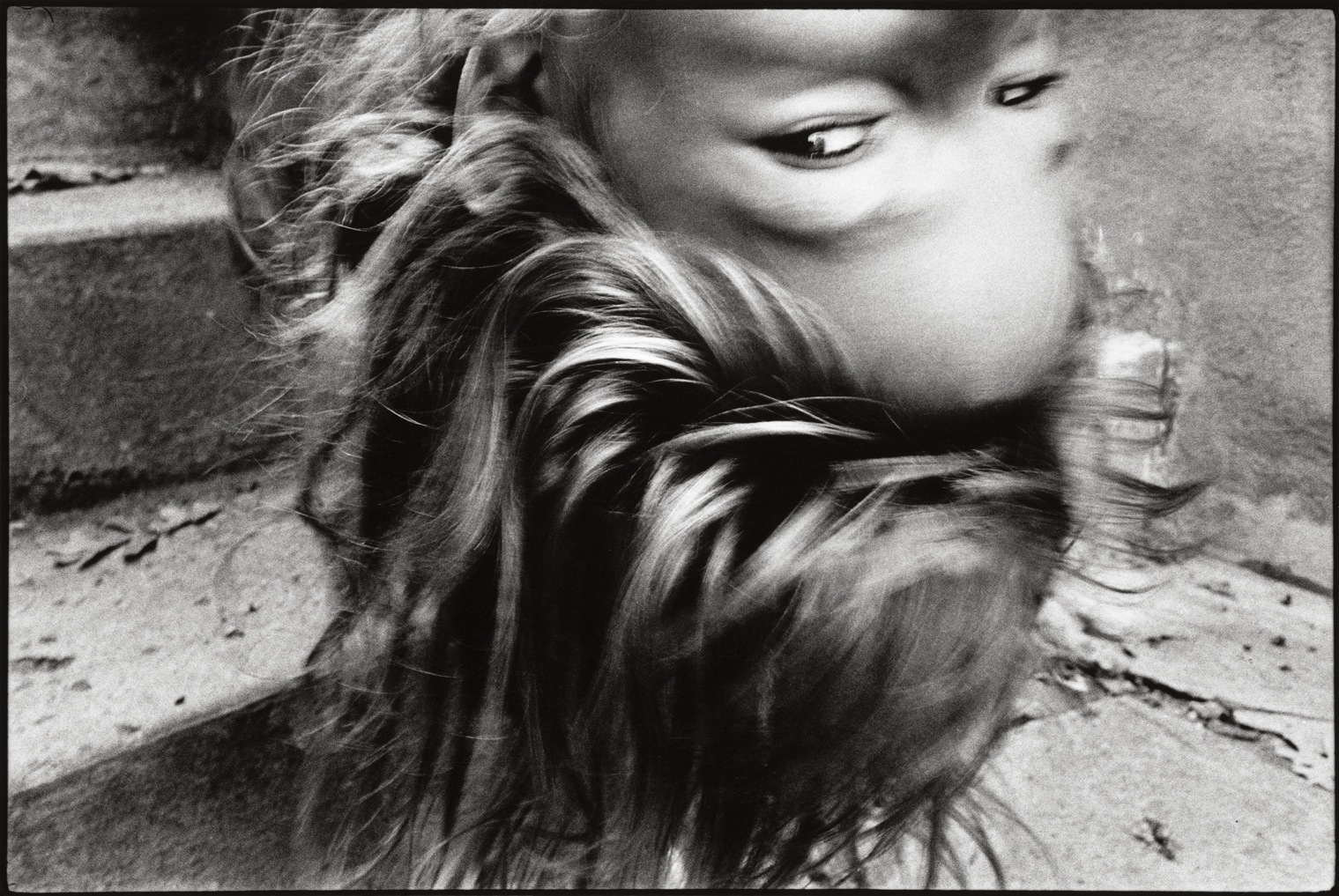

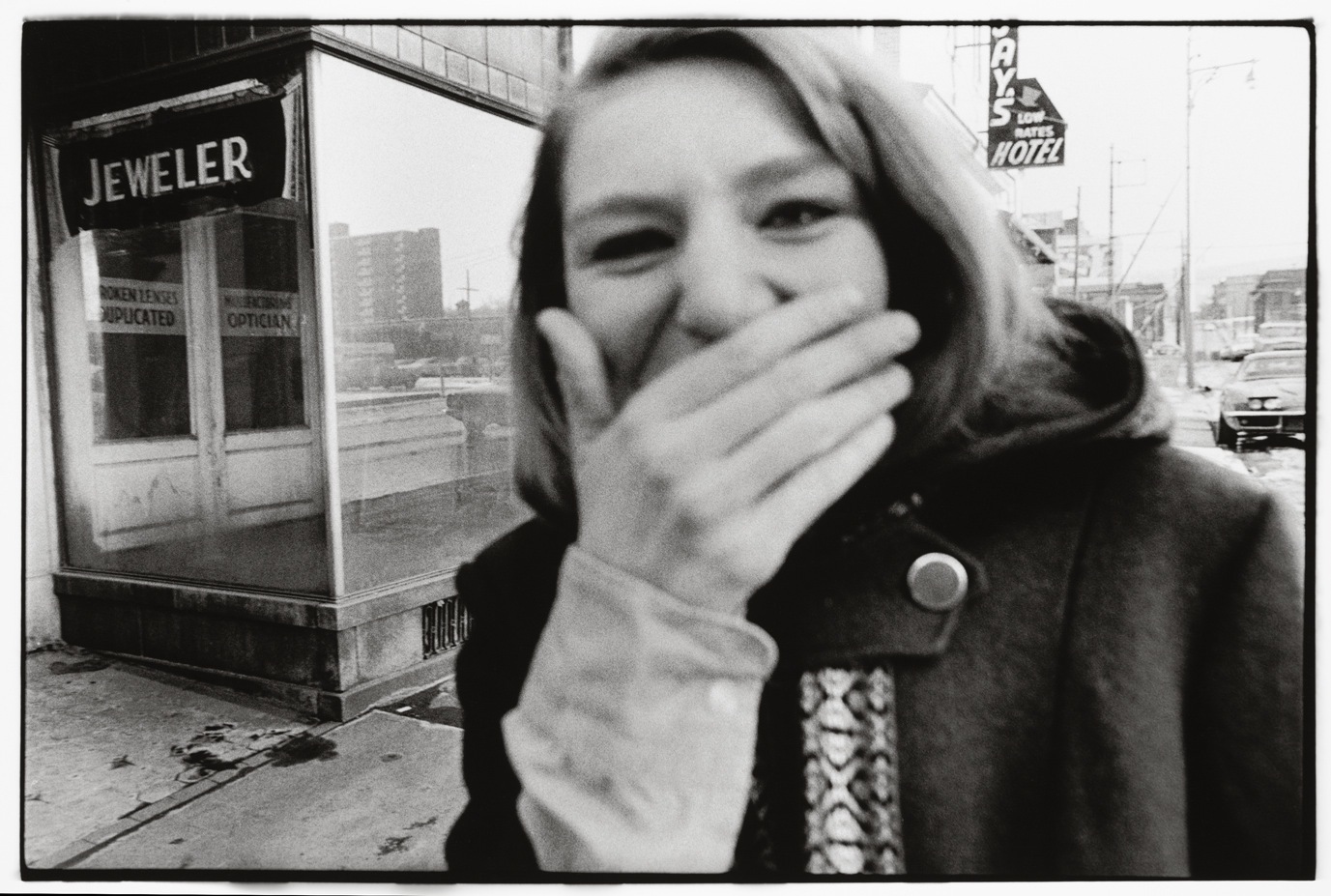

Although he never fled his home town to court New York City gallerists or enroll in an MFA program, Cohen is one of street photography’s poetic pioneers. His confrontational, invasive, shoot-from-the-hip style has become standard street practice, long after one of his earliest exhibitions: a 1973 solo show at the MoMA (mounted when Cohen was just 30-years-old). His methodology has been perhaps most notably evolved for the digital age by Instagram’s favorite sidewalk sniper, Daniel Arnold. This is something Cohen knows. “If you look at the advertising in Vogue, you’ll see a lot a pictures that look like I might have taken them 30 or 40 years ago,” he tells me when we speak on the phone. “In the New York Times, you see pictures with people’s heads cut off all the time. When I first did that, it was seen as extremely radical, but now, it’s very common.”

