Each year in late February, millions of people take to the streets of Rio de Janeiro for five days of nonstop partying. The collective mood is one of euphoria. At the centre of Rio Carnival, after all, are its colourful parades and “blocos”; all feathers, floats and sound systems. But away from the world’s biggest street party, you’ll find a series of more intimate but no less chaotic affairs: the carnival balls. Now back in full flow after a pandemic pause, 2023’s instalment – arriving in a hopeful, post-Bolsonaro time of political change – gave revellers all the more reason to celebrate as they claim a different future for themselves.

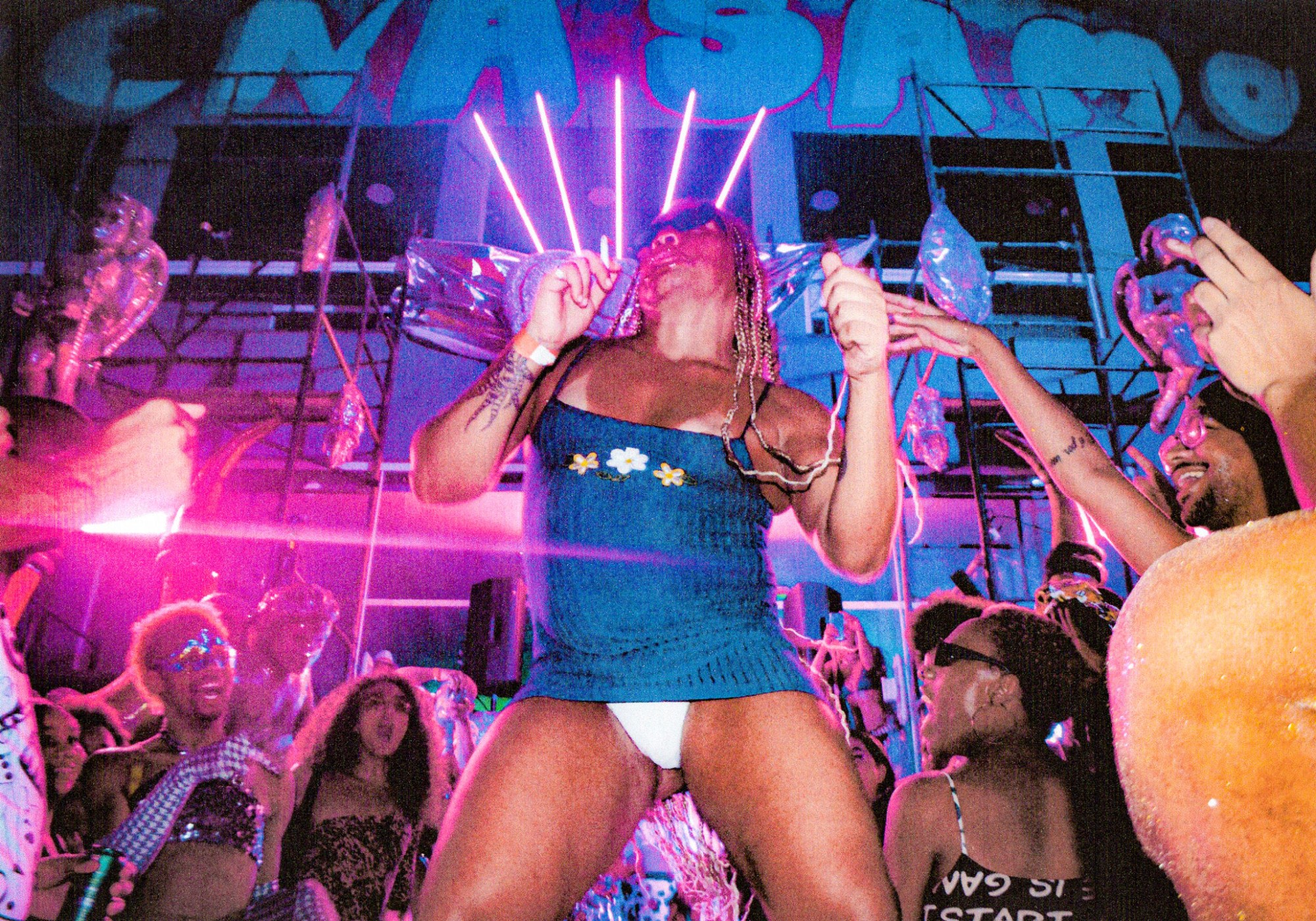

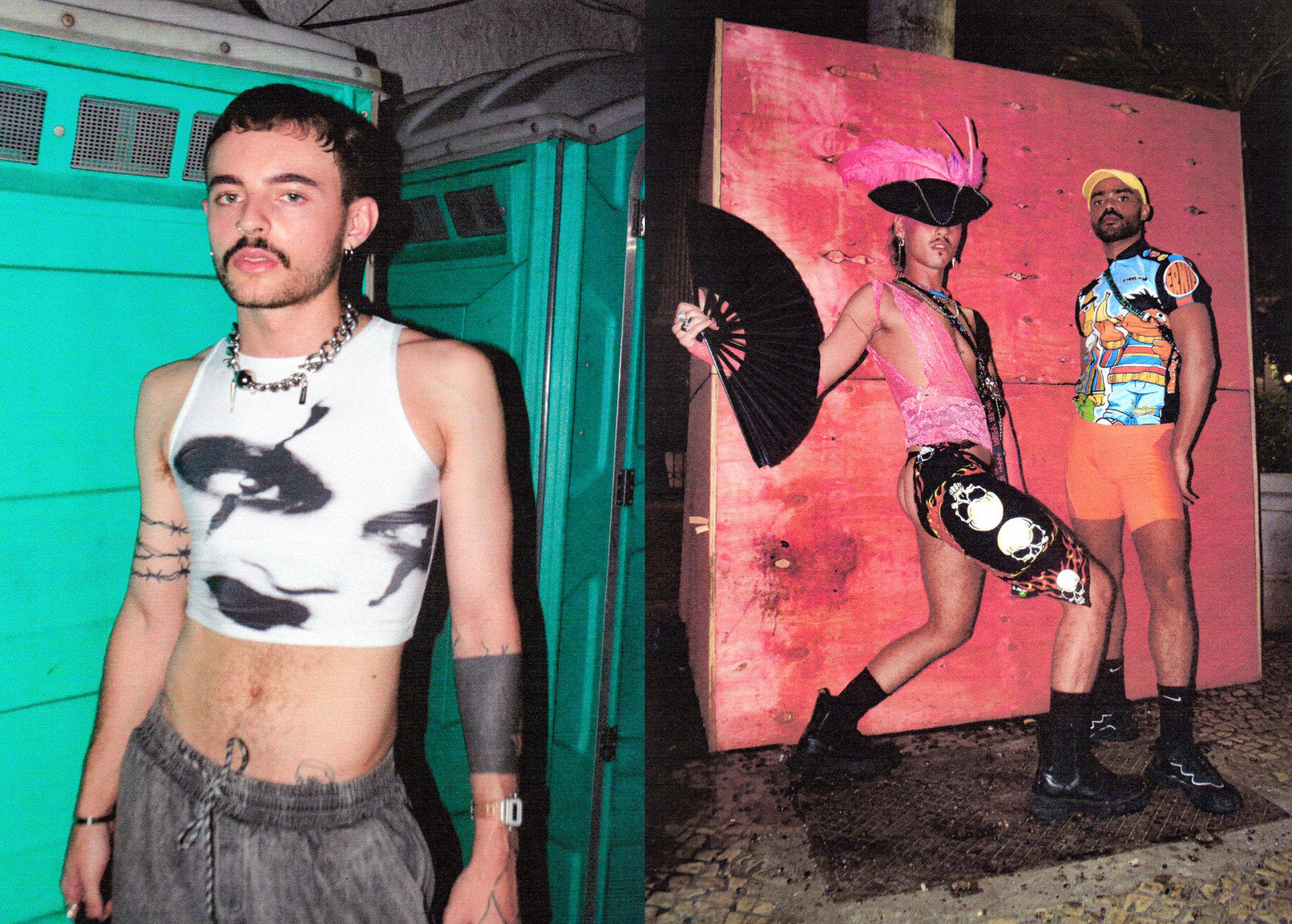

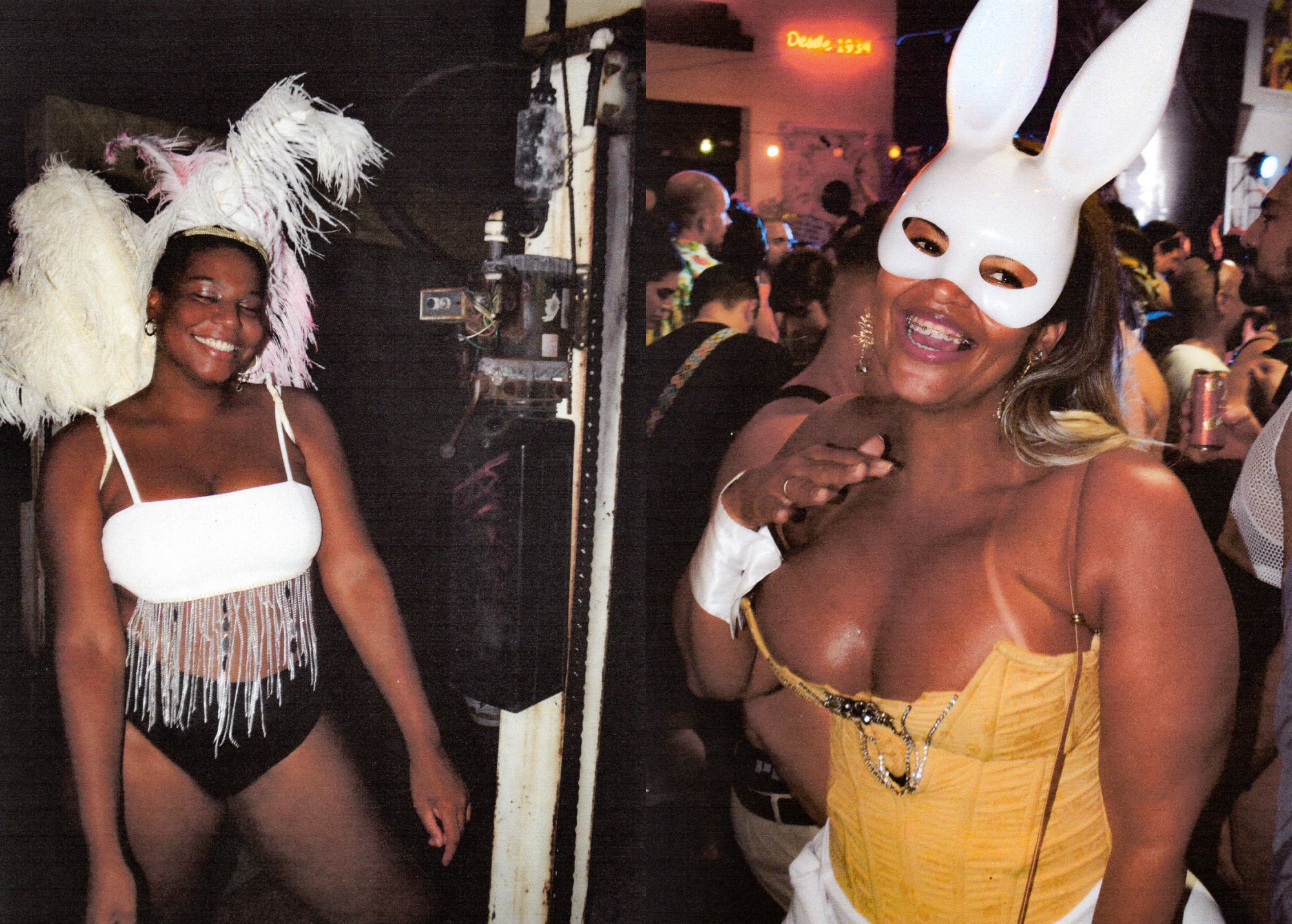

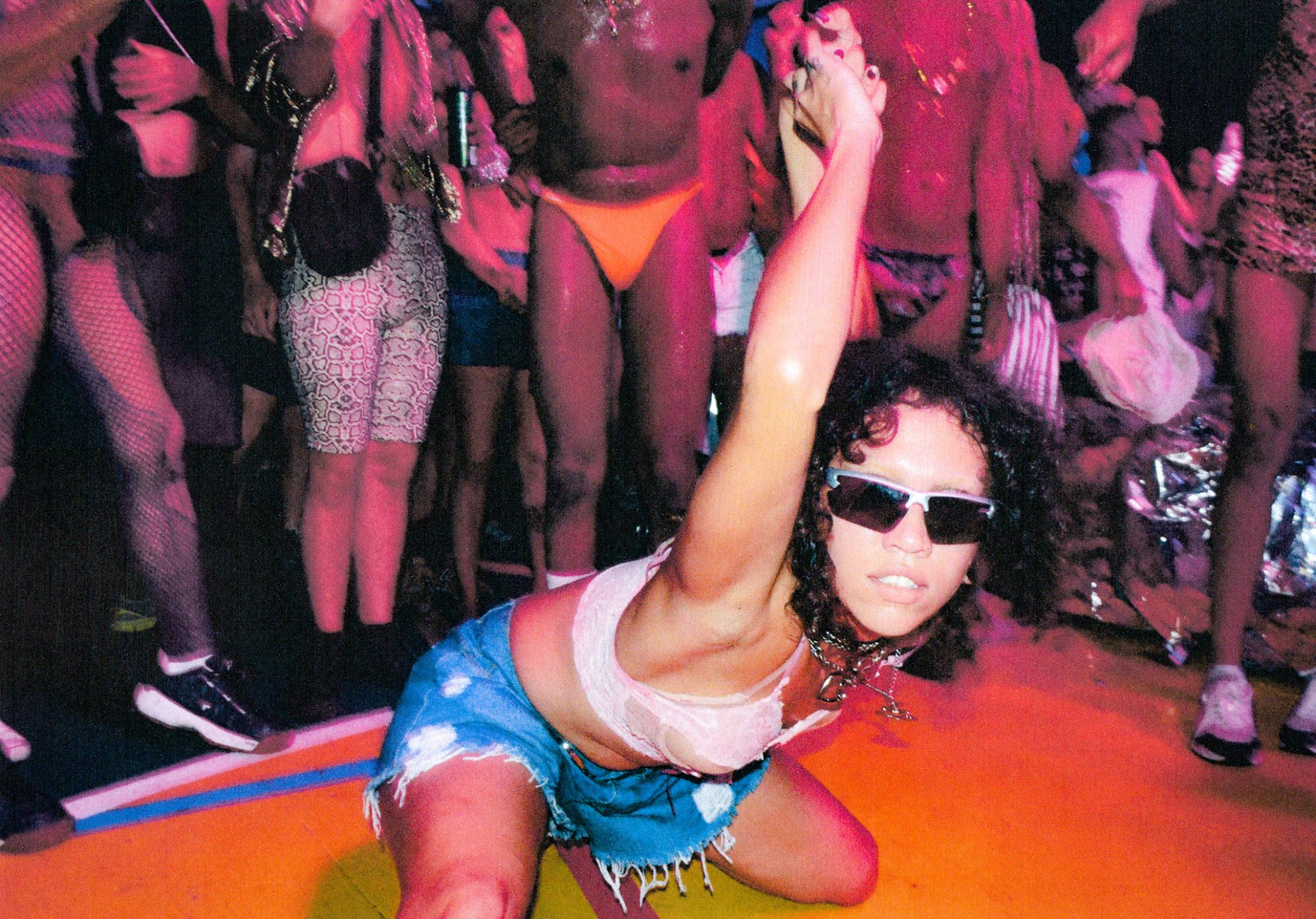

