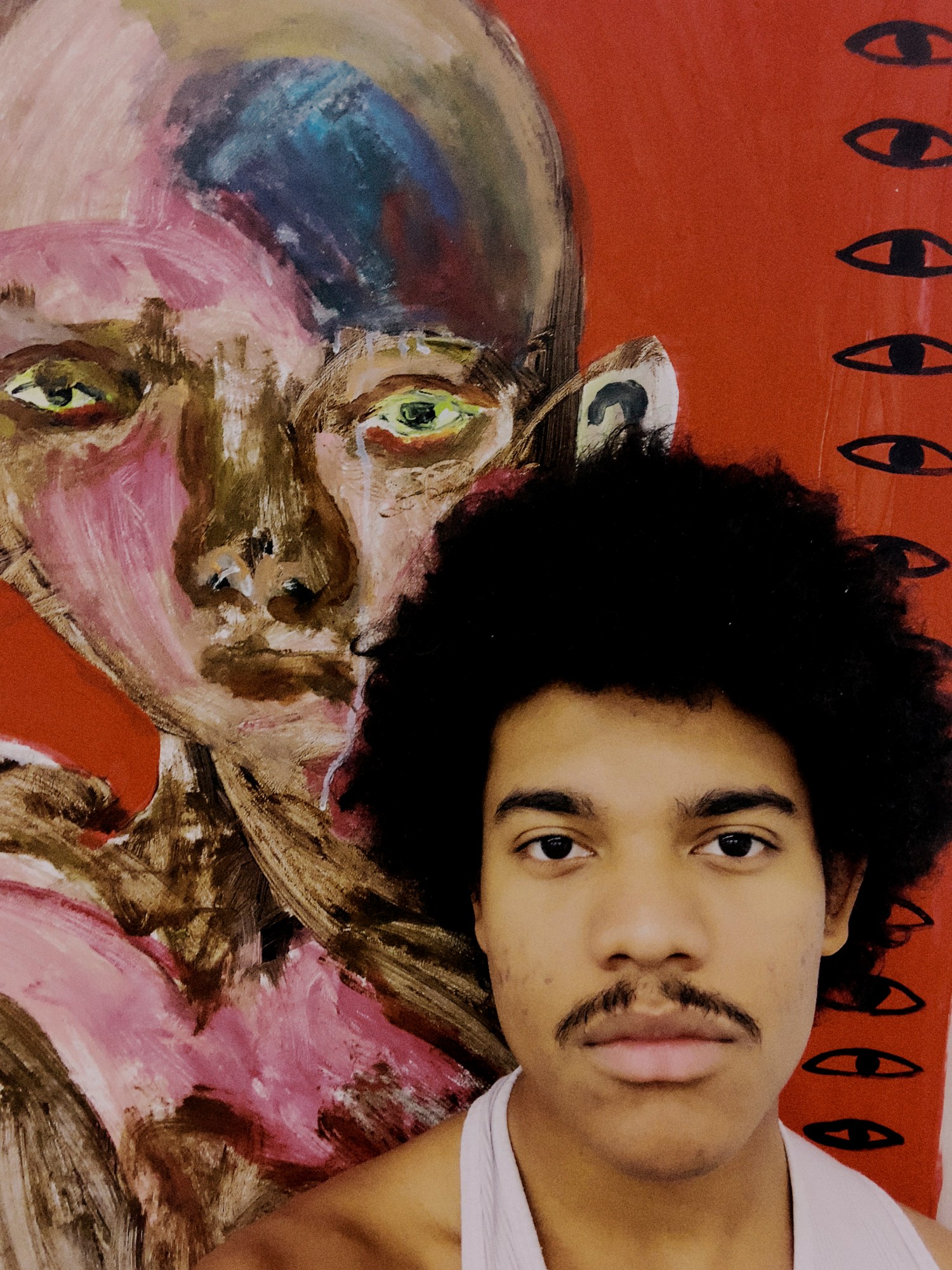

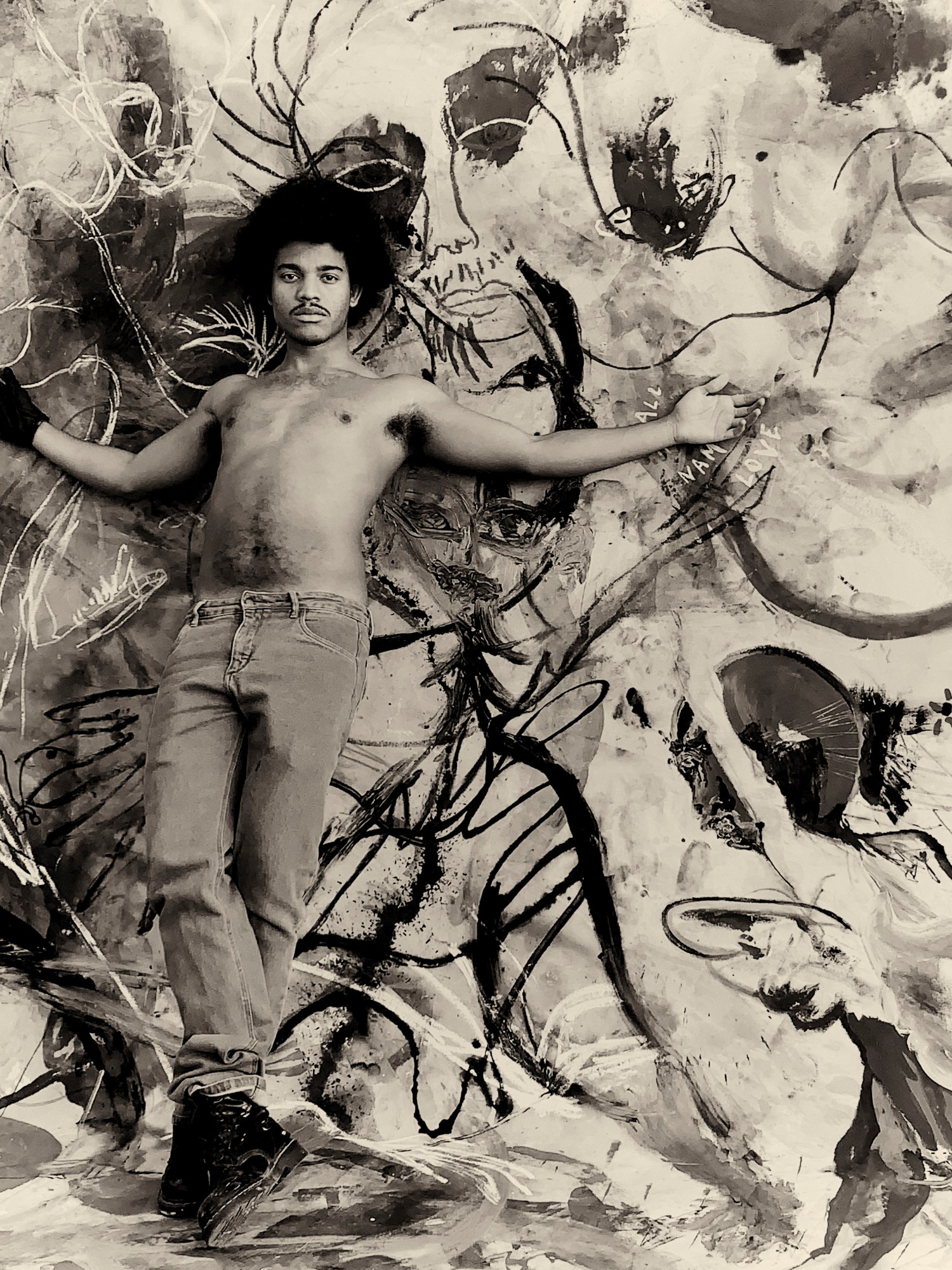

22-year-old artist Samuel de Saboia puts everything into his vast multimedia paintings. From his debut solo show, Beautiful Wounds, that dealt with the deaths of five of his friends — three of them in the space of six months — to his new show in Zurich, A Bird Called Innocence — “an ode to Blackness, joy, music and grief” — his work is wrought with joy and pain.

Samuel was born and raised in Recife, a city of four-million on the coast of north-east Brazil with a complicated past. Founded as the Americas’ first slave port, he grew up “hyper-aware” of the shadow cast over his home by centuries of slavery and colonialism. “Brazil is a country with one of the biggest Black and indigenous populations in the world, and a cruel history towards our kind,” he says. “I’m the result of many generations of other dreamers, of people that, even when life is most absurd, keep faith.” As a city, Recife is “a gem”, and so hot “you’ll never need a towel after showering”. “There’s a shit ton of bars and music all around, but there’s also a lot of violence,” he adds. “You cannot be too soft in Recife, at least not without a crew.”

His first loss — “E, the sweetest kid, shot 15 times in the back aged 17” — beckoned a series of untimely deaths that have since become inextricably linked to the art Samuel creates. “From that point on, many friends suffered the same fate, so each day I celebrate life for them, letting their memories be seen and heard through my work.” His paintings are a dialogue between grief and the sense of community that trauma can bring. As a young queer man, this community is vital.

At a dark moment in Brazil’s history, with Jair Bolsonaro’s government putting LGBT+ Brazilians in increased danger, simply existing and thriving in Brazil feels like an act of defiance. “As Toni Cade Bambara once said, ‘the role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible’, and what can be more revolutionary than to live, strive and change a world that wants you dead?” With his new show in Zurich, and his artwork adorning the most recent cover of Vogue Brasil, Samuel stands at the foot of a new chapter in his life and career. “I just hope that I’m not doing this in vain,” he says, “and that somewhere, someone is listening and getting exactly what they need to fuel their own dreams.”

Tell us a little bit about your first interaction with art and what it felt like.

I had an amazing aunt that was a hyper-realistic oil painter specialising in flowers. She made a white arum lily on a black silk canvas as a gift to my parents when I was born. I grew up watching her in her studio. She passed away from a brain tumour, caused mainly by the inhalation of the chemicals from paints. She taught me one of the most gruesome lessons about art, it becomes your everything and can also take everything. Since she passed, when I was 10, I’ve been painting non-stop. Sometimes I like to imagine how she would react to some of my works and it makes me really happy.