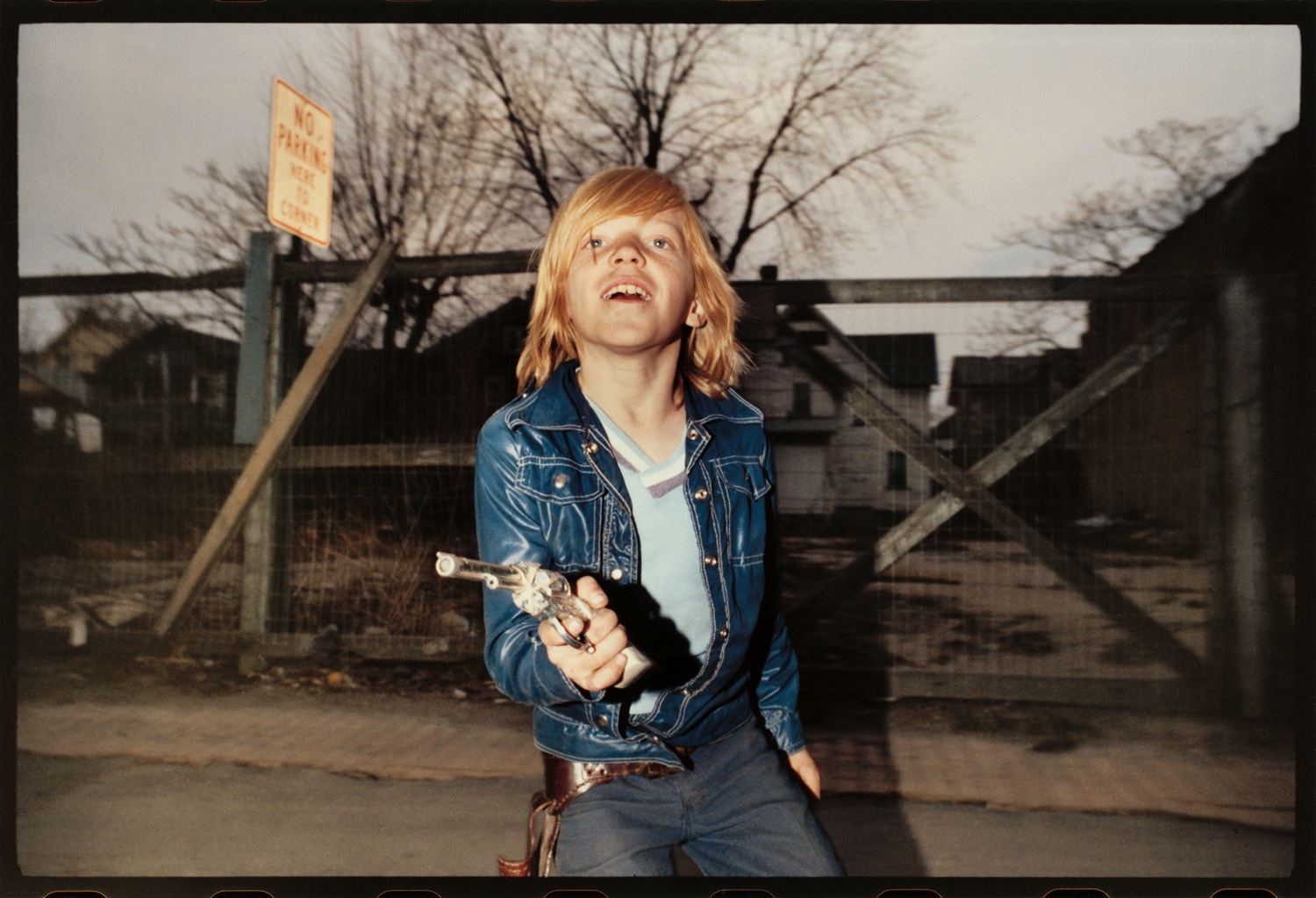

In spite of his indelible influence and prolific output, there has never been a career retrospective of his work — until today. Frame, a new book published by the University of Texas Press, features over two hundred and fifty of Cohen’s aggressive, emotional images from moments when Wilkes-Barre seemed like the wild west. “It’s more comprehensive than any other books I’ve done because it incorporates color and black and white pictures, and features almost a hundred pictures that have never been published before,” he says. As he celebrates Frame‘s release, we catch up with Cohen to find out more.

Did selecting the images for Frame help you realize anything new about them?

Once I saw the book in print, I felt very good about adding certain pictures I’d make on various trips. 99% of my work was always done in Wilkes-Barre or Scranton, but I wanted to add pictures that I took on trips to Spain, Ireland and Mexico. I put some of those pictures into the mix, and I think they really became strengthened alongside the typical work I was doing in a small town.

You moved to Philadelphia about three years ago. Have your methods of shooting changed in your new location, or over time?

It’s all very much the same. I didn’t come down here taking pictures of the Liberty Bell; I’m taking pictures of broken bottles, chips in concrete, architectural details, a person’s elbow, the guide lanes on the street — very similar to what I might have done in Scranton or Wilkes-Barre. I’ve made enough of a body of work over these three years in Philadelphia, and I’m thinking about trying to do a show of new work that’s just been shot here. If you look at it alongside pictures I made 20 years ago, you see very distinct similarities. I’ve even been making the same size prints, 16 x 20 inches, for almost 50 years. It’s sort of like using the same alphabet.

