This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Timeless Issue, no. 371, Spring 2023. Order your copy here.

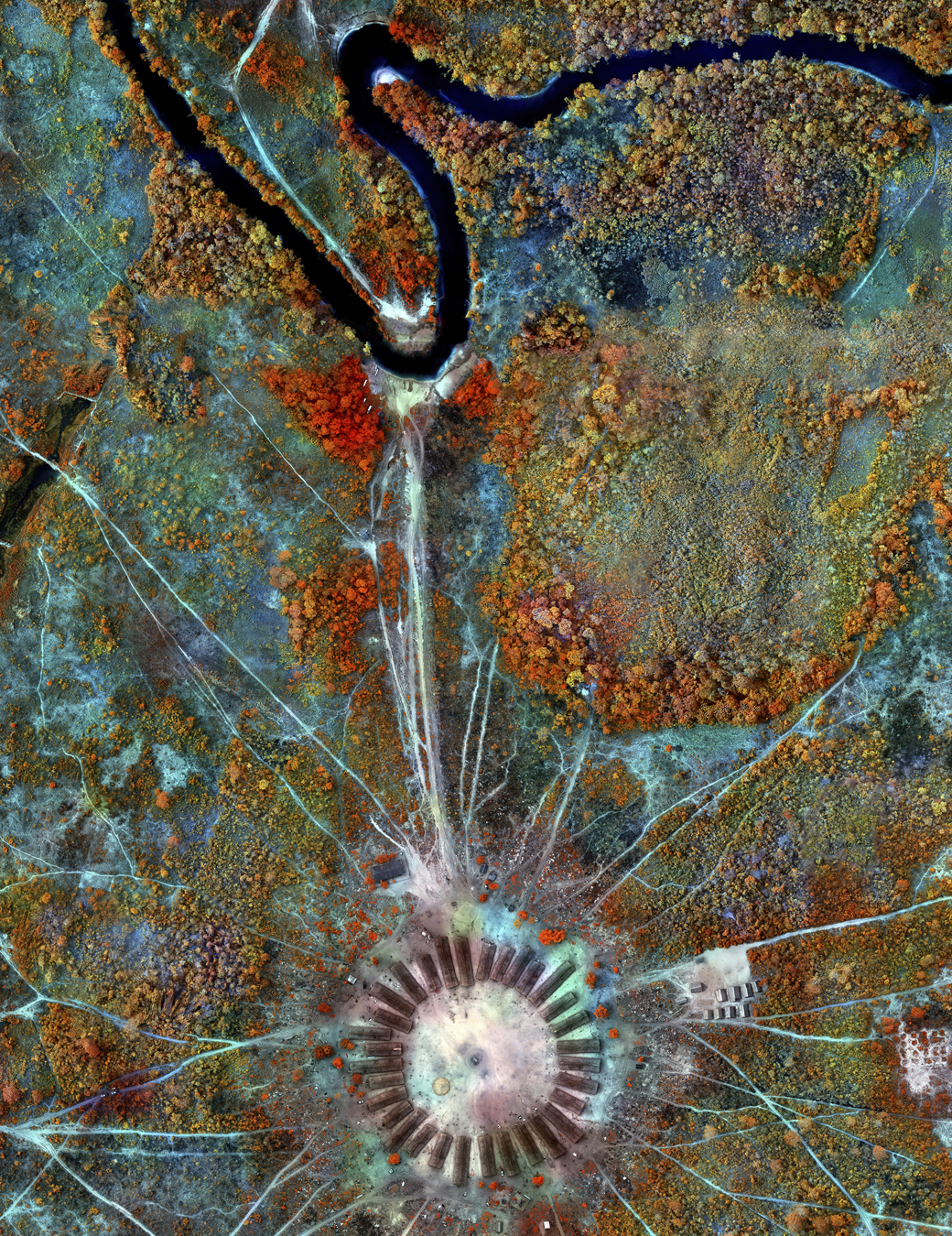

Starting in 2019 and through the pandemic, I worked in the Brazilian Amazon on an immersive video artwork, Broken Spectre, with longstanding friends and collaborators, composer Ben Frost and cinematographer Trevor Tweeten. Shifting in scale and medium, the film takes a careful look at the processes involved in the destruction of the world’s largest tropical rainforest by agribusiness, logging and mining interests – almost 99% of which, according to a recent report, are illegal. These fronts of deforestation document man’s rapacious incursion into one of Earth’s most biodiverse ecosystems.