The artworks you create, across different mediums, are very large and feel very organic. How do you conceive of and create these expansive pieces?

I’ve had shows where I’ve spent three days inside of the studio and only left to take a shower. I’ve lived inside of a studio so I wouldn’t even have a chance to run away from my work. Sometimes I will return to my hometown and visit my parents so I can paint in my old bedroom. It all depends on what I’m trying to achieve. The common points are, there will always be love, light, a view and a quiet zone. It’s very rare for me to have people around when I’m creating – it takes some introspection to really hear my mind and heart and then put it to work. Most of the time I feel both as a creator and a vessel. When I was younger I would get into trances while painting, spend days without eating and just sleeping when completely necessary. This still happens if I’m too focused on a certain piece. Every artwork is a combination of external life and digging deeper into myself.

You were 20 years old when you exhibited your first show outside of Brazil — Beautiful Wounds at Ghost Gallery in New York — the collection that dealt with the deaths of five of your friends in Brazil. How did you confront such trauma in your work and turn into something you wouldn’t be repelled by?

That was my first solo show outside of Brazil and it was truly moving. I saved so much money to make it possible. God really helped me on this one. Every work had its portion of joy and grief, beauty and horror, it was a non-exploitive view of what it means to grow up in Brazil, seeing your dear ones be taken away.

So much death and beauty explodes from the same place in Brazil. We live in a 24-hour news cycle of dreadful stories, so to exist and achieve such things is a revolutionary act. The pieces remember the pain, but also every beautiful, lovable and simple aspect of my friends’ lives. Our memories, inside jokes, the infinite parties… each of those moments passed right through me and I can feel their strength and presence everywhere. Everyone brought flowers to the opening to put in front of their favourite artwork. It ended as a goodbye ceremony to some of my loved ones. For this show I wanted something that would allow my friends to be remembered as they were, and they were truly beautiful.

Your work deals with the complications of Brazilian identity. During such a tense era in Brazil’s history under Bolsonaro, what has been the most stark change to the country you grew up in? Have you incorporated this into your art?

Brazil was always known for its sense of community but the Bolsonaro regimen made people even more aware of it. It’s pretty much the only good thing that came as a result of his regimen. Every dictatorial moment of Brazil’s government had its own counterpart of cultural movement. Brazilians know very well how to use art to react; how to create art as a response to violence and despair and as a way to give hope for a better reality than the current one. At the same time, it is extremely exhausting to live in a country that glorifies death and minimises queer, Black and Indigenous lives. The way I’ve found to incorporate this specific moment is in making my pieces storytelling devices, so that names, faces, memories and lives will not be forgotten.

You’ve been quarantining in Switzerland in anticipation of your new show, how are you adjusting to life there?

It has been quite intense; a new country, a new language, new ways of behaviour. Zurich is quite bland but there’s beautiful people (shout out to the Zurich Art Bitches) and this nice hidden way of living. When quarantine ended I would finish a painting in the middle of the afternoon and then walk to the nearest river or lake. Sometimes I would end the day walking along the river near home with a bottle of prosecco. Sometimes I would hand my bag and my pants to a friend, jump from the bridge and swim to our spot instead of walking. As crazy as it sounds I would never imagine doing that somewhere else. I cannot ignore the racist tendencies either, but so far I’ve seen more goodness than evil.

The show itself — A Bird Called Innocence — is “an ode to blackness, joy, music and grief” as well as an experiment with “the detachments of turning into a young adult” — is this something you’re grappling with as a 22-year-old?

Ain’t we all? Maybe if I had seen myself in any ‘coming-of-age’ movies or series. I’m not Blair Waldorf or that other white chick from Ladybird. I’m not on a Call Me by Your Name type beat, either. I’m a Queer Afro-Indigenous Visual and Multimedia Artist from a Third World country ruled by a wannabe dictator. I was born in a place that since day one tried to set me up to fail, but where there’s hope, there’s beauty, and to not only achieve but inspire is a tremendous blessing. There are days that I’m not sure if will be able to make it, but then I remember each story, name, smile, hug, cry, shout, each breath of pure bliss and also the moments of total despair that me and mine had gone through and all this catharsis of these feelings ignites something deep inside me. It’s the fire, the love, the old wisdom but mostly it’s hope.

Hope that I’m not doing this in vain and that in the Sertão of Brazil or in a slum in Mumbai, or somewhere deep in Amazonia there’s someone that is listening and getting exactly what they need to fuel their own dreams so they are able to shape their own reality. We live a global struggle so we might as well be part of a global revolution. My biggest flex is to end each day alive and healthy. The rest is God’s doing. So, as long as I can, I’m going to challenge the views of what the world is and how it should be and, in the process of becoming my final version, I hope to also set the path to an infinite number of dreamers.

‘A Bird Called Innocence’ by Samuel de Saboia runs until 15 August at Kogan Amaro in Zurich, Switzerland.

Credits

All images courtesy Samuel de Saboia