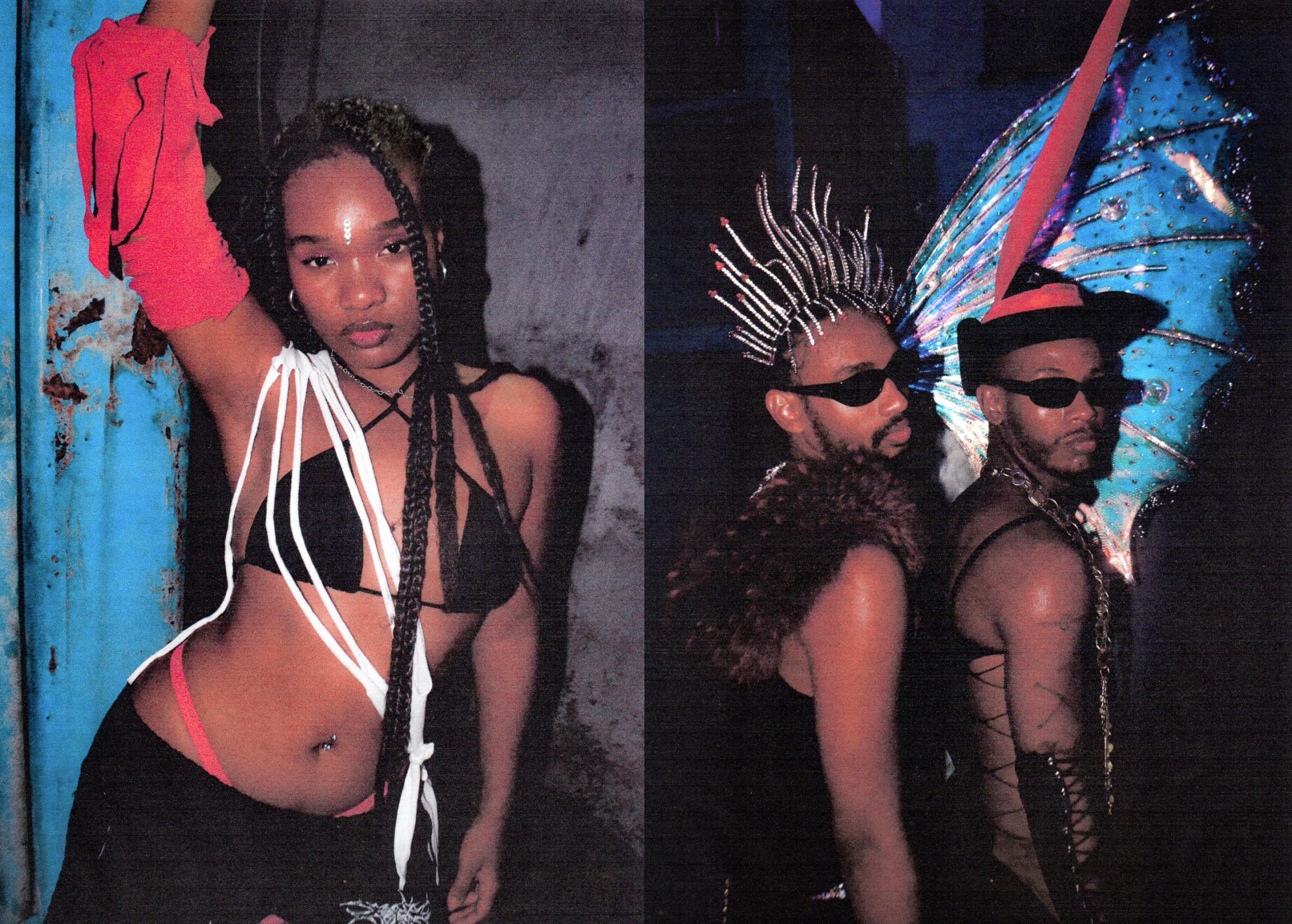

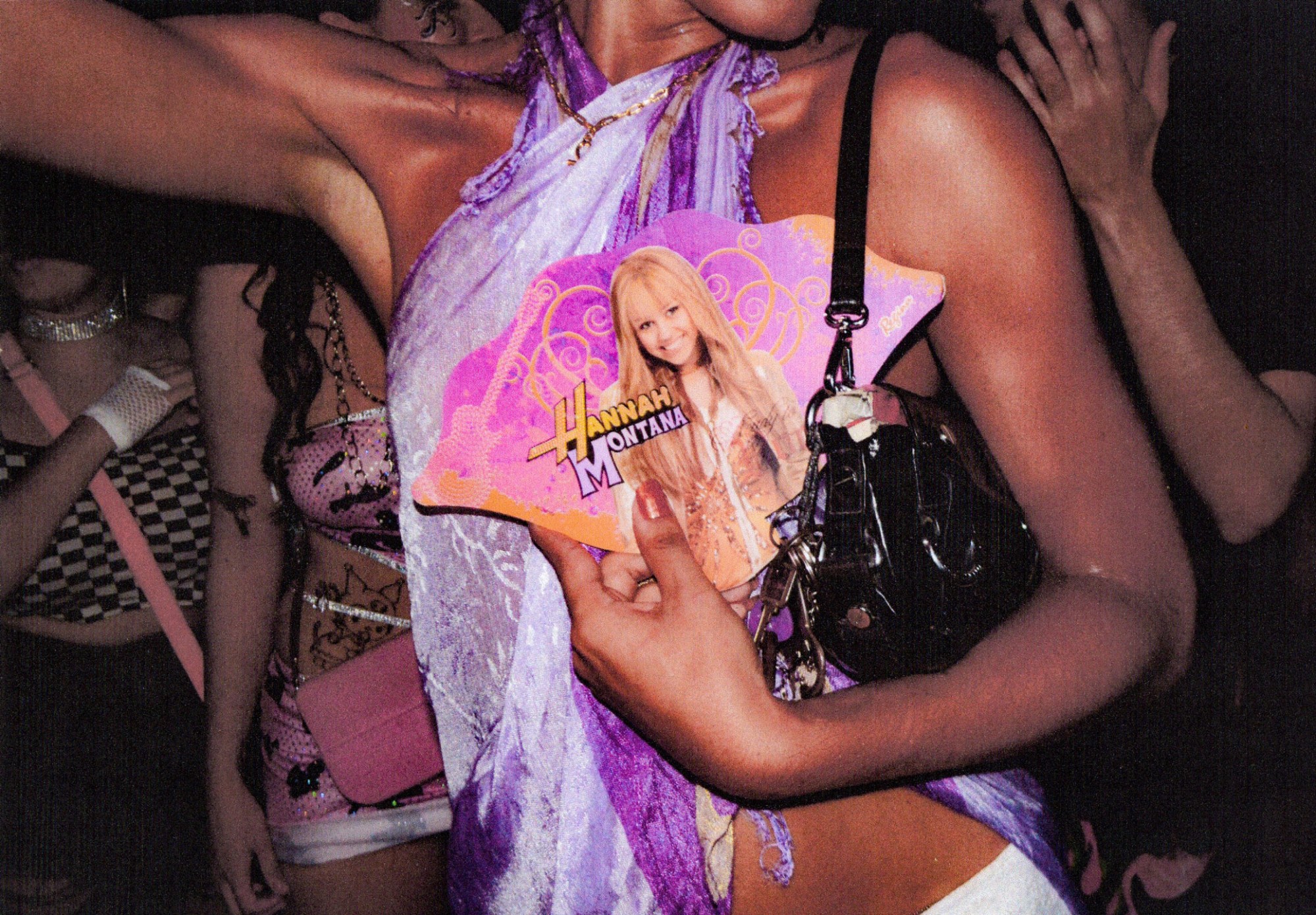

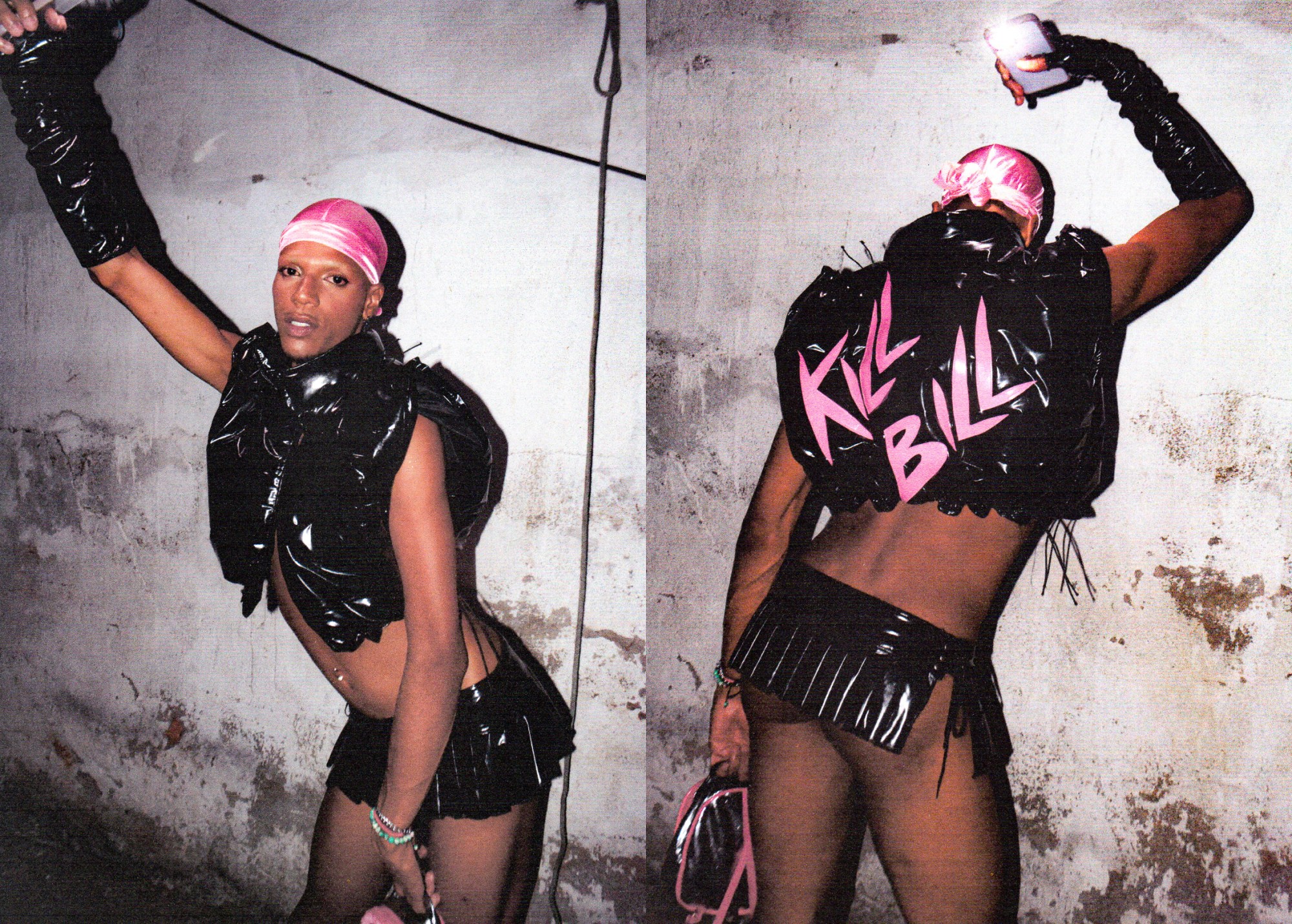

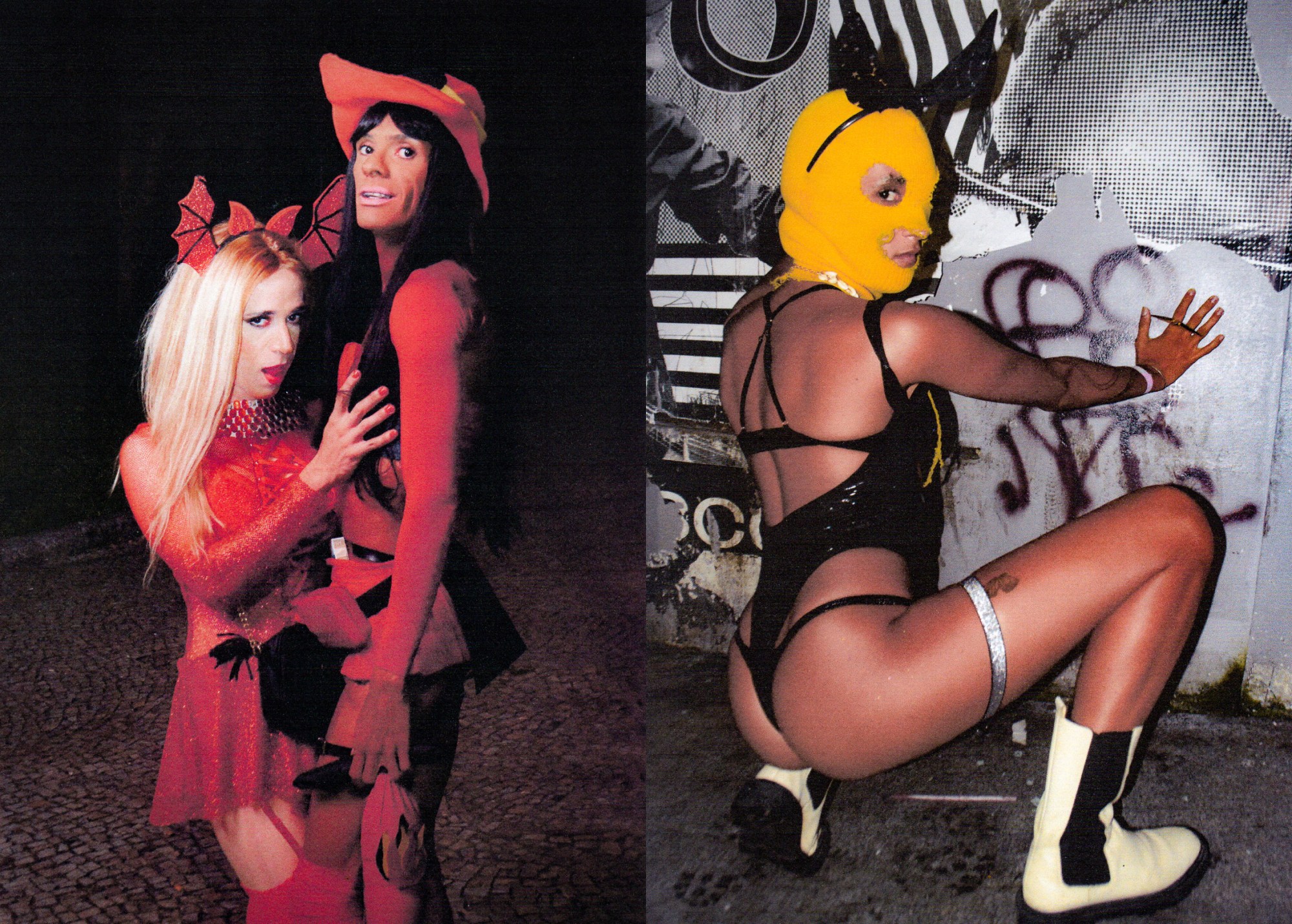

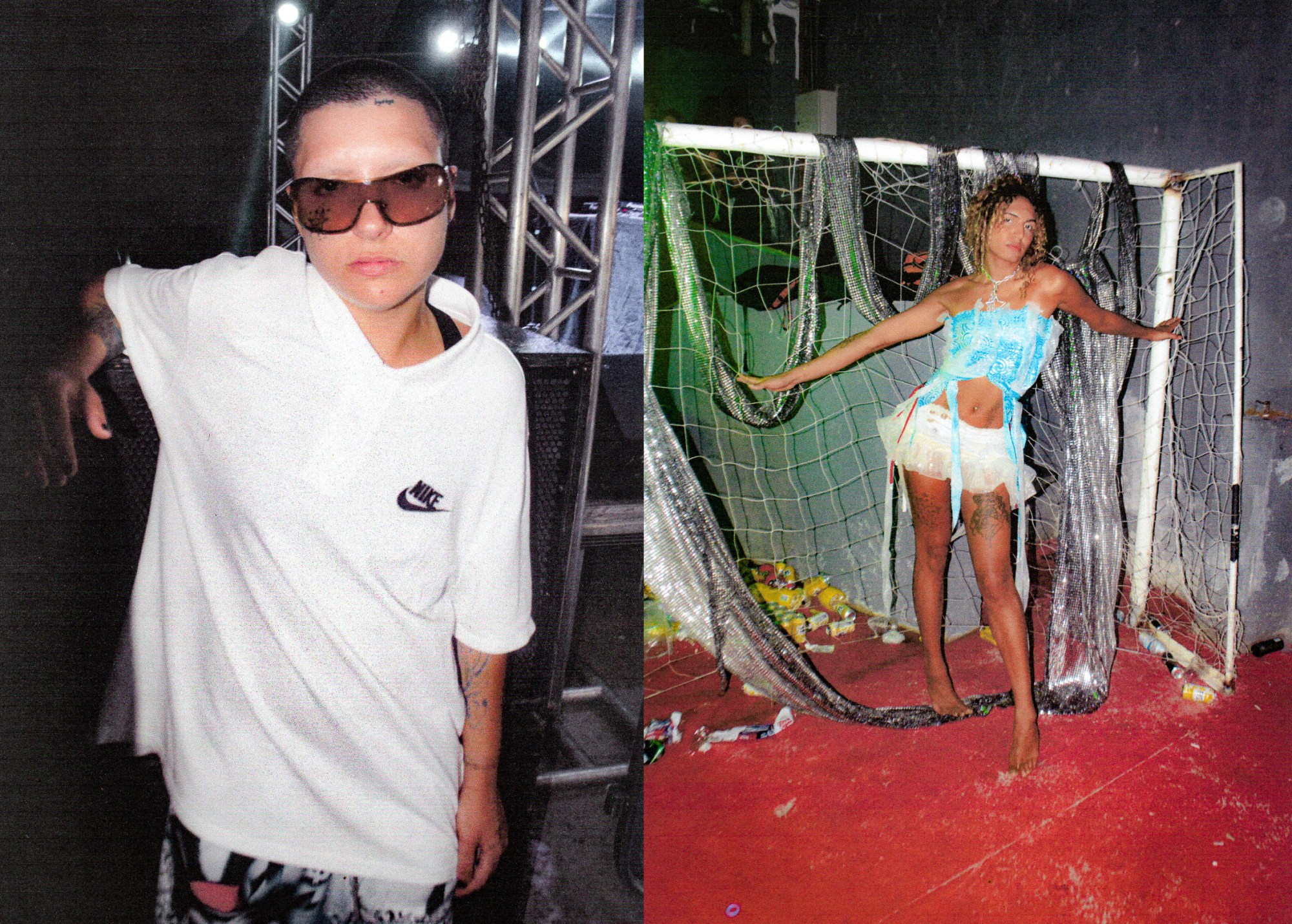

“Excess is what sets the tone; an excess of people and of enthusiasm,” says Miguel Arcanjo, a producer, DJ and member of the city’s Escola de Mistérios collective of musicians and creatives. “Producing an event during carnival means dealing with high expectations from the public.” Parties such as theirs, as well as those by Mariwô (who platform young, Black LGBTQ electronic musicians), Lâmina (a hyperpop, house and techno night) and Kode (queer-friendly, bass-heavy) are leading the way as vanguards of Rio’s alternative carnival scene; taking over warehouses, car parks and other vast spaces in the city’s Port district.