As a case study of climate change, what’s particularly shocking about the Amazon is that only 1% of the original forest was lost to deforestation before 1970. Brazil’s military dictatorship, influenced by neo-liberal ideas from the United States, began construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway in the early 1970s with the stated objective of opening up the Amazon for “development”. To facilitate this, the dictatorship established a government agency named INCRA – the National Institute of Colonisation and Agrarian Reform – which was tasked with resettling impoverished and landless workers along the route of the highway, to colonise the forest and work the land. INCRA was also established to support large scale landowners to develop the forest, including wealthy ranchers – fazendeiros – from São Paulo, who received tax incentives to purchase vast tracts of land that had been zoned as extractivist rubber plantations.

The effects can be clearly seen today. We have lost 17% of the Amazon to crop and pastureland just in the last 50 years. This is all within living memory. Many of the older people that we met along the Trans-Amazonian can remember when they started building the Highway, and had their own stories of resettlement, whether as part of INCRA’s colonisation schemes or through voluntary migration.

The sense of time is very acute in the Amazon. I’ve always felt that the problem we have as a species is that we don’t live long enough. If we all lived for 400 years rather than just 80, I think we’d be much more careful about how we live and how we engage with nature and the world around us.

The notion that the Amazon was untouched, pristine and primordial, in need of civilising and subjugating, belies the nature-culture fallacy upon which our way of life, in the West, has been structured.

The separation of nature and culture, the idea that we are somehow above or different from nature, goes all the way back to the Book of Genesis – “Have dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and all the living things that move upon the earth”. An idea partly responsible for climate change and the origin of many centuries of environmental mismanagement, extractive violence, colonialism, subjugation of Indigenous populations, ideas of dominion over the natural world, monoculture, etc.

All of these can be seen playing out in real time along the Trans-Amazonian Highway, where scenes that had unfolded in our own countries (Europe, the United States, Australia) in the past are now transpiring in real life. And, in so many ways, it looks exactly like a Western, replete with notions of the frontier, cowboys, pioneers, and Manifest Destiny.

