With 20,000 Days on Earth they explore a different facet of the reconstruction of a ‘moment’, by restaging a fictional day-in-the-life of the Australian post-punk rocker Nick Cave. Cave appears as a living, breathing stand-in for the universality of the working artist- on this, his 20,000th day on earth. “The reconstruction and re-enactment projects we’ve done in the past taught us a lot about how to use artifice to create an authentic moment, and that really helped us reach for the emotional truths we were seeking in this film, without being dragged down by the biographical facts”, they tell me.

“Over 35 years Nick has created the thing that he is, and it’s not something he switches off when he walks off stage. The myths form a far greater part of the story than anything that might be revealed by seeing Nick in the supermarket or driving his kids to school. In that respect, the truth doesn’t matter.”

The film, a hybrid documentary/ concert film, is an elegy to the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll and creation. Films like Jean-Luc Godard’s Rolling Stones film Sympathy For The Devil, The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night and Led Zepellin’s The Song Remains The Same acted as inspiration: “those films felt like they were in some way reaching for something greater.” Generally, rock documentaries seek to uncover the secrets behind the image, but 20,000 Days never goes into the sensational details of Cave’s junkie past and famous lovers. “Our contention is that with artists like Nick, there really isn’t anything to peel away,” they explain. “Over 35 years Nick has created the thing that he is, and it’s not something he switches off when he walks off stage. The myths form a far greater part of the story than anything that might be revealed by seeing Nick in the supermarket or driving his kids to school. In that respect, the truth doesn’t matter.”

And yet truth and authenticity are always bubbling away in the background of the film. The importance of self-expression, and the potential of art to create alternate universes in which to escape to, are key drives. In one scene, Cave praises simply the process of collaboration, in a manner which seems to reference the artistic practise of the film’s creators. “We began working together in our second year at art school, so we’ve really never known any different,” they tell me. “A lot of creative partnerships seem to come about by combining skills, but we met when we were 20, and didn’t really have any skills to speak of. So we’ve learnt everything together. It’s impossible now to imagine working any other way – the thing that collaboration does more than anything for us is that it creates dialogue. Every idea, however small, is instantly put under scrutiny. If you believe in something, you have to fight for it. Not being precious about ideas gives you an incredible freedom, the ego of self doesn’t get in the way.

“Nick was up for trying pretty much anything. We always said that if a particular idea didn’t work, we’d walk away from it, so that really gave Nick the freedom to try all sorts of things… That trust and friendship is really what this film is built on, without it, we simply couldn’t have made it.”

Crucially, Iain and Jane’s work straddles both the closeted nature of the art world, and the populist world of music videos (for artists such as Scott Walker and Gil Scott-Heron) and the rock documentary. “It was a completely concious decision. We were at Goldsmiths in the mid-90s, and in many ways it was an incredible time to be there, but you were in no doubt that you were in the wake of something. The YBA explosion had created this idea that art school could be a fast-track to a career as a superstar artist.” Artists around them appeared obsessed with producing work “on a museum-scale, these huge shiny things, but with no real substance”, name-dropping philosophers, or “trying to intellectually prop up these hollow gestures”. At the same time, many of their friends were deeply involved with music culture, and were putting on gigs, running clubs, producing fanzines and putting out records. “We loved the way that music engaged directly with an audience, that you could go to see a band and literally see, hear and feel the emotional connection it’s able to make. We wanted to make art that could do that.”