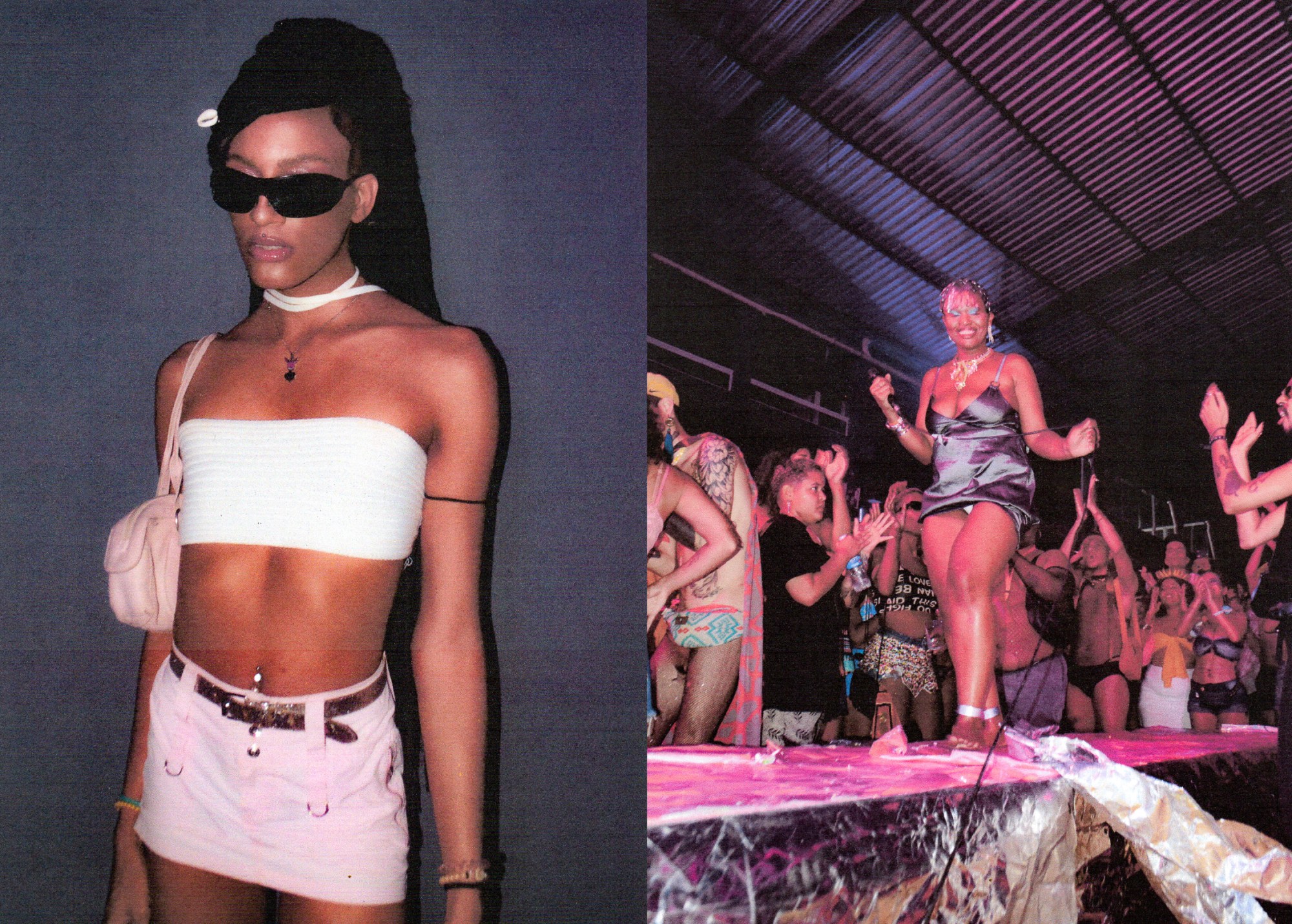

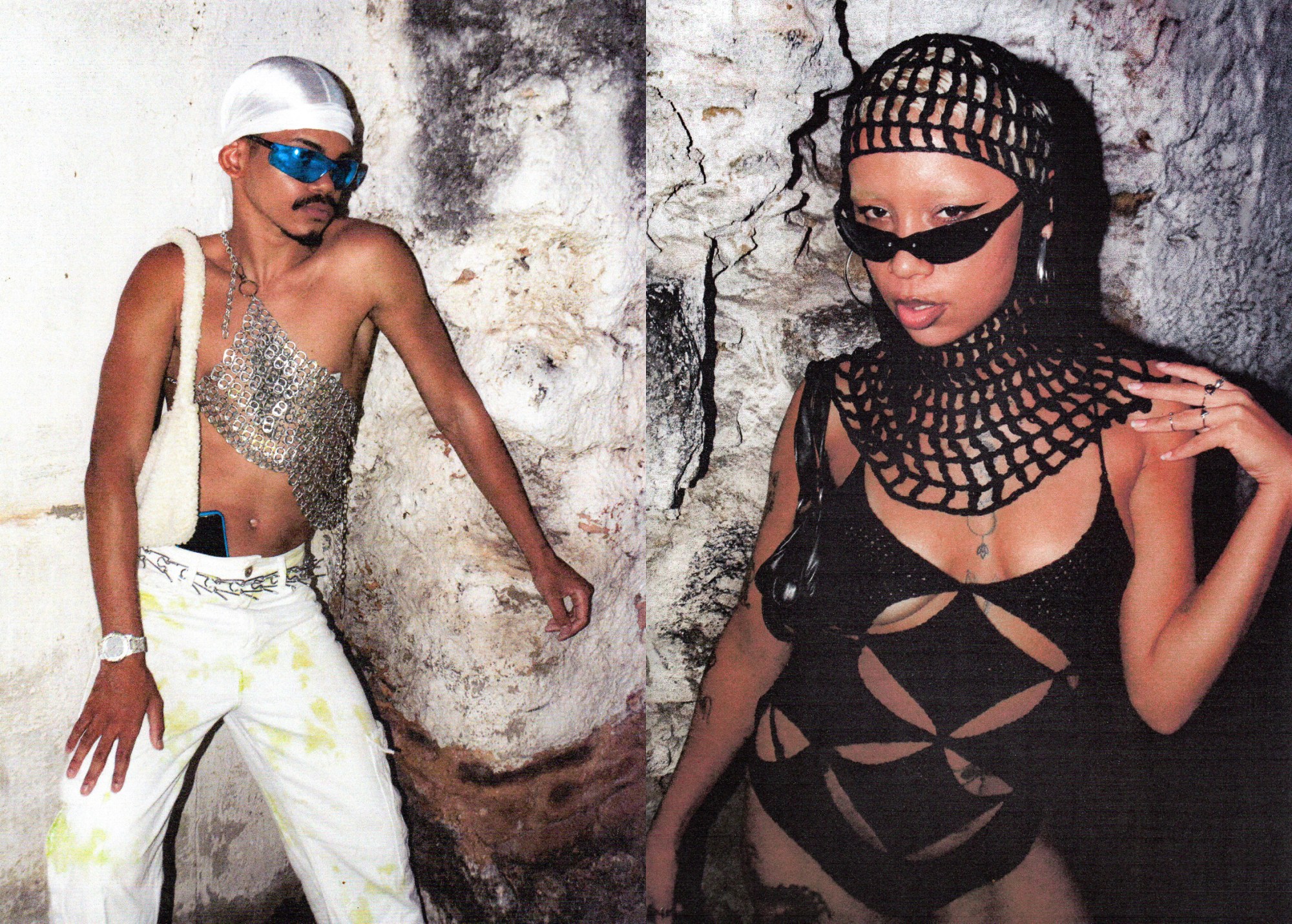

Historically known as “Little Africa” due to its ties to the Afro-Brazilian community following the national outlaw of the slave trade in 1831, this neighbourhood is an apt setting for these decolonised carnival dreamscapes (carnival was introduced to Brazil by Portuguese colonisers in the 16th century, then embraced by a Black population struggling against oppression in the post-abolition period) to flourish. Today, thanks to these underground events – which provide an alternative to the mainstream circuit of parties with expensive tickets and largely white, upper-middle-class crowds – the practice has been reclaimed to generate income circulation to local Black and LGBTQ communities.