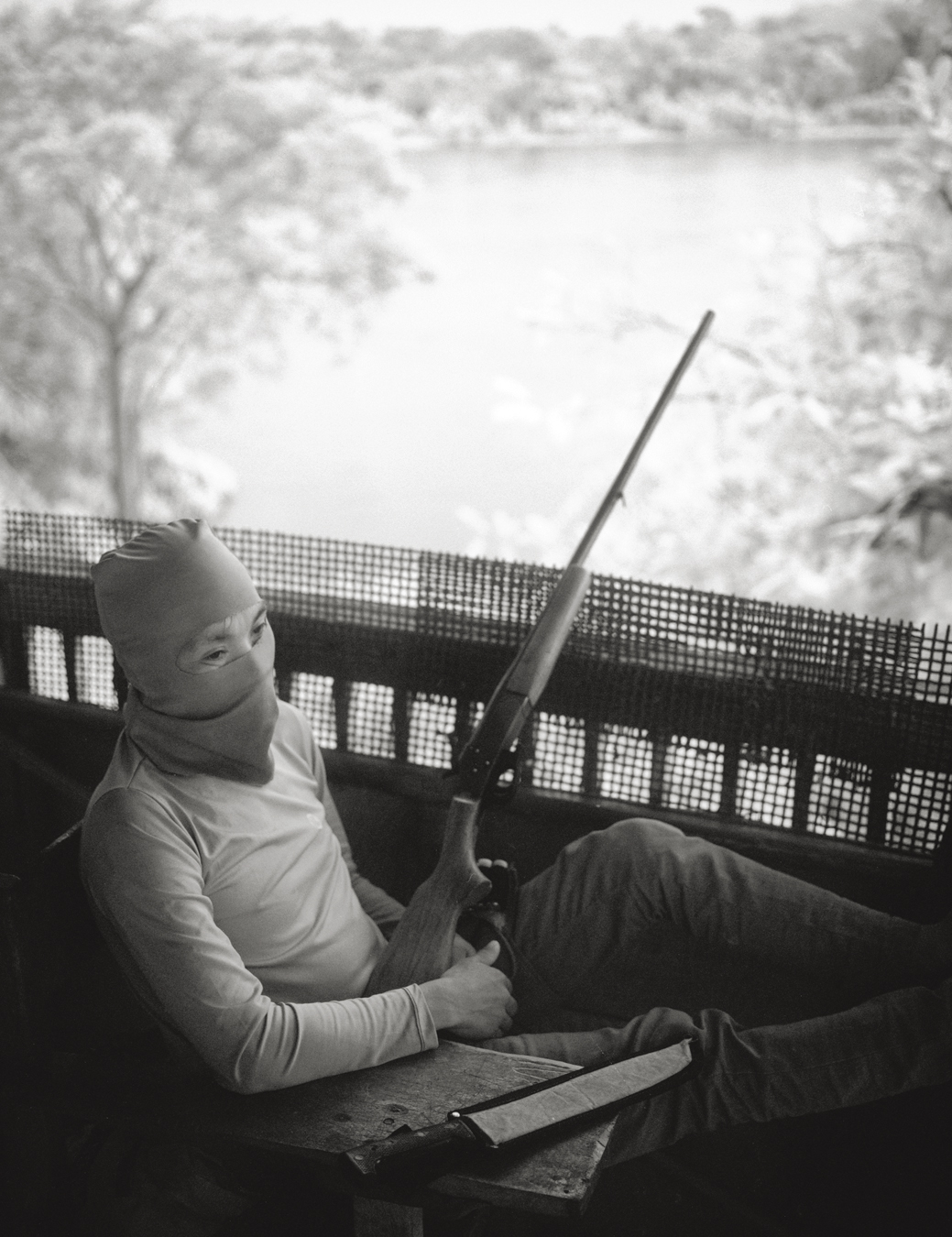

Richard Mosse: Trevor, to shoot Broken Spectre, you hot-rodded a Super 35mm camera and put x2 anamorphic lenses on the front. The result was an extremely wide-angle aspect ratio. It dominates the whole film, obviously, and paired with the black-and-white infrared film, it’s quite specific, right?