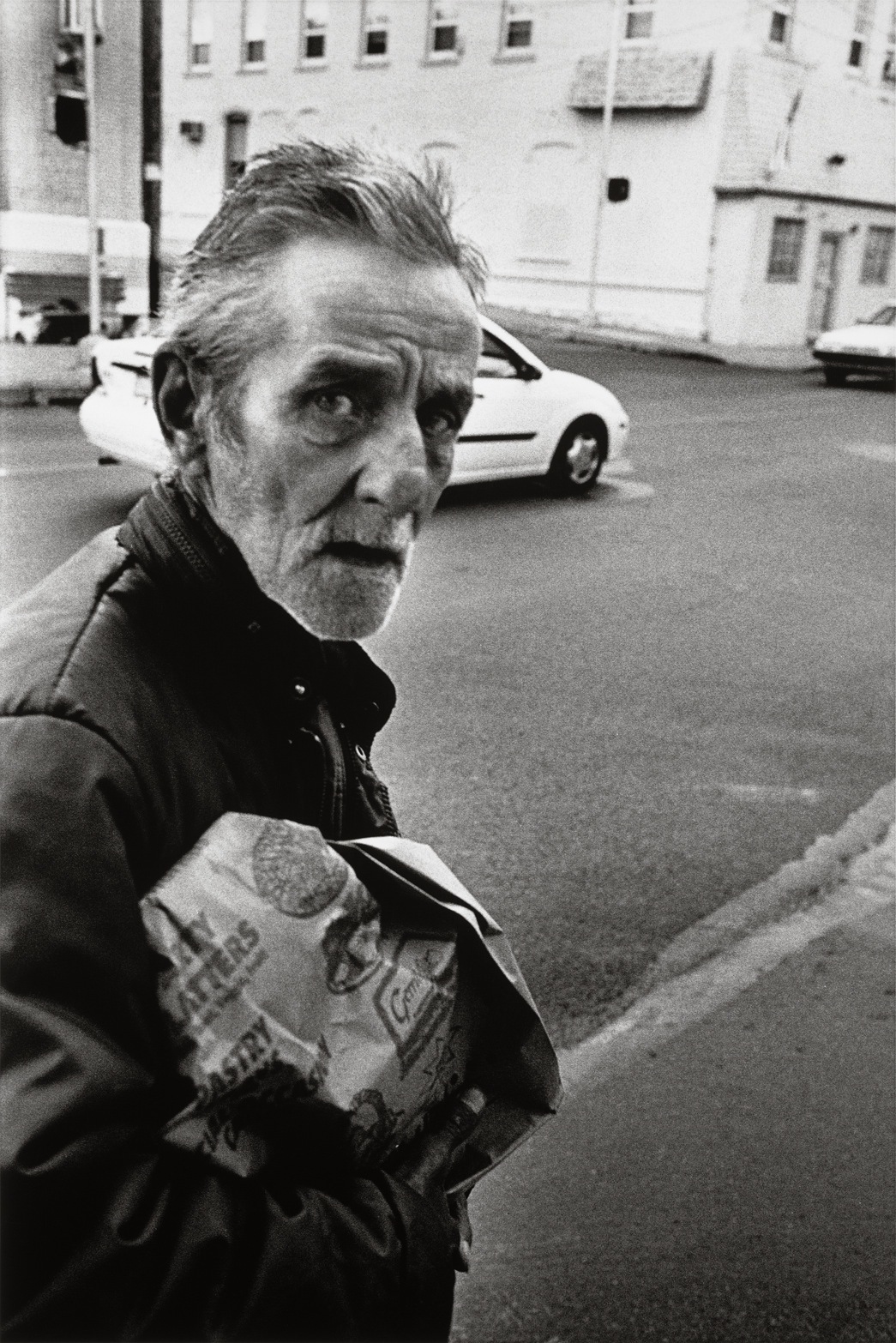

I’m really compelled by the clothing in your images. In some of the earlier photographs, there are so many great tweeds, leopard prints, and thick sweaters. What draws your eye?

A lot of the pictures are of old guys in overcoats. It’s not really about fashion, it’s more of a story: this guy’s on the edge of things, he’s like 75 and he’s out in this alley in Wilkes-Barre or he’s walking on the street and I just take a picture of the buttons that are on his coat or his hand in his pocket. They’re not pictures about fashion, they’re about bundling — about protection. They’re guys on the edge of their lives in a certain way, and those images are sprinkled throughout the book. There’s an autobiographical thread to Frame that’s very hard to explain even to myself. But it’s about life, your work is really about your life in some ways. That’s what happens with these old guys. Everyone sees themselves going through time.

What do you hope people take from this book?

I think a key thing that the book demonstrates is that you can make a whole body of work from one little town and you don’t have to go right to the middle of New York City or Paris to work as an artist. That work is almost all made within five or 10 miles of my house. You can make a tremendous body of work with your own space that you know about. You know how they say teach what you know? That’s one of the main things you can see in Frame. The vocabulary in those pictures is very broad; there are pictures of knees and coats and snowflakes. There’s a lot of stuff there, a lot of variety, and it’s all in this one very small town. I would go to New York and show people the pictures, but I didn’t work in a group. I wasn’t in a school, I wasn’t in an MFA program. It’s just something that evolved of its own nature. I was left to my own devices.

Frame is available here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography Mark Cohen, courtesy University of Texas Press