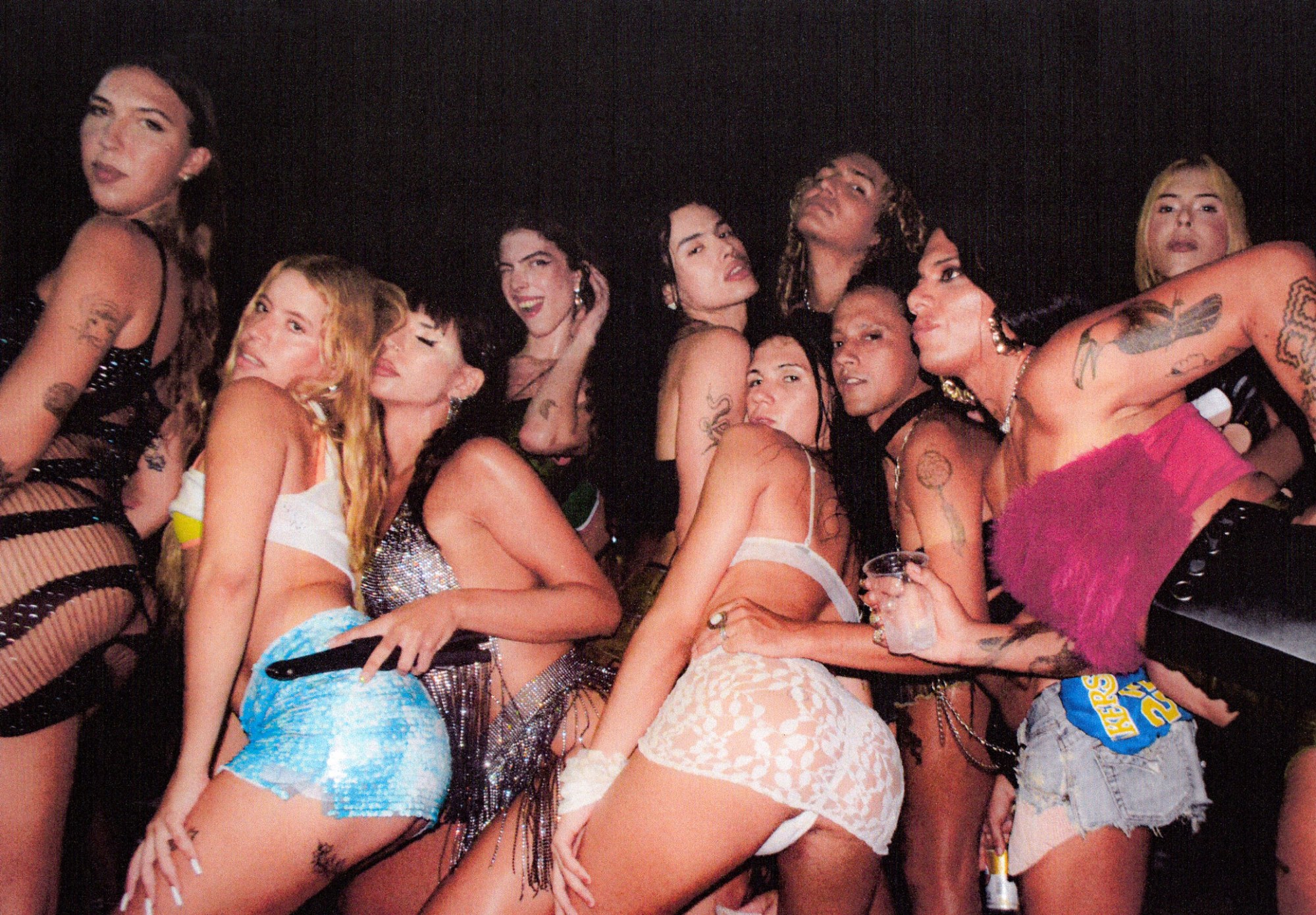

“The work we do is very much linked to our connections in the city,” Caique Cerqueira, co-founder and exec producer of Mariwô, tells us. “From location to set, it’s one big challenge to build an ideal, unreal place with the spirit of the street as our greatest inspiration.” This year, Mariwô’s carnival ball (their fifth) provided safety and liberation; a space to feel part of something bigger than yourself. At the forefront of urban culture and fashion in Rio, the collective represent the contemporary African diaspora in a city with shockingly high rates of violence towards marginalised communities. These balls, then, are integral in ensuring everyone is represented and celebrated – something which is sadly not always the reality in carnival.

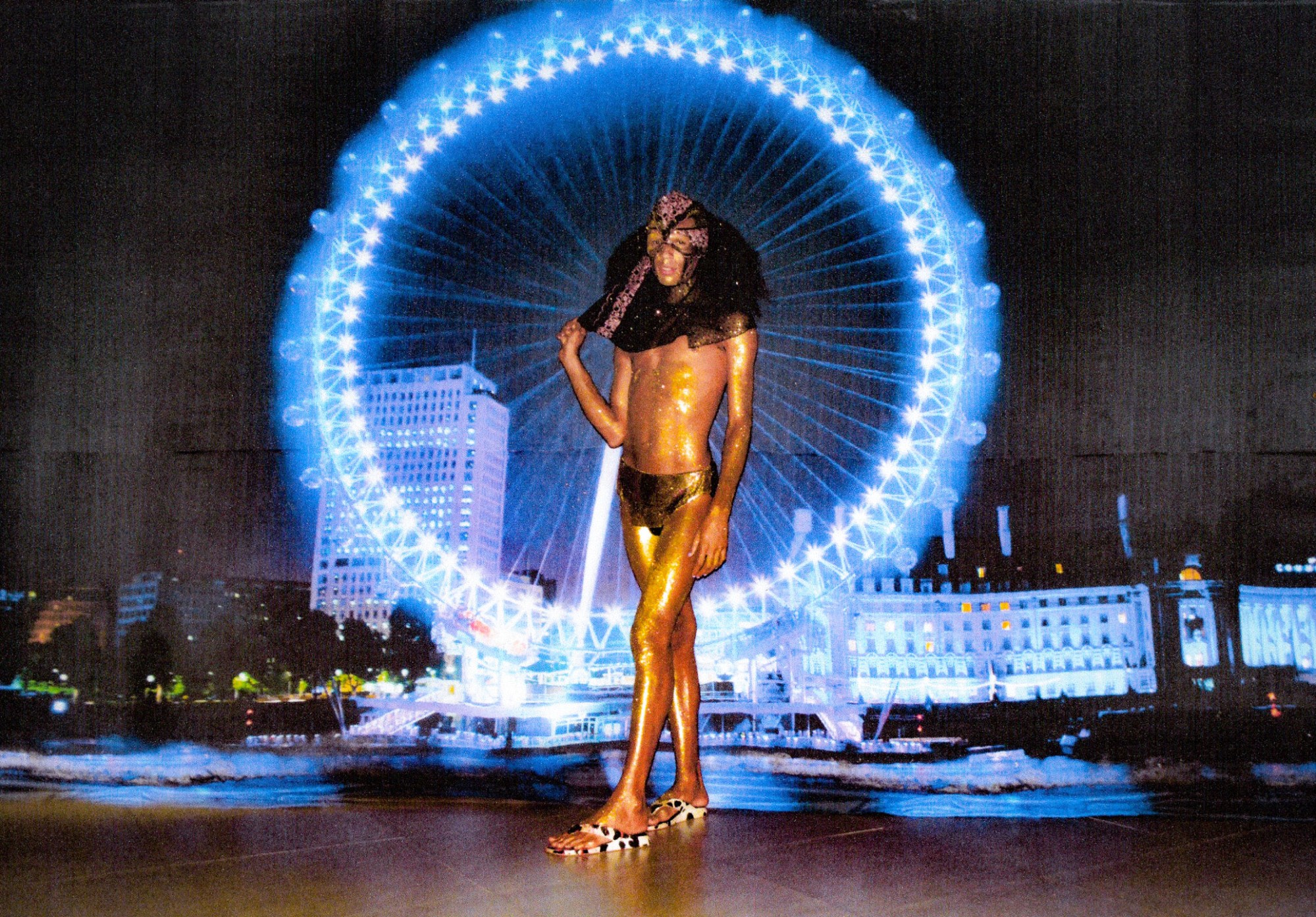

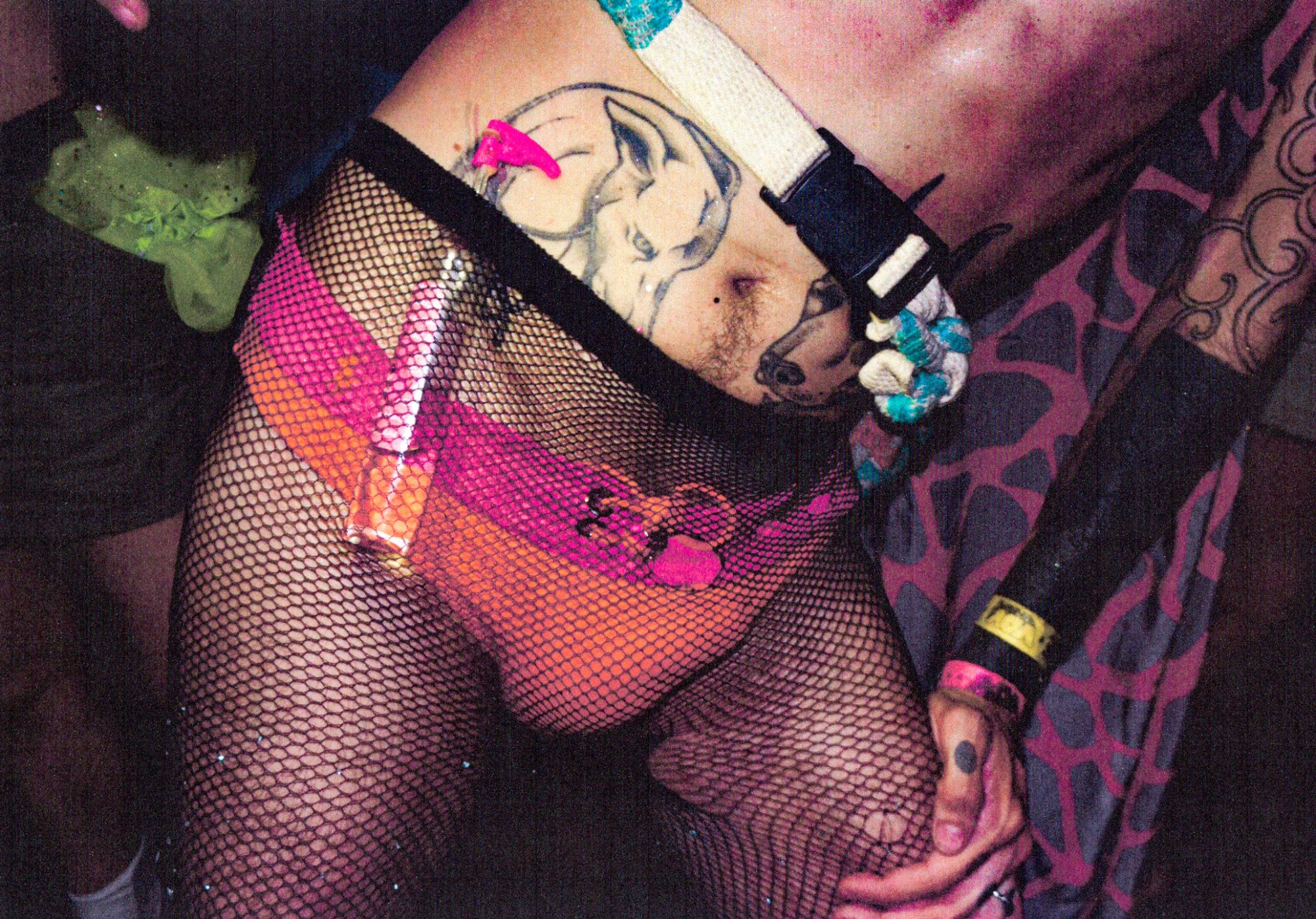

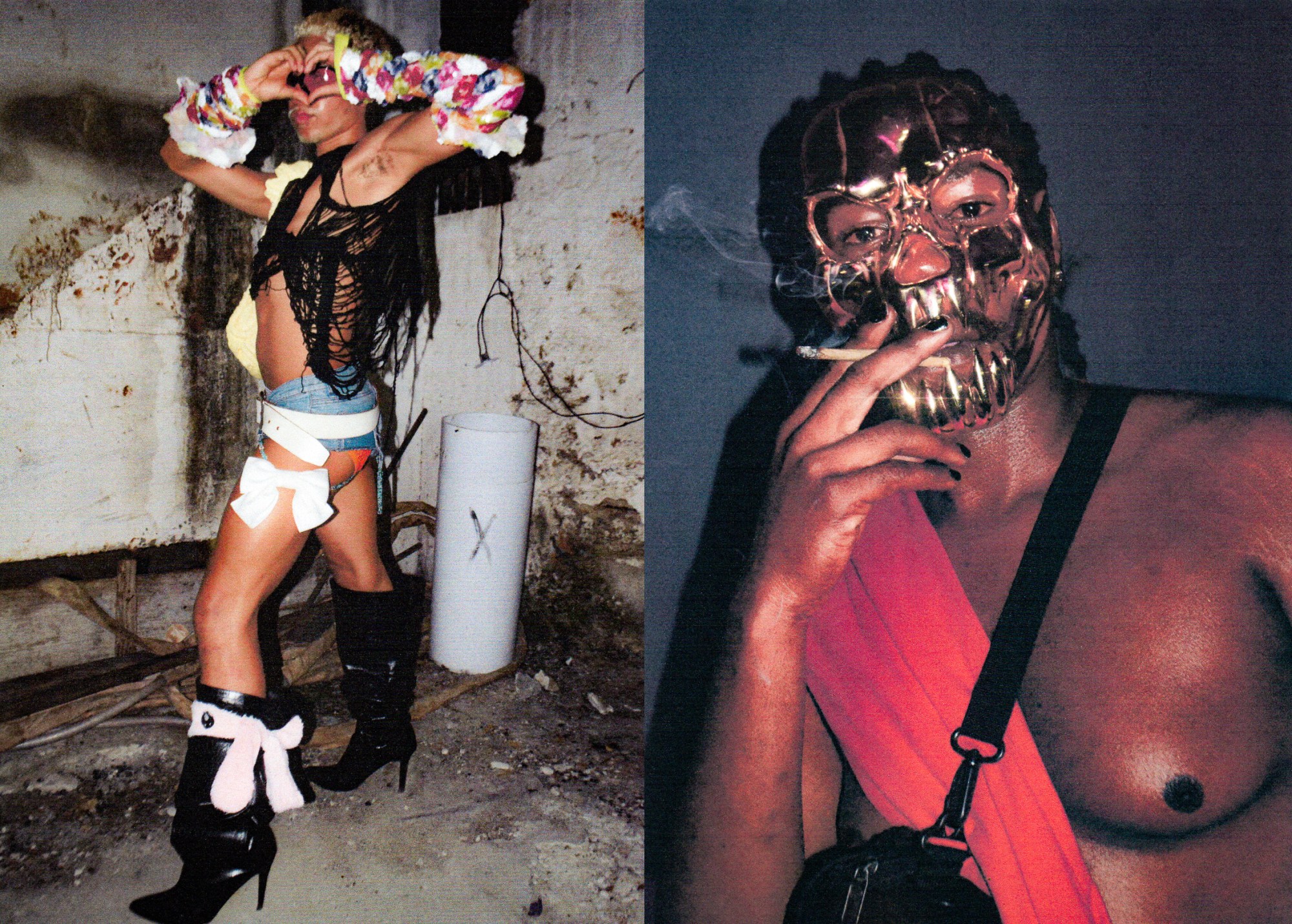

Event curation across this scene is invariably focused on inclusivity and trans protagonism, with DJs like GLAU, Evehive, Pambelli and Cuca making for memorable dancefloor moments on the aforementioned lineups. While Carioca funk is the sonic blueprint of Rio Carnival proper, the sound of these parties is an eclectic mix of global electronic references. Members of local “kiki houses” – House of Cosmos, Cazul, Bushido, Aláfia, Dandara, Mamba Negra and Lafond – were a familiar sight in attendance, whether there to perform or party. The Rio Ballroom scene has, of course, established itself as a central part of the underground cultural movement during carnival season and beyond. The city’s music scene too, showed up via performances from artists such as EBONY and Frekwéncia, who moved the crowd at Lamina and Mariwô respectively, connecting to the audience through queer and Afro-diasporic narratives. “Carnival parties are moments where we can step away from our troubles and enjoy the night; people from different cultures uniting as friends,” says Asafe Malafaia, DJ and producer of Lâmina.

During the pandemic, Brazil has faced a scenario of uncertainty, fear and lack of prospects, something only intensified by the detached stance of a government led by the former president Jair Messias Bolsonaro. These crises have had a direct impact on nightlife industries, leaving the organisers of independent club nights to increasingly take on the role of social militancy; defending the right to access culture. “Producing a party is to provide a space for bodies to meet and be welcomed in their utopias, joys and beauties,” says Mariwô’s Alex Gabriel. “Carnival is the portal and we just want to be free and happy. It’s one big negotiation between the body and the city; between flesh and asphalt.”

With last year’s victory of the progressive government led by President Lula, the country is beginning to experience a collective hopefulness. The return of carnival represents the celebration of the country’s democracy and cultural diversity, which were devalued by previous leaders. It’s a moment for Brazilian people to express themselves and rediscover their cultural identity. “Now that all eyes are on the city, we’re celebrating and consciously overcoming those dark years – the end of both a pandemic peak and of a president who never represented us,” says André Suisso of Kode. “Being able to live this freedom is inspiring in so many ways.”

Credits

Photography Igor Furtado