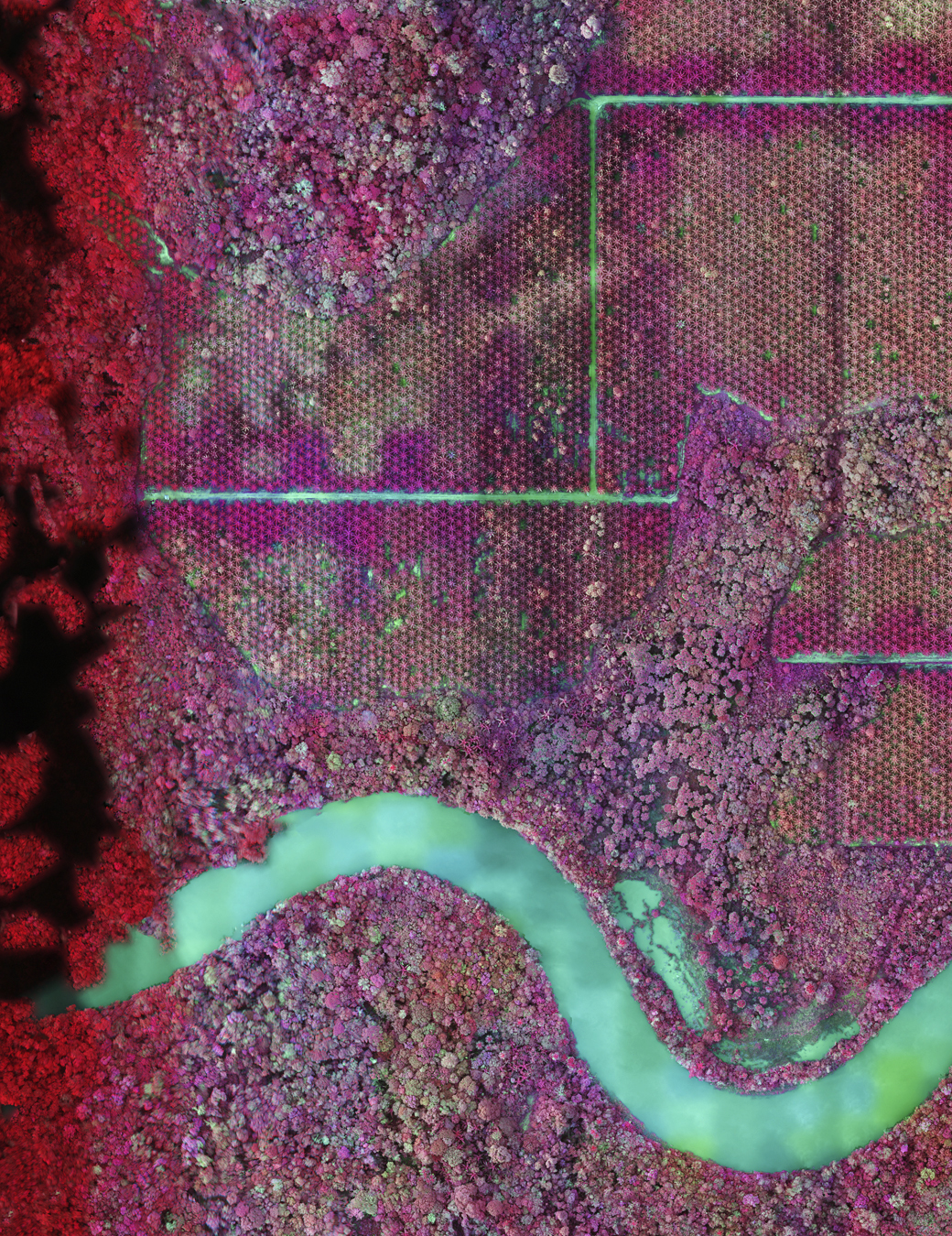

Trevor Tweeten: It’s super specific, and the process was a complete pain in the ass. In fact, every medium that we use is difficult to work with, unwieldy and annoying: the wide-angle with the wide perspective, I guess it was just a hunch. It’s something we’d talked about for a little while and it seemed like it would be interesting to try. Then, when we got to the Amazon I realised it was perfect for the landscape because it’s so flat there. To try to take in that space and create images that feel as if you could just walk into them, it was perfect. With the infrared, there’s something interesting about it in that it feels historical but it also has this strange sci-fi feeling. It takes it out of the present. I think that really works. Infrared is incredible in the way it describes fire and water. Water is there in so much of the process of mining in the Amazon.

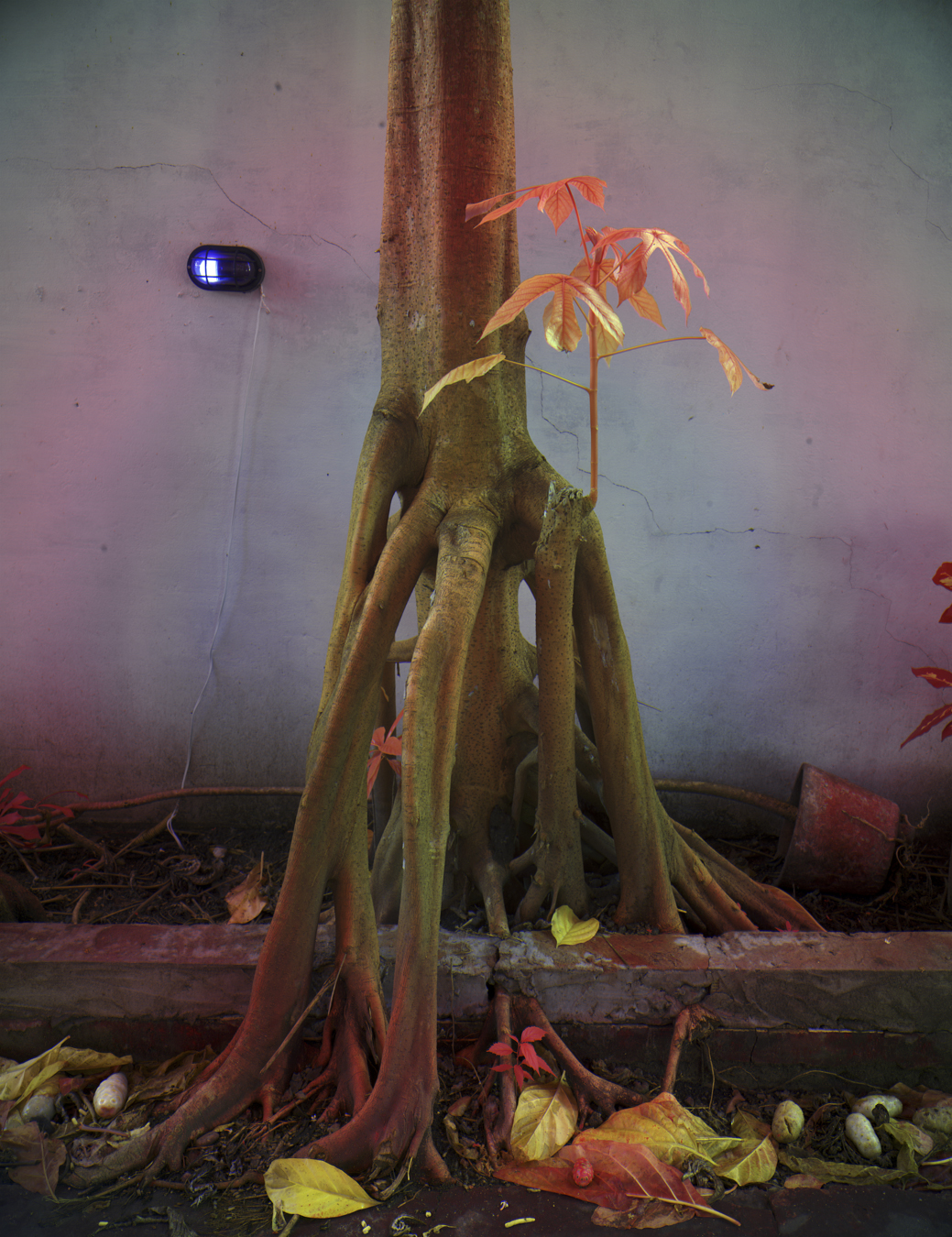

The film’s black and white footage is the human scale — it’s the process, it’s the Western, and it’s all these things that we’re familiar with in a lot of ways. The aerial footage opens this up, so you’re able to see the scale of the destruction that you wouldn’t otherwise. Then, at certain moments, those shots are smashed against micro-landscapes, and you can’t really tell the difference between shots of the vast forest and the camera travelling across the surface of a leaf, looking at little fungi or a tiny spider. These shifts in scale are related to what we were talking about in terms of time.

Richard: Definitely. They’re different temporalities, after all, something that Timothy Morton talks about. If you think of the life of a mosquito, a mosquito lives a very short life, but they live it much quicker than us.

Ben Frost: That’s something I thought about a lot with the ultrasonic recordings. When I’m recording ultra-high frequencies that we can’t hear with the naked ear, I have to pitch the audio down afterwards, which also slows it down. To bring a ten second phrase from a bat down a pitch where it starts to sound human, those couple of seconds can turn into minutes. It often occurred to me, are they saying everything they need to say in that time? And would I need three or four minutes to communicate that same idea?

Richard: I think the black and white film’s artisanal, organic, analogue quality is super important. The grain really speaks to people. Ben, were you trying to channel that with your use of the Nagra, recording audio on 1⁄4” magnetic tape?

Ben: On some level, but also my desire to use the Nagra was born out of a want to synchronise with you guys on a temporal level as opposed to a textural one. Nagra is tape, but it’s incredibly high resolution. It doesn’t feel like an old medium. What’s interesting about working with a tape machine is that it has many of the same issues as working with analogue film: the finite quality of the medium, that it runs out, and that you can’t just shoot everything. The performance of making these shots is something I’ve often really been inspired by. There is this physicality to them and there’s a certain amount of strain and a kind of sacrifice within it. Working with a digital handheld recorder often feels like it carries inherent meaninglessness with it because there’s no risk in it. There’s nothing at stake. As evidenced by the fact that we’ve sacrificed several of those things over the years to the gods of useless technology. Let them die in rivers or bushes or under falling trees or whatever. I just wouldn’t do that with the tape machine because there’s something to the medium. It asks more of me as an artist in that moment.

Trevor: In the challenge of use there’s tension, and out of that tension often comes good solutions and choices in the process of making, as opposed to delaying those choices to the editing process, where so much ends up going in the garbage because there’s too much and it’s overwhelming. Whereas when you’re making choices as you’re shooting or recording, there’s intentionality. We would watch back some of the footage and often it was like it was already edited, the image and sound would accidentally sync up in these incredible ways.

Richard: It’s like some grace occurs through the combination of media.

Ben: There is a performance in listening. Trevor of all people knows about the performance of shooting and what that often demands and requires. This is what John Cage was talking about. When he made 4:33, the idea is that the performance is in the tension of listening in that moment, and the composition is what occurs inside of that space. I think I understood that better after Brazil.

Richard: Trevor, how do you feel about the idea of performance when you shoot? Is that something you relate to?

Trevor: There’s this idea of ‘the zone’ – a place you reach when you’re performing or making something, and you lose yourself in it. When you’re not just rolling and rolling, and you’re having to constantly make choices and really understand what you’re doing because you know that you have only a minute of footage left… I think that is a performance somehow. Then obviously there’s also the physicality of it, with a bigger camera, just navigating the environment, getting yourself into a position to get the shot.

Ben: Maybe the strongest element of this piece is that it feels like direct capture in a way. 75% of the sound for Broken Spectre is unedited field recordings. They’ve been EQ-ed and mastered, but that’s it. It’s about as direct and raw as it could possibly be.

Richard: It’s ironic because I regard myself as a reluctant documentarian insofar as I really resent and hesitate about my chosen genre, about myself, my instincts, my intuitions. The language that I’ve chosen to speak in, I don’t want it, I don’t like it, I don’t respect it. I hate it, I hate myself (laughs). Therefore I have a really hard time making photojournalism, I think it’s a dirty word. This mediated form of storytelling that we’ve come up with by working with surveillance technologies or scientific imaging technologies or whatever, this prismatic way of thinking through the subject using insufferably difficult technologies has liberated me to become the thing that I fear most. In your case, Ben, it is almost the diametrical opposite. Because I think you’ve struggled a bit with criticism of the way you manipulate sound, but that’s what you do, you’re a musician. For some reason, particularly with the work we’ve done together, I feel like you’ve held yourself back and you’ve tried to make something that’s not manipulated. I do wonder whether there is a hierarchy there, whether something that’s unmanipulated has any more worth or value than something that is manipulated. Why is that in your mind, at least?

Ben: What it comes down to is that it’s more challenging. Abstraction is a shortcut, in a way. There’s something harder, and therefore more alluring, about the idea of finding the thing that’s already there and bringing it to light. The search, the challenge of the hunt. It’s harder and therefore, it’s more interesting to me. I don’t know why.

Richard: But that’s very personal because a lot of people listening to the sounds that you produce – they are transparent but they aren’t naturalistic, they’re not manipulated – wouldn’t know the difference.

Ben: I don’t know, maybe you don’t need to know the difference. Maybe you just feel it. Trevor, when you’re shooting, there are so many moments where you’re shooting on Steadicam, and you could be shooting much more easily on a tripod. I think you could make the argument in the same way that people don’t understand, generally, the difference between those two forms of recording, where one is a kind of documentarian gesture versus something that is constructed. I don’t think a lot of people would know specifically that what they’re looking at is a human being carrying around 80 kilos of camera equipment versus a camera that’s sitting on the flatbed of a truck…

Trevor: But the perception is totally different.

Ben: That’s what I’m getting at. You feel it. It feels like that when I watch all the Trevor Tweeten classics from the past ten years, the single shot, moving through a space, navigating an environment. It has this floating quality to it, where it’s more than reality.

Richard: People are sometimes disturbed by it. I think that’s very interesting, because it’s simply an optic floating through space, slightly more smoothly than the human eye. Why do you think that is?

Trevor: There’s a first-person quality to it that has a short- circuiting effect. You end up feeling like you’re directly in that space. As the camera moves through space, you get caught up in a different way – especially when it’s sound and picture working together, it can take you over. I’ve always been interested in connecting space. I think there’s a time and place for editing and I think there’s people that make amazing things through edits…

Ben: I find it really interesting that you now have this relationship with dance in your current work.

Trevor: That’s the same thing – dance can look bad when it’s on film. But when it’s continuous, when there’s a single take and there’s movement, the camera becomes a dance, too, and you create a totally different kind of experience. I find a huge amount of pleasure in making that happen. In documentary, there’s something I find interesting about seeing a space and thinking about how one could move through it and connect all these dots in a way that the viewer is constantly gaining information. Sometimes it can be surprising, there’s the grand reveal, or you start at the end and work your way back to the beginning, so that the viewer has to put two and two together. Then you add multi-screen to that, and you’re having to add two and two and then four over here. Then you put mediums together on top of that, and all of a sudden, you’ve got something where you’re asking a lot of the viewer. But I think more and more viewers are quite capable of doing that. People are very visually literate now. They aren’t just watching TV, they’re watching TV and looking at their phones, they’re watching all these things and then smashing them all together. People are very capable of keeping up visually. I think it’s very exciting.

Ben: Richard, you’ve just been back to Brazil shooting these images of the domestic lives of middle class people in Brazil, in their homes, where some of these plants, which are being wilfully exterminated in the forest, are now being purchased in Ikea and put in terracotta pots and sat on windowsills. It’s really fascinating to me. I guess my question is, are you done with this chapter now? Is that it for you or do you feel that there is more to mine?

Richard: Yes, I think I might go back again to finish these eccentric portraits of Amazonian pot plants. It’s been fascinating, being invited into people’s homes and studios to photograph their plants, seeing how they live with them, how proud they are of them, how much they mean to each person, and in such different ways. It was just an impulse, this sister project, but it’s right on the pressure point of the nature-culture fallacy, revealing how humans project desire and belief onto the natural world and incorporate it into their everyday lives. But I do wonder if I’ve explored infrared quite enough at this point.

Trevor: Richard, I’m curious – do you think that these mediums are a shortcut? Getting back to what Ben was saying, about how he relates to the different processes, analogue and digital, how do you see how these work for you? Manipulation versus the raw object and how manipulation is almost a shortcut. How do you feel about your chosen medium, infrared and all?

Richard: As you said yourself, it’s extremely difficult to achieve some of the results that we’ve produced over the years. The last twelve or fifteen years have been logistically and technically very frustrating and full of challenges on every level in terms of getting an image at all a lot of the time. There’s a certain alchemy there. For me, that’s very liberating. I’ve deliberately chosen imaging technologies that hold some agency in the subject we’re attempting to represent, so each media we employ helps foreground and unpack hidden aspects of the stories that we tell, not just for ourselves but also for the viewer. That has the extraordinary effect of activating, for me, the scenes that we capture. There’s no way in hell that I would have taken a lot of these pictures if I was using a conventional medium. But for some reason, because they’re ecstatic – to use Werner Herzog’s term – I allow myself to take them, by going on this infrared herring. The lengths we’ve gone to are almost masochistic.

I was talking to Felix Davey, another Irish artist, about this, and he’s convinced that Irish artists generally have a tendency towards masochism in terms of Christ dragging the cross through the streets of Jerusalem before he was crucified. That sounds a bit like us with our beer coolers full of infrared film in the middle of the Congolese war zone. So it’s not at all a short cut, but maybe it’s a short circuit. An aggravated documentary form.

Ben: I wonder if that’s maybe the common thread actually.

Richard: The masochism? (laughter)

Ben: Yes.

Richard: We’re setting ourselves up for games, in a way. I think Brian Eno realised that you sometimes need rules to make better art. What Trevor was talking about earlier – how having a finite amount of film helps you speak more carefully – that’s just another rule in the end. All those things stack up to help you be a better artist, at least in your mind. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter what other people think. Ultimately, you have a conversation with yourself in order to make the work, and to get out of bed in the morning. Whatever motivates you to do that is worth exploring because otherwise it wouldn’t get made, simply. (laughs)

Ben: For sure.

Trevor: What I’ve always found exciting about the processes that we’ve put ourselves through with each new medium, is that there’s a new language. Not only a new visual language, but also just working with the camera itself and what it wants to do and listening to that. I think that was always the most rewarding part of all these things: learning that new code and then really diving into it and finding it, and then being able to see that in the world and how it would work with the subject.

Richard: It’s about creating new symbolic orders each time, suitable not only to the medium, but to the subject, finding that neat dovetail between them and then creating a whole new language around it. It’s very particular.

Trevor: Maybe that’s also why we’re able to listen in a way that perhaps we normally wouldn’t have. I think if we weren’t learning about the technologies at the same time as being in the space, maybe we wouldn’t have listened to the material, to the subject, as much. Maybe, because we’re learning as we’re making, we were listening better?

Credits

Images courtesy of Richard Mosse

Broken Spectre was co-commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria, VIA Art Fund, the Westridge Foundation, and the Serpentine Galleries

Additional support was provided by Collection SVPL and Jack Shainman Gallery

Broken Spectre by Richard Mosse is published by Loose Joints in collaboration with 180 Studios and Converge 45