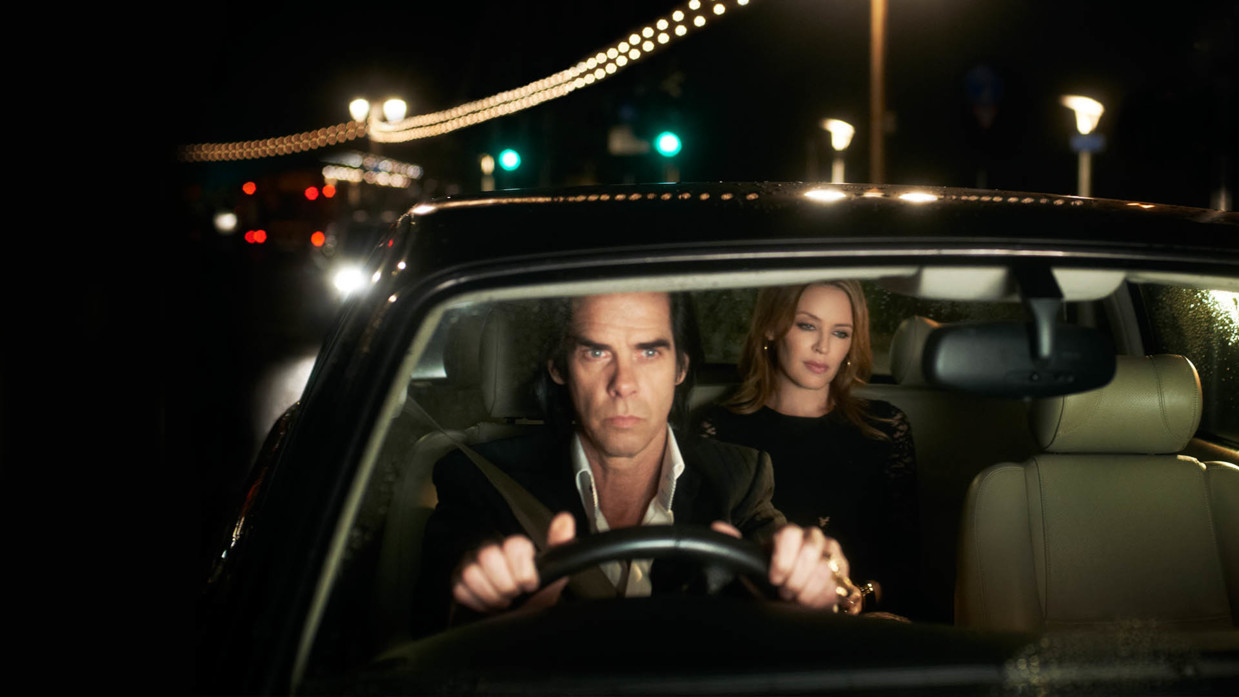

“The car is like a psychological bubble, we thought of it like the inside of Nick’s head, so it felt entirely possible for characters to appear and disappear without any word of explanation.”

Strange cameos introduce us to key characters from Cave’s past, who appear like Dickensian ghosts of rock ‘n’ roll past. Kylie Minogue, Ray Winstone, and Blixa Bargeld appear as spectral presences in the rear window of Cave’s car, to ruminate on the shared creative journey. “These scenes were about a few different things,” they explain. “One of the key ideas was about wanting to find ways to explore different sides of Nick’s character. Like all of us, Nick changes according to the people around him. His relationship with Kylie manifests very differently than how he interacts with Ray Winstone, for example. We felt that with many documentaries you feel the subject is engaged in a singular dialogue, either with a presenter or the filmmaker. The car is like a psychological bubble, we thought of it like the inside of Nick’s head, so it felt entirely possible for characters to appear and disappear without any word of explanation.”

The psychoanalyst (and massive Cave fan) Darian Leader also makes an appearance, in order to interrogate Cave on his black leather couch. Iain and Jane had known Darian for about ten years, and hoped that a conversation in him would probe deeper than the journalistic inquiries that Cave is so notoriously wary of. “Nick and Darian met for the first time as the cameras were rolling and they sat down to talk. We shot for about ten hours over two days. It’s not true that the cameras ever had to stop rolling.”

The archive, a touchstone of Iain and Jane’s work, is here literalised as a darkened space where Cave’s objects are picked up with white-gloved hands and investigated. “There is a real archive of sorts, the Performing Arts Centre in Melbourne houses collections that relate to prominent Australian performers, including Nick.” Cave donated many personal items to it over the years including memorabilia from his career. Iain and Jane also asked the curator there to appear in the film, as well as bringing personal items from Nicks’ mother with her. “The real collection is exactly as you’d expect: a modern institution, glass and steel, temperature controlled, big sliding drawers and white gloves. We wanted to create a dramatic space, a place that spoke of the idea of memory, full of dusty corners and distortions. Within our artificial space Nick is speaking to a real curator about real artefacts from his past.”

Whether encounting the ghosts of his creative past or the vibrating energy of the present moment, Nick never comes across as a petrified artefact of his own past. Iain and Jane don’t resurect a rock legend, but restage an environment that helps us see the real, living artist at work.

Credits

Text Sophia Satchell Baeza

Film still from 20,000 Days